When it comes to how rape culture is enabled, made mundane, what are the hard questions we have not yet posed?

February 16, 2021

Editor’s Note: The following is an introduction to the notebook #WeToo, a collection of essays, poems, creative nonfiction, and experimental works published both in the Journal of Asian American Studies and in part here on The Margins. Together, this body of work provides language and theory for lived experiences of sexual violence in what is usually dismissed as privileged, unafflicted model-minority life. The #WeToo collection is edited by erin Khuê Ninh and Shireen Roshanravan. Accompanying the series on The Margins is artwork by Catalina Ouyang.

The following introduction discusses material related to sexual violence and rape culture. Please take care while reading.

Read six pieces from the #WeToo notebook in the coming days on The Margins. And continue reading work from the full collection in the February 2021 issue of the Journal of Asian American Studies, which you can purchase here.

This introduction, aside from edits for length, appears as written in June 2020 for the Journal of Asian American Studies.

It’s easy for new, green things to get buried in the deluge of a pandemic. In the early days of March 2020, we’d just sent our contributors the first round of pings: Hello, we’re here if you need us. Feel free to send drafts or schedule conversations. Whatever helps you to get to the finish line of May 1.

Rapidly it became clear that the world had lost sight of its future—and very unclear what to do with a college reader on sexual violence, only two or three pieces of which had been so much as drafted.

We decided to continue, yes, but the introduction you’re reading isn’t an essay triumphantly swathed in hindsight. As we send this gathering of writings to the journal—precious as eggs just laid—it is June 2020, mass uprisings against state violence are setting cities ablaze across the globe, and the calendar remains impossible to read beyond a few weeks out.

That in these past few months, our writers have bent to the task of excavating their mind’s sores and their flesh’s memories is generous beyond measure.

Which makes #WeToo: A Reader an act of commitment, of mustering up to the other things in our lives that continue to harm us and those around us. Far from being put on hold, sexual and domestic violence as well as child abuse are some of the few crimes that have spiked since we have been ordered to stay “safer at home.” And even as mass protests to rethink policing in America gain momentum, it becomes increasingly urgent to grapple with the ways we enact and enable the conditions for pervasive interpersonal violence within our own communities.

At the same time, #WeToo: A Reader is an act of optimism, convened by a willed belief that the words we write will reemerge in a future we can continue to plot.

But before #WeToo was a reader, it was a conference panel , and before a conference panel (that did not happen), it was a challenge issued by erin in the 2018 collection Asian American Feminisms and Women of Color Politics, edited by Shireen and Lynn Fujiwara. Written before #MeToo ignited public discourse on sexual assault, the essay admitted to fearing a backlash for what it was about to say:

1) That Asian American feminism had given no time of day to rape or harassment in lives deemed “model minority”—because how could it? In Asian American studies “we do not concern ourselves that the model minority can be raped,” because according to our press releases, “the model minority does not exist.” That people seeming to fit the description of a myth line the halls of higher education and professional or corporate life is inconvenient and generally elided. Meanwhile, for Asian Americans who have made it to the elite institutions of their communities’ fixations, there are “added stakes” to crying assault, when the “bright futures” thereby jeopardized are foremost their own.1

2) That so long as progressive feminism permits only the discussion of (male) perpetrators as agentic subjects in rape culture, it dooms us to a hell of half-truths. The orthodox feminist position on this—that the victim is to be not only “innocent, blameless” but “free of problems (before the abuse)” (Lamb 1999, 108, emphasis added) comes with a dubious corollary: that rape culture produces masculinity, but not femininity; tops, but no bottoms.2 How can the immensity of what we know regarding gender formation—the ways that patriarchal societies raise not only boys to conquer but girls to internalize and perform their own devalued roles—how can either screech to a halt at the party, the date, or the bed?3

And how, given those two resounding refusals in the literature and scholarship on sexual violence, are we to help the Asian American young people in our classrooms navigate the rape culture that is their Greek life, their first adult relationships, their activist organizations, their college professors?

