She, like the others, could only slightly feel the edge of some thoughts, and some memories. It was better that way, they all agreed.

February 25, 2021

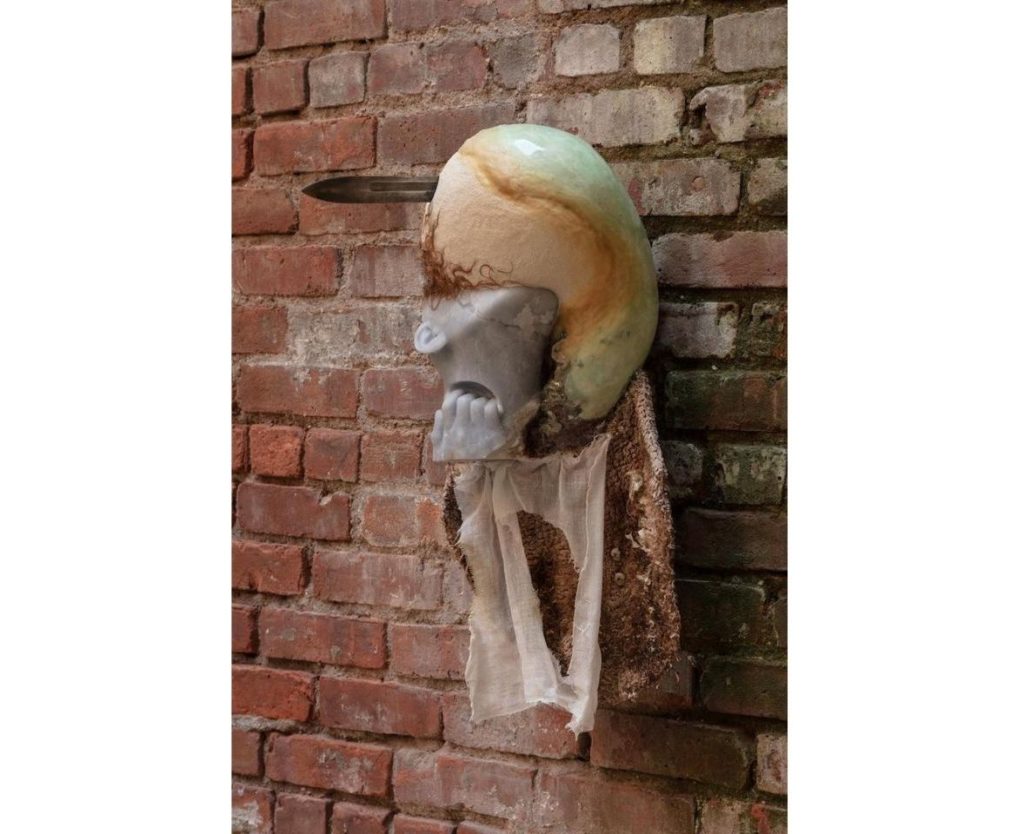

Editor’s Note: The following short work of science fiction is part of the notebook #WeToo, a collection published across the Journal of Asian American Studies and The Margins. Together, this body of work provides language and theory for lived experiences of sexual violence in what is usually dismissed as privileged, unafflicted model-minority life. The #WeToo collection is edited by erin Khuê Ninh and Shireen Roshanravan. Accompanying the series on The Margins is artwork by Catalina Ouyang.

The following work includes mention of sexual violence. Please take care while reading.

Read more from the series here. And continue reading work from the full collection in the February 2021 issue of the Journal of Asian American Studies, which you can purchase here.

Here it is. The machine on your dresser.

Turn the pages, and you may understand. Or,

close your eyes and refuse, your eyelashes now stitched to your skin.

Remember how you’re read.

Or, you may begin and end.

You have a body. You have a mind.

The instructions felt plain and odd.

A bit too demanding, authoritative, and yet intriguing.

Lilith was intrigued, and when reading the directions, she felt warm pleasurable sensations that soothed and covered over her body.

“I have a body,” she murmured to herself as she held up the small piece of digital paper that came with the mid sized white plastic box. Translucent to the touch and sparking rapid glinting blue text—digital paper never seemed boring. You learned as a child that it could cut you, deeply, this digital paper. If you angled it ever so slightly, even just the corner, when a small edge kissed your skin.

Blood. The cut.

You have a body.

Of course, she knew this. She has a body. She has a mind.

