Orhan Pamuk and Mo Yan, Noble Prize winners in Literature, were both writers-in-residence at the prestigious International Writing Program. An interview with IWP’s current director about one of the program’s founders, the remarkable Chinese novelist Hualing Nieh.

November 9, 2012

This interview originally appeared on the Asia Society’s Asia Blog.

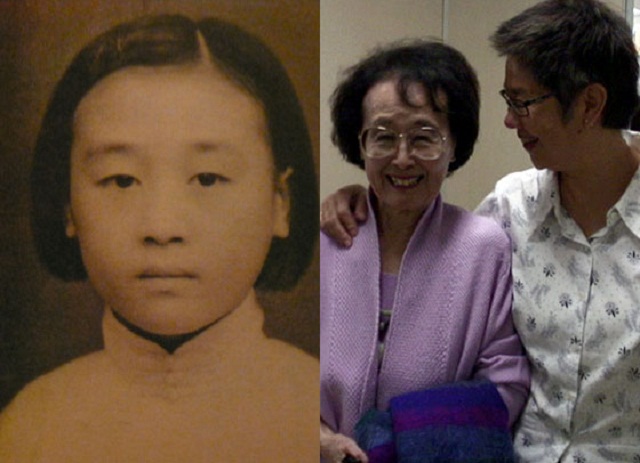

Angie Chen’s 2012 documentary One Tree Three Lives documents the remarkable life story of Chinese novelist and essayist Hualing Nieh, who endured civil war in China and political repression in Taiwan before eventually settling in the United States, where she helped found the prestigious International Writing Program (IWP) with her husband, the late American poet Paul Engle.

The film conveys the force of Nieh’s intellect and personality while also documenting how she and Engle were able to build the IWP into a major residency for literary figures from around the world. Among the program’s many other accomplishments, it was one of the first to host Chinese writers in the US after the resumption of diplomatic relations in the 1970s, and in more recent years it has counted two Nobel Laureates in Literature—Turkey’s Orhan Pamuk (2006) and China’s Mo Yan (2012)—among its participants.

In partnership with the International Writing Program, Asia Society New York will present One Tree Three Lives this Saturday, November 10, at 6:00 pm. After the screening, Nieh (appearing via Skype) and filmmaker Chen will be joined on stage for a discussion by Christopher Merrill, the IWP’s current director and the author of four volumes of poetry and five works of nonfiction.

Asia Blog’s Jeff Tompkins reached out to Merrill via email ahead of his New York appearance to talk about Hualing Nieh and the International Writing Program.

Jeff Tompkins: One Tree Three Lives suggests that Hualing Nieh and Paul Engle conceived of the IWP as a kind of trans-national space where writers could meet and engage with one another, outside of or above politics. How does the organization nurture a similar environment today? Were there particular challenges in the post-9/11 world, for instance?

Christopher Merrill: Our mission remains the same: to provide enough space and time for gifted writers from around the world to engage in a conversation about all manner of things, from favorite books and music to politics and cuisine. I tell them on the first day of the residency that they should make writing their priority, and while many do complete books during their stay some use their time to absorb the intensely literary atmosphere of Iowa City, which in 2008 was designated as the first, and only, UNESCO City of Literature in this hemisphere.

This fall we hosted 31 writers from 28 countries, each of whom brought to the table their unique literary sensibility, and that made for a robust conversation—what a colleague likes to call our three-month-long performance piece.

The documentary gives the impression that bringing in writers from both mainland China and Taiwan was a particular concern for Nieh and Engle. Do you sense that Hualing’s reputation is still a draw for the next, or emerging, generation of Chinese writers?

The documentary gives the impression that bringing in writers from both mainland China and Taiwan was a particular concern for Nieh and Engle. Do you sense that Hualing’s reputation is still a draw for the next, or emerging, generation of Chinese writers?

Hualing remains actively involved in recruiting the best Chinese writers to the IWP; in my time, thanks to her, we have hosted Mo Yan, Xi Chuan, Li Rui, Su Tong, Yu Hua, Chi Zijian, Meng Jing-hui, Liu Heng, Jin Renshun, Ge Fei, Bi Feiyu, and Zhang Yueran, to name a few. Hualing is revered in Chinese literary circles—and rightly so. What she has contributed to world literature, in terms of the IWP and her ongoing efforts to foster dialogue among Chinese writers from the mainland, Taiwan, and Hong Kong, is an incalculable good.

It’s impressive to learn that two of the most recent Nobel Prize winners in Literature, Orhan Pamuk and Mo Yan, were both writers-in-residence at the IWP. Did you have any personal experience with either author, and do you know if either of them interacted with Nieh?

Orhan Pamuk was in residence during Hualing’s tenure, and I gather that he spent most of his time writing The Black Book, which is regarded as his breakthrough novel.

Mo Yan came to the IWP in 2004, and he impressed me as a brilliant writer and a sweet man. In one email to Hualing after he won the Nobel Prize he said that she was his literary mother; in a follow-up message she learned that a wealthy businessman in China had offered Mo Yan a mansion in celebration of his Nobel Prize. His father rejected it: “No! No! No mansion. My son comes from a peasant family. He won’t take anything he didn’t earn with his labor.”

Those of us on the outside of the institution might be curious to know if or how the IWP is related to the equally venerated Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Do they have a complementary relationship? Is there much back-and-forth between the respective faculties, writers-in-residence, and student populations?

The IWP grew out of the Writers’ Workshop, which Paul Engle directed for nearly a quarter of a century before he and Hualing founded the IWP. The two programs occupy a pair of old houses across the street from each other, my staff includes a number of Workshop graduates, and during the fall residency the graduate students and visiting writers interact in a variety of ways—in our translation workshop, in joint readings, in the local watering holes. I spend a fair amount of time trying to figure out ways to interest students in what might be happening outside the precincts of American letters—in world literature, that is, some of the best of which is on display in the IWP.

One Tree Three Lives screens at the Asia Society this Saturday, November 10, at 6:00pm.