The work of nine ekphrastic poets

March 3, 2015

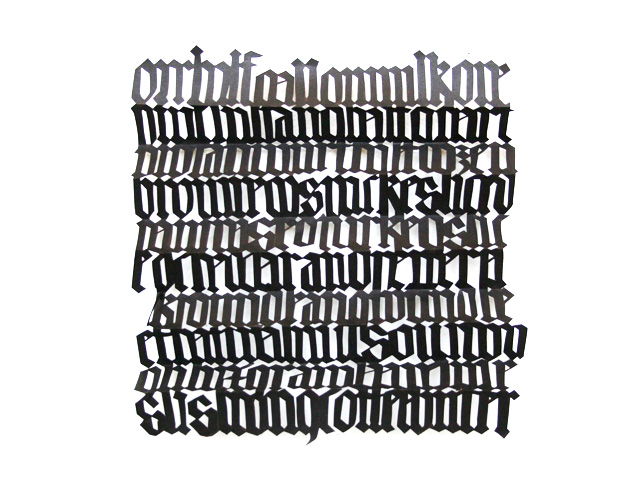

If not already visual artists themselves, the poets collected here have extremely close ties to the visual arts and visual culture, from painting to film to installation: they write about art, in both critical and creative modes, and collaborate widely with artists. It should be no surprise, then, that the diverse and vibrant work in this portfolio, some of which was specially commissioned for The Margins, often yokes text and image together in surprising ways and represents ekphrastic poetry in some of its most advanced and innovative forms. In fact, some of these pieces seem to exceed the genre of ekphrasis altogether; for example, Christine Wong Yap brings together sculpture and concrete poetry in Cloud to form a delightfully baroque thought balloon, highlighting the fact that language is, in her words, both “physical and immaterial.”

When engaging with the tradition of ekphrastic poetry, these poets frequently strive to go beyond, to quote Leo Spitzer’s classic definition, “the reproduction, through the medium of words, of sensuously perceptible objets d’art.” A case in point would be Eileen Tabios’ “Athena’s Diptych,” which, rather than reproducing a specific artwork, inventively “reproduces” the painterly technique of scumbling in a linguistic medium. In a 2003 review-essay called “Redeeming my Faith in Ekphrasis,” Tabios says, “I came to prefer [. . .] writing poems that, while inspired by and perhaps even seeking to mirror a visual image, actually came to embody something different.” Likewise, in his introduction to Viva la Difference: Poetry Inspired by the Painting of Peter Saul John Yau outlines the project’s allegiance to non-normative and anti-mainstream ekphrasis: “Our intention was different [. . .] Our intention was not to be impressionist or to tell a story. Those are well-known solutions, and, frankly we wanted something else.” Indeed, his “Further Adventures in Monochrome,” breaks from Simonides of Keos’s classical dictum of ekphrastic poetics, Poema pictura loquens, pictura poema silens [poetry is a speaking picture, painting a mute poetry], by giving voice not to some mute artifact, as John Keats famously does in “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” but to the painter Yves Klein; indeed, Yau might be torquing the term ekphrasis back to its etymological origin (“ek-” meaning “out” and “phrazein” meaning “to speak”) in that his rich, ventriloquizing monologue uncannily channels Klein’s voice “speaking out” from beyond the grave.

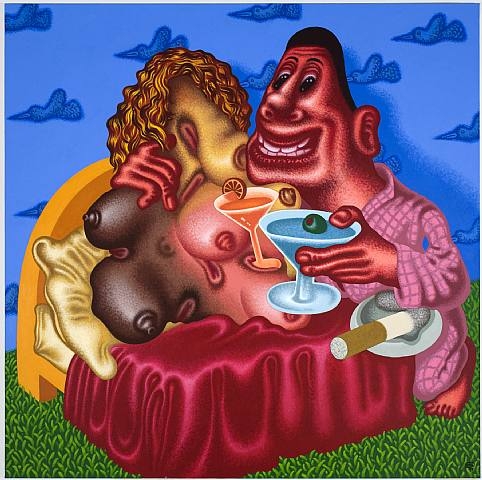

One common thread among these works is that the poets often eschew a sustained, even fetishizing, focus on the objet d’art, which is typical of many ekphrastic poems in the modern canon from Rainer Maria Rilke’s “Archaic Torso of Apollo” to Wallace Stevens’ “Anecdote of the Jar,” by widening their attention to include the artists’ words and elements from the artists’ everyday lives. Debora Kuan’s “How to Take Black-and-White Pictures” cites Diane Arbus’ journal through an intimate second-person address (“Your last journal entry reads: The Last Supper. / It wakes you. You want a floor to drag a doll over”) while Jennifer Hayashida’s “On Peter Saul (Laughter)” draws on Saul’s language from a 2008 interview. In the latter, the epigraph is a direct quotation from Saul, but we can also see how Hayashida appropriates and transmutes Saul’s first answer—”So-called ‘good painting’ is like a parade of intelligent thinkers. I’m glad to be outside of that. Call me a crackpot if you want”—into the beginning sentence of her poem: “Call me a crackpot in pajamas: I sit on a stump called painting and watch a parade of immodest thinkers march by.”

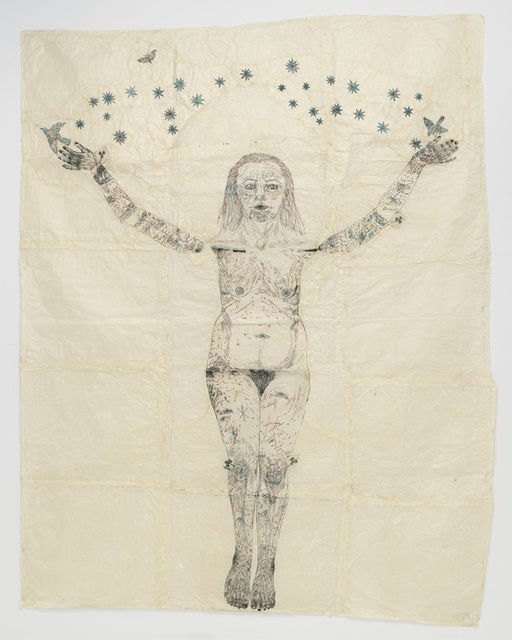

Mei-Mei Berssenbrugge’s “I Love Artists” begins not with a treatment of the figure of Kiki Smith (in the way that, say, W.H. Auden cites “The Old Masters” in “Musée des Beaux Arts”), but of Smith as an embodied and familiar presence: “I go to her house and talk with her as she draws me or knits, so it’s not one-on-one exactly, blue tattooed stars on her feet.” The importance of the star tattoos on Smith’s feet attests to Berssenbrugge’s micro-attention to detail and to subtle perceptual shifts; the poem’s fourth section, which alludes to Bruce Nauman’s Mapping the Studio, trains its gaze on seemingly unimportant phenomena that lurk on the fringes of our attention: moths, mice, “light reaching into corners of the room,” and “shadows of possessions that day by day absorb our energy.” In an interview with Laura Hinton, Berssenbrugge says, “To me visual art often expresses new ways of looking before they appear in poetry.”

