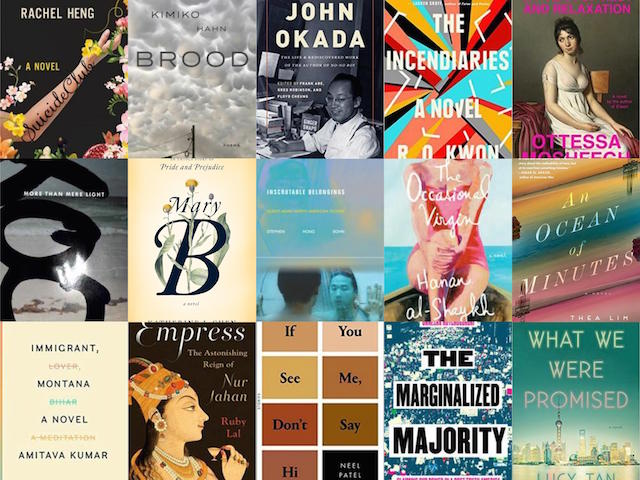

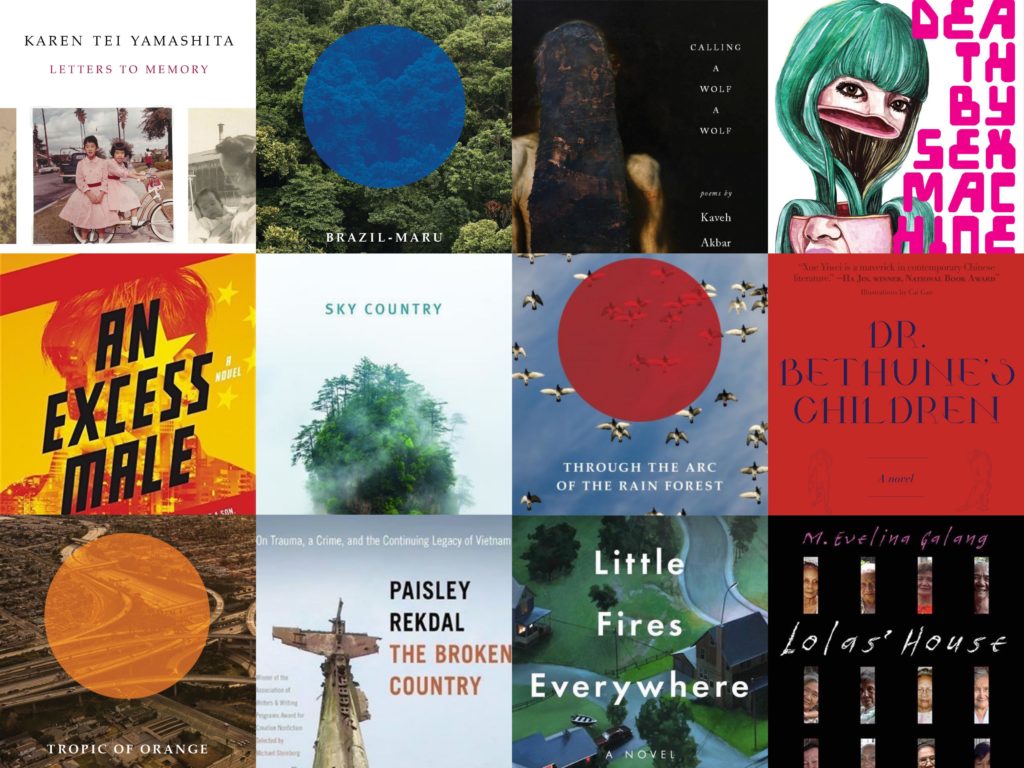

52 years since it was first published, the groundbreaking novel No-No Boy has been reissued by Penguin Classics. The new edition features an introduction by Karen Tei Yamashita.

May 21, 2019

Editor’s Note: On May 22, we learned that Penguin Classics, which republished No-No Boy this year, is not paying royalties to the family of John Okada. The University of Washington Press edition, first published in 1979 as a collaboration with the Combined Asian American Resources Project, has financially benefited the Okada family for 40 years. A conversation about No-No Boy and its legacy is forthcoming on The Margins.