Blood never flowed from cuts, or rather, a translucent ooze seemed to flow—

Growing up, the everyday maintained its power like a thick fog. It ensnared Lilith and the others—all their thoughts. It ensured they never remembered the body. Like the others, she moved through the world with a grey haze that covered over each thought that came, and then left her head.

The fog seemed to follow her, then penetrate her, until there were no memories of her body left. Of course, some parts would signal a slight attention. For example, when she was a teenager, her left foot, right above her heel on her ankle, would infrequently vibrate before she went to bed. Why was her foot cut here, Lilith asked her mother when with her fingers she softly explored the scar, a bit of raised pink fresh, thin like the edge of a sweet wafer. She was always rediscovering the scar when bathing.

Her mother would repeat without pause a story: when she was a toddler running in the grass, Lilith was cut by a large uncontrollable nasty black metal sprinkler with eight heads. A playful child, her mother mused, and concluded the story with a scene that Lilith found unbelievable: her father carried her safely home. The story meant to make Lilith feel safe, instead it brought perturbing questions of how or rather if her father carried her home. Though the story explained the scar, even after hearing it, the scar still seemed to be mysterious. “Do you want me to make it disappear?” Her mother asked one day, when Lilith requested the story again. “No,” Lilith said. Even as a child she wanted to retain the edge of her body, the skin that was slightly raised like a grooved border of a small country on a globe.

Stories disappear. So do metal sprinklers. And thoughts. Not scars.

There were none anymore anyways. Sprinklers, to be exact, they were extinct. The disappearance of grass made water that spurted out of metal obsolete. Like books, and some memories. Lilith sometimes tried to retrieve parts of memory, but she couldn’t. The urge was there, but memories would only come when they wanted, not on demand.

Hearing her mother’s story made the scar less vivid, and it seemed to stray any edge of a memory she had left. The reason why Lilith asked again and again was because she promptly forgot the story right after hearing it. It was not common to feel or look at her feet. After a while, like other little moms, Lilith’s use of her feet eventually disappeared and was replaced only with the sensation of walking and moving. The only feeling she had in her legs was when simulating exercise or a bath. Sometimes, she shook her head, and the sharp edges of memory appeared. It was like that one eyelash on your pupil, it slightly irritated her because she could not see it, only feel it. The irritation remained until it was gone without reason. She, like the others, could only slightly feel the edge of some thoughts, and some memories. It was better that way, they all agreed.

Living with the constant nag of the loss of something familiar that you never knew—that was the state of being.

The experts. Psychologists of all kinds. Those professors, and the dragon mothers debated screen after screen after screen about the effect of multiple screens and screen time in the home, and in the larger world. They never seemed to ask the people what they wanted or needed. It was decided for the people because they all must continue on.

The screens helped, Lilith surmised. She didn’t care about signal culture. She considered the talking heads noise. Either way, she always shut them off.

So what if no one had to really leave, except into the screen?

Without screens, how else would you know where to go?

Lilith could move through the world without much thinking anyways. With father’s permissions and access, she traveled more freely and frequently than others. She wasn’t like the common civilians. Due to her family’s access, and specifically her father’s, she could travel and purchase more than other young women. This, she knew, but promptly ignored.

Privilege, like the body, was often understood as an archaic word and concept. Why bother? She never meant or did anyone harm. She was all about goodwill. Goodwill was her middle name. Anyway, her focus was shopping. Her Sunday shopping was the delightful afternoon she looked forward to.

Monday, Tuesday happy day. Wednesday Thursday happy day. Saturday Sunday happy day, Lilith hummed to herself while trying on the latest styles.

Rodeo Drive always stocked up on the new designs along with holiday decorations. Sensations decorated the street and brushed past her eyes. The moving storefronts made it feel like she was walking, even if she was really sitting still. For fun, her girlfriends, the gaggle of chicks who, just like her, loved to shop, made it a point to schedule a tasting at an artisanal sweets shop. Of course, they never really ate anything. They just plugged in.

Plugging felt so much better than the real thing. Plugging in, they felt the sweetness melt over their tongues, but their bodies remained lithe, forgotten, and all the same. Everyone wants to be enticed sometimes. Everyone likes a warm chocolate chip brownie.

Food was in packets and in small glass bottles. Food was pills, filled with vitamins and nutrients and everything one needs. Food never changed from when she was a baby. It was all baby food. Adult food. Baby food. What is the difference? The colors were so bland: green, grey, and orange. Nothing else.