In Walter K. Lew and O Woomi Chung’s “Moss” and “The RV Projects,” a pair of multimedia poems which document and extend the site-specific mobile projections and installations they executed around South and Central Florida, the visual object in question is not so much a fixed, centripetal focal point, like Stevens’ “jar in Tennessee,” but an elaborate, location-dependent ensemble that includes projector, projectionist, the vagaries of the surrounding environment as well as the images being projected. In these poems, which seem to offer a kind of playful alternative to Charles Olson’s “projective verse,” senses such as seeing and hearing are synaesthetically blurred and the terms “reflection” and “projection,” in all of their semantic complexity, are understood in dynamic relation in an effort “to shine / The project of reflection.”

As a (verbal) representation about (visual) representation, ekphrasis can offer a powerful self-reflexive consciousness, which the poets here take up with considerable cleverness. For example, we can read Shin Yu Pai’s “the great figure” as a kind of “meta-ekphrastic” poem as it points to not only Kent Barker’s black-and-white photograph but also to William Carlos Williams’ “reverse ekphrastic” piece (also named “The Great Figure”), which famously inspired Charles Demuth’s I Saw the Figure Five in Gold (1928). The “great figure,” in Pai’s poem, refers to the figure of ekphrasis itself as much as it does the figure “3” depicted in the photograph.

In a similar vein, Kuan suggests that her poem “Pastoral,” which nicely puns on the “felt” imagery from the German sculptor Joseph Beuys, “can be seen as an ekphrastic poem, although not one about any specific painting or work of visual art, rather about visual art itself.” In this sense, many of these pieces can be considered acts of creative art criticism or critical inquiries into the act of perceiving as well as poetry. And many, as I’ve been insisting, productively rub the genre of ekphrasis against the grain; as if in reaction to visual theorist W. J. T. Mitchell’s observation that “the treatment of the ekphrastic image as a female other is a commonplace in the genre [. . . which] tends to describe an object of visual pleasure and fascination from a masculine perspective,” Pai’s homophonic play in her title “Bell(e)” yokes together both the maker (Toshiko Takaezu) and the made object (her 1997 bell) and orients us toward a female subject rather than an othered, feminized object.

In “The Active Voice: 12 Poems on Contemporary Art,” a poetry and art portfolio from the June/July 2013 issue of Art in America, Raphael Rubinstein says, “[i]t’s a good moment… to once again listen to what poets may have to tell us about the art of our time.” I concur, and I want to suggest here that Asian American poets have a crucial place in that discussion. My sincerest thanks goes out to all of these wonderful contributors.

—Michael Leong

Christine Wong Yap

“Cloud”

Debora Kuan

“How to Take Black-and-White Pictures” | “How to Make Bells” | “Pastoral” | “TV Room”

Eileen Tabios

“Athena’s Diptych”

Jennifer Hayashida

“On Peter Saul (Laughter)”

Mei-Mei Berssenbrugge

“I Love Artists”

Shin Yu Pai

“Lunch Poem” | “After Toshiko Takaezu” | “Dear Juan” | “the great figure” | “prime”

Walter K. Lew and O Woomi Chung

“Moss” | “The RV Projects”

John Yau

“Further Adventures in Monochrome”

Christine Wong Yap

CLOUD

Cloud consists of dozens of phrases cut from copper sheets and suspended from black ropes and elastic thread. The illegible mass hovers overhead, a cloud-like shape defined by the black supports. The suspended words and untidy ropes hint at nagging thoughts or psychic garbage.

Cloud…present[s] language as physical and immaterial; as a messy failure; as nagging psychic garbage; and as the dialogue between lovers—banal as daily logistics, essential for our most meaningful utterances. If relationships are grounded in communication—and language’s flaws and fragility—we must take vigilant care of our words and their subtexts: in other words, reading beyond the legible.

Cloud… [is an] extension…of an ongoing project around ultimate meaning and quotidian reality. How do we make meaning in our lives, when so much of our daily activity consists of meaningless tasks of survival? How do we mean, when language is inadequate and communication relative?

is an interdisciplinary artist working in installations, sculptures, multiples, and works on paper to spark and sustain attention to emotional experiences. Her work has been exhibited extensively in the San Francisco Bay Area, as well as in New York, Los Angeles, Manila, Osaka, Poland, London, Newcastle, and Manchester (U.K). A longtime resident of Oakland, CA, she relocated to New York, NY in 2010.

Debora Kuan

HOW TO TAKE BLACK-AND-WHITE PICTURES

1

Imagine a painted door. Owl eyes. A tiny blue egg

arranged on a ladder with other birds’ eggs.

Rat bells, as in, You hear rat bells all along the wall.

It helps you. You get some sleep in the bathtub,

draw a horse-head with a soapy finger. It dissolves. Two sun streaks.

You are the maid-of-honor, you are the private equestrian.

What you like. Rained-out appointments. A tall carafe.

Card-games and hand-me-down sweaters.

Imagine a house packed with jacks. Dishes piled, a man-servant.

Snapshot. Your last journal entry reads: The Last Supper.

It wakes you. You want a floor to drag a doll over.

An armoire. A barrel of tar. The heaviest thing will do.

2

Imagine owl eyes, all along the wall. A colored egg

hidden in the fireplace. A sunburn. You step into a painted hole.

Mothballs, as in, A bee-shaped jewel you keep in mothballs.

