“When I was initially describing this book I was like, ‘It’s about young women failing. Just failing, a lot, at life.’ That was my elevator pitch.”

December 19, 2018

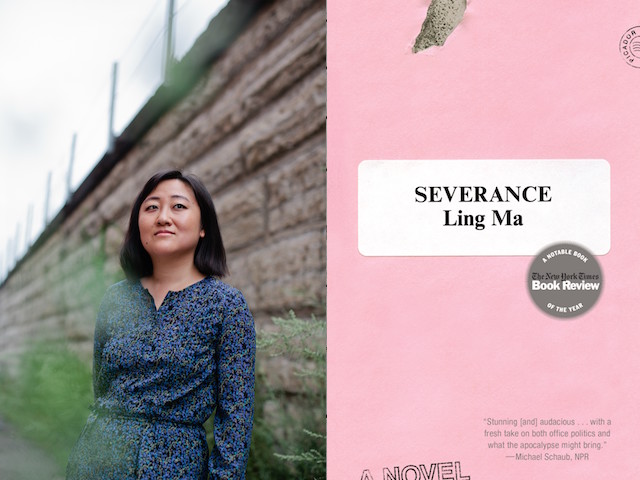

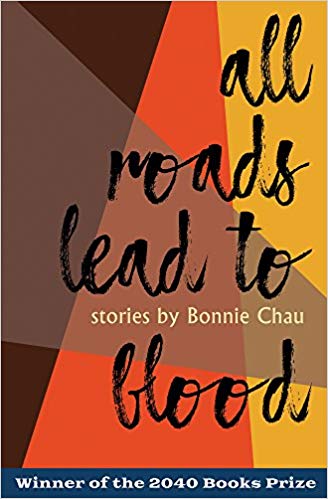

In All Roads Lead to Blood, Bonnie Chau’s debut short story collection, the relationship between our inner and outer selves—what is yours and what is mine—provides a through-line for the excavation of her women characters. “In order to see the shape of Stevie, start here, with the shapes of the guys,” begins the third story in the collection. What follows in “Stevie Versus The Negative Space” is a wry, intricate, and deadpan portrait of Stevie through the lens of her relationships, from Diego the sculptor to Dave the Golden Boy. As each partnership comes to an end a new shape of Stevie emerges. By cutting away the chaff we see that Stevie is all that remains.

In the sixteen stories that make up All Roads Lead to Blood we are buoyed along, not so much by what happens to the characters but by an accumulation of details surrounding loss, desire, and the difficulties of connection. When meeting a new partner for the first time, one narrator asks, “What is it like, to have someone say they want to see you? What is it like, to say this is not unusual for you, but this is unusual for me?” The women in Bonnie’s stories move through life attempting to define themselves against boyfriends, sisters, lovers, ghosts, and cultural expectations only to find that the most consistent thread is the self, in all of its unpredictability. Each story is punctuated by observations about intimacy that ring so true I often found myself shocked into recognition.

In the sixteen stories that make up All Roads Lead to Blood we are buoyed along, not so much by what happens to the characters but by an accumulation of details surrounding loss, desire, and the difficulties of connection. When meeting a new partner for the first time, one narrator asks, “What is it like, to have someone say they want to see you? What is it like, to say this is not unusual for you, but this is unusual for me?” The women in Bonnie’s stories move through life attempting to define themselves against boyfriends, sisters, lovers, ghosts, and cultural expectations only to find that the most consistent thread is the self, in all of its unpredictability. Each story is punctuated by observations about intimacy that ring so true I often found myself shocked into recognition.

Bonnie balances her characters’ interior lives with lush descriptions of the physical world. Sometimes the landscape turns surreal or threatens to overwhelm us, as when a dinner party in California turns into a crowded New York subway car, or when a jellyfish floats out of a kitchen faucet just as an ex reemerges onto the scene. More often than not the body is a site of intense, contradictory desires, packaged in Bonnie’s lyrical prose. Sex is described as, “a glossy photograph, a streak, translucent pectin covering a fruit-colored tart.”

Much has been written about Bonnie’s language and her distinctive sentences but it’s her ability to capture the interiority of her characters—to write men and women and the complex dynamics between them—that has me reflecting on her work long after I’ve finished reading it. As she writes in the collection: “Everything was about combinations of pairs, everything was about relationships between people and their feelings, everything was about sex, everything was about where you came from, and what you wore while coming.” We met this fall to discuss art, gardening, failure, and how it all comes together.

—Jen Lue

How and when do you write?

I write very irregularly, often when I have a good chunk of time. Usually that’s on a Saturday or very late at night. I write on my laptop, lying on my stomach, on my bed. It has to be at a time when I’m not really sleepy. That’s the only position and situation where I can get the writing that I want to do done. Revising and editing I do at the library next to my house.

