The author of Ghost Of on the importance of constraint, the page as a field, and facilitating findings among her students

May 6, 2020

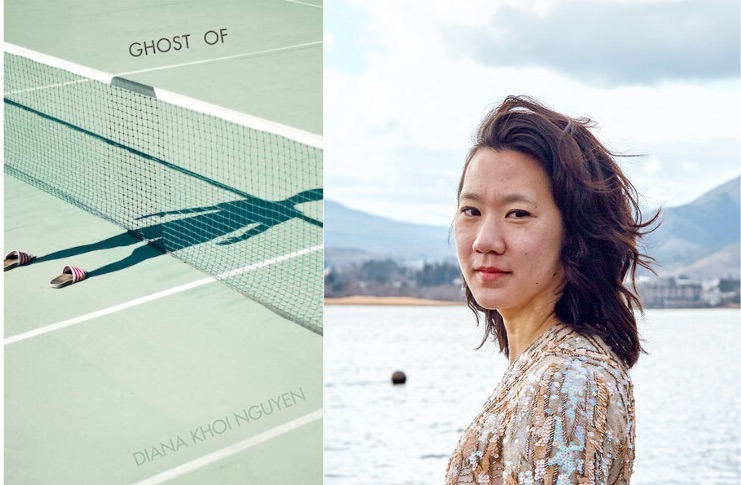

Diana Khoi Nguyen’s debut collection Ghost Of, published in 2018, contains a series of family photographs that were mutilated by the poet’s brother Oliver before his suicide—he cut himself out from the portraits, leaving an empty hollowing absence behind. These photographs hung in Nguyen’s house as an unaddressed scene before and after the suicide, forcing Nguyen to, one day, “fill in the space” both out of grief and need. “I am working with grief, death, and family trauma to a cryptic degree” Nguyen laments, “My grief wasn’t a form I went on looking for. It became an artifact that became available to me.” What comes across as artifacts are ghosts created visually and textually. They hold a physical and figurative presence. They are the existence in a space filled of a space forever absent.

Ghost Of explores Nguyen’s personal grief after losing her younger brother, Oliver, to suicide, and also explores the Vietnam war, seeking refuge and existing in the American landscape, and the intergenerational trauma that leaves one without a singular narrative of one’s own consequence. Published by Omnidawn, Ghost Of was a finalist for 2018 National Book Award in Poetry. The forms, the images, the language, the techniques, even the conventional empty spaces on a page which we take for granted, all contribute to the poems Nguyen writes. She explores different ways of navigating loss. Why should we mourn? Nguyen writes in the final lines of her poem “The Exodus,” Isn’t this the history we want/one in which we survive? and when I glance just beneath the title, I read “Saigon to Los Angeles, 1975-2015,” and I lament on the violence that takes place in the aftermath of violence, the one that is unseen, the one that survives as well, the one that takes form through other ways, through photographic cut-outs, through suicide, through the book.

When I interviewed Diana Khoi Nguyen in 2019, we talked about not only poetry but the world of it, of how diversity and inclusion can be practiced in white institutions, and how dialogue can be attributed to every conditioned being to acknowledge their conditioning enough to move forward in its absolute awareness. Nguyen and I ended our conversation on the same note that we started on—our work is not just for ourselves, it is also for the Othered.

—Ayesha Raees

Ayesha Raees: What does form mean to you?

Diana Khoi Nguyen: I believe in constraint. As both a practicing writer and as an educator, I believe constraint can yield something that might not have been said otherwise. Something about having to work within confines allows for a different kind of language, subject, or something more unexpected to emerge.

At the same time, though, I don’t think in constraint all the time, and neither do I always write in it. Through the forms in Ghost Of, especially in the poems “Triptych” and “Gyotaku,” I am working with grief, death, and family trauma to a cryptic degree. My grieving wasn’t a form I went on looking for. It became an artifact that became available to me. This artifact had a really terrible power, yet I wanted it. One night, I just didn’t know what to do. I sat staring at my family’s photographs, and I decided that rather than just sit there and feel awful, I should try to fill in the space left behind by Oliver.

AR: Apart from your hybrid visual poems, I want to expand on the non-visual yet still unconventional form you chose to write in. Your poems “A Bird in Chile, and Elsewhere” and “The Birdhouse in the Jungle” stand out in regards of enjambements and caesuras. Your poem “An Empty House is a Debt” is a list. In light of such poems, how do you approach questions of form and context? What comes first to you?