It alarms you. You get some sleep in the dentist’s chair, dream

of a pair of saints. They drag their feet. Two ice-cubes.

You are the state senator, you are the private doll-maker.

What you like. Apothecaries. Seven-layer cakes.

A set of flattened spoons. It helps you.

Imagine a fur shop packed with rats. A window dressing. An itch.

You switch cameras. Your first journal entry reads:

Found a frozen blue jay on the front step today. It reminds you.

You want a sea to toss sandbags over. A door-stop

of cat’s-eye marbles. A dead motor. The steadiest thing will do.

[Note: The last entry of Diane Arbus’ diary reads, “The Last Supper.”]

(from Xing. 2011. Saturnalia Books. Ardmore, PA.)

HOW TO MAKE BELLS

Maybe it is the epoch of strange jesters, their faces caked in make-up. A cortege of chewed plum pits placed across the table. You don’t ask. You erase a part of the recording by mistake. You get chased. You still get distracted by these engravings of toothless saints, haloed in sulfur and pith.

You wake up every morning reciting the three holy virtues. Or they recite you. It doesn’t matter. Your search for clay isn’t discouraged by a sudden rainstorm. You keep on, hunting for a particular stain and the scent of hailstone, something that can slide off metal. You think, This will be the mold that holds it, this will be the matter.

Steeped in a pool of red light, one of your horses rolls over and struggles to stand. It steadies itself. It gallops off the frame. Then the real repeats. Faith. You concentrate on the fricative. You remember how you got here.

(from Xing. 2011. Saturnalia Books. Ardmore, PA.)

PASTORAL

This is the map of stationary cloud and crow.

Felt bird perched

atop felt world at last,

while the white colts crowd around.

And, in his wagon, Lin sits still,

pulls on his hand-me-down black boots.

Left foot, right foot. All roads end

in spools of pink, then fasten to other roads.

This is the map, and this is its legend.

In far-left field, the cemetery

pinwheels languish in non-spin.

Unshiver, atremor.

The quiet corruptions feel several.

Nameless headstones, loose teeth.

A hand inside a stopped watch,

which cannot feel its gears.

Chao begins another story, the one

about the opaque form

against its opaque field.

Another manifestation of owl.

We go the only way we can: brick by brick,

drum by drum.

We wonder at the flatness of travel, and how

beneath us, against us,

another thing fattens.

So this is exile, this is flight.

Women crossing the landscape in droves,

dropping silverware, gold

heirlooms, hair.

The good hand aids the mangled one.

We doctor. We hold our tongues

and check our mouths for sores.

At night, we wrap a pear in long woolen underwear

and wait for our arrival.

ON PASTORAL

The world of this poem grew from a simple wish to play on the word “felt.” I like the fact that the word houses both the material and the act of feeling (or the act of having felt). Also, at the time I wrote the poem, I was very interested in Joseph Beuys’s work and was learning about his symbolic interest in materials like felt and wax. The hand that cannot feel the watch’s gears in the second stanza translates onto the body Beuys’ piano wrapped in felt: both are manifestations of inefficacy and handicap, frustration and impossibility.

The rest of the poem too can be seen as an ekphrastic poem, although not one about any specific painting or work of visual art, rather about visual art itself. Chao’s story turns out to be not much of a narrative at all. It is instead about the concept of figure and ground: “the opaque form/ against its opaque field.” And everywhere, things are in a state of “non-spin.” They are still, stationary, or flat, even travel itself. I intend that elegiac torpor not just as futility but also as permanence: A work of art is a creation that can outlast you—at least, we hope so in the best of circumstances…

(from “In Their Own Words,” http://www.poetrysociety.org/psa/poetry/crossroads/own_words/page_17/)

