Former Open City Fellow Raad Rahman answers ten questions about her writing life

December 8, 2022

“Writing is easy,” Pulitzer Prize–winning sportswriter Red Smith once said. “All you do is sit down at a typewriter and open your veins, and bleed.” Putting pen to paper (or fingers to a keyboard) is never a simple task, even for seasoned writers. Even our Margins and Open City Fellows—and there’s quite a handful of them—can attest to that. Many of them, though, have gone on to write and report for mainstream publications and publish books. In this series, we reached out to our former fellows and asked them to give us a glimpse of their writing lives and to share some tips on how they navigate this creative process called writing.

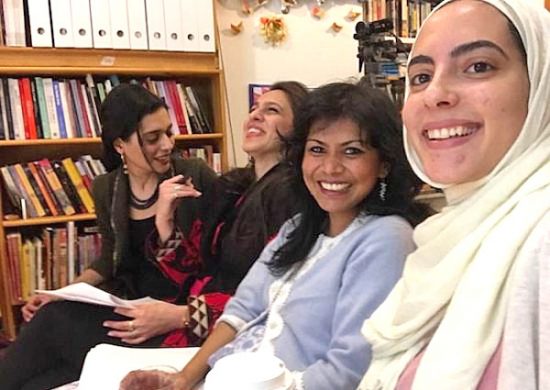

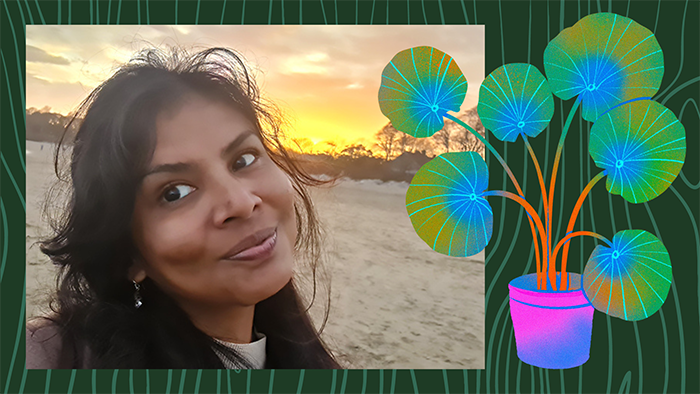

Raad Rahman is a 2017 Open City Fellow. She wrote about her experience with the Survivors of Torture clinic at a NYC medical facility and asked: “While America’s most storied hospital welcomes survivors, your body protests: what did it survive?” in “What Happens After Torture?” In “America Made Me Muslim,” Raad asserted that despite having many parts to her identity—writer, journalist, communications specialist, fundraiser, human rights advocate, sister, daughter, friend—here in the United States, she is reduced to a singular religious aspect of who she is. She mapped the geography of personal and political histories in “Anatomies of Displacement,” detailing her accident while running up the stairs of a subway station, her love for New York City, and her family history intertwined with South Asian history.

Here’s Raad.

—Noel Pangilinan

1. What’s on your nightstand?

Currently, a honeycomb-shaped lamp, a maranta, a rock salt candle holder, and Seven Empty Houses by Samanta Schweblin, translated by the incomparable Megan McDowell. I love the surreal prose and antics of Schweblin’s protagonists.

2. If you had a superpower, what would it be? Why?

I would like to erase national borders and have a free world for all. In recent years, I encountered someone who claimed all asylum seekers and refugees have a singular narrative to tell, and subsequently that an asylum claim is fake if someone isn’t in a detention camp. Imagine thinking one has the right to decide what someone else deserves, unquestioned? No one owes anyone their stories if they don’t want to speak about their personal struggles that may cause them to reevaluate their living circumstances.

No one moves if they’re safe, and national borders can define one’s access to safety. But the larger issue is one of borders and restrictions—how citizenship is contested and construed to further power relations, and how access to finances is prohibitive for those without pathways to the cultural acumen necessary to pursue a better future. If borders were free and national boundaries didn’t fester any petty echo chambers for spewing hate, this would be my ideal world.

3. What’s a typical day for you?

I drink tea or coffee, water my plants, and on most days, I go on a stroll to the park near my house before I start my day. However, no day has ever been typical in the last year, as my family is facing immense persecution at home, and I’ve spent a quarter of this year in numb paralysis while frantically completing freelance work to pay bills. But I try to get in at least a couple of hours of writing or editing on any day.

4. Any writer who influenced you growing up?

As a high school junior, my English teacher suggested I read Louis de Bernières’ Corelli’s Mandolin. I’ve often come back to the lyrical ruminations on the nature of love, and how the emotion can surpass other affiliations, such as that of nationality. Growing up with parents whose families migrated back and forth between India and Bangladesh and Burma and Pakistan—long before these became independent countries—I find national borders to be more nebulous than the rigidity established by patriots looking for absolutes in identity. This book makes me cry each time, and it’s one of the only ones I can quote from memory.