The government was too lazy (or repressive) to change the pyramid. They ran the announcements on the screens, and tried to make the pills and packets seem enticing. If they couldn’t do so with color, they did so with graphics and branding. Large words overtook the small packets and pills. You ate the words.

Boring words. This was food, they insisted. Food was just compact and processed in a healthy, perfect, and economical way. In green, grey, and orange.

When the young people began to raise the importance of the history of food groups and colors, the officials recoiled and rebuffed. The officials, they directed the makers of food to paste more graphics and more branding onto more pills.

The young people insisted it was not a pyramid anymore, but a diamond. Why must they eat from diagrams? They began to ask, shouldn’t there be more colors, sizes, and textures? Taste?

Food wasn’t always this way. Food, glorious food. Hot dogs and mustard. Once they began to demand and find each other, the collective thoughts grew and gathered, and soon would implode and erupt. But instead of erupting, the officials sewed them up, and tossed the collective thoughts somewhere. Food as thought or memory couldn’t be retrieved by the people, although the history of hunger remained written faintly somewhere.

It often seemed like when the young people began to think, and especially when they thought together, “They”—the officials—confined the thoughts as soon as they could. Food thoughts were dangerous. How to articulate the difference between a question, an eruption, an implosion, or a demand? Moreover, the contours of hunger cannot be ignored.

If you were bored of a color, you could order a filter to change the colors of food into something different—neon to be precise.

But who wanted to eat neon food?

When hungry, one cannot think of anything else

except for food.

Starving is a process.

Not a question.

Lilith simply chose to cut out when she had to feed.

It was better that way, Lilith thought when she scheduled the times, clicking away on the small grey controller that was imprinted on her right thigh. She didn’t care about food and their colors.

Cutting Out:

It was then she closed her eyes.

Everything went hazy, then blank.

Although she wouldn’t repeat it to anyone, she saw colors before it went dark. The colors were multiple, and intoxicating. They came back as sensations into her head that she couldn’t describe nor would she ever dare. The colors evoked feelings she didn’t remember nor understand, but ones that she felt. Nevertheless, the sensations and the colors made sense somehow.

All this she had to be quiet about. She couldn’t tell anyone else, not even herself. In the rare quiet moments she had, these colors appeared and covered over her eyes, a mosaic within the dark.

She was constantly plugged in, and one of the lucky ones—there were no pauses to her connection. But the colors. Undetected by anyone else. Sometimes, when she’d admit it, she wondered if they were even real, if it even happened.

Sometimes, there was an accidental glitch that gave her pause. It was in the spaces between the glitch where she sometimes turned sharply toward her body, and touched herself. She saw the edges of her body then, without any filters, and she felt real. Her numbness disappeared slowly, as she moved her hands in surrender.

Of course, she knew she had a mind.

A mind that reminded her to return and not say.

We all had minds, she thought smugly and seemingly bored by the digital paper that came with the box.

It wasn’t even designed. Just a plain plastic box.

She liked the new red intimate wear she bought, especially with the simulated packaging and evocative graphics of instructions on how to wear it. Intimate wear could come in many colors, except neon and grey, which people could only buy in secret on the black market. But who would want to wear neon anyway?

After looking at the digital paper, and the strange statements,

she wondered why she purchased the machine.

It was a cad, she thought, a cad.

Everyone is trying to sell something.

The machines.

When she took it out of the box, the machine was like a glass jar, and inside there were pieces of paper. Actual paper.

The kind of paper that could cut you, but you’d only bleed

ever so slightly to the touch.

She wasn’t sure what to do, but she realized she should reach inside.

Seeing the paper suddenly jogged a memory she had forgotten.

When she was a young girl,

about nine years old.

The time she found

her mother’s journal by mistake.

A journal.

In elementary school Lilith learned you type your thoughts in journals. The students kept digital journals, transcribing what they learned on the screens about their roles as daughters and soon-to-be wives (little moms).

Lilith absolutely hated morning journal. Once in gleeful defiance and in order to fill the lines, she punched in hundreds of exclamation points and emoticons. Her classmates wondered how Lilith finished her typing so fast. Her teacher, that AI grumpy cat, promptly gave her a failing grade. At home, her mother in a soft way that emerged only at key moments of Lilith’s playfulness, laughed it off. Her mother said gently to her father, it was a creative act, she didn’t know where from…

At nine, and as the only child of a very wealthy family, an absent programmer father, and a preoccupied beautiful mother, Lilith was often bored. It was summer and school was not in session. Summer became a season of dread.