We editors asked JAAS to permit this special issue to take the highly unusual form of a reader for that reason. Our call for submissions asked for poetry, art, fiction, and memoir, as well as scholarship. It asked, When it comes to how rape culture is enabled, made mundane, what are the hard questions we have not yet posed? When it comes to how we learn to fashion self and seek others inside rape culture’s gravity, what are the answers we have not dared frame? What differences does model minority racialization (however well or ill it fits) make to any of this? Its result is the first collection to provide language and theory for lived-experiences of sexual violence in what is usually dismissed as privileged, unafflicted model-minority life. Wrenching and beautiful, these pieces are theory in the flesh, embodiments of the yet-to-be-spoken.

We invoke theory in the flesh as the methodological frame for this collection because it foregrounds the epistemic excess of lived experience, of meanings uncontained by the racial and gender scripts imposed on Asian American bodies. “Born of a politics of necessity,” Cherríe Moraga writes, “theory in the flesh” is “an attempt to bridge the contradictions in our experience.” The pieces in this collection know to dwell there, where it twinges, until the pain releases new learning. They incite us to feel our own entanglement conveyed in the gooseflesh and caught breath of our reading, to register what we recognize in the stories told and the analyses offered. Real talk, these pieces burrow into sedimented layers of long-held cultural assumptions that wire us to act against our own well-being. And, real talk, they don’t stop there, but compel a series of reckonings: What then have we internalized as virtue, the better to eat you with, my dear? The capacity to tolerate the intolerable with grace? The duty to shield elders or leaders—themselves anti-violence activists or artists maybe—with our bodies, if need be? An equal claim to the desires of others, equal impunity for our own?

The intent behind this collection is also reflected in its title. #WeToo critically invokes the now mainstreamed global #MeToo movement, though refuses those bourgeois white carceral feminist politics. This reader heeds instead the Black feminist origins of the movement. Tarana Burke, a Black cis woman who grew up in the Bronx, New York, developed the politics of saying “me too” specifically to address sexual violence experienced by women and girls in her Black community. Burke explains that to say “me too” in a community for which neither the state nor public anti-violence movements register as protector is to say “I agree with you. I am with you. I understand you, and I’m connected to you.” It is important that for Burke the “I” who addresses the “you” and the “you” addressed by the “I” are other survivors and not “women in general” or the criminal justice system. Burke’s “me too” aims, instead, to conjure a community that sees in itself the capacity to repair and transform the cultural fabric through which sexual violence is made invisible, inevitable, and unremarkable.

Our “#WeToo” likewise insists that Asian Americans be heard, believed, and backed up in their experiences with sexual violence—not in an additive sense, but with syntactical difference. The “we” of the title casts for Asian Americans as subjects, not merely objects, inside rape culture. Which is also to say, writing like this is phenomenological: disciplined, self-reflexive, it casts courage like sonar, to find the shapes of structures of feeling in the dark. The results are honesties, equal parts delicate and excruciating, the meanings and ethics of which remain unresolved and in search of collective dialogue.

It is high-risk behavior, for instance, to testify to one’s own faithless yearnings—for the pleasure of pleasing, the desire to be desired—and trust a jury of readers not to convict. “Sometimes a boundary you know you have (or should have) gets crossed, but you find yourself feeling, like, fine or whatever. What should happen then?” asks James McMaster in his attempt to make sense of first loves, first fucks, and Gaysian negotiations with white ex-lovers and suitors. With disarm- ing candor, he marries lyricism and theory to disabuse us of the rules we claim to love by. Amanda Su’s poem explores further the imbrication of unknowingness and the act of sex. Interweaving three stories of carnal ignorance, she details how the myth of liberal individual agency falsely presumes we ought to know what we desire prior to the sexual act and, thereby, inaccurately renders our “choices” as evidences of consent. For some tragedies, no one way to tell the story can suffice.