Do you have a desk in your room?

I do have a desk in my room but it’s kind of a mess. I’m really disorganized. I have all of these piles of papers and books surrounding me. If I cleared it off and kept it clean, I could probably get writing done there. That’s why I’m on my bed, because I have to clear my bed every day. It maps onto a cleaner blank slate in my head. My desk is not a productive place for me at all.

You just came back from your first book tour promoting All Roads Lead to Blood both here and on the West Coast. Do you have a particular audience in mind when you write? Were you surprised by anyone you encountered on tour?

A lot of my short stories evolve out of diaristic writing. It’s me writing for myself. Once I’m past the initial drafting stage and I start working on the more administrative, publishing side of things, I start thinking, what’s going to be unclear? What’s going to need explication? I’m still not thinking about a specific demographic or audience. I think about that a bit more when I do readings.

I haven’t always written explicitly about being Asian American or struggling with Asian American identity. Once I started writing about that, which was very much connected with me being involved with Asian American writing communities like Kundiman and the Asian American Writers’ Workshop, then the awareness was definitely there. I hope that my audience engages with these issues and that there are Asian American readers who will find resonance in the things that I am writing about.

In an interview with The Offing you mentioned Marie Mutsuki Mockett’s essay about story structure and how fairy tales and old wives’ tales, all the stories we were told as kids, serve as maps for our idea of what story structure is. I was curious what kinds of stories your parents told you and what sorts of stories imprinted on you early on.

My parents definitely made sure that books and stories were always around. I went to the library with my parents and my sister all the time. We chose the books that we wanted to read and it was always a wide range. I read a lot of series. Five-Minute Mysteries, Encyclopedia Brown, The Baby-Sitters Club, Nancy Drew, Sweet Valley High. Christopher Pike. A lot of Roald Dahl.

I was never really into the classics. I wasn’t as interested in books like Little House on the Prairie. For a lot of the books I read, it wasn’t the plot that was interesting to me. I just liked being in another world and being enveloped in words and language and descriptions of places and people, in interactions and dialogue.

My dad is very much a storyteller. He would always tell us bedtime stories. He would pull things from out of his head. Really crazy, nonsensical things. My mom would just shake her head like, “There he goes.”

There’s so much interplay between male and female characters in this book, in the form of romantic relationships and missed connections. How do the characters come to you? Do you pull from real life?

I definitely pull from real life. In general, I’m for the abolishment of the genre distinctions between fiction and nonfiction.

All of the characters in the book are monstrous combinations of people I know, people I’ve known, my friends, my family, and me. My fiction is very nonfiction-y fiction. I’m interested in exploring relationships through larger tropes, like the tropes of little sister-big sister or parent-child.

Many of the stories are about transformation and turning into different things, of being multiple selves. To me, that’s very much related to what I’m doing when I’m storytelling and what I’m doing when I’m creating a character. Every individual character is made up of many different characters and that’s why it works.

Even though I’m pulling traits and actions and personalities from different people, I don’t think that that makes for an inconsistent character. You can never know all of the different people that are contained in one person.

Do you ever worry about people recognizing themselves in the stories?

Not in the initial stages of writing. Once it’s going to be published or when I get ready to do readings, I’ll think about it. I’ll wonder, “Is so-and-so going to be in the audience and might they think something about this?”

It actually happens fairly often that people will say, “Oh my god, that was me,” in relation to a specific character. Parts of them might be in there but they’ve also identified themselves in someone completely different and it’s shocking to me. I’m like, “Oh, you don’t even see yourself.” So often we can’t see ourselves.

The character in the story has also absorbed the tendencies of someone else. So I can be like, “No, that’s not you. That’s not really just you, at least.”

I think that segues pretty perfectly into something that I had noticed a lot as I was reading the book which is that many of the female protagonists are interested in seeing and being seen. It’s almost as though they want to be rendered legible or translated through their proximity to the sister relationship or the partner relationship. Is there something particular about the sentiment of the “eye” or the “I” or seeing that you’ve always been drawn to?

I think a lot of it has to do with being in these in-between spaces. Of speaking multiple languages and not really knowing where you fit in. Of being Asian and American and navigating what that means. Of being a person of color and dealing with the dichotomy of being both hyper-visible and also completely invisible.

There are certain traits that I feel really attached to. Being a little sister has always felt very defining for me. Then there are certain traits that have been assigned to me, that society and stereotypes have pushed onto me that I don’t measure up to or that end up making me feel very invisible. Visibility and invisibility is a very personal thing to me. It has something to do with feeling like I could try to be one person but that this was not my real person. I’m interested in incongruity in that way.

