“For Korean women writers, for whatever kind of poetry they want to write, I think this country has excellent soil for growing in any direction you want.”

October 21, 2020

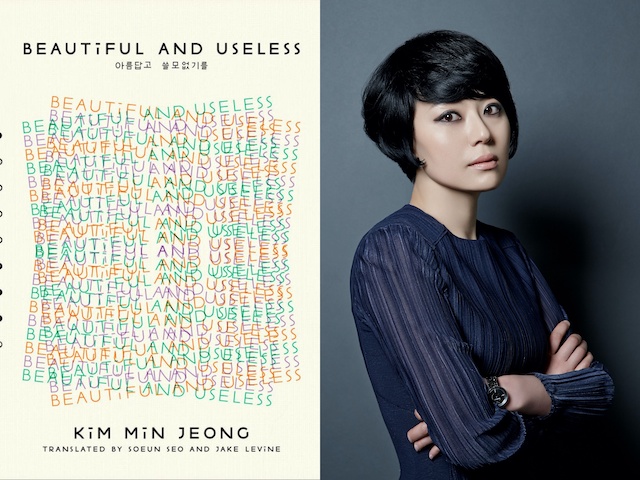

In preparation for the release of her first book in English translation, Beautiful and Useless (Black Ocean Press), the translators Jake Levine and Soeun Seo sat down with Kim Min Jeong and the poet Park Joon to discuss the history and current state of Korean literature, the development of Min Jeong’s poetic thinking and education, and how she imagines her work will be received in English speaking countries.

Jake Levine: You are known as a founding figure of the Miraepa school, a group of poets who changed poetry when they debuted in the early 2000s. Since then you’ve developed your style quite a lot and in different ways. Maybe you can describe how literature has developed and changed since that time.

Kim Min Jeong: Right, I mean Miraepa was just a term and it has been well over a decade already since we started using it. In the early 2000s the poetry world was really conservative, and the young literary circles felt that time was ripe for a movement. It was a matter of course that poets were passively selected by the publishing houses Moonji and Changbi. But in the five years leading up to 2004, from the time all of us debuted until 2005, we had this attitude, “If these important places don’t come out with our work, who cares? Individuality is our top priority.” So we started our own small presses to publish our books.

But poets weren’t really tied under the banner of whatever “Miraepa” [or “New Wave”] was. Rather, all these poets that brought their own new individual energies were thrown together. I was in the first generation of Miraepa, Park Joon was grouped into the second generation. Our poetry is distinctively different. And the new kids keep coming. So, it would be a stretch to say that Miraepa shares any characteristics. It’s just a way of describing the wave of fresh air that blasted through Korean literature and Korean poetry circles.

JL: Right, society changes, culture changes, there are new movements. With your generation, what were the broader changes in culture that led to Miraepa?

KMJ: Look, after the democracy movement, we didn’t know how to express ourselves. We got democracy, but we didn’t know how to express it artistically or how to enjoy it yet. It took a lot of time for us to figure out how to express our voices through art. This is when everything started pouring out. But we had to give up so many things—like the gravity of what we do, what it means to be a poet. When we freed ourselves from these questions, our individuality could be celebrated. We had to embrace the beauty of each piece, each fragment, and so it was time to accept this diversity in our culture. That was around 2004 or 2005?

Soeun Seo: And what about now?

KMJ: Now those fragments have become more fragmented. Fragments fragmenting and fragmenting and fragmenting… Back then, styles of poetry were like the solar system. Earth in the middle, planets orbiting around it, the big planets set the balance. Now, all the stars in space shine every which way.

SS: I have a question about a sense of entitlement in poetry. Often, these poems define themselves as poems simply by being solemn, as if deep seriousness is what makes poetry. Your poetry has a lot of puns, lots of colorful language that feels quite casual, so what kind of influence or impact do you think this has on readers?

KMJ: I don’t think about influence or impact at all. I don’t have a sense of entitlement. For instance, I didn’t study. I didn’t do something like a Ph.D. I didn’t learn inside the formal system. I gave all that up. So instead of all that, the accolades, the tenure, the academia, I had the freedom to say “Screw that stuff, I’ll do what I want.”

I mean, I didn’t want to educate people, show what I know, I didn’t care about being read. I wanted to express what I liked, things that turn me on. I thought about what makes me the happiest, when I’m having the most fun. I just focus on myself. I never said to readers, “Hey, look at my work!” I mean, who cares if anyone reads this shit.

