Min Jin Lee talks with Lillian Li about researching and revising a novel, her relationship to her readership, and what’s next in line after Pachinko.

August 1, 2018

Min Jin Lee often signs her books, “We are family.” I mention this because I have attempted to describe the effect her work has on readers, and I cannot say it better than that. To read her books (Free Food For Millionaires and Pachinko) is to be inducted into a family of characters, to feel that you have always known these fictional people, and to feel also, paradoxically, that you have always taken them for granted.

Certainly, because Lee writes about communities that are hidden in the margins of art and life. Free Food looks at a Korean family in New York, the Hans, as they navigate the dizzying gaps between generation and class, and Pachinko unearths the histories of the ethnically Korean Japanese, following one family, the Baeks, as they lose their roots to their motherland while remaining eternal foreigners in their adoptive country. But also because before Lee affixed her attentive gaze over yours, you did not notice the “plush” sensuality of a side character’s “thickly rounded arms and swollen belly,” nor the way he resembles “a self-satisfied seal gliding across a city street.” You did not expect, in a book focusing on the Baek family, to delve into the loneliness and longing of the Japanese wife of Mozasu Baek’s childhood friend Haruhi when she stumbles onto a lover’s park, nor did you expect to feel so deeply for a character you meet in so few pages. It is Lee’s intense, almost adoring attention to both the major and the minor that has made her work beloved. When the author is this in love with the world and the people in it, it is difficult not to fall head over heels yourself.

I met Lee when I helped run a roundtable discussion during her visit to the University of Michigan’s Helen Zell Writers’ Program. The room was packed, not just with people, but with the nervous energy that follows any guest of massive talent. As if she could sense that energy, Lee spent the first ten minutes not only learning and writing down everyone’s name, but also asking after the etymological and personal histories of each moniker. For the next hour, Lee spoke of craft and heart in equal measure. When a student asked her how to structure a novel, she responded first to the pained look on his face, telling him that he was far more capable than he realized. When I walked her back to her hotel, she turned that same benevolent eye onto me. We talked about the upcoming launch of my first book, and after withstanding all my nervous questions, Lee turned to me and said, “But you already know what to do.”

In her work, and in her presence, Lee makes you feel seen and appreciated. We conducted the following interview over email, while Lee was on a global tour. Of course, at the end, she was the one thanking me. What’s more, I believed her.

—Lillian Li

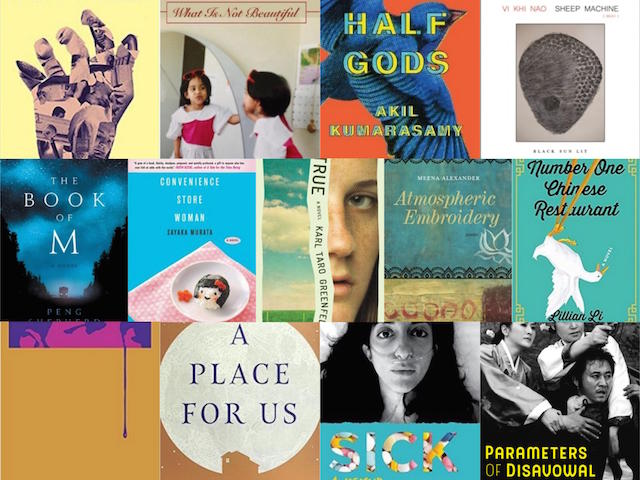

Lillian Li

Pachinko feels like one of those books that elicits strong emotional responses from its readers. What has surprised you most about those reader responses?

Min Jin Lee

I never expected to have so many readers who feel so strongly about my work. Ever. It is incredibly humbling to have readers respond to your work and to care enough to understand your intentions. I am grateful to readers for giving me their time. This is quite an extraordinary thing in our age when attention is so scarce.

LL

Yet your attention—to detail, to character—feels so abundant. For example, your character descriptions feel vivid and physical in a way that I don’t think I’ve seen in most contemporary fiction. Can you talk a little about the process of capturing the physical details of your characters?

MJL

I love the variety of human beings—our shapes, smells, and bumpiness. I find the media’s representation of beauty so jarring compared to what I see in my real life and what I admire. I’ve worked in a museum and in an art gallery, and visual artists understand far better than writers about the complexity of real beauty. There is great benefit to studying the way visual artists work. I recommend the slim book Art & Fear: Observations On the Perils (and Rewards) of Artmaking.

LL

I feel like you’re a writer who could put together a bibliography of research almost as long as the novel itself. How do you conduct research for a book?

MJL

I read as much of the important academic research on the field as possible, then I read mainstream media reporting. Around the same time, I interview and do fieldwork. I am a social scientist/scholar/journalist wanna-be. I have tremendous admiration for what academics and reporters do to create new research and to report stories, respectively. I couldn’t write either book without imitating academic methods for research.

LL

I’ve heard you say that your writing process is to write, then do research, then rewrite, then do more research, then more rewriting. Is this really the case?

