Half-punk, half-easy listening, half-anti-authoritarian troublemaker, half-cheesy lounge music wannabe, how straddling two cultures has shaped my creative life

January 12, 2018

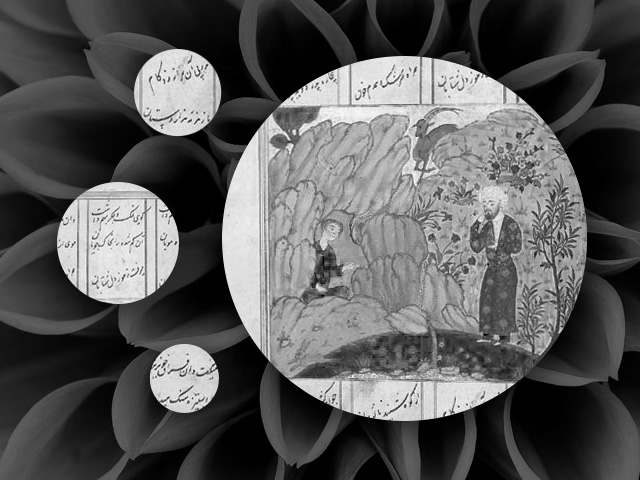

When I was a little tyke my father drove a used vintage 1967 Ford Mustang. It was an iconic symbol of suburban wasteland America, but for the Urdu-language ghazals my dad blasted from his car stereo’s cassette deck. He had found the tapes at an import store in South San Jose, where I grew up. The car had bucket seats and we never wore seat belts. No air conditioning combined with my dad’s chain smoking required the windows to be down at all times. It’s just how we rolled.

While other kids’ parents drove around blasting classic rock, my dad blasted Urdu music. This was not a huge crisis, but it was probably the first time I consciously felt marginalized. In retrospect, it might have seemed like a natural harmonization of opposing forces—vintage Mustangs and Urdu. But it would be several years before I understood the significance.

When my father originally arrived in San Jose in the late-1950s he was one of a few dozen South Asian immigrants in a city of 200,000 at the time. There wasn’t even a separate category for them in the census yet. According to my mom’s account of my dad’s life, he bailed from India as a teenager because he simply wanted to live in a different country. He wanted to be “Westernized,” although she didn’t know what that was supposed to mean. I never understood either. By the time he met my mother, an Anglo-American native of San Jose’s Willow Glen neighborhood, my dad had no South Asian friends and it stayed that way. He didn’t want to hang out with other people from India and he didn’t want to be Indian.

When San Jose began to experience unprecedented growth, immigration increased, yet according to my dad South Asians never seemed to assimilate that much. The way he saw it, South Asians only wanted to hang out with each other and nobody else. As my dad grew older, and drunker, he laughed at his countrymen for refusing to assimilate. He thought they’d fall behind in society. He wanted me to grow up American, so he never taught me Punjabi or anything about India. As result, I never made Indian friends either.

Slowly but surely, my dad’s alcoholism began to get the best of him, leaving me with no real father figure. He was physically present, of course, but he offered no encouraging support of any kind. My mother, a career librarian who raised me in libraries and taught me how to read at age two, became much more of an influence on me in that regard. During grade school I could always read at higher levels than the rest of the class, so other students would ask me how to spell words instead of asking the teacher. For this I have my mom to thank. She also steered me toward musical instruments, while my dad sat around and drank beer with his friends. The doorway into the lost Indian half of myself remained closed.

And so, I escaped into music. When I was eight years old, my mother bought me a used Lowrey Genie home organ, a sizeable clunky boxlike instrument, but with two short keyboards and a dorky lo-fi drum machine with presets like bossa nova, merengue, rock, pop and other styles.

I don’t remember learning how to read sheet music. It’s as if I always knew. I took lessons at Stevens Music in San Jose and quickly assimilated into the great American tradition of cheesy show tunes and insufferable lounge music. By the age of 12, I knew more than any other kid about Lawrence Welk, Noel Coward, Rogers & Hart, Paul Anka, or any other easy listening leftover from the 1970s, good or bad.

We lived in a generic three-bedroom suburban tract house and the organ was located in the spare room, on a hardwood floor with faded white walls. My parents were usually fighting in the living room, or watching TV, so they didn’t seem to care if I was making a racket on the organ. I don’t remember practicing that much, but for our group lessons at Stevens Music, way in the back of the store, down a long, skinny aisle in a back room. I quickly learned how to sight-read basic chord progressions in any key. I could play simplified show tunes, melody in the right hand, chords in the left hand, feet playing bass notes in simple fashion. The rest of the class seemed further behind.

