Is the lack of agency in the movie’s characters a reflection of centuries of colonialism? A Fil Am writer explores.

July 24, 2018

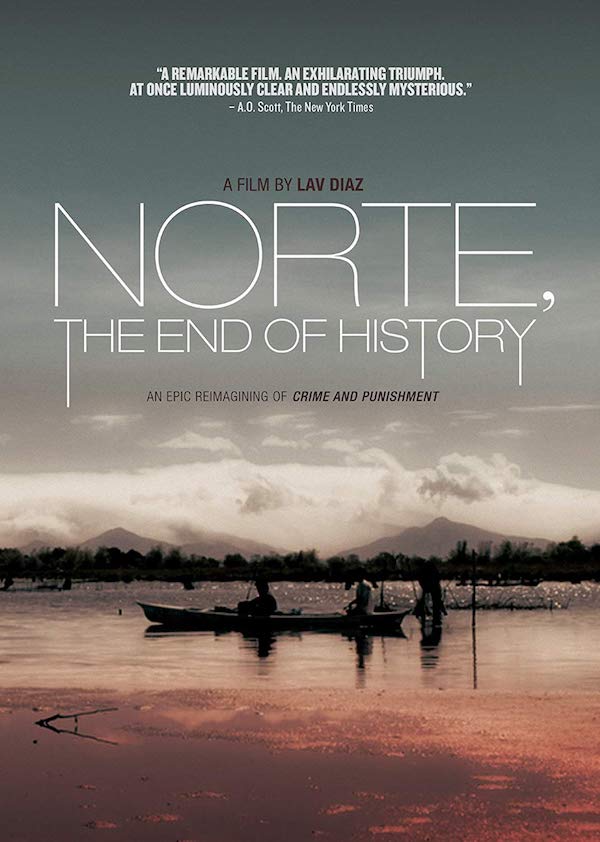

A woman walks to the edge of a precipice in a scene midway through Philippine independent filmmaker Lav Diaz’s four-hour film, Norte, The End of History. Originally released in 2013, Norte was screened for a cinema fest entitled “A New Golden Age: Contemporary Philippine Cinema” at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City where I watched it last summer with three other Filipina-American friends.

Will she jump off the cliff? The camera’s perspective of her from below suggests so. Earlier in the movie, relying on the advice of a callous lawyer, her husband confesses to a crime he didn’t commit and is sent to prison. Her family torn apart, the despondent woman instructs her sister-in-law to carry out a plan (undisclosed to us viewers) before we follow her to the edge. It appears she considers death her only escape from cruel injustice and a bleak future. Are her children doomed to orphanhood?

“People who have had everything thrown at them, with the goal of destroying them, still manage to find some kind of joy. That in itself is a miraculous victory; it is a triumph.”

Cut to the next scene: blinking lights like a circular beacon, a Ferris wheel at night and carnival music piping through the air as the woman and her sister-in-law watch her two children riding the carousel—this was the plan, thankfully: an evening of fun. Their eyes grin with joy and affection, a contrast to an earlier scene in the movie of a heartbreaking, tear-filled reunion with their father at the prison.

Laughter is a powerful antidote for lives in despair. In her recent interview in Aster(ix) Journal, the Haitian writer Edwidge Danticat observes, “I think joy is a kind of self-preservation against brutality and violence, and destruction in general. People who have had everything thrown at them, with the goal of destroying them, still manage to find some kind of joy. That in itself is a miraculous victory; it is a triumph.”

In a country of over 7,000 islands with a population of 103 million and another 10 million Overseas Filipinos or people of Filipino origin living in other countries as permanent residents, citizens, or as temporary workers, what exactly does being Filipino mean? I’d hoped to get a glimpse of the forces that shaped the identity of a country and its people, my people, through this celebrated filmmaker’s work. I consider it my ongoing education in the Filipino diaspora: to see my ancestral home and to understand a diverse culture more deeply through Filipino art, literature, and film.

Inspired by Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, the film merges a true story from a news article about a Filipino prisoner with the tale of a young dictator in the making, an allusion to Ferdinand Marcos before he becomes the Philippines’ president from 1965-1986 of which he reigned as dictator under martial law from 1972-1981. (The title, Norte, refers to Marcos’s birth region in the north of Luzon.) For those of us accustomed to change in American national leadership every few years—eight at most—the thought of 21 years under one commander and chief is inconceivable.

Norte strings together three people’s lives: a promising law student with lofty, if not questionable, ideological beliefs from a wealthy dysfunctional family and a poor man and his wife with two young children and a dream of one day owning a business. After the law student murders a moneylender, the family man is wrongly accused and sent to prison, leaving his wife and children to fend for themselves.

“It is this history that binds Filipinos, even those not born in the country, and it is the complexities of a colonial past that continue to astound me.”

The landscape serves as a compelling character too, and the camera lingers on characters’ often sad faces or evocative landscape scenes—field, river, village, road, seashore—for real-time effect, that is, much longer than one might be used to in mainstream Hollywood films. This is one of Diaz’s signature qualities, cutting away minutes, not seconds after, to the next scene. This creates a slower pace of storytelling, which offers a necessary grace to counter brutal acts or histories.

While immersed in themes of family, love, and political ideology, the film is equally about violence and trauma, class and privilege, transcendence and time, waiting and hope—this last one I really had to squint at the screen to see and even then, I’m not sure if it was just something I made up because who wants to leave the theater in despair?

It seems others had trouble with this theme too.

During the talk back with the filmmaker following the screening, a white man in an audience full of Filipinos observed that none of the characters had gone to the police or taken more charge of their various problems. He asked, “Why did they lack agency?”

This is a valid question, but especially in this context of a NYC art institution built from Western privilege, it bothered me. For Westerners like this white man and me, “agency” means action and choice. It means taking matters into your own hands. If the system isn’t working for you, you can challenge if not change it. That even if an authority is corrupt, you, particularly you as a white man historically, have had the means or the know-how to deal with it. “Agency” is your middle name.

Though I didn’t know how to answer this question right away myself, I intuited that larger forces in the Philippines (on screen and in reality), such as poverty and corruption, were at play, crippling agency. These forces are what this man couldn’t see. I have been similarly myopic from a limited American perspective.

All eyes on Lav Diaz, he responded that it was because of trauma, which was pervasive in the lives of the characters: trauma from over three hundred years of colonization by the Spaniards and then from one hundred years of American imperialism.

So there, I thought, thanking Diaz in my head for naming the shadows. It was historical trauma that I couldn’t identify. This historical trauma disempowered a colonized people, rendering them helpless in and dependent on a corrupt governing system from generation to generation, though it took me some time after the movie and some reading about this trauma to fully acknowledge it.

In those moments before Diaz’s revelation, however, I also understood the man’s question in another way. I translated what this man termed a “lack [of] agency” as a kind of compliance, like the way the wife in the movie listened to her lawyer even as he gave her bad advice to have her husband plead guilty for a (less, but still) harsh prison sentence or how a people can elect to live under a corrupt and brutal leadership.

I’ve wondered the same thing myself about the gentle, deferring, and easy going dispositions of scores of my Filipina/o relatives, friends, and acquaintances (though I’ve also known many quite the opposite too—fiery, temperamental, stubborn like my own father), who seem to follow authority trustingly. I questioned how much of it is part of the culture, a national character, and/or part of the personality of caring. Maybe none. Maybe all. Maybe some of each of these things.