*

“In the aftermath of World War II, Japanese Americans returned from American concentration camps to resume life in West Coast cities like Seattle, and John Okada wrote the novel No-No Boy to understand what happened and why,” writes Karen Tei Yamashita in her introduction to the newly reissued edition of Okada’s classic novel, published by Penguin Classics today.

In the following excerpt from No-No Boy, 25-year-old Ichiro Yamada has returned to his Seattle home in 1946 after two years in a Japanese American incarceration camp and two subsequent years in prison after having refused to be drafted into the US army during World War II.

From No-No Boy by John Okada, published by Penguin Classics, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

*

The Kumasakas had run a dry- cleaning shop before the war. Business was good and people spoke of their having money, but they lived in cramped quarters above the shop because, like most of the other Japanese, they planned some day to return to Japan and still felt like transients even after thirty or forty years in America and the quarters above the shop seemed adequate and sensible since the arrangement was merely temporary. That, he thought to himself, was the reason why the Japanese were still Japanese. They rushed to America with the single purpose of making a fortune which would enable them to return to their own country and live adequately. It did not matter when they discovered that fortunes were not for the mere seeking or that their sojourns were spanning decades instead of years and it did not matter that growing families and growing bills and misfortunes and illness and low wages and just plain hard luck were constant obstacles to the realization of their dreams. They continued to maintain their dreams by refusing to learn how to speak or write the language of America and by living only among their own kind and by zealously avoiding long- term commitments such as the purchase of a house. But now, the Kumasakas, it seemed, had bought this house, and he was impressed. It could only mean that the Kumasakas had exchanged hope for reality and, late as it was, were finally sinking roots into the land from which they had previously sought not nourishment but only gold.

Mrs. Kumasaka came to the door, a short, heavy woman who stood solidly on feet planted wide apart, like a man. She greeted them warmly but with a sadness that she would carry to the grave. When Ichiro had last seen her, her hair had been pitch black. Now it was completely white.

In the living room Mr. Kumasaka, a small man with a pleasant smile, was sunk deep in an upholstered chair, reading a Japanese newspaper. It was a comfortable room with rugs and soft furniture and lamps and end tables and pictures on recently papered walls.

“Ah, Ichiro, it is nice to see you looking well.” Mr. Kumasaka struggled out of the chair and extended a friendly hand. “Please, sit down.”

“You’ve got a nice place,” he said, meaning it.

“Thank you,” the little man said. “Mama and I, we finally decided that America is not so bad. We like it here.”

Ichiro sat down on the sofa next to his mother and felt strange in this home which he envied because it was like millions of other homes in America and could never be his own.

Mrs. Kumasaka sat next to her husband on a large, round hassock and looked at Ichiro with lonely eyes, which made him uncomfortable.

“Ichiro came home this morning.” It was his mother, and the sound of her voice, deliberately loud and almost arrogant, puzzled him. “He has suffered, but I make no apologies for him or for myself. If he had given his life for Japan, I could not be prouder.”

“Ma,” he said, wanting to object but not knowing why except that her comments seemed out of place.

Ignoring him, she continued, not looking at the man but at his wife, who now sat with head bowed, her eyes emptily regarding the floral pattern of the carpet. “A mother’s lot is not an easy one. To sleep with a man and bear a son is nothing. To raise the child into a man one can be proud of is not play. Some of us succeed. Some, of course, must fail. It is too bad, but that is the way of life.”

“Yes, yes, Yamada- san,” said the man impatiently. Then, smiling, he turned to Ichiro: “I suppose you’ll be going back to the university?”

“I’ll have to think about it,” he replied, wishing that his father was like this man who made him want to pour out the turbulence in his soul.

“He will go when the new term begins. I have impressed upon him the importance of a good education. With a college education, one can go far in Japan.” His mother smiled knowingly.