It’s interesting because in all of the sexual relationships in the book, not one of the characters seems to be looking for an “I love you.” It’s like being seen, that moment of recognition, is akin to love.

Maybe that’s too telling of my own personal love life. [Laughs.] I do think that a lot of the most intimate feelings of being with someone, whether that’s a family member or a friend or a loved one, are not found in these very explicit expressions. Individuals have such secret and private lives. Couples also. You never know what’s really going on in someone else’s relationship. I think that’s something that I try to explore. The small moments. One of the dedications of the book is to secret loves and loves not so secret. Maybe that’s it.

When I was initially describing this book I was like, “It’s about young women failing. Just failing, a lot, at life.” That was my elevator pitch. Then, over the last year, as I’ve been working with the collection more closely as a whole, looking at all the stories together and thinking about them as one coherent project I was like, “Wow, yeah, they are failing in many ways but a lot of it is also about failed love.” I think even in the face of what I would half-jokingly consider failed love, I want to find these moments where there is tenderness or intimacy or feelings of closeness, of being seen.

One thing I think about as a Chinese American writer is the tendency to self-Orientalize. Another thing that is equally hard to write about is proximity to whiteness or the reality of understanding and feeling drawn to elements of the dominant culture. As one character jokes in “Monstrosity,” “He would be the closest thing to a Chinese guy I had sex with…” Do you ever think about those concerns?

I definitely do think about that. In preparation for the book coming out, I had to Google myself. I used to write an opinion column when I was an undergrad at UCLA for their newspaper, the Daily Bruin. I just wrote whatever I wanted to write about and my first column was about Asian fetishism. That was very clearly something I was thinking about eighteen years ago. It’s one of the many entry points into more explicitly political writing that I’ve been thinking about in the last three years.

I find it interesting that we often think it’s not a legitimate experience. Sometimes there’s fetishism involved and sometimes not. The script is not always the script.

You were saying that a lot of your process is collagist, using cut-ups. Are you ever interested or jealous of other people’s creative processes? Is there any visual art that you’ve wanted to try?

I am always jealous of other people’s creative processes. Not as much writers but visual artists. I started out writing as much as I was doing painting and drawing. My parents are art lovers so I grew up going to a lot of museums and they would enroll me in art classes over the summer. That was always my favorite class, art class.

Being an English major was an easier, more acceptable thing to be than an art major. After grad school I wasn’t writing. I was doing ceramics pretty intensively for a couple of years. I still draw and paint a bit. That’s always been a very important and strange part of my life.

I love having a physical object and working with my hands to actively make the shape of things. A lot of my writing comes out of circling around, being preoccupied with certain images from memory. I use a lot of images. I wonder sometimes what my work would be like if I had decided to concentrate more heavily on another medium. There’s also an openness to abstraction in visual art that’s not as evident in writing. Often when you work with abstraction in writing you get told, “You’re doing something experimental” or “You’re doing something that’s different.” That’s not a problem but it feels a bit lonely sometimes.

I’ve gone to a few dance performances here in New York and those experiences have always been very overwhelming to me. Definitely another point of envy. For writing, all I need is a brain. My brain connected in some way to my hands and to a computer screen. To see these different ways of making art out of your body seems so powerful to me.

I think you put a lot of that physicality into the writing.

I hope so. It’s something that’s interesting to me.

A lot of these stories were written between 2011 and 2016. What’s your relationship to the collection now?

The collection should have a subheading “2011-2016” on it so I can mark it as a period like artists have their “Blue Period.” [Laughs.] Having a book out in print, getting it published, it takes so long. It’s not as dramatic as a past life but it does feel like a part of my life that’s over.

I like that there’s conversation around it and that I can think about the writing with some distance to it, in a more objective way. Along with that distance, I can see more clearly that I was writing about failed love. Also, that I was really preoccupied with characters turning into animals and beasts. A lot of clawing and teeth and trying to get into the soil of things.

It’s a new experience to think of my work in that way, to be able to draw a line around this bunch of things. In some ways it’s helpful because I was so afraid of thinking of it as one project, as one collection. Do these even go together? Are they a collection? To be removed from it a little bit and to see the threads that move throughout, to see the themes and motifs and preoccupations, has been an education into how I work as a writer.

I read a number of reviews that mentioned your language and your sentences in particular. I also read that at Columbia you got a literary translation degree. Do you think that studying translation has had an effect on the way you look at language? Are there any writers whose sentences you really admire?

One thing I think about a lot is the type of English I’m writing in. I translate from French into English and from Chinese into English. Which English are you translating into?