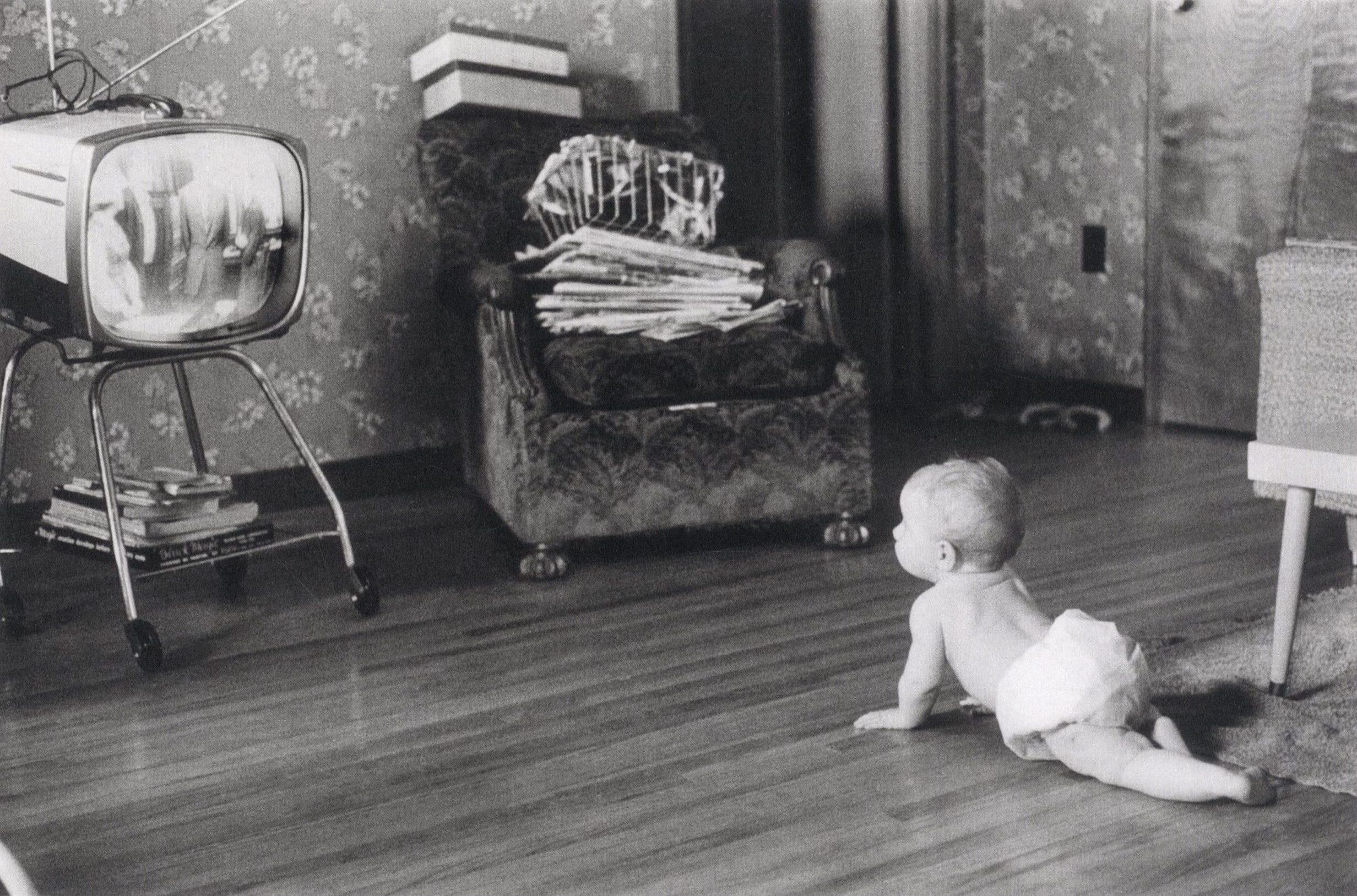

TV ROOM

after Garry Winogrand

Steroid orange flowers paper a room

and speak to me

from the bleached-white faces of TV personalities.

They make a scene

that throbs at a wooden distance,

that could topple like so many boxes.

The furniture of the horizon:

cattle asleep in softnesses.

I have crawled their backs and wept

in their wire baskets

for you—of course, for you.

I couldn’t see you, but you were there,

on another hill, your glass of ice

clinking like delicate laughter.

You didn’t leave me.

You wouldn’t have left me for the world,

but how could I have known?

is the author of XING, her debut poetry collection (Saturnalia Books, 2011). A two-time Pushcart nominee, she has been awarded a Fulbright creative writing fellowship (Taiwan), University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop Graduate Merit Fellowship, Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference work-study scholarship, and residencies at Yaddo, Macdowell, and the Santa Fe Art Institute. Her short fiction and poems have appeared or are forthcoming in American Letters and Commentary, Atlas Review, The Awl, The Baffler, Boston Review, Brooklyn Rail, Fence, Gigantic, Glittermob, HTMLGiant, Hyperallergic, Indiana Review, New American Writing, Pleiades, The Iowa Review, The L Magazine, The Rumpus, and other journals. She has also written about contemporary art, books, and film for numerous publications. She is currently a director of English Language Arts assessment at the College Board and a senior editor at Brooklyn Arts Press.

Eileen Tabios

FROM “NOTES ON DREDGING FOR ATLANTIS”

These are ekphrastic poems utilizing the painterly technique of scumbling. From Merriam-Webster Dictionary:

scumble \SKUM-bul\ verb

1 a : to make (as color or a painting) less brilliant by covering with a thin coat of opaque or semiopaque color b : to apply (a color) in this manner

*2 : to soften the lines or colors of (a drawing) by rubbing lightly

The history of “scumble” is blurry, but the word is thought to be related to the verb “scum,” an obsolete form of “skim” (meaning “to pass lightly over”). Scumbling, as first perfected by artists such as Titian, involves passing dry, opaque coats of oil paint over a tinted background to create subtle tones and shadows. But although the painting technique dates to the 16th century, use of the word “scumble” is only known to have begun in the late 18th century. The more generalized “smudge” or “smear” sense appeared even later, in the mid-1800s.

![Gustav Klimt, Pallas Athene, 1898, Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien, Vienna [in the public domain: http://www.wikipaintings.org/en/gustav-klimt/minerva-or-pallas-athena]](https://aaww.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/1024px-Klimt_-_Pallas_Athene.jpg)

Gustav Klimt, Pallas Athene, 1898, Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien, Vienna.

ATHENA’S DIPTYCH

“Athena Begins”

My love. If

words can

reach

whatever world you

suffer in—

Listen:

I have things

to tell

you.

At this muffled

end to

another

year, I prowl

somber streets

holding

you—in my

head, this

violence!—

a violent gaze.

You. With

dusk

arrives rain drifting

aslant like

premature

memory. Am I

the one

who

suddenly cleared these

streets? My

Love,

all our hours

are curfew

hours—

what I offer

is this

dying

fish into whose

gullet I

have

thrust my thumb.

Why did

you

lose all Alleluias?

My love—

Listen:

“Athena”

What’s deemed necessary

changes. Hear

me

listening in another

decade, editing

last

and first lines.

A different

Singer

croons from behind

an impassive

speaker.

I listen, cross

out more

lines.

The poem cannot

be pure.

Sound

never travels unimpeded

by anonymous

butterflies.

Writing it down

merely freezes

flight—

Translation: an inevitable

fall. Take

control

by shooting it

as if

pigeons

were clay: This

one is.

But

it provided pleasure

once, was

“necessary.”

Once, it flew

with non-imaginary

wings.

O, clay pigeon.

Translation: the

error

is my ear’s.

The sky

ruptured

suddenly—I saw

but did

not

hear the precursor

fall of

leaves.

*****

Edit it down.

Edit it

down.

Silence is Queen,

not lady

-in-waiting.

Edit it down.

Edit it.

Edit

it down. Edit

it. Edit.

Edit.

[Note: These poems scumble from John Banville’s novel, Athena (Vintage Books, New York, 1995).]

(from Dredging from Atlantis. 2006. Otoliths. Rockhampton, Australia.)

loves books, and has released more than 20 print, five electronic, and one CD poetry collections; an art essay collection; a “collected novels” book; a poetry essay/interview anthology; a short story collection; and an experimental biography. Her most recent release is SUN STIGMATA (Sculpture Poems) (2014). Forthcoming in 2015 are two poetry collections, I FORGOT LIGHT BURNS and INVENT(S)TORY, a Selected List Poem collection, as well as a criticism/biography book, AGAINST MISANTHROPY: A LIFE IN POETRY (2015-1998). She has also exhibited visual art and visual poetry in the United States and Asia. Recipient of the Philippines’ National Book Award for Poetry for her first poetry collection, she has crafted an award-winning body of work that is unique for melding ekphrasis with transcolonialism. More information is available at http://eileenrtabios.com.