JL: But you know, in your work, the puns… onomatopoeia, these things are impossible to translate…

KMJ: I mean, you guys did it.

SS: It was sooo hard.

JL: There are so many puns….

KMJ: If you have translation in mind, you wouldn’t write my kind of poetry. You probably think if you can understand universal emotions, then it’s the same for all the languages. But it isn’t like that. I mean I don’t tap on a calculator, I’m no good at being calculating, so what am I good at? I like puns. I like exploring the dictionary. I just focused on enjoying myself.

JL: But even though you didn’t study, you’re an editor. You’ve read a lot of books, probably more than most professors.What is the difference between the role you play as an editor and as a poet?

KMJ: I haven’t really read that many books other than poetry books. I’ve read lots of poetry books and tons of manuscripts of poems before they’re books. That’s probably been my education. You can see that in my poetry. Of course, I have a responsibility when I’m writing a book as a poet, but more than that, as an editor at a major publishing house, I’ve studied how to make poetry books, what attitude I should have, this responsibility for shaping Korean literature.

JL: In America it’s not that uncommon for poets to also be editors at presses. You and Park Joon are both editors. Is that common in South Korea?

KMJ: It’s uncommon. Usually poets become professors. Well, while I’m working on someone else’s book, it’s not easy for me to write.

SS: About that, how do you balance between your poet-self and your editor-self, and what is different?

KMJ: I think my editor-self is much stronger, far more confident and flexible. The poet me is shy. When I talk about my poetry I get startled and hesitant. But as an editor, say, I made Park Joon’s book, right? When I talk about Joon, I froth at the mouth with excitement.

If it was between making others’ books or writing poetry, I would always choose to make other peoples’ books. But I’m a special case. I love it when other people thrive and I like work that is very different from mine. Like many dishes on a dinner table, I think a diverse Korean literature is a healthy Korean literature.

JL: You’ve published the famous poet Kim Hyesoon.

KMJ: Yes, but not her poetry. Essays she wrote about poetry.

JL: Are there any poets like Kim Hyesoon that have influenced you?

KMJ: For me it was Choi Seung-ja. Even though Kim Hyesoon and Choi Seung-ja are basically the same age, their work is really different. Choi Seung-ja is a poet who writes with all of her body, and of course Kim Hyesoon also writes with her body, but she writes with her mind too. Choi Seung-ja writes first with the fire of her body before she starts to calculate in her mind. Kim Hyesoon’s poetry is obviously well crafted, structured. Choi Seung-ja’s poetry lets loose completely. It’s uncontrolled, unmediated. I like that heat. Originally, I wanted to write novels.

JL: Why novels?

KMJ: I never once thought about poetry. The thing I hated most in the world was the poetry I learned in textbooks. I didn’t understand why people liked Kim Sowol. Yun Dong-ju was annoying. But I liked the novelist Oh Jung-hee. When I was in high-school I read Oh Jung-hee’s novels, and the children that appeared in them, the sly, clever girls, I liked them a lot. I wanted to write something like that. I even went to Joongang University because Oh Jung-hee went there.

So I got to college, but I’m impatient, you know, like how I talk so fast. You have to sit there for a long time to write a novel and I just couldn’t do it. And then I started reading poetry. I started in college and it was so much fun. But nature poetry, I really hated that. I don’t know anything about nature. At that time the university atmosphere was like, well, there were no women professors. And there still aren’t!

JL: In Incheon?

KMJ: No, Joongang is in Seoul. It’s the most conservative university in Korea. I took Seo Jeong-ju’s class. The only thing you could write about was nature. And then I saw Choi Seung-ja’s poems, and I thought, shit, you can write like this? You can swear in poems? So, I quit. And when I say I quit, I mean if you didn’t write poems the way the teacher wanted you to, then you wouldn’t pass your class. They said I’ll never debut or get published. So I said screw it and did whatever the hell I wanted to do. I became a good writer because I learned to distinguish myself from the poets I didn’t like.

JL: Even today, like in contemporary poetry classes I took at Seoul National University, Lee Sang-bok and Kim Su-yong were taught, but we never studied Choi Seung-ja or Kim Hyesoon.