After my father passed away when I was 16, my mom eventually bought me a piano. My musical chops were improving and she wanted me to have a real instrument with a real keyboard. I sat at the piano playing every rock tune I possibly could learn. All the way through my teens, I gobbled up song books from local sheet music stores in San Jose and Los Gatos. It just felt like the right thing to do. I began to amass piles of music, from Led Zeppelin, the Beatles, and Pink Floyd to show tunes, easy listening, or even rock and jazz instructional books. I had no preference—no specific goals at all—but I gravitates toward what was easiest to learn by rote memorization. I privately bashed on the piano and hoped for the best.

Parallel to all of this happening, I grew up listening to rock music on FM radio, and later thrash metal and punk during the latter half of the 1980s. I drove to a zillion shows in San Francisco and Berkeley as soon as I obtained a license. Clubs like The Farm, Rock On Broadway, the Mab, or the Stone in San Francisco were my haunts, and in the East Bay, it was Ruthie’s Inn, Berkeley Square, the Omni or Gilman Street. I must have driven up the freeway 100 times to see shows at all of those places, over several years, yet I still sat at home playing lounge tunes on the piano. I became half punk and half easy listening. Half-snotty anti-authoritarian troublemaker, half-cheesy lounge music wannabe. I straddled two different cultures without feeling completely at home in either one.

This is exactly how I seemed to evolve as a person: half and half. I could never function in just one musical identity, or occupy one favorite genre, one specific pigeonhole. Instead, I was somewhere between two opposing poles. Unapologetically impure. Always navigating the routes between the pigeonholes. I participated in different musical crowds without fully identifying with any of them. Genre-fluid, if you will.

From a flawed Western perspective, the polar opposites of punk and easy listening were not supposed to complement each other, but to me, being half and half, in such a musical fashion, felt normal, raw, and instinctive, but I grew very isolated as a result. No one else seemed to appreciate both Slayer and Lawrence Welk at the same time.

As soon as I began music school at San Jose State University, the interplay of polarities began to deepen. My identity became half-academic music and half-underground rock music. In other words, half-ivory tower, half-street urchin. On the ivory tower side of this split, in school, I studied 20th century avant-garde composers like John Cage, Edgard Varese, Stockhausen, George Crumb, Luciano Berio and a large number of post-Dada troublemakers like the Fluxus movement—stuff completely unknown to all of my friends in the rock clubs of San Jose. The esoteric variety of interests that music school provided me was a blast. I could tear apart synthesizers for a class assignment or create noise collages in Sound Tools—the two-track predecessor to Pro Tools. I could write C code just to make excruciating noises on a UNIX box, or I could amplify shopping carts on stage with homemade contact microphones, all as part of my undergraduate education. I could speed up drum machines to sound like machine guns and also get away with writing dumb Satanic lyrics for 16th century counterpoint exercises. This felt like a dream come true.

To counteract this particular academic half of myself, the street urchin part of me discovered a thriving alternative rock scene beginning to emerge in downtown San Jose at four clubs near the intersection of South First Street and San Salvador: Cactus Club, Marsugi’s, F/X, and the Ajax Lounge. On any given night, I could walk down to that corner and see bands that would later vault to worldwide stardom—like Nirvana, Primus, No Doubt, or Green Day. The web didn’t yet exist. There were no laptops or cell phones. Everything spread by word of mouth, college radio, or flyers tacked on telephone poles. For San Jose, it was a fantastic scene, one that could only have unfolded at that time, at that corner.

But just as before, I felt isolated. Those two poles of attraction—the academic avant-garde and the San Jose rock scene in the bars—did not seem to complement each other. I operated in two different circles of friends, straddling two different cultures without feeling completely at home in either one. In each of those scenarios, I felt like a refugee from the other one.

The half-and-half image of my father listening to Urdu ghazals in a vintage Mustang had not yet returned to me as a metaphor for reconciling those opposites. So I continued to stuff all my feelings inside.

As soon as I began writing, though, what I considered inner conflicts became material for whatever I wanted to write. I felt like a 1000-watt light bulb had finally come to life via a slow dimmer switch. As a journalist and newspaper columnist, I could write a cover story about my friend’s thrash metal photography book or I could interview David Harrington from Kronos Quartet because I’d lived through and studied both of those subjects. Likewise, I could wax poetic about Dee Dee Ramone or chamber music, Black Flag or ballet. Such contrasting musical extremes were simply two sides of the same coin, like the positive and negative poles of a magnet. Each couldn’t exist without the other. Even though I was no longer playing music, I began to find peace in knowing that I hadn’t wasted those years. The music was still in me, but just redirected via the written word.

I began to realize that each previous perspective of half-something and half-something-else was simply a metaphor. My father blasting his Urdu ghazals in that vintage Mustang, in the suburban wastelands of San Jose, launched my hybrid creative life. The only difference is that now, when I ride in someone else’s car, I wear a seatbelt.