Jennifer Hayashida

ON PETER SAUL (LAUGHTER)

“It had never occurred to me that viewers would want less to look at.”

PETER SAUL

Call me a crackpot in pajamas: I sit on a stump called painting and watch a parade of immodest thinkers march by. They send each other pictures in a can and their pictures have no problems. They reap rewards for their guaranteed techniques.

I look for the racist and sexist ones. Collect an abundance of private parts, lips to tips and teets to teeth, scour museums of calm technical problems, take away the spectators’ upper hand when they want different ways to paint a certain white.

Minimalism takes painting away and gives it back like a transcript of silence. Give me paintings like photos of brains blown out, more than just a tangle of arms and legs. Don’t give me a C for this painting: I’ll be drafted.

There is no woman here, only assorted pieces of anatomy, slick like hot dogs or wet balloons. Like sex between celebrities in a heavy gilded frame. Sometimes a hot dog can be more delicious than the beef it comes from. We need a bit of harm for our own good.

(from Viva la Difference: Poetry Inspired by the Painting of Peter Saul. 2010. Off the Park Press. New York, NY.)

is a poet, translator and visual artist who was born in Oakland, CA, and grew up in the suburbs of Stockholm and San Francisco. She received her B.A. in American Studies from the University of California at Berkeley, and completed her M.F.A. in poetry from the Milton Avery Graduate School of the Arts at Bard College. She is the recipient of awards from, among others, the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, the New York Foundation for the Arts, PEN, the Witter Bynner Poetry Foundation, the Jerome Foundation, and the MacDowell Colony. She is the translator of Fredrik Nyberg’s A Different Practice (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2007), and Eva Sjödin’s Inner China (Litmus Press, 2005) with translations of Ida Börjel, Karl Larsson, and Athena Farrokhzad forthcoming. Her poetry and translations have been published in journals such as Salt Hill, Chicago Review, and Circumference, while her collaborations in film/video have been exhibited in the U.S. and abroad.

Mei-Mei Berssenbrugge

I LOVE ARTISTS

1

I go to her house and talk with her as she draws me or knits, so it’s not one-on-one exactly, blue tattooed stars on her feet.

I pull the knitted garment over my head to my ankles.

Even if a detail resists all significance or function, it’s not useless, precisely.

I describe what could happen, what a person probably or possibly does in a situation.

Nothing prevents what happens from according with what’s probably, necessary.

2.

Telling was engendered in my body and fell upon me, like a battle skimming across combatants, a bird hovering.

Beautiful friends stopped dressing; there was war.

I’d weep, then suddenly feel joy and sing loud words from another language, not knowing my song’s end.

I saw through an event and its light shone through me.

Before, indifference was: black nothingness, that indeterminate animal in which everything is dissolved; and white nothingness, calm surface of floating, unconnected determinations.

Imagine something, which distinguishes itself, yet that from which it distinguishes does not distinguish itself from it.

Lightning distinguishes itself from black sky, but trails behind, as if distinguishing itself from what espouses it.

When ground rises to the surface, her form decomposes in this mirror in which determination and the indeterminate combine.

Did you know, finally, there was not communication between her and myself?

Communication was in time and space that were coming anyway.

I may suffer if I can’t tell the agony of a poisoned rat, as if I were biting.

3.

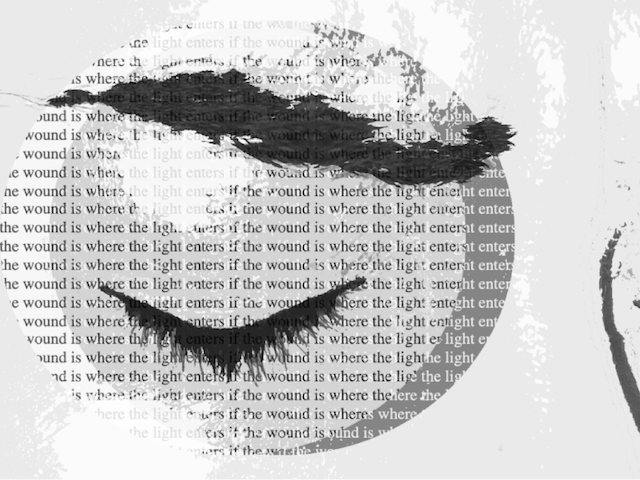

Bruce leaving for the night makes space for his cat to enter.

Mouse (left) exits door and returns

Moth and mouse on sculpture exit (left), noise.

It’s an exterior relation, like a conducting wire, light fragment by fragment.

I realize my seeing is influenced by him, for example, when we change form and become light reaching into corners of the room.

Even now, we’re slipping into shadows of possessions that day by day absorb our energy.

I left my camera on to map unfinished work with shimmering paths of my cat (now disappeared), mice and moths (now dead).

There’s space in a cat walking across the room, like pages in a flip-book.

The gaps create a reservoir in which I diffuse my embarrassment at emotion for animals.

I posted frames each week, then packed them into suitcases, the white cat and her shadow, a black cat.

I named her Watteau, who imbues with the transitory friendship we saw as enduring space in a forest.

4.

A level of meaning can be the same as a place.

Then you move to your destination or person along that plane.

Arriving doesn’t occur from one point to the next.

It’s the difference in potential, a throw of dice, which necessarily wins, since charm as of her handcrafted gift affirms chance.

I laugh when things coming together by chance seem planned.

You move to abandon time brackets, water you slip into, what could bring a sliding sound of the perimeter of a stone?

You retain “early” and “walking” as him in space.

When a man becomes an animal, with no resemblance between them, it feels tender.

When a story is disrupted by analyzing too much, elements can be used by a witch’s need for disharmony.

Creation is endless.

Your need would be as if you were a white animal pulling yourself into a tree in winter, and your tears draw a line on the snow.

