Janice Lee on becoming the badger, Navneet Alang on baby names, new hopes, and familial history, Maya Mackrandilal on culture shaping art.

December 12, 2017

Last time, we talked about heroes. Who is the star? Moreover, who is the central figure in the story, that does the work, saves the day, and what does that mean exactly—to save the day? We were able to discover a little bit about conflicted narratives of centrality. This week, we’re looking into things that don’t quite add up. In these gaps, we discover truths of a wide spectrum, from heartening to scary. Navneet Alang on baby names from nowhere (re: everywhere) and Janice Lee on becoming the badger.

The Aesthetics of Empire: Neoclassical Art and White Supremacy by Maya Mackrandilal

There have been recent debates on the demolition of Confederate statues, mostly concerning cries of “erasure” from those who beg for the statues to remain. Mackrandilal dives in headfirst to discuss the actual erasure happening here: the way that a white power has shaped the way that art dictates who gets to be seen as human.

In order to fully understand the stakes of our present, we must dig down into the roots, into the dirt, into the things buried that feed the leaves above. In Black Marxism Cedric J. Robinson recounts an episode during the Middle Ages where human flesh was purportedly sold, roasted, at a stall in a village faire. We can think of this incident as a kind of metaphor for what was occurring in Europe at that time, a kind of self-eating in which the indigenous culture was excised and replaced by a foreign-born ideology, Christianity mixed with the romanticization of the Roman Empire. After this period of plague and self-cannibalization—the destruction of indigenous knowledge, the appropriation of indigenous art into Christian religious art and architecture, the solidification of the bond between church and state—Europe turned its hunger for human flesh and culture outward, to cannibalize the world through colonialism, the transnational slave trade, capitalism, and industrialized war.

Neemakharam by Rajiv Mohabir

Giving, but giving what? Creation as curse. In this poem Mohabir depicts a disconnect between the elements surrounding birth and existence and the outcome.

I am all salt and salt-less.

What can oil-soaked earth bear? God

the father sang me a lullaby,

Neemakharam, neemakharam

I’ve given you the kingdom;

you’ve given me a snake.

Subverting the Western: A Conversation With Hernan Diaz by Aaron Bady

Herman Diaz’s first novel, In the Distance, finds its way through the “canon” of literature regarding the American Western. Except, while writing the novel, Diaz has to figure out exactly what that is. While American cinema has a clear picture of a Western, literature is a little more fuzzy, even though that’s where that genre of tropes originated. In this interview, Diaz explains how he found a way to use that to his advantage.

HD: You know, the Western is such an oddly marginal genre. You’d expect it to be central to the American literary canon, because it’s so perfect as an ideological tool. It’s the culmination of individualism, it’s an ideological tale of the birth of the nation, it romanticizes genocide.… And yet most people will be hard-pressed to name three Western writers before Cormac McCarthy or Larry McMurtry. And it has been overshadowed by film in such an interesting way. Compared to detective fiction or science-fiction—both of which have had massive impacts on literature—the Western didn’t fulfill its promise or it potential.

To Give a Name to It by Navneet Alang

Baby names are sweet: they hold a promise of character, of newness, of you, of hope. This is how Navneet Alang begins to think about reconciling future and past. When he brings up a possible baby name, a Muslim name, he reflects on how odd it is that he’s drawn to this name, being Sikh and technically Indian. Drawing on a history of partition, a split existence gets a vague stitches to, if not put it back together, make it feel more manageable.

I might be able to explain to a friend the various echoes of my grandmothers’ names—how Iqbal’s use by Muslims and Sikhs evokes a kind of prelapsarian harmony; or that I was once able to tell my ninety-something grandmother Sundar that she was, as her name meant, beautiful, and have her erupt in joy at this rare moment of communication—but it isn’t quite the same. Culture isn’t about disconnected parts, put together—it’s about how small things fit into bigger things. The resonance of a name, the echoes of decades past carried in a few words or a knowing look, the sense of a household immersed in the bustle and smells and sounds of a music-filled meal preparation—these aren’t things that translate easily, because they will only ever be orphaned parts of an experience, incomplete and half-told. Like too much in my life, the significance of Tasneen would remain partially obscured, forever in need of some extra layer of explanation.