“Ah,” said the man as if he had not heard her speak, “Bobbie wanted to go to the university and study medicine. He would have made a fine doctor. Always studying and reading, is that not so, Ichiro?”

He nodded, remembering the quiet son of the Kumasakas, who never played football with the rest of the kids on the street or appeared at dances, but could talk for hours on end about chemistry and zoology and physics and other courses which he hungered after in high school.

“Sure, Bob always was pretty studious.” He knew, somehow, that it was not the right thing to say, but he added: “Where is Bob?”

His mother did not move. Mrs. Kumasaka uttered a despairing cry and bit her trembling lips.

The little man, his face a drawn mask of pity and sorrow, stammered: “Ichiro, you— no one has told you?”

“No. What? No one’s told me anything.”

“Your mother did not write you?”

“No. Write about what?” He knew what the answer was. It was in the whiteness of the hair of the sad woman who was the mother of the boy named Bob and it was in the engaging pleasantness of the father which was not really pleasantness but a deep understanding which had emerged from resignation to a loss which only a parent knows and suffers. And then he saw the picture on the mantel, a snapshot, enlarged many times over, of a grinning youth in uniform who had not thought to remember his parents with a formal portrait because he was not going to die and there would be worlds of time for pictures and books and other obligations of the living later on.

Mr. Kumasaka startled him by shouting toward the rear of the house: “Jun! Please come.”

There was the sound of a door opening and presently there appeared a youth in khaki shirt and wool trousers, who was a stranger to Ichiro.

“I hope I haven’t disturbed anything, Jun,” said Mr. Kumasaka.

“No, it’s all right. Just writing a letter.”

“This is Mrs. Yamada and her son Ichiro. They are old family friends.”

Jun nodded to his mother and reached over to shake Ichiro’s hand.

The little man waited until Jun had seated himself on the end of the sofa. “Jun is from Los Angeles. He’s on his way home from the army and was good enough to stop by and visit us for a few days. He and Bobbie were together. Buddies— is that what you say?”

“That’s right,” said Jun.

“Now, Jun.”

“Yes?”

The little man looked at Ichiro and then at his mother, who stared stonily at no one in particular.

“Jun, as a favor to me, although I know it is not easy for you to speak of it, I want you to tell us about Bobbie.”

Jun stood up quickly. “Gosh, I don’t know.” He looked with tender concern at Mrs. Kumasaka.

“It is all right, Jun. Please, just this once more.”

“Well, okay.” He sat down again, rubbing his hands thoughtfully over his knees. “The way it happened, Bobbie and I, we had just gotten back to the rest area. Everybody was feeling good because there was a lot of talk about the Germans’ surrendering. All the fellows were cleaning their equipment. We’d been up in the lines for a long time and everything was pretty well messed up. When you’re up there getting shot at, you don’t worry much about how crummy your things get, but the minute you pull back, they got to have inspection. So, we were cleaning things up. Most of us were cleaning our rifles because that’s something you learn to want to do no matter how anything else looks. Bobbie was sitting beside me and he was talking about how he was going to medical school and become a doctor—”

A sob wrenched itself free from the breast of the mother whose son was once again dying, and the snow- white head bobbed wretchedly.

“Go on, Jun,” said the father.

Jun looked away from the mother and at the picture on the mantel. “Bobbie was like that. Me and the other guys, all we talked about was drinking and girls and stuff like that because it’s important to talk about those things when you make it back from the front on your own power, but Bobbie, all he thought about was going to school. I was nodding my head and saying yeah, yeah, and then there was this noise, kind of a pinging noise right close by. It scared me for a minute and I started to cuss and said, ‘Gee, that was damn close,’ and looked around at Bobbie. He was slumped over with his head between his knees. I reached out to hit him, thinking he was fooling around. Then, when I tapped him on the arm, he fell over and I saw the dark spot on the side of his head where the bullet had gone through. That was all. Ping, and he’s dead. It doesn’t figure, but it happened just the way I’ve said.”