![Bruce Nauman. “Mapping the Studio 1 (Fat Chance John Cage).” 2001. Dia Art Foundation. [represented by Sperone Westwater - http://www.speronewestwater.com/cgi-bin/iowa/contact/index.html]](https://aaww.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Bruce-Nauman-Mapping-the-Studio-I-Fat-Chance-John-Cage-2001.jpg)

was born in Beijing and grew up in Massachusetts. She is the author of 12 books of poetry, including Empathy, Four Year Old Girl, I Love Artists: New and Selected Poems, and Hello, the Roses. She has collaborated with many artists, including Kiki Smith and her husband, Richard Tuttle. She lives in northern New Mexico and New York City.

Shin Yu Pai

LUNCH POEM

(after Subodh Gupta)

6,000,000

to one: the delivery that

goes missing – a lunch pail that fails

to arrive @ its destination; domestic

articles bear homemade offerings produced

by housewives & dadi jis for their men-folk –

fleet-footed dabbawallas dispatch, carry,

& collect steel boxes by the thousands packed

lunch boys sport starched cotton nehru

caps pilot familiar passages – the son

of a railway guard solders stainless-steel

tiffin carriers a new class

of metalwork

![Toshiko Takaezu. Bell (1997). Seattle's Volunteer Park Conservatory. [Courtesy Myra/Flickr - https://www.flickr.com/photos/mylin/2677995497/]](https://aaww.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/bell.jpg)

Toshiko Takaezu. Bell (1997). Seattle’s Volunteer Park Conservatory. Photo courtesy Myra/Flickr.

BELL(E)

After Toshiko Takaezu

in centuries

past, sunk

beneath soil

to draw earth’s

vital force, inert

vessel of

sound + light,

conserved

in a museum

of curative plants

the moment of

stillness &

gathering before

the shudder

of first sound

dreaming

the shake of chime

hum &

g o n g

(from Adamantine. 2010. White Pine Press. Buffalo, NY.)

Shin Yu with photographer Kent Barker

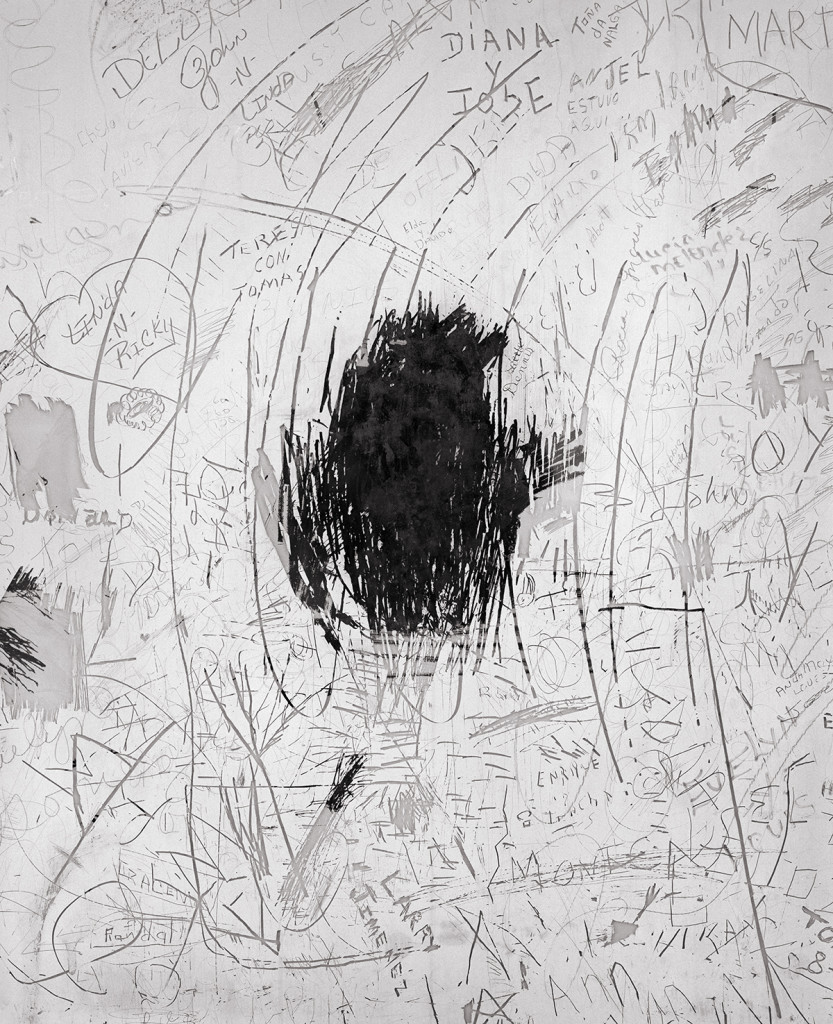

Dear Juan

here was Enrique

here was Monica

here was Diana

estuvo aqui

here was Larry

here was Lucia

here was Marta

Teresa con Tomas

John and Linda

logged in the same hand

as “Linda -N- Ricky”

inscribed inside a heart

the tags of former

lovers scraped & abraded

the great figure

(after William Carlos Williams)