Our contributors are theorists and poets, activists and artists alike, and so they go about remaking the world through words—binding harms by their true names.6 In “Rape Is/Not a Metaphor,” Juliana Hu Pegues compels us to witness faithfully the “embodied after-effects of quotidian sexual violence” as it shapes her trajectory from the Asian American arts and activist scene into academia. Along the way, she exposes a series of betrayals enacted by comrades and mentors whose radical anti-carceral politics sacrifice her wellbeing to “restore the larger Asian American community,” and grapples with “trying to tell a story about rape while occupying Native land.” This accounting comes to us in a profusion of argots and arguments, unreconciled and irreconcilable, for when the politics are not enough. Gowri Koneswaran tracks it watchfully: the blade of terminology against the skin of her experience. She writes, “The preferred term for people who have experienced sexual abuse is survivor. Mine is someone this happened to once, then again, repeat. / The preferred term for people who have committed these crimes is perpetrator. My preferred term is the ones I have known.” Christine Kitano likewise questions what goes by “luck” or “fortune,” when some of us escape the grips of sexual violence: “Such luck to get home safe / when so many do not; is there really no other word?” Such a humble question, to challenge the ontology of rape. Together, they expose how the language of rape culture, embedded in our tongues, dismisses sexual violence even as we speak of it as the result of bad luck, bad choices, and bad people. To reprogram a culture, they reprogram its language.

But first, a research question, or maybe a riddle: What do you get when you cross model-minority racialization and rape culture? No one knows because it never happens? Or no one knows, because we’re not supposed to say? The road from good little girl to survivor passes through thickets of betrayal, not least of which is the injunction to make oneself no burden on the system. This will feel like silencing, but a victim’s silence is a means, not an end. The mutings before, during, and after are compliance made practice, deference made habitual: obedience-training to always yield the right of way.

Both Michie Sariyama and Miya Sommers find themselves asked to say nothing, for the protection of others more powerful than they, others who ought to have protected them. “‘Please don’t press charges,’” Sariyama’s mother pleads to her, “‘He’s going to kill himself.’ I stared dumbfounded, not knowing how to process her greeting.” What if, rather than a lack where we start our journeys, we see silence for what it takes to get used to? Called “mouthy” by an esteemed elder whose misogyny she has challenged, Sommers finds “The panic is causing all the oxygen to leave my body. I’m shutting down. This is why it doesn’t make sense to fight, the adrenaline whispers to me. If you don’t do anything, you will be safe.” Both grapple with the legacies of Japanese American incarceration—Sariyama in her family’s transmission of trauma and gaman, Sommers via a communal inheritance of activism for social justice. And yet these spaces close ranks the same: around their self-interests, to which the victims are the threat.

Thaomi Michelle Dinh recalls that what language both she and her female friends could access, to make sense of her rape, not only amplified her anguish and confusion but also sabotaged the support she most needed from them. Together with her partner and illustrator, Bryan Dan Trinh, Dinh addresses her younger self, and through that self the younger readers who are likewise finding the trek through rape culture special kind of treacherous, when as “an Asian American woman … [the] world … expects you to be nice and obedient.”

Across three different pieces, toxic masculinity emerges—and toxic femininity, too—as a social project: familial legacy or Asian American com- munal campaign. Angela Liu offers a primer on the online Asian American men’s movement commonly known as MRAsians, an influential conclave that reveres the work of Frank Chin for his elevation of masculinism as a marker of “real” Asian American identity. MRAsians attack Asian American women who date white men or advance feminist critiques of toxic masculinity for reinforcing their racialized emasculation at the hands of white-dominated Hollywood. Not coincidentally, the author of this essay took “Angela Liu” as a pseudonym. As she carefully lays out the movement’s arguments and activities, however, Liu is attentive to the costs MRAsians inflicts not only upon its targets, but upon its own: “Asian American men should be able to make their own choices of what it means to be an Asian man. Yet, it is reification of toxic masculinity—including among adherents of extremist MRAsian antifeminism—that limits masculinity in an endless cycle of rage, recrimination, and violence.”