MJL

I find that [conducting] personal interviews requires me to totally revise whole books. It’s baffling how wrong or misleading written records can be, not because writers are incorrect, but because people are exceptional and routinely disrupt the well-evidenced theses of historians, anthropologists, sociologists, et al. If scholar X says that Y people are liberal, it is possible to find an exception to this theory by just meeting one Y person who is conservative. In addition, my interviews have led me to rethink everything, because well-written research always has a strong point of view, whereas human beings are inconsistent and less well-defined.

LL

That kind of revision—the kind that razes everything to the ground in order to start anew—is most writers’ worst nightmares! Has that kind of vigorous revision ever led you to write something you weren’t totally happy with?

MJL

I have a clear vision of the kinds of books I want to write. I know it is discouraging to have to burn down the barn, but I have never been unsatisfied with writing a new draft. The new draft approaches the vision, and this is deeply seductive for me. I have made peace with the fact that I am not a fast writer. I admire fast writers. That’s just not my writing process.

LL

I’ve heard that each of your books took almost a decade to write. Spending that much time with your characters must make them indelible to you after a while. In general, your characters are phenomenally drawn, even the minor ones.

MJL

For example, in Free Food we only meet Mary Ellen Currie, Casey Han’s ex-boyfriend’s mother, once, but she still remains so sharp in my mind that I didn’t even have to look up her name to write this question. This was the moment she clicked in my mind, when she’s comforting Casey: “Take a breath,” Mary Ellen said, taking a dramatic one herself, as if she were reading the part of the Big Bad Wolf for the neighborhood children during story hour.

LL

It’s absolutely perfect. I get the entire person in one line. I get her kindness, her maternal warmth, her resourcefulness, and also her plain practicality. Basically, how do you do this? And why spend the time to make the minor characters as unforgettable as your main ones?

MJL

All my life, I have felt like a minor character, and I do not mind. Most writers feel more comfortable watching and knowing things without ever being recognized. I love people who are rarely noticed. I am profoundly uncomfortable with attention, and I have to work very hard when I am in front of people to put them and myself at ease. I say this because when I write, I can make every person vivid. This is within my grasp. I know that even if a person is quiet, not terribly special looking, nor accomplished, that person can be vital for a moment or vital to another person. It’s my job to notice those moments and put it down on paper so it fits into the story. Writers of fiction are creating worlds, and that requires tremendous emotional color, and noticing what people are truly like is something I enjoy.

LL

I feel like your readers can sense that enjoyment in your words. It colors even the bleakest moments in your novels. The experience of reading Pachinko is an uplifting one, which surprised me. It’s not that the violence against the ethnically Korean community was muted or hidden, but looking back, I saw that a lot of the most horrific moments—Isaak’s imprisonment, Yoseb living through the Nagasaki atomic bombing, many of the more violent deaths—happen off-screen, and are told to us by through a grapevine of other characters. Was this a purposeful choice?

MJL

The imagination is very powerful, and we can understand how difficult a terrible trial can be without seeing it graphically. In a way, I think the more graphic certain violent scenes are, the less emotionally resonant they are. As a people, we are becoming more inured to violence and gore, and yet, we are still no less vulnerable to pain. I trust the imagination of the reader. I respect its breadth and scope.

LL

Part of the deep pleasure of reading multiple books by the same author is seeing how they identify their writing strengths, and build upon them book after book. I experienced that reading Free Food and Pachinko back-to-back, and I wondered if that was something you ever think of consciously, writing toward your strengths. If so, what are they?

MJL

My strength is my ability to see the sensitivity of all people. Here, I am going say something weird: I love people. I don’t like all people, but I love all people, and by that I mean I try very hard to understand what a person wants and how she sees herself as she lives. When you look for the very best in what a person is or wants to be, you can start to imagine their life. The narrator is playing God, but of course, narrators are not God. When I consider God, one of the things I think about is if God is God and not some man-made puppet, then God must be aware of the human’s profound vulnerability and weakness, and I reflect on this a lot when I write about my characters.

LL

What reader did you envision when you wrote Free Food and Pachinko?

MJL

When I write initial drafts, I think of my younger sister who thinks I’m wonderful. I’m kidding a bit, but I’m not. I find it helpful to think of a kind, loving person who values me. When I write, I am gentle with myself. When I re-write or edit, at best, I try to be detached and as smart as I can be, but never am I unkind to my writer-self. When I teach writing, I ask my students to please, please be gentle and generous with your creative self.

LL

I’ve heard that you’re working on a trilogy, with Free Food and Pachinko being the first two parts, and the third investigating Korean cram schools. How are you positioning your novels to be in conversation with each other?

MJL

My trilogy is called “The Koreans,” and it is a study of diaspora and how it affects a people from a once unified nation. My next book, American Hagwon, will focus on what education means to the Koreans, and moreover, I want to understand how to live a wise life. I want to explore how we understand education and how it is related to wisdom.