The mother was crying now, without shame and alone in her grief that knew no end. And in her bottomless grief that made no distinction as to what was wrong and what was right and who was Japanese and who was not, there was no awareness of the other mother with a living son who had come to say to her you are with shame and grief because you were not Japanese and thereby killed your son but mine is big and strong and full of life because I did not weaken and would not let my son destroy himself uselessly and treacherously.

Ichiro’s mother rose and, without a word, for no words would ever pass between them again, went out of the house which was a part of America.

Mr. Kumasaka placed a hand on the rounded back of his wife, who was forever beyond consoling, and spoke gently to Ichiro: “You don’t have to say anything. You are truly sorry and I am sorry for you.”

“I didn’t know,” he said pleadingly.

“I want you to feel free to come and visit us whenever you wish. We can talk even if your mother’s convictions are different.”

“She’s crazy. Mean and crazy. Goddamned Jap!” He felt the tears hot and stinging.

“Try to understand her.”

Impulsively, he took the little man’s hand in his own and held it briefly. Then he hurried out of the house which could never be his own.

His mother was not waiting for him. He saw her tiny figure strutting into the shadows away from the illumination of the street lights and did not attempt to catch her.

As he walked up one hill and down another, not caring where and only knowing that he did not want to go home, he was thinking about the Kumasakas and his mother and kids like Bob who died brave deaths fighting for something which was bigger than Japan or America or the selfish bond that strapped a son to his mother. Bob, and a lot of others with no more to lose or gain then he, had not found it necessary to think about whether or not to go in the army. When the time came, they knew what was right for them and they went.

What had happened to him and the others who faced the judge and said: You can’t make me go in the army because I’m not an American or you wouldn’t have plucked me and mine from a life that was good and real and meaningful and fenced me in the desert like they do the Jews in Germany and it is a puzzle why you haven’t started to liquidate us though you might as well since everything else has been destroyed.

And some said: You, Mr. Judge, who supposedly represent justice, was it a just thing to ruin a hundred thousand lives and homes and farms and businesses and dreams and hopes because the hundred thousand were a hundred thousand Japanese and you couldn’t have loyal Japanese when Japan is the country you’re fighting and, if so, how about the Germans and Italians that must be just as questionable as the Japanese or we wouldn’t be fighting Germany and Italy? Round them up. Take away their homes and cars and beer and spaghetti and throw them in a camp and what do you think they’ll say when you try to draft them into your army of the country that is for life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness? If you think we’re the same kind of rotten Japanese that dropped the bombs on Pearl Harbor, and it’s plain that you do or I wouldn’t be here having to explain to you why it is that I won’t go and protect sons‑of‑bitches like you, I say you’re right and banzai three times and we’ll sit the war out in a nice cell, thank you.

And then another one got up and faced the judge and said meekly: I can’t go because my brother is in the Japanese army and if I go in your army and have to shoot at them because they’re shooting at me, how do I know that maybe I won’t kill my own brother? I’m a good American and I like it here but you can see that it wouldn’t do for me to be shooting at my own brother; even if he went back to Japan when I was two years old and couldn’t know him if I saw him, it’s the feeling that counts, and what can a fellow do? Besides, my mom and dad said I shouldn’t and they ought to know.

And after the fellow with the brother in the army of the wrong country sat down, a tall, skinny one sneered at the judge and said: I’m not going in the army because wool clothes give me one helluva bad time and them O.D. things you make the guys wear will drive me nuts and I’d end up shooting bastards like you which would be too good but then you’d only have to shoot me and I like living even if it’s in striped trousers as long as they aren’t wool. The judge, who looked Italian and had a German name, repeated the question as if the tall, skinny one hadn’t said anything yet, and the tall, skinny one tried again only, this time, he was serious. He said: I got it all figured out. Economics, that’s what. I hear this guy with the stars, the general of your army that cleaned the Japs off the coast, got a million bucks for the job. All this bull about us being security risks and saboteurs and Shinto freaks, that’s for the birds and the dumbheads. The only way it figures is the money angle. How much did they give you, judge, or aren’t your fingers long enough? Cut me in. Give me a cut and I’ll go fight your war single-handed.