The Reading Life with Parul Sehgal by Durga Chew-Bose

Chew-Bose profiles prolific literary critic, Parul Sehgal, a “precise and alive” writer and person, to get to the bottom of criticism as a way of understanding and learning, instead of a door to be shut and locked.

In terms of a larger plan—I’m working on longer pieces and have a vague book idea. But the task is always to write every single piece like it’s your only one. It has to have that energy. Use your best material now. Just squander yourself. Enjoy it. I don’t want to read anyone’s tepid writing. For the critic (or any writer, really), your first mandate is get the reader’s attention and then keep it. All your fine thoughts and nuanced interpretations are worthless if no one bothers to get to them. Fundamentally your job is to keep somebody reading. Sentence by sentence. You have to hold them. Sentence by sentence. Demonstrate authority. Books deserve it.

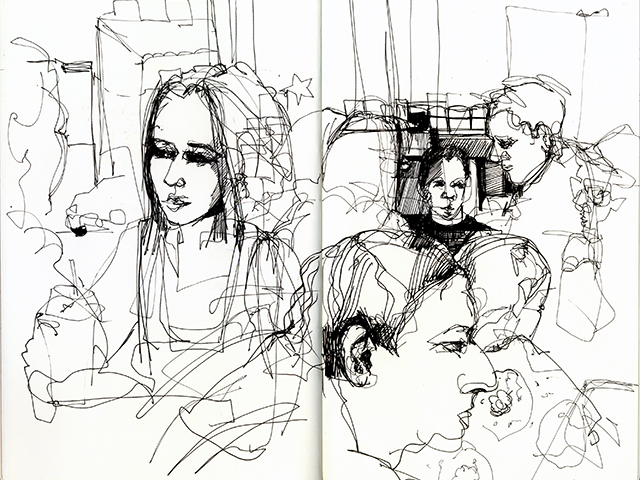

Consider the Badger by Janice Lee

To understand his prey, a hunter becomes deer, otter, fox, badger. Lee assigns this exercise to her class, to write from a non-human point of view. A student resists and Lee then discusses how the distance between human to human is likely the same sort of distance between human to badger, in that we can only form ideas of what it’s like based on what our observations, filtered through our own collection of being, tell us.

And power is an accumulation of all the hierarchies we have created via our senses (smell, sight, hearing) and systems of articulation (language). Because we insist on increased simultaneity, we don’t know to negotiate each of these hierarchies, or that we can, and therefore are complacent, and that is hegemony. But simultaneity also offers choice. We look at each other. We look at the badger. We can move past looking. We can choose what to look at and what to see and how we want to be in the world. What one sees is tied to how one sees. The sky, of course, has not always been seen as blue.

One man’s mission to make you rethink The Simpsons’ Apu by Kemi Alemoru

Hari Kondabolu is on a mission to bring Apu into dialogue. In his new documentary, The Problem with Apu, he tries to draw together the disconnect between a minor character and what his portrayal led to for an entire group of people.

Hari Kondabolu: I can take a joke but it’s been the same joke for 30 years. Can you say the same joke over and over again and still find it funny? For the longest time, the joke telling has been one-sided. I and other Indians had no opportunity to reply due to a lack of representation. My job is to be critical of things, my job is to find the funny in things, and the documentary is funny. The Simpsons critiques pop culture better than anybody else. So what’s more of a Simpsons move than going after The Simpsons?

Love in the New World by Min Jin Lee

A history of trauma culminates in an immigration story, which leads to hard work, struggle—and love. Lee meets a man on the direct opposite side of her parent’s historical conflict, the colonization of Korea by Japan. Her father immediately disowns her, but she is confident that the mingling of American culture in which she grew up means that love across the boundaries is possible.

Then I fell in love with Chris, who was not only not Korean, but he was half Japanese. Chris’s maternal grandfather, Chuji Kabayama, was a count before the peerage was abolished. His great grandfather was a governor of Taiwan when Japan colonized Taiwan. My Korean grandmother lost her sons, her country and starved, while Chris’s Japanese grandmother educated her son at Amherst while eating white rice and fish every day. Of course, none of this had figured when I asked a nice looking boy to dance.

That Sunday night, immediately after Chris took the train back to New York, I phoned my parents. I told them that I’d been dating someone for over a year, that I had fallen in love, and that I was going to marry him. He was not Korean.

“If you marry him, you are not my daughter,” my father said and hung up the phone. They would not pay for my school.