Their house was large, white, and pristine. Lilith’s room was filthy. More frequently than not her mother forgot to place the hologram to cover up the mess. She didn’t know why her room was always in such disarray, her clothes thrown about, her dolls’ faces now green, moldy on the floor, and hidden in the closet.

Her hamster had died long ago, a real hamster. One of the last. A pet she adored as she gently squeezed it, a brown ball of fat fur in her small hands. The big plastic silver cage was still on the ground with the plastic shavings and dried black dung melded to the kaleidoscope of the floor. Her clothes, dolls, toys were strewn about. Along with all her pills for the times she skipped lunch. There was not one place on the floor that she could step without stepping on something.

Lilith named the hamster Casper because it seemed to vanish into its cage like a ghost. Perhaps its naming was a strange premonition. Because like a ghost, the hamster died in a few days. Lilith was told upon its delivery that her father had given her the hamster, that it was a gift from his company. Due to the hamster’s swift death, and her father’s absence from home, he never saw it. It was as if Casper never had the chance to be alive or to be seen.

Her mother made sure to take the body and dispose of it. But the artifacts of Casper’s presence remained for Lilith. When playing, Lilith learned automatically to ignore the cage, the shavings, the plastic wheel, and any thoughts of Casper. When she felt the beginnings of small tears appear, her mother clicked a few buttons, and the feelings that welled up her eyes went away. What remained was the mess of the room, Casper’s remains. Lilith was so used to the squalor that she didn’t know or see otherwise.

When the hologram was on, the room was pristine, clean, and clear. It was then she could play with her things. Everything was okay again. Her father never came into Lilith’s room and so he didn’t know the mess. Even so, it is uncertain if he could or want to see it. Or to see her.

To Lilith, her father was a lurking tall shadow cast in the house, and her mother, a magnet that swiftly rearranged to move closer to catch the disappearing and ever-present shadow, and in the process, left Lilith alone.

Since she was two years old, Lilith took her three pills—orange, green, grey—three times each day for everything to go away. So she wouldn’t remember and wouldn’t know. Taking pills left her empty, and smiling when she had no reason to smile. It became muscle memory—her smile—when practiced every day by invisible command, a beam of curled lips and squinted eyes.

Memories are heavy, pills are light. Small pills rolled and followed the curved routes in her cupped palm. She once learned the hand’s creases were meant to tell a story. But what story?

Young Lilith didn’t have a problem with her room. Nor her dead hamster’s cage. She just didn’t go inside the room when it was not cleaned up. To be accurate, the main feeling she despised was boredom. To be even more accurate, it was her loneliness.

Even children can be lonely.

Screens.

How many days did she sit alone in front of the screen in the kitchen and mess room?

The afternoon she found her mother’s journal, Lilith had decided to go to the vanity room to play by herself. Her mother was sleeping. Her daily nap, when she visited a far-off island for body treatments. Her mother’s eyes were heavy and closed with makeup. Lilith wandered into her mother’s pristine gold and mirrored room. It was always clean and tidy.

Due to the newly installed makeup screens, her mother explained in her calm voice that the vanity room was clean because there was actual makeup you applied to your face, and that Lilith would understand when she was older.

Vanity was an acquired skill and taste.

In the vanity room, her mother placed multiple kinds of cosmetics on her face every morning to change her look. New applications were released weekly, and her mother always made sure to keep updated. Lilith longed to include some makeup to her face, but her mother did not allow her to. Although for Halloween, she was given permission to become a small tiger. Her face was covered in orange, black stripes, and drawn-on white whiskers to complete the costume. RRRRRRR.

What Lilith really loved the most about the room was the smell.

Scent was rare.

Tangy fruity kinds of smells, cinnamon and spicy smells, a garden of gardenias and rose pummeled to a pulp then into an essence that she could smell.

It was smell that technologists couldn’t manufacture.

By the time Lilith was an adult woman, they figured out how to connect the synapses to trigger smell. Yet it still wasn’t the real thing. There were glitches to what they advertised as the most pioneering invention to light. Artificial smell.

In this vanity room, her mother would spritz perfume on her wrists, neck, and the top of her head. The smell would trail through their home. Lilith loved to hug her mother then, when allowed, and it was the smell she felt enveloped by. Those sensations came back and warmed her body, reminding her.

Back to her task, young Lilith looked at the counter of the large silver vanity table, under the gleam of multiple lights.

She found what she was looking for.

The glass bottle was almost like a round pink crystal rock. She picked it out of all the multiple glass bottles of fragrances because it looked like a rock. It was also pink. Her favorite color.