The work of choosing masculinity differently, Mashuq Mushtaq Deen and Kawika Guillermo both know intimately. In a letter to his mother, Mashuq Mushtaq Deen explores his struggle to tell her that he was raped, and does so from a position of particular insight: “I was a woman (sort of) for thirty years, and now I’m a man, and so the landscape is much more complicated from where I stand.” He ponders how his mother’s teachings—“don’t ever be alone with a boy or bad things will happen”—taught him that to be “a man in the world” is to be something that people should “look at with fear.” But more clearly than most, Deen sees manhood for more than its failures.

Meanwhile, a new father, Guillermo is painfully aware of having queued his son to a lineage of men, and that violence, racism, colonialism are their patrimony. What he calls an “An Ode to Patriarchy” is an undertaking to give “honor and respect in a way that also dismantles that honor” (p. 24)—or that irradiates the patriarch, but spares somehow the man. In his lyric essay, braving that paradox means opening in uncertainty to what his father needs but could never ask—a modality of traditionally “feminine” communication, on the other side of which may lie a nontoxic manhood. We believe these pieces model a feminist critique of masculinity that, as Toni Morrison ever did, fights for the young men we love.

This collection as it goes to press, though, is thinner than originally conceived. Supporting our contributors during a pandemic has meant, in some cases, understanding that they needed all their abilities elsewhere. This issue has served as an unprecedented partnership between JAAS and the Asian American Writers’ Workshop (AAWW). We have all been excited by this opportunity to help bridge the stubborn gap between Asian America’s academic world and its vibrant arts and letters community. Five of the pieces in the #WeToo collection appear both here on The Margins and in the pages of the journal; another six only in the print pages of JAAS; and one story that is only here on The Margins. Our hope is that readers who start at either end of the bridge may cross to the other. So the process of coming into this project and of nurturing it into print in a timely manner reflects the collective politics we see as integral to ending rape culture in Asian America.