5. What book made you cry?

Many books make me cry, but Daniel Borzutzky’s The Performance of Becoming Human made me reevaluate my perceptions of the systemic cruelties of the refugee experience. I remain humbled by his highlighting of detention and crisis in his precision in documenting the horrifying social dehumanization and denigration of refugees.

6. When do you write best—morning, afternoon, or at night?

I go through phases, but suffice to say I write at all hours, especially when I have a deadline. I used to be a night owl, but I’ve started appreciating the dawn hours more these days. In the morning, the noises are different. Most of the year, sparrows chirp en masse in the maple tree down the block, and as the day breaks, the world begins to rumble. I enjoy ruminating on the colors of the night sky lightening its hues, and being unencumbered by outdoor traffic, undisturbed by anything but my notebook or my laptop. These are hours that are my own, and I don’t have to share them with anyone. There’s a joy in this solitude, and I appreciate being able to write uninterrupted, especially when I am well-rested.

7. Do you have a writing ritual?

This past spring, I forgot to throw out some orange peel, and came back a couple of days later with the inspiration to reenact a nighttime ritual at my childhood home to ward off mosquitoes at dusk. The critters hate the scent of burning citrus, and we burned this peel and fumigated each room in the evenings. I burned the dried peel. Subsequently, I realized the scent unlocks memories and calms me, so I dry and burn orange peels quite regularly now while writing.

8. How and where do you get ideas for your stories?

Photographs, books, newspapers, conversations with my friends, my own life. When I’m reading poetry, I often circle sentences and dog-ear pages from books that I love. When I’m researching, I also stack photographs that interest me on Pinterest and on a folder on my laptop, and I wonder about stories being told from the perspective of a character at the edge of a photograph. What would the world reveal if a side character receives main character treatment? What tilts and shifts fascinates me.

I carry a notebook and make notes on my phone about interesting or bizarre things I have overheard on the subway, and I keep a sporadic journal that explores my own feelings over time.

Newspapers and old magazines are my favorite—especially the archives. These provide imprints of cultural zeitgeists and remain critical primary source material in painting the world around a place and time. While researching archives from Allen’s Indian Mail, the Madras Mail, and the Journal of the National Indian Association from the 1880s for a side project on my great-grandfather’s prolific involvement in furthering Muslim women’s education in undivided Bengal, I chanced upon advertisements for the best raincoats to wear in the Indian subcontinent. The advertisement expounded on how this raincoat was so great, not even an umbrella would be needed for the British gentlemen traveling to South Asia.

I am mesmerized by the absurdity of such an assertion, that any coat can withstand the torrential downpours of the South Asian monsoon. I’ve made a mental note of this—should I ever try to write something about the era in fiction form, I now have a stash of interesting information about raincoats, on the leather that was popular and the tanneries which were not, and the absurd classification systems of the British empire, which continually produced articles trying to compare Indian weddings to the throngs in the early morning at Covent Garden Market (which certainly isn’t as crowded these days as they must have been back in the late nineteenth century). Unpacking these facts provides a treasure trove of inspiration.

9. How do you deal with writer’s block?

I don’t believe in writer’s block. Writing exercises and poetry help unlock those days when I’m not feeling inspired, but inspiration is everywhere. If I’m stuck, I write twenty words, any twenty words. Then I look for ways to connect those words, or circle out a word I find intriguing and look up its etymology online. The origins of words often inspire me to find connections and ways of thinking that I didn’t consider prior. As I adore learning about nonhuman consciousness, I often also watch nature documentaries and imagine the world through the eyes of animals, and I often find this to be inspiring.

10. Did you ever consider writing under a pseudonym?

Now, that would be too telling, wouldn’t it? I plead the fifth on any version of this question.

Other stories in The Writing Life series:

“I Write Best While Having and After a Good Cry” by Nadia Misir

“Every Piece of Writing Should Express or Represent” by Mohamad Saleh

“When You’re Interviewing, You’re the One in Charge” by Eveline Chao

“Just Listen, Really Listen” by Roja Heydarpour

“No Other Way to Be a Writer Except to Be Alone in a Room” by Anelise Chen

That Which You Are Afraid to Write, Write It” by huiying b. chan

“Cut Down the Quotes . . . Include Only Gemlike Phrases” by E. Tammy Kim

“I Am Still Developing as a Writer” by Hannah Bae

“Write a Sentence—Any Sentence—No Matter How Bad It Is” by Astha Rajvanshi

“Intuition Is My Main Tool” by Chaya Babu

“Writer’s Block? What’s That?” by Humera Afridi