She then pushed the button to the bottle and sprayed.

Her hair, head, and then into the atmosphere of the room.

Frantically spraying, the cloud of smells—of gardenias, of roses, of sunlight—filled her nostrils and all over her body. She felt her body then.

The sensation was so electric that if she could she would’ve run out screaming for help. Perhaps she’d be given a shot to stop the sensations but then perhaps spanked by her mother without her father later knowing. Then placed into punishment time where she’d have to listen to droning educational videos.

But Lilith knew she just needed to wait a bit more. Because after the spritzing stopped, the fragrance and the smell ceased. Disappeared. She held the bottle in her fist, and suddenly wanted to throw it against the wall to watch it burst in a million tiny pink cracks. But that didn’t happen.

No, it was as if she never sprayed anything at all.

Disappeared, she smirked in the mirror as she relaxed and lowered her arms, and set down the bottle. The smells disappeared so fast. Though she felt in some ways when that happened, she disappeared too.

In a few years, she would be on the cusp of growing into a little mother, although it would be a while until then.

She moved to reposition the glass bottle, and when she did, the small vanity dresser seemed to pop open after she accidentally hit it with her elbow.

“Ow,” she said loudly, and then she covered her mouth with her own hands.

She saw her expression in the vanity mirror and then began to make funny faces. She was just about to make her tiger face while pressing some of the digital buttons that could transform her looks again. Although she knew her mother placed parental controls on everything. Before she could even try again, or scowl further, the corner of something peeked out from the open drawer.

The hard corners, the edges. She reached in and touched. She put her hands inside and ran it up and down its spine.

She was surprised at how it felt on her fingers as she carefully pulled and grabbed it.

She placed it on the vanity. She flipped it open and saw there was paper and writing inside.

It was a book.

A short history lesson:

For the past twenty years, there were no books used in schools.

Children learned to read, but they read only digital screens.

Paper became as rare and in demand as ancient tulips once were, given the destruction of trees in the world. And the overwhelming fetishization of plastic.

In her history class, Lilith saw images of books. Once they visited the library to see an archival presentation of books. They seemed ancient and weird. She didn’t fully understand why they ever needed them.

Yet, here was a book in her mother’s vanity. One she never even knew was there. A foreign object.

When she tried to move the pages, she saw that she had to grab them with the fat parts of her fingers. Used to turning pages with a gentle or rough haptic touch, this was a strange sensation for Lilith. She wanted to say “on,” or to find the button. Somehow she knew there was none.

Instinctively, she grasped the paper. It was the only way the pages would turn and she could feel it on her fingers.

Yet, she didn’t want to read at first.

Instead, she took some time to run her fingers down the paper, curious if anything happened. She liked the sensation of touching. But the book laid flat, and the paper didn’t change colors or type or anything.

Is it on?

Though it did nothing, even in her young mind, she just knew.

On.

She hesitated before reading. They had no rules about reading in the house, but she also felt instinctively she shouldn’t. She shouldn’t read her mother’s writing.

But alas, of course, she did.

Read.

She couldn’t seem to understand anything.

It was an old script. Cursive that looped and loped around, and around.

So difficult to decipher. Almost like the messy pink curl of ribbons on a

present or something… She had no idea why people wrote like that.

It didn’t seem natural.

While she couldn’t understand the sections towards the end of the journal, there was text in small blocks not in cursive.

Lilith recognized it as poetry. She learned about poetry in school. It was a kind of ancient language, written in blocks, and rarely used today.

Her mother wrote poems?

Lilith was still learning how to read, but she took the time.

These words, she could read somehow. She must.

She wondered why her mother wouldn’t want her to grow. It made her irritated and curious. These days her mother always seemed sour, frustrated, or flustered. If she was not napping, she often scrolled for hours on the screen that took up one wall of the house.

Her mother’s journal was a book.

Like the books that she saw at the extinct library on their field trip.

Now that almost all books were extinct, with so many more burned and used for rare projects, which occurred about fifty years before she was born.

Lilith wondered about this journal, was it her mother’s book?

She wanted to read more. She was interested to see if there were other poems. The last one, dated three years prior, was about her.

She would turn ten soon, she thought with a drastic transfer of her attention to her upcoming birthday party in a few weeks. Then, she thought about her presents. Her sweet cake. Her new burgundy dress she would wear. Her friend she wanted to invite. And her “friends” she didn’t want to include. And… Then her dog beamed into the room. She remembered it was time for her virtual pets to come visit her. She had a dog, and a red and blue parrot named Toucan Sam.