DKN: In general, I get bored pretty easily, and that’s my starting point. I begin every poem I write quite organically. And I don’t edit the poem afterwards to a large degree—it is how you see it as a reader. For me, it has a lot to do with intuition—move that line over there, decide to keep this one here. I write in such a short amount of time but when I am writing each piece, I write it very slowly. I write one line and then I sit there for a while. I think about it. Then I write the next line, and then go back to the first line, and so on.

AR: It’s almost like editing on the spot.

DKN: Quite so! Later on, I don’t actually have to revise very much because I’ve gone over the “field,” the page, so many times. There are, of course, little bits of edits here and there, especially with pieces I just can’t figure out what to do with, and then I will return to them months later. This is what my process has evolved into now. The poem comes out really slowly. It’s almost like hand-embroidered work. You put each bead down and then you have to make sure that the next bead is going in the correct place. If you mess up, you have to go back. You have to undo everything, you have to redo that first bead or that first stitch.

I used the word “field” for the page because I really love that kind of open field that words and lines can move across. It was intentional for me to include and incorporate multiple forms in the book. Not only because I write in different forms but I didn’t want the book to be just one thing. I wanted the book to hold different kinds of facets. I wanted different kinds of visuals. In an open “field,” I wanted different kinds of lineation to my contextual voice.

AR: The book is not “One Thing” and this shows in its arrangement as well. You divided the book into three sections, opening with a visual hybrid poem, a silhouette of your brother with his name written in the background, followed by—only in comparison—a more traditional poem “A Bird in Chile, and Elsewhere.” How did you end up making the choice to open the collection with these two vastly different poems, as well as to have three sections in Ghost Of?

DKN: When I was trying to order the book, I didn’t want something linear. I organized the poems in piles. The “Triptych[s]” were in one pile. The “Gyotaku[s]” were in another pile. There was a series which I mostly ended up cutting out from the book. Most of the poems belonged to different kinds of categories. They were about my parents or Oliver or myself and so on.

As I have worked with textiles before, a lot of my process is fetched in respect to that world. I weave a lot, and just like with weaving, I took the different poetic strands and I began to put them together. It was really fun to pick a strand to begin with. I wanted to start at the end, which means I wanted to start with my brother’s death.

That’s how “A Bird in Chile, and Elsewhere” functions. I love the idea of a little proem that begins and sets the tone of the book, like that one single note played before the rest of the orchestra. “A Bird in Chile, and Elsewhere” has that soundlessness which eases from what is before it: the silhouette poem which, ultimately, represents the Ghost.

Even though the book is dedicated to both of my siblings, I wanted to give a special ode to the presence of the Ghost. Of course he is there throughout the book, but to also have his presence and his absence at once on that single page was my intention. Oliver’s name printed in gray across the whole page almost reflects those old library books which, when you open their covers, have a watermark of the publisher. I wanted him to lead the reader into what the book contains. I liked thinking about him as part of a fiber of both the page as well as, ultimately, the book.

I think about weaving where the material is natural and organic, where the material isn’t just an object but also a subject. That’s the nature of how I began and after that, I layered my writing in pieces. I wanted things to build slowly and evenly.

The three sections were really deliberate—there were three siblings. It’s not like the sections are about each of us siblings, but I like this trinity that the number three gives me. It’s a prime number. It’s uneven. Yet, also stable. It makes me think about a stool, about how it doesn’t have two legs. A stool with two legs is more likely to fall over than a stool with three legs. I like to think of the number three as an essential number of stability. The family is now unstable because one of the children is gone.

In respect to contests, book prizes, and just generally preparing a manuscript: one is advised to put the best poems toward the beginning of not just the book but in front of every section. I wanted every part of the book to be engaging and this is why the book is so short. It has been around eight years since my MFA, therefore, I have had many, many, many, many years of poems. I pared everything down to allow for the pieces that I wanted to be in that book to fully have their moment. I’ve read so many books that are wonderful but they’re 100 pages long. I don’t remember the 37th poem but I do remember the last poem or the first poem.

The poem “Ghost Of” feels like a kind of a dizzying climax. Even though it is an end, it is also a present, yet so much has happened in between in terms of the past, my parents’ past, and all the possibilities of an alternate present where my brother believingly exists now, which is also a nowhere. I wanted to weave all of that together.