Among the lights

and rain

I saw the figure 3

in gold on wet

asphalt

yellow stripes

dividing lines

between boarders

wheels rumbling back

to a flat, through

the glaring town

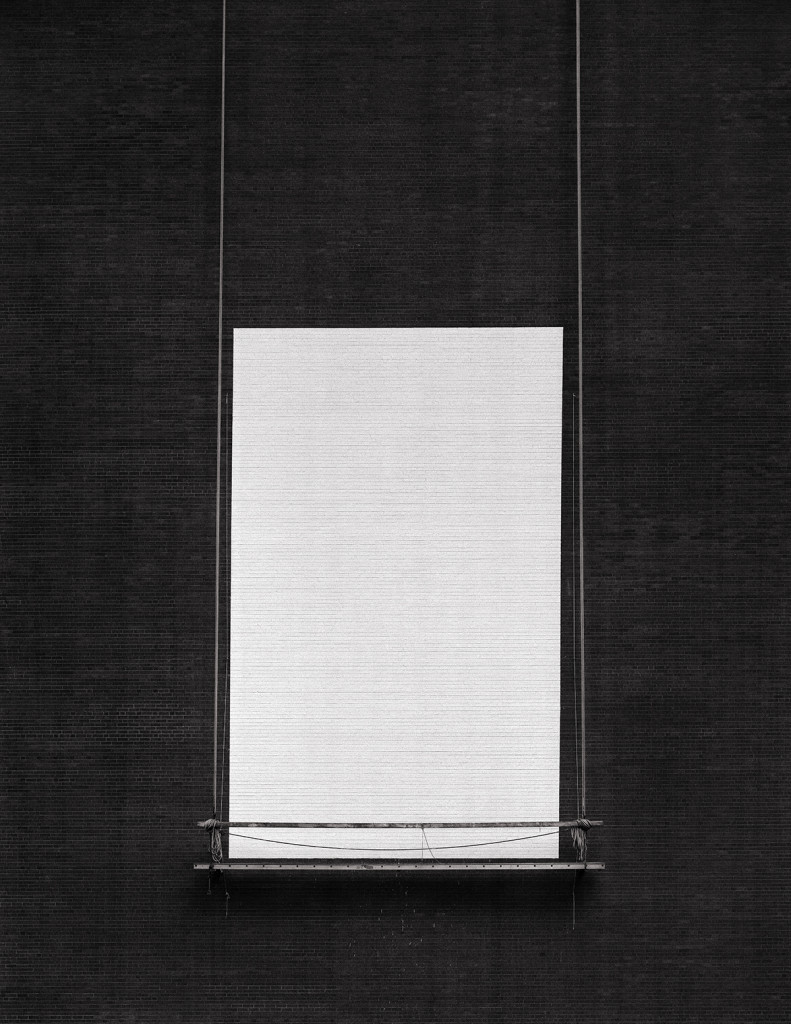

prime

scaffold set: brick wall,

bosun’s chair –

rope swing props

up an uncolored field –

the white backdrop

before beginning

(Previously unpublished poems)

is the author of several poetry collections including AUX ARCS (La Alameda, 2013), Adamantine (White Pine, 2010), Sightings (1913 Press, 2008), and Equivalence (La Alameda, 2003). Her limited edition artist book projects include Hybrid Land (Filter Press, 2011) and Works on Paper (Convivio Bookworks, 2007). A former writer-in-residence for the Seattle Art Museum, her poems have been commissioned twice by the Dallas Museum of Art. She holds an MFA from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago and an MA in Museology from the University of Washington. For more info, visit http://shinyupai.com.

Walter K. Lew and O Woomi Chung

MOSS

Afraid that you’d hear me pee, I squeezed muscles I didn’t know I had. Afraid also of embarrassing you, I pretended not to hear you pee. But you just asked: “How come you don’t poo?”

Today, two years later, you tell me from the most faraway place – that seeing trees shiver in the wind reminded you of the sound of me peeing.

Dew collecting in fissures that won’t seal – when I hear it, I begin to clear. The vague moistness and my tongue curl around each other.

Sipping the afternoon away with you, I’m not sure what’s left of the day.

If I summon the taste of you that always sits behind my tongue,

If I match frequencies with you and emit the sound of my peeing,

THE RV PROJECTS

I used to believe not listening to myself would make me resilient, but it was only a trick, like covering the sky with my palm.

1.

Whether I was headed into corners or out no longer seemed

From that on it would always be the same moment

Death is great

long lived death

I had no reason to believe but the opposite

Had blocked things so long I felt it would be good

To switch ideas the book and start moving again

2.

Camera, projector even hand-held:

These were clearly different modes, like entendre/dire,

Input/output or perception/behavior––distinctions deeper

Than mere paired

splayings of area

An above & below a left & right

But every cell that receives light projects it to others,

burning in response,

And speech loses its path without self-listening.

Gesture is guided not only by the hand’s

Breathing of the air, but foreseen signs

Of how it is taken.

3.

We’ve always worshipped mirrors,

But windows allow us both

To see ourselves, a past

in the immediate glimmer

And send through.

We make a shift and dappling

Screen of our eyes (scrim to the arrays

behind them) to shine

The project of reflection.

The photographs in “Moss” and “The RV Projects” are from documentation of “RV Project,” a series of site-specific mobile projections and installations by Walter K. Lew and O Woomi Chung.

’s books include Treadwinds: Poems and Intermedia Texts, winner of the Asian American Writers’ Workshop’s Annual Literary Award and finalist for the Pen Center USA poetry award (2003) andExcerpts from: ∆IKTH 딕테/딕티 DIKTE, for DICTEE, the first book on the work of Theresa Hak Kyung Cha. He edited Crazy Melon and Chinese Apple: The Poems of Frances Chung, Kôri: The Beacon Anthology of Korean American Fiction, coedited with Heinz Insu Fenkl, and the anthologies Premonitions: The Kaya Anthology of New Asian North American Poetry and Muae 1, both from Kaya, of which Lew was the founding chief editor. Lew’s latest volume is Imperatives of Culture: Selected Essays on Korean History, Literature, and Society from the Japanese Colonial Era, coedited with Christopher Hanscom and Youngju Ryu. His translations and scholarship on Asian American and Korean culture have appeared in many collections, and he is a coeditor of The Yi Sang Review (Seoul). Lew’s multimedia “movietelling” pieces, sometimes co-created with filmmaker Lewis Klahr, have been staged since the early 1980s for numerous international arts and film festivals. Splitting his time between Sunnyside, Queens and Miami, Lew’s work over the last few years has focused on outdoor multimedia performances, artist’s books, and mobile projection from his RV.

is a multimedia visual artist. Born in South Korea, she is currently pursuing her MFA at School of Visual Arts, New York. O mainly works with video and drawing, as well as photograph, installation, and performance. Before coming to NY, she worked on several films and musicals as production designer, stage designer, and lighting director. The films include Ki-duk Kim’s Moebius (2013) and Deborah Kim’s KIN (2013), and the musicals include Soulmate (2009) and Madical (2008) at Ewha Womans University, Seoul, S. Korea. She also has contributed a couple of essays to Nabulnabul, an independent quarterly magazine in S. Korea and recently self-published Scrota (2014).

John Yau

![Yves Klein. Silence is Golden (1960) [credit line - © Yves Klein, ADAGP, Paris]](https://aaww.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/yves-klein-e2809cle-silence-est-d_ore2809d-silence-is-golden-1960.jpg)

FROM “FURTHER ADVENTURES IN MONOCHROME”

4)

I dwell in possibility, Emily Dickinson

I dwell in impossibility, Yves Klein

You should understand that I did not want you to read a painting. I wanted you to bathe in it before words domesticated the experience, and you turned to such stand-bys as “illumination” and “transcendent” to describe what happened to you. Painting should not be sentenced to sentences.