Today, Milkis, the big white poodle she began to love, would visit her to play.

She promptly forgot the journal and the smells, as Milkis found her in the vanity room. Milkis was as tall as Lilith when standing on her hind legs. She hugged her dog as hard as she could to feel her dog’s body envelop hers like a comforting blanket. Then she whispered, “let’s go.”

The events of the afternoon in the vanity room never happened again.

The next week, bored and curious, Lilith remembered the drawer and went to the dresser while her mother was scrolling. She sucked her breath in anticipation and closed her small eyes as she opened the drawer.

It was empty. There was nothing inside. Suddenly she wondered if the memory happened at all?

Reading the poems, the journal, and her mother’s writing remained a faint vision almost as disturbing as the empty colors of haze. It was like most things—she chose to ignore it automatically without thinking.

Now she was a young woman on the cusp of becoming a little mom, and Lilith found herself studying the machine in front of her intently. It looked remarkably just like the jars in her kitchen. However when the machine beamed into her home, somehow that memory of her mother’s journal came back as a sharp pain in her chest. The memory seemed to blind her momentarily as she took in a deep breath and then gagged for air.

She opened her eyes. She took a breath. Then another. She was okay and calmed now. Though she was concerned, and scared, she continued looking into the box. She couldn’t help herself.

Along with the weird declarations and instructions on digital paper, there was something else. She hesitated but stuck out her hand and pulled out a piece of old paper from the packaging. Her open hand now a clenched fist.

Dear Lillith,

This is a secret feminist poetry machine.

Just listen.

One thing to know is that we’ve always been

translating experience into language.

It is a kind of light.

Yours in solidarity,

The Collective

What kind of language is this? she thought? What is feminist?

Light? The collective?

Yours in solidarity? What the…

And they spelled my name wrong!

She was absolutely confused. Bewildered, and a loss of words, well somewhat. Yet, she found herself snotling from the absurdity too. It eased her constant irritation prompted when things did not make sense.

Lilith grew up to be an intelligent young woman, however, she grew irritated and impatient when things didn’t work.

The letter didn’t irritate her, even if she didn’t understand it. Now, if the machine didn’t work, she would’ve gotten irritated.

She would have to plug it in. Like her hesitation before opening her mother’s journal, she took a breath before doing so. When her hand clicked the button to connect, she watched with awe as the jar lit up with a piercing blue that emitted and almost sent currents into her body. Her eyes were most certainly blue in reflection if you looked into them then. As the light descended, her eyes turned brown again. But Lilith couldn’t see her body even when bathed in light.

Shopping.

She was unsure of what it was when she ordered it online. However, that was not uncharacteristic of her shopping habits. On Sunday, she liked to shop hard.

It was a process akin to exercise, because everything seemed right in the world when she ordered something. The machine was not anything different from the multiple things she purchased regularly and discarded.

Shopping took her away from the nagging list of things she needed to complete by the next year, and the ensuing years. It annoyed her, this list, because she didn’t see how it would work. The simple instructions to her life:

- Grow and learn

- Learn to walk like a woman

- Learn to listen

- Learn to smile

- Get married and become a little mom

(2 – 4 could be in any order, but nothing else)

It seemed incredibly unfair even though she never questioned it. The pills she took daily suppressed sensations of annoyance that never seemed to transform into anger. To avoid the suspension of her shopping privileges, Lilith did as she was told. Her father and mother loved her and taught her that way.

She was at 1 and 2. But she knew 3 – 10 would soon come to pass.

Little Brother didn’t have to follow rules. He had more time to do what he pleased. All he liked were video games anyways. It made her feel awful, really. These rules. When she thought about the misordering of it all, she took more pills to ease her shaking and growing anxiety, fear, and anger that she shouldn’t feel. Couldn’t feel, but she felt the edge there, and then.

Sellers and shopping.

The machine was introduced to her unexpectedly. She was at the virtual coffee shop taking a break from studying feminine manners and gestures. She was readying herself to shop. Lilith was one of the lucky ones, she didn’t struggle with how she should move. She moved perfectly. Especially her face. Her mind was another situation she’d rather not think about.

Suddenly, a glitch seemed to send her a notification. It was an unknown caller.

Lilith often received unknown callers, although her father made sure to block them out with a special application. In fact, he named the program after her, Līlītu. Yet this seller that she didn’t know was somehow able to reach her.

Though she knew better, she answered. She was intrigued.