KMJ: Well I think universities’ creative writing and Korean literature departments are dominated by men. But what’s funny is that professors don’t want to bring in successful poets. You would think that if someone was talented and they graduated from Seoul National University, schools would be eager to take them on as professors. They just want someone obedient to the school, who studied things like classic literature. These kinds of people, even if you gave them a shot in their head, they still wouldn’t understand Kim Hyesoon’s poetry. However, Korean male poets, male literature scholars, they understand Choi Seung-ja, the wildness, the unmediated uncontrollable nature of her poetry. But they can’t understand Kim Hyesoon’s poetry.

J : Could you explain more on that?

KMJ: For a lot of Koreans reading is about analyzing. They can’t interpret the meaning. They don’t have the imagination. So they don’t even try. They can’t sell it in a textbook. But for you and for me reading is not just for interpretation or analysis. Before you analyze or interpret, you enjoy it. And in that enjoyment, you can create space to make interpretation beautiful, but for a lot of Korean men they just want to diagram. Like A equals B and if the formula doesn’t fit, they think, fuck this. So, they really don’t like Kim Hyesoon’s poetry.

SS: Earlier we discussed how many women writers aren’t taught at school, but for you, what do you teach and how do you teach poetry?

KMJ: I think women poets teach really well but they don’t necessarily develop the curriculum for the school. The entitled, old Korean department professors make the curriculum. But now you have people like me, a lot of younger women writers who have debuted, entering universities and teaching freely whatever they want.

The thing I tell students at our university [Keimyung University] is to really try to be different. I teach them, when others say “Ah!” you say “Boo!” Reject them. That’s how you make literature lush. Even though [my students] know they can try new things, they don’t think they can do it, so they just try to be like everyone else. I tell them, “Is this what you think? Do only what you want to do!” You’ve got to get rid of all the bullshit. When you strip down, you can see the muscle, the fat, and that’s important. When you get rid of the bullshit you are beautiful.

JL: When you were writing Beautiful and Useless there was the Sewol ferry accident and also the protests against Park Geun-hye that led to her removal, conviction and eventual imprisonment. These things appear in the poems. How did you write about them?

KMJ: We had two presidents I wanted to bury while I was writing this book. Lee Myung-bak and Park Geun-hye. Really, I wanted to kill them. Why? I like that kind of one-dimensional response. When I was a student I didn’t like political poetry, protest poetry, the poetry of slogans, democracy blah-blah. It wasn’t for me. But when this book came out, so many significant events had happened, the things I experienced then, I just couldn’t hide them. So, I mocked those in power. I’m good at indirect sarcasm. I think like a kid, like “Lee Myung-bak is super bad. And he’s ugly as a rat.” When it comes to political or social content, I blurt out the obvious like a child.

For the Sewol Ferry incident, there was a general sense of helplessness, where I didn’t experience the deaths directly and those who did were silenced. There was this sense that people should shut up about it since they didn’t experience it firsthand, but I did speak up, just very carefully, like “I don’t know, but isn’t it like this?” For political things, I face them directly, but for sensitive stuff like Sewol, I feel like I have to express my sadness in a way that hides it. So I use metaphors and mockery. In my poetry, those moments are immature. Political wrongs are so childish. And the only way to call out a childish thing is to say it like a child.

JL: But there is a lot of depth in your poetry.

KMJ: Look, kids are the most difficult. Kids can imitate adults. But it’s hard for adults to become kids if they aren’t quick witted. To talk about political subjects, I’ve got to be like a kid. Because if you calculate too much, or think about things too hard, you get worse results because you can’t be honest. The political inclination and the poetic inclination are in direct confrontation.

I mean why do poets write? Because of guilt. A guilty conscience. When we’ve done something wrong, like when a poet in love is sorry and hurt, they’ll write a poem about it and start feeling even more vexed about it. That’s the poetic mind. But if a politician admits error or fault, that’s it, their political life is over. The point of departure for the politician and the poet is completely different. The poet always says sorry, I’ve done wrong, and the politician says look at me, I’m always right.

SS: I have a question about the use of the lunar calendar in your poetry. Why did you use the 24 seasonal divisions to split up Beautiful and Useless?

KMJ: When I was a girl I saw the seasons of the lunar calendar marked in red on solar calendars but I didn’t understand what the seasons were. I didn’t understand even after I turned forty. But one day on the “Start of Autumn” on the calendar, the wind really felt different, like autumn wind. Just the day before the wind was warm but after “Start of Autumn” it was actually cooler. I had an epiphany: Wow, I am alive. Alive like the seasons. So I began to look at the lunar calendar again. I feel the difference in each season. They’re proof that I am living. I really love the 24 seasons, so after writing this book I bought the version of the calendar for farmers that tells you what to plant for each season. Because for farmers the lunar calendar is super important.