—erin Khuê Ninh and Shireen Roshanravan

June 2020

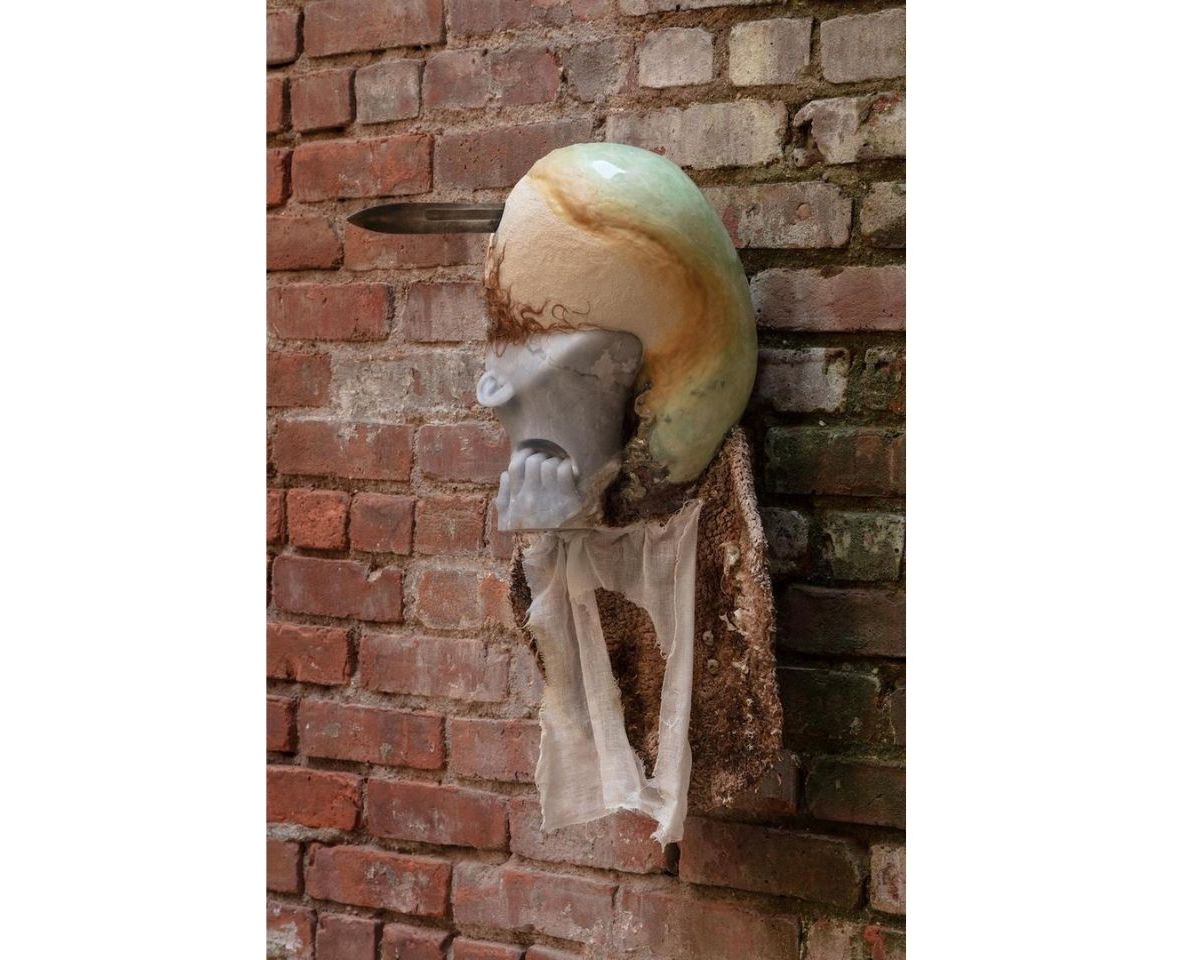

Pictured above, by Catalina Ouyang, from the exhibition cunt waifu:

doubt II (the thing itself and not the myth / what blood relation / turning horror into power / the sea that we carried for you / Do you not love us? ) 2020

hand-carved alabaster, M1905 bayonet, lime plaster, gypsum plaster, horse hair, faux fur, pigment, epoxy resin, beeswax, burned rug, gauze, sewing pins, rat bones

Notes

1 Christine Reiko Yano and Neal K. Adolph Akatsuka, Straight A’s: Asian American College Students in Their Own Words (Durham, NC: Duke UniversityPress, 2018), 41.

2 We invoke the queer erotic positioning top/bottom to challenge the presumed lack of agency assigned those who “bottom.” See Tan Hoang Nguyen, A View from the Bottom: Asian American Masculinity and Sexual Representation (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014), for a queer ofcolor revaluation of “bottoming.”

3 In important new work such as Sexual Citizens: A Landmark Study of Sex, Power, and Assault on Campus, an anthropologist and sociologist duo at Columbia University undertake to study sexual violence using an “eco-logical model” that allows them to view their subjects with the necessary complexity and empathy. “What kind of society,” they ask, “produces people whose sexual projects ignore the basic sexual citizenship of others?” But also: “What kind of society produces people whose feeling about their own right to sexual self-determination is so impoverished that they’d spare someone else an awkward interaction, even if it means having a strange and unwelcome penis inside of them?” See Jennifer S. Hirsch and Shamus Khan, Sexual Citizens: A Landmark Study of Sex, Power, and Assault on Campus (New York: W. W. Norton, 2020), 19. It is research we recommend as supplying some of what progressive feminism needs in its study of consent: an unblinking assessment of the social drivers and systems that make assault possible or even probable, as they condition decisions made even by those who wish neither to be victims nor perpetrators. Yet, even at an Ivy League site where Asian Americans make up the second-largest racial group, the study over-represents White subjects and offers no viable theories of race.

4 Amanda Su, “Three Stories and the Problem of Consent.”