If one answers, you are transferred to a safe room. There, you meet your seller. Some were frequent sellers, off-Rodeo Drive merchants that wanted Lilith to purchase their items. Lilith promptly ignored them.

Transferred to the safe room, the security wall was set. This meant that Lilith would only have her thoughts and attention on the room. She wouldn’t wander, nor would anything else wander in. Moreover, if she wanted to forget what happened, she could press the keys on her thigh to reprogram the day. Of course, it took some effort. It also took time, and it would still be on record. She would need to be careful. But she was safe.

Everyone likes doing something without permission sometimes. Some more than others. Lilith enjoyed it in moderation, but because it was so rare that an unknown seller would come and request her presence, she replied yes and wondered if she would buy.

With the security wall set, the walls appeared around her, and turned grey. The walls emitted a bright blue. It warmed her face, a mechanism to ensure that one wouldn’t stay too long to shop. Lilith enjoyed the constant hum of currents that ran through her body, she was always plugged in. Now, this room felt different, and it was just a feeling Lilith had and didn’t ignore. She paused before she entered the room because somehow she knew things would change.

They saw each other.

The seller had short red and orange spiky hair. The kind of natural red that was unusual, and rare. Although in vogue a few years ago, it seemed everyone began changing their hair into the rare color, citing steamed carrots and tomatoes as inspiration. Food nostalgia, they called it. Lilith kept her hair dark and brown, and black. She knew rarity didn’t always lead to a sustained beauty standard. That fad faded, she was right.

But this woman with red spiky hair, and a few freckles on the borders of her cheeks and nose seemed… striking. Even before she moved, they made eye contact. Lilith had to look at her.

Everything in the room seemed to freeze and Lilith then saw the woman’s thick hands. She was signing to Lilith. Her hands danced rapidly like bright green glow sticks.

It was then that Lilith felt those sensations again in her body, realizing softly something that felt like wonder. They gazed into each other. Lilith quickly changed her language settings so she could understand her.

Buy this. It’s free. See what you think.

The words were mundane and ordinary for a sale. But Lilith saw the urgency of the woman’s hand gestures, and the way her hazel eyes seemed to pierce into Lilith. The woman was looking at Lilith’s mouth, or was it something else she was looking at?

She should ask how much. But with her budget, she could buy anything. It was not the price, it was the woman’s expression. Her hands. Lilith could not refuse.

The woman said the machine was only ten dollars, and she’d get the money back after turning it on. So the machine was free? Lilith gazed back at the seller but didn’t say a word. She was taught how to be quiet, stoic even, it was more feminine that way. But without a response, the seller gave a terse nod then left the room, moving past the security room walls without saying anything about her identity. But Lilith saw the woman’s screen name: Red.

Red.

Right after Red left, Lilith frantically tried to press the buttons to access the record. She told herself the reason was she didn’t want her father to know. Yet, she knew inside, it was because she wanted to know, who was Red?

There was no record of the seller. It was blank, as if it didn’t happen. As if she was never at the coffee shop taking a break for shopping. As if she never saw Red’s hands. But Lilith returned to the coffee shop by beaming back to the stylish wooden table she was perched at, the table set with a small pink tulip plant. It was then that Lilith received the notification asking if she wanted to purchase the machine. It did happen, she thought.

Immediately, she clicked yes. Another message appeared and showed her the image of the white plastic box. It notified her that she bought a feminist poetry machine. It would arrive the next day.

She was thumbing through the message, in an attempt to obtain more information on Red. Suddenly, it disappeared. It went blank. The message, like the record, was gone. Just Lilith was left.

What Lilith didn’t know.

What she would come to know.

What she would see.

Glass jars didn’t hold actual food. Lilith was familiar with jars. They had many jars in the kitchen with pills and matching labels to know which pill to take. At school, they were once shown photographs of jars with historic foods known as cookies, wafers, and granola. Her teacher said they were sweet and tasty foods. That teacher was taken away soon after. That was such a long time ago that Lilith forgot what a jar could hold otherwise.

This jar was different and jarring for that reason. At first glance, it looked just like the jars in the kitchen, only empty. However, upon a closer look, colorful wires ran along the inside bottom of the jar—red, blue, yellow, green, white, and black. When she peered in closer, the colors were dizzying. There were wires in every appliance and machine, of course, but Lilith never saw them. No one saw them. But this jar, the wires were exposed, all of it a jumbled, colorful, tangled mess if you cared to look closer.

