Land holds so much of our history and memory—both personal and collective. In this special folio, seven writers investigate and explore Asian relationships with land.

Land holds so much of our history and memory—both personal and collective. Even when we leave land behind, our connection to it continues to evolve, shaping our futures. In this special folio, seven writers investigate and explore Asian relationships with land. The legacy of land can be unbelievably fraught, subject to both internal and external politics and violence. Family, identity, community, and legacy are the layers on which these complicated, frustrating, and hopeful relationships with land are built. The stories we tell about land have power. They can work to reclaim what we lost on it and create new pathways. They can mourn, inspire, and surprise. These pieces offer a window into the possibility and power of land.

The first pieces in the folio reclaim indigenous storytelling structures and forms, rejecting the colonial impulse for straightforward narrative. K-Ming Chang’s “An Aquatic History of My Family,” which is based on indigenous Tayal Taiwanese oral storytelling styles, uses myth to explore land as absence and the ways in which Indigenous relationships to land and water have been both maintained through storytelling and shattered by colonial violence. Jill Damatac’s “Dirty Kitchen” weaves memory, indigenous spirituality, Filipino history, and recipes to challenge assumptions about the role food plays in diaspora and postcolonial identity. Reimagining lives and identities without the fractures caused by imperialism, immigration, and racism is itself a subversive act.

Land can be the site and source of pain and violence, but it can also leave a physical and emotional legacy for reconnection and transformation. In her poem “three sorry prayers,” Connie Chiu works to process imperial violence and her family’s refugeehood from Laos to California, reconnecting to a physical and metaphorical homeland. Immigrant and refugee identity are often formed in the absence of land, but its unexpected legacies can also give way to a certain kind of inspiration. In “Blood Memory,” Elisabeth Sherman explores her ongoing journey to use Indonesian food to reconnect to a legacy suppressed by generations of imperialism and trauma. The essay, which weaves imperial history into loving descriptions of nasi goreng and babi kecap, explores the generational divide that often defines diasporic families. There’s an element of frustration, but also hope, to this kind of reconnection.

Understanding legacy means grappling with questions of ownership, inheritance, and property. What does it mean to own and occupy land? Even the simplest inheritance can divide a family or a community. In “A Radiant Home,” a sharp, surprising short story by Meghna Rao, a woman in Udupi, India defies her family in her attempt to sell her ancestral home and move to a modern condo. This irreverent perspective on land challenges the narrative of inevitable dilution of attachment to land and culture. The shifting and often contested status of land ownership mirrors personal and collective struggles for agency. Historical strife—both internal and external—over the personal and communal nature of land are also central to the way many of us relate to land.

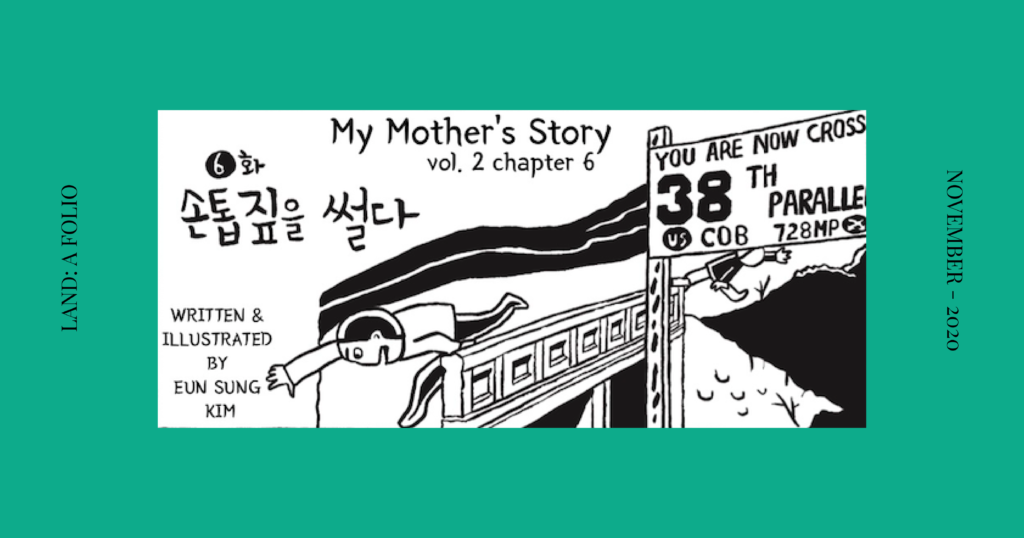

In an excerpt from “My Mother’s Story,” a four-volume graphic novel series that was a national bestseller in Korea, the author’s mother witnesses villagers wrestle with questions about the land they have inherited over family generations, versus the ‘communal’ property now being seized and redistributed by the new North Korean communist government. At the end of the excerpt, the author sits down with her mother for a poignant discussion about generational differences and the need for land reform. These differences are often exacerbated and complicated by diasporic disconnection. Katie Gee Salisbury’s essay, “The Old House In Sam Bat,” narrates her journey to visit an ancestral family home in rural China that her family left behind when they immigrated to the United States. The essay, which questions the meaning and value of land, explores the fractured paths created by immigration and the tenuous family connections supported and tested by land.

These connections, forged across distance and time, remind us that land can be a memory, a record, a tool, or something else entirely.

— Joseph Lee

Contents: AN AQUATIC HISTORY OF MY FAMILY by K-Ming Chang | DIRTY KITCHEN by Jill Damatac | THREE SORRY PRAYERS by Connie Ni Chiu

Table of Contents

AN AQUATIC HISTORY OF MY FAMILY by K-Ming Chang

First was the great-great-grandmother who married a whale.

DIRTY KITCHEN by Jill Damatac

Sisig is a reminder. It reminds you, as it sizzles in its cast-iron pan, of transformation brought only by fire.

THREE SORRY PRAYERS by Connie Ni Chiu

we inherited sickly / roots our ancestors couldn’t plant / deep enough to / grow

BLOOD MEMORY by Elisabeth Sherman

Paragraph by paragraph I am piecing together the story of my Indonesian family—their trauma and struggle against colonial rule—alongside my dad.

A RADIANT HOME by Meghna Rao

She was a prisoner in this home, where death and decay had collected like a fog.