Painting is COLOR, I yelled at my first champion and biggest supporter. COLOR banishes words from its domain. When you read a painting, you turn it into language, but there is so much that cannot be turned into language that each of us experiences every day.

Red shadows leak out of rusting cars and collapsed bridges.

Green smoke rises from behind horizons and rooftops.

The spectrum of your mother’s voice the last time she spoke to you.

Every day there are thresholds that you must cross to reach the domain where words mar every transmission, rendering them intangible. We put our memory of these reverberations aside in favor of what is known and, we believe, knowable. We say we are going to the beach and we will look at the ocean and leave indentations in the sand, but that is not what happens. We go there to ponder a blue parcel cut from infinity.

True poets and artists know where language ends, which is why they go there. Some settle for going beyond the possible into possibility, but others want to dwell in the impossible. I am not talking fantasy here, because that version of the impossible is just a story about a girl named Thumbelina or a boy named Jack. The ones who go to where two roads diverge in a yellow wood are not poets, because they believe that experience can be reduced to a lesson about choices. True poets know that language is neither window nor mirror. The mistake is to believe that the opposite is true, that words (or signs) are arbitrary.

This is my example of why words are not arbitrary. Charles Baudelaire believed that there are perfumes for which all matter is porous. These perfumes can permeate the air of one’s dreams. Our thoughts quiver in the shadows that fall over us; they begin to free their wings and rise in flight, tinged with azure, glazed with rose, spangled with gold.

Azure, Rose, Gold.

I was not thinking of Baudelaire when I made my paintings, but the poet was clearly dreaming of me when he sat at his desk and wrote “The Perfume Flask.”

Can’t you see that this is how I, radiating outward, happened to appear on this planet, this speck of dust? Yves Klein was born because Baudelaire predicted this propitious event by naming colors, which, like all colors, escape the confines of their names, becoming more than an emanation of infinity. Even black can get away from its name, which is why Malevich had to surround it with white. But what is color that isn’t surrounded by another color? What is that boundless world we catch a glimpse of whenever we look up at the sky? Is it so vast that we must turn away from it, afraid that it will swallow us up, which it will? Astronomy, the Greeks believed, was a royal science, which means I am a royal painter. Do not confuse me, however, with a painter of royalty, with Ingres, who used lines to hold and improve the faces of his sitters, who believed in the despotic power of beauty.

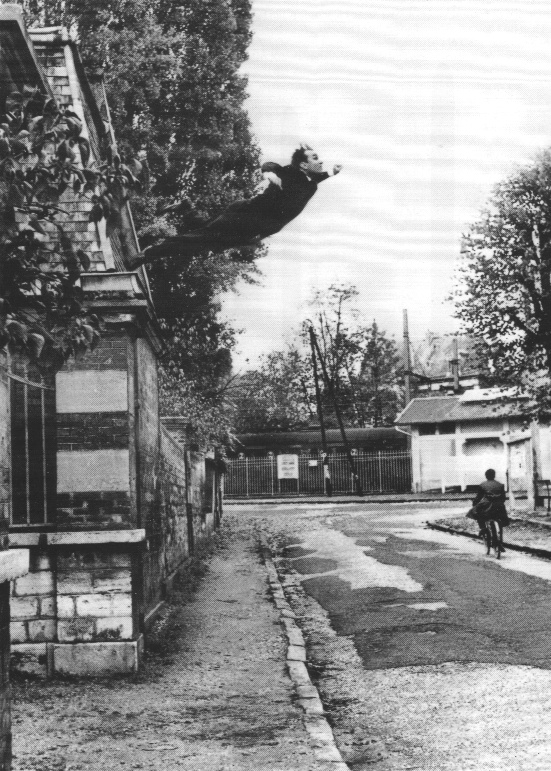

I am not interested in beauty. I am not Andy Warhol. He longed for possibility, but was afraid of what it might tell him. I dwell in impossibility, and I want to be embraced by what it will tell me. My name is Yves Klein. There is a photograph of me that you might know. I have put on my best suit and jumped out a window. My arms are outspread, but they are not wings. I don’t need them to fly. Nor am I the prince of clouds, Baudelaire’s albatross, fallen from the sky. Screw that fascist Marinetti. My arms are not the wings of a drunkard beating against the wall. Mine are the outstretched arms of a diver. I fall effortlessly through the air, but I never am completely fallen. The cobblestones and I will never meet. I hover in a miracle, which is why you believe in the photograph, even after you have learned how I tricked you. It wasn’t that hard to do. The true magician shows everyone how the trick was done, and after seeing how you were deceived, you believe in the trick all the more. I jumped out the window and I stayed in the air, which is where you wanted me to stay. I dwell in impossibility—that zone that lies beyond here and there, while embracing both.

(from Further Adventures in Monochrome. 2012. Copper Canyon Press)

is a poet, fiction writer, critic, publisher of Black Square Editions, and freelance curator. His recent books include A Thing Among Things: The Art of Jasper Johns and Further Adventures in Monochrome. His reviews have appeared in Artforum, Art in America, Art News, Bookforum, and the Los Angeles Times. He was the Arts Editor for the Brooklyn Rail (2006 – 2011). In January 2012, he started the online magazine, Hyperallergic Weekend, with three other writers. In 1996, he curated Ed Moses: A Retrospective of Paintings and Drawings for the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. In 2010, he helped organize Oil and Water for Stephen Harvey Fine Art Projects. In 2012, he organized Broken/Window/Plane for Tracy Williams, New York City. He has collaborated with many artists, including Norman Bluhm, Ed Paschke, Peter Saul, Pat Steir, Jürgen Partenheimer, Norbert Prangenberg, Squeak Carnwath, Thomas Nozkowski, Max Gimblett, and Richard Tuttle. He has received prestigious grants and fellowships for his poetry, fiction. In 2002, he was named a Chevalier in the Order of Arts and Letters by the French government. He is an Associate Professor in Critical Studies in the Mason Gross School of the Arts, Rutgers University.