There’s this idea that you translate into some sort of neutral, clean, universal, literary English but does that even exist? It doesn’t really. You can see that very clearly when you read a translation of something that was translated a hundred years ago into an English that feels like it was contemporary to a hundred years ago. How do you translate into an English that is open and allows for other languages or other types of access to language? That’s a more macro, general thing.

On the sentence level, I’m aware of how there are millions of nuances and connotations depending on who is reading and what your reference points are to every word. I already take a lot of pleasure in choosing language.

Do you feel like you read differently, when you’re reading something in a different language for pleasure versus when you’re reading it for translation?

I can barely read Chinese so I can’t read it for pleasure. The French books that I’ve started working on or done bits of translation from, I will sometimes read parts of them just to read. But I haven’t done that in awhile. I’ve been trying to focus on Chinese and that’s been the more interesting project for me, for the last few years.

You’re making it legible for yourself as you’re translating.

That really is the project. I just wrote an essay, my first-ever essay about translation. It’s about what it’s like to think of the end goal of translation as not necessarily being publication but that there are so many other reasons to translate literature.

We talked earlier about genre categories. You’ve been diving into essays recently. How does that feel?

It’s been hard. I’ve written one essay so far and I’m trying to start the next one. Over the years I’ve gotten so used to the permissiveness of fiction, of fictionalizing. That’s still my instinct when I sit down in front of a Google doc. To write something that feels very much like a nonfiction essay but at any moment being able to add in a detail that is completely made-up, to fill out the sentence or the image or the scene or the paragraph.

I think one of my gripes with nonfiction essays is feeling like you have to have learned your lesson by the end. I never learn my lesson. But I think that it’s not actually the case that you have to have learned your lesson, right? That’s where the word “essay” comes from, right? It’s the project of trying to figure out the lesson while you’re writing it. I’m still trying to wrap my head around what kind of essay or nonfiction I want to write or will end up writing. It feels a little precarious to me but I think that’s fine.

In your fiction you use a lot of vignettes. Is the essay written that way too?

I start by writing a pile of paragraphs and then rearranging them and seeing if some sort of alchemy works. I try to see if I can see something new or see a shape that might be emerging. Or see a way to make a shape. That’s how I write my stories too. In what way can I rearrange all of these different scenes or memories or experiences that are relevant to one topic and make it a story? That’s what I mean by learning a lesson while you’re writing it. The idea of a lesson and a story are related to me.

Do you ever do research for the fiction or the nonfiction?

For this book, I looked up the names of plants, various flora and fauna, but I’m not sure if that’s made it into the stories. I looked at maps, street names. A lot of the landscapes are from my own experience and are true to my childhood but I still have to look at maps to make sure. In the essay I mention other writing on translation.

That flora and fauna comment reminds me that you’ve mentioned gardening in the past. Do you garden?

My parents are pretty big gardeners so I grew up spending time in their garden, with weeding as a chore. I’ve always liked being out in natural environments. I kept plants in L.A. but I think in moving to New York, it was just so different. I’d get depressed in the middle of winter. I live really close to Prospect Park and I would spend a lot of time in the Botanic Garden. Considering my space and apartment constraints, I have a lot of plants. I have something like seventy plants in my bedroom. That’s why my desk has so many piles. There’s just no surface area.

In front of my apartment building, we have two sides of dirt and the possibility of plants. One of my roommates and I have been trying to transform it a bit. Last fall we planted 200 bulbs. We brought-in shrubs. We planted a cherry tree and a plum tree. There’s a lot of trash. It’s a battleground, for sure. It feels like it’s an important part of my life in the way that ceramics was. It’s all somehow related to my writing and what my concerns are.

What kinds of things have you been thinking about lately?

I’m working on a novel right now, supposedly. I don’t know what state it’s in. I’m still very much wanting to write a horror novel. It’s related to my interest in writing about and from the body. It’s a bit amorphous in my head right now but it’s a primary topic. I like thinking about horror and horror movies. I watch a couple a year at most, but I’ve always watched them on-and-off. I like B-horror movie creature stuff. ‘80s and ‘90s stuff. Did you ever watch The Babadook? That kind of thing. I’m very excited to watch Suspiria. I love Dario Argento. Same with reading horror literature. Daphne du Maurier, I love.

I don’t really know how to work with it but I’ve wanted to write something inspired by Christopher Pike novels for a long time. He wrote a trilogy about high school parties. The Party. The Graduation Party. That’s floating around in the back of my head too. Also the thriller and the erotic thriller. I have this idea that it’s all going to coalesce into some grand masterpiece but I have no idea how I’ll pull it together. We’ll see. I wish I were a connoisseur of horror. Then I would really be the person I wanted to be.