In the Texas prison system, my name is Chino. You will not know who I am unless you are immediate family or one of my few friends.

February 20, 2020

for my friend Thao

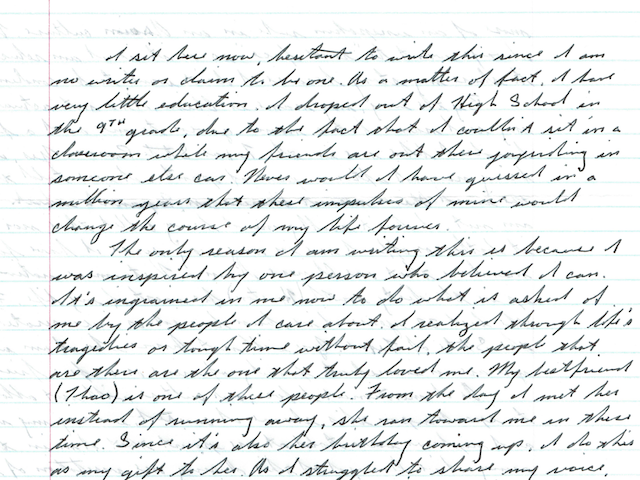

I sit here now, hesitant to write this since I am no writer and do not claim to be one. As a matter of fact, I have very little education. I dropped out of high school in the ninth grade, due to the fact that I couldn’t sit in a classroom while my friends were out there joyriding in someone else’s car. Never would I have guessed in a million years that these impulses of mine would change the course of my life forever.

The only reason I am writing this is that I was inspired by one person who believed I can. It’s ingrained in me now to do what is asked of me by the people I care about. I realized through life’s tragedies or tough times, without fail, the people who are there are the ones that truly loved me. My best friend Thao is one of those people. From the day I met her, instead of running away, she ran toward me. Since it’s also her birthday coming up, I do this as my gift to her. I struggle to share my voice, my experiences, and my perspective of things. Please understand that it’s a very difficult thing for me to voice.

As an Asian, I was taught at an early age to never speak about the bad things or the pain or the suffering in our families and loved ones. I remember one incident. While growing up, we had two rabbits. Coming home from school one day, I found my dad and his buddies dining on them. When our neighbor asked us where our rabbits were, my brother blurted out that my dad had eaten them. From the look on my dad’s face, I knew this was not to be spoken of. It wasn’t that our parents or relatives told us not to speak about these things, but more of an unspoken rule in an Asian culture. We always want to “save face,” so as it is, I am reluctant to share my story because I don’t want to be condemned.

By the way, my name is Chino. It’s not my real name, but a name given to me and a few hundred like me in the Texas prison system. Yes, I was named after a pair of pants. I was told that in Spanish, the word Chino meant Chinese, which I am not. I am a Vietnamese native, raised up in the dirty south—Houston—for most of my life. For the last 21 years, I’ve been buried or incarcerated by the State of Texas. You will not know who I am unless you are immediate family of mine or one of my few friends.

My culture will not allow me to speak upon the shame I caused. Even my nieces and nephews were told at one point that I’m in the Army. I learned of this during one prison visitation, when my niece Tasia mentioned that this is not the Army. I asked her, what made her say that? She replied that she had overheard her grandpa talking. With a smile, I covered the hurt and sadness that I felt inside. I will tell you now that it’s my fault and mine alone that I am here. I blame no one but myself. As a young man, my bad judgment and decisions crushed two dreams. With this one decision I made one night, cost one person to get hurt and myself to prison for 60 years.

I entered the Texas state prison at the age of 24, crushed underneath the weight of guilt for what I done and the shame I brought upon my family. I struggled because I’m confined in a world that consists of the worst of inmates, from psychopaths and murderers to robbers and child molesters. I really couldn’t seem to find anyone who could understand me, since prison is full of predators waiting to prey upon any weakness I might have. So I trusted no one. You never know the full depth of someone.

At times I also struggled with the meaning of the 60 year sentence that was given to me. I really couldn’t see how a young man my age can do 30 calendar years, day for day, before being eligible for parole. I never could have imagined what life would be like after 30 years in prison, for the hard reality was, I hadn’t even lived that long yet. I have heard, “A man has two lives and the second one starts when he realizes that he only has one.” I had to give up one life for me to survive in another. I owed my family, much because if not for the love of a father, mother, brother, sisters, and a beautiful niece, I wouldn’t be here today. It would have been much easier to give up on this life of mine.

The wish for death was strong in me at the time of my conviction. Once, I placed a collect call home. I can’t remember why. To my surprise, it was accepted by my two-year-old niece, Tasia. With this one conversation, everything was put in perspective for me. I asked her how she knew it was me to accept the phone call, and she replied that she just knew. But the moment she asked when I was coming home, right then and there, I broke down and cried. To this very day, I can still hear her words of comfort, the words of the sweet small child of my sister. “Bác Vu, don’t cry, it’s okay.” Over and over.

There is a long standing saying that prison is what you make of it, and this is true to an extent. But for Asians, it’s much more difficult since we are few. Racism is everywhere but it is at its worst in prison. I am separated because of my yellow skin color, my straight black hair and my slanted eyes. I don’t belong among others. With no one to show me the way, I was bombarded with rules, regulations, and standards. As I stood alone and watched from a distance, I learned the things I needed to survive. Luckily for us Asians, we are stereotyped, and because of this I have survived through the years. I know nothing of martial arts, but I know how to kick. It’s a good thing most inmates have seen “Saturday Morning Kung Fu Theater” growing up in the 80s. And because of this most left me alone.

My people were once called the “Boat People.” We escaped Vietnam after the war on boats. I know the hardship and risk my parents took in hopes of giving their children the American Dream. Because of my selfishness and immaturity, I have cost my parents their dreams for me. I am no longer privileged to stay in this country. I now have a detainer for deportation, which also exempts me from certain privileges and educational programs in prison. But I am not exempt from providing my unpaid labor to the state.

When entering the United States in 1980, my family and I were given green cards. But because of my conviction, aggravated assault with a deadly weapon, it was revoked. I am terrified to think that my family escaped Vietnam only for me to return there almost 50 years later, in handcuffs. I just hope that the land of my father feels that I am redeemable. To be honest, anywhere is better than to live without hope and the feel of sunshine on my face.

I know I am here to pay a debt to society. I know I am an immigrant privileged to be here, and I also do know that I’ve made a mistake. I am only human. I will have to live with this mistake for the rest of my life.