There was paper inside, too. Small pieces of pink paper lay folded on top of the wires. She could not read what was written on them. She had to open the jar.

Lilith reached out her hands to grasp the jar. She didn’t have to hold it with both hands, but intuitively she felt that something was going to change once she opened the lid. Something inside.

The voices emerged slowly and then with a frequency and urgency from the jar. It began as soft phrases, whispers, then a cacophony of raspy screeches, shrieks, and screams. She could have closed the lid. But there was no part of her that wanted to. She had to listen. She had to read.

The voices in high and low octaves spitballed ideas and experiences that provoked thoughts in Lilith’s head. The words from the machine seemed to convene, heckle, and hack. It was the process of transmuting experience into language. Lilith couldn’t believe what was happening, but there was nothing she could do except listen.

The voices didn’t seem to stop until she grabbed a piece of paper that began blinking pink.

He harassed me. He grabbed me. When I refused, he fired me.

She unfolded the paper, and it read

| Sexual Harassment |

Open again.

Open again.

Black women factory workers unfairly fired were deemed either as Black or as women. Not both race and gender. Identified only on a “single-axis.” The ways our identities are shaped, formed, and intersect in this complex world.

The lynching of Black men due to the racist stories from white men and white women…

| Triangulation |

My friend took me out to dinner then he raped me afterward. I knew him. He was not a stranger.

| Date rape |

Ignoring what happened, pretending it didn’t happen, the abuse. The light is dimmed.

| Gaslighting |

Men can’t stop explaining things to me…

| Mansplaining… |

“the specific hatred, dislike, distrust, and prejudice directed toward Black women.”

The invisible borders between… the hybridity of gender, race, and sexuality, the geographical space and identity of neither fully of, or part of Mexico or the United States, negotiating both cultures.

A moment. A movement. #. It happened, the sexual abuse, the harassment, and we will tell, together.

| #metoo |

“the excessive sympathy shown toward male perpetrators of sexual violence,”

The voices of the machine said the last words with finality when she unfolded the remaining paper…

| There is more Lillith. Add yours here. |

Then it was silent. Lilith shivered as it stopped. Instead of being frightened by the cacophony, she felt something different. She felt heard.

She grabbed the pink pieces of paper from the jar and stacked them carefully together in her hand.

They made, she realized. A kind of book.

Lilith’s perfect blank face—with her permanently upturned smile—suddenly crinkled, cracked, and broke open. Her face was like a broken dam as the rivulets slowly began to flow it was the first time in her life that she cried.

Another history lesson.

There was a time when the stories women wrote simply disappeared. She attempted to write, and after she typed, the text disappeared. The text runs into white.

Disappearing before our eyes, our minds unable to process what just happened and what was happening. The text written and disappearing, deleting immediately afterward…

A Library of Feminist Terms:

Mansplaining

Misogynoir

A Library of Feminist Terms:

Mansplaining

A Library of Feminist Terms:

A Library of Feminist Terms

A Library of Feminist

A Library of

A Library

A

At nine, my daughter is bright like a noonday flower

How I hope

She never grows.

At nine, my daughter is bright like a noonday flower

How I hope

At nine, my daughter is bright like a noonday flower

At nine, my daughter is bright like a noonday

At nine, my daughter is bright like a

At nine, my daughter is bright like

At nine, my daughter is bright

At nine, my daughter is

At nine, my daughter

At nine, my

At nine,

At

Where is the quality of this light?

Where is the quality of this

Where is the quality of

Where is the quality

Where is the

Where is

Where

“Library of Lost Poetry Machines” is an excerpt from a larger book manuscript Poetry Machines: Letters to Future Readers (under review at Duke University Press). Poetry Machines includes a diverse collection of auto-theory, documentation, fiction, and critical essays or “letters” on feminism, poetry, race, and technology. It is drawn from an ongoing new media project The Kimchi Poetry Machine exhibited at the Electronic Literature Collection Volume 3. Forthcoming installations and workshops include the Smithsonian Asian American Literary Festival, UB Art Galleries, and Beyond Baroque in Los Angeles (2020/2021).

Pictured above, by Catalina Ouyang, cunt waifu, 2020, exhibition view at Lyles & King, NYC:

“In repeatedly trying to write the meaning(s) of violence

and how gender is incommensurately inscribed upon structures of power

the scene of unprecedented collective violence

Hair soaked in glue

grief is articulated through the body, for instance, by infliction of grievous hurt on oneself,

‘objectifying’ and making present the inner state”