AR: Not only your writing but also the way you reflect on your process is so intriguingly systematic. It seems to fetch from a strong intentionality to write in two sets of dedicated time: 15 days in the summer and 15 days in the winter. I wonder how the winter and the summer seasons influence your writing? Is the landscape or environment in which you have chosen to spent those 15 days also the same every season? What other aspects influence your process?

DKN: I write in the summer and winter because that is the only time I am not teaching and I am free. In December I’m usually at home. December is especially difficult because that’s the month that my brother committed suicide, and it’s important for me to be in a safe and familiar space which is at home, surrounded by people I care about. I don’t feel like the season affects my writing as much as the significance of time. My brother’s death anniversary leaves me fragile in that moment.

In the summer, though, because of the temperature, I feel more playful. I think it’s hard to feel playful when you’re cold, but even though there is a kind of playfulness in the summer, my writing doesn’t change too much. What’s nice about the summer is that I’m often in a different place. One summer, I wrote in Taos, New Mexico and this past summer, I was around the Washington coast. Two Decembers ago, though, for the first time, I didn’t write from my usual home but from Vietnam. It was quite a different experience and I felt totally disoriented.

The thing that affects my writing practice the most is that I don’t write alone. I usually write with a few different friends who all live in different parts of the country. They’re also writing every day for 15 days. We check in with each other to make sure that we did it because if you’re just by yourself, you might not end up committing to your goal. It’s just nice to know that you’re not alone in this grueling writing marathon because it can be so hard to try to write a poem every day. What my community provides for me influences me significantly in my writing because I will start noticing how our work begins to correspond with each other—sometimes we would all write about birds or something. When you’re in sync with a person, simultaneous things emerge. You get to know each other’s work in a raw, vulnerable way and their writer-DNA starts corresponding with your writer-DNA. I don’t feel like I have adapted their style, but their voice and their obsessions are in my mind, and in an intense period of creating, you begin to draw from everything that’s in your mind.

The environment has stayed consistent as I’ve been doing it with the same group of writers. Every now and then, I’ll add a new person but this process is not for everybody. I have one friend from my MFA, she’s been doing it with me for six years. There’s something about the intensity of that period that produces interesting significant work. If you aim for 15 poems, you might end up with seven that can be used. That’s seven more than what you had before you started.

Ghost Of was written only in 30 days, in August and December 2016. The book was picked up the following year in March and then it came out a year later.

AR: As an educator in a college that is predominantly upper-class and white, do you practice any techniques that allow for an inclusive environment for those who are already feeling racially, or otherwise, Othered?

DKN: In my creative writing workshops, I bring in diverse readings, many different voices from many different places. When it comes to teaching, it’s not just about my aesthetic or even my agenda. I don’t want my students to try to figure out what I like and then cater to me. I had so many teachers in my MFA who just wanted me to write their kind of poems. I didn’t find it helpful. It took me three or so years after my MFA to break away from it. As an educator I just want people to find the thing that’s most exciting for them. I want to facilitate their findings.

I’m working now on a different model for a workshop. I don’t like the Iowa model. The Iowa model comes from a very specific white government military structure, which is of investigation. It comes from a CIA operative where the ‘writer’ is ‘gagged.’ They can’t speak while everybody around them talks and critiques. There’s just so many things wrong with this. I was chatting with another writer who teaches at Virginia Tech and she did a class where they workshopped different types of workshops. They came up with 20 different kinds of workshop models and in one of them you can only ask questions that are very specific to your writing. I love that. When each person is up for workshop, they choose the model that they want. It’s a consensual way of moving forward. The Iowa model isn’t always consensual. I think about these things actively in my classes at Randolph. It is a place where I feel I can really be me, where I can feel free to be inclusive and talk about inclusivity. I don’t want to partake or recreate the institutions I’ve been a part of as a student.

AR: Would you like to share any words of encouragement to both emerging writers as well as to students of color who are only exposed to a writing world that might not be nurturing them? What can they do in their current situations to help themselves as well as help others in a similar situation?

DKN: This is a hard question but I want to tackle it as coherently as possible. My main advice is to take as much space as possible. Be big. Be loud. Speak up. All the time. I understand that might not be for everybody. It’s hard to speak up, so do so as long as you are able to feel safe. Take up a lot of space. Be an advocate for all of the introverted voices regardless of color or other socio-economic factors. Being an advocate for those voices that are less heard in the program, a workspace, or in any other space goes further than anything because it’s not just about you, it’s about your environment. We’re all in this fight together. We must make it a mindful one.