SS: Did you plant anything?

KMJ: I grow roses. After I wrote this book I thought, what can I grow? So, I grow roses.

JL: In your poetry there are a lot of poems about relationships between men and women, funny situations or strange situations, why do you write about this subject so often?

KMJ: I feel awkward about things like passion. I think if you’re that into it there’s not much need to express it in poetry. I mean, I like funny situations, and even if you’re a couple madly in love, there are parts that just don’t fit. Like if you put a protractor to it, you could measure this much crack. And that’s where we can find balance and beauty. If you say “We are one!” and then you realize you’re not, that’s painful, it can be a big wound, but if you leave a crack open, a crack you can escape through, you can live with other people. In poetry, too, that distance makes people flexible and generous, and I think you need that especially in romantic relationships. Couples can be intimate as well as get into a lot of funny situations that aren’t necessarily about breaking up. They observe each other. Humor allows for forgiveness and understanding.

JL: Park Joon, I was wondering if you would be able to talk about what kind of role Min Jeong plays in the poetry world in South Korea.

Park Joon: Of course, there is no one like Min Jeong. Poets have this ideal, this idea, this self-pride when it comes to their work. And this is something they can’t really communicate. It can’t escape directly into the real world. So, when the work takes its published form, when it comes out as a book, this ideal, this idea becomes damaged. First the ideas are damaged when it becomes language, and then the text puts on the clothes of a book and gets damaged again. Out of all people, Min Jeong is the best at reducing this damage. You can’t completely get rid of the damage. How do you take ideas and express them all in language? And when you dress up the text in language, when it puts on the clothes of the book, that text becomes so different!

SS: What about Min Jeong as a poet?

PJ: Ha, it’s unfortunate she’s also a poet, right? Yeah, she is like Jekyll and Hyde? Earlier we talked about identity. The identity of the poet and the identity of the editor. For me, when I think of myself, my poet identity is stronger. When I work as an editor, I’m like any laborer. I go to my job and do my work. But Min Jeong is not like that. Her identity as an editor gnaws into her identity as a poet. It’s unfortunate. Unfortunate for her poetry. Because her identity as an editor takes priority.

The funny thing is, I think you can imitate most of the Miraepa poets’ poetry. Like as soon as it dropped, maybe people were imitating 80 percent of it. Like baseball batters, they took the posture like they can guess at 80 percent of the pitches, but you can’t get all 100 percent of it. Picking out, analyzing and imitating the metonyms, rhetoric, etc. The 10 to 20 percent of what is leftover after all the imitable style, that’s what make’s poetry poetry. This drives people mad.

KMJ: Yeah, you might think I’m full of it when I say this, but people can’t imitate me because I only use non-poetic language. In my first book of poetry the word I used most was “eyeballs.” The shape of the word “eyeballs” in hangeul makes your eyeballs greasy. I called this mochi I got from a bakery eyeballs because the white mochi has black bean paste in it. Someone told me they can’t write “eyeballs” in a poem because of me. Now eyeballs in poems feel like they’re moving.

I tried not to use words that other poets use often. So I ended up cramming in all kinds of words like cockroach, eyeballs, periods, clit, camel toe. I mean… my poetry, it’s not beautiful. I’m sure I can come first at an ugly contest but I can’t win a beauty contest. I am confident I can make things ugly the best. But when it comes to making things beautiful, I am lost.

JL / SS: Is there anything you want to say to American readers about your poetry or as an introduction to your poetry?

KMJ: That’s hard. I’ve never thought about what Americans should think of Korean poetry. Well Koreans write poetry really well. I was glad I was born Korean. It’s good to be a divided country, it’s good to be in a country where the danger of war is always there. It’s a fundamental condition for the poetry that gets written here. And for Korean women writers, for whatever kind of poetry they want to write, I think this country has excellent soil for growing in any direction you want. It’s like a sweet potato patch. You dig up some sweet potatoes, and more sweet potatoes, and no one knows how many are down there. And I think it’s because of the conditions of how we live. Because of Korea, I can’t predict what kind of poetry I will write. I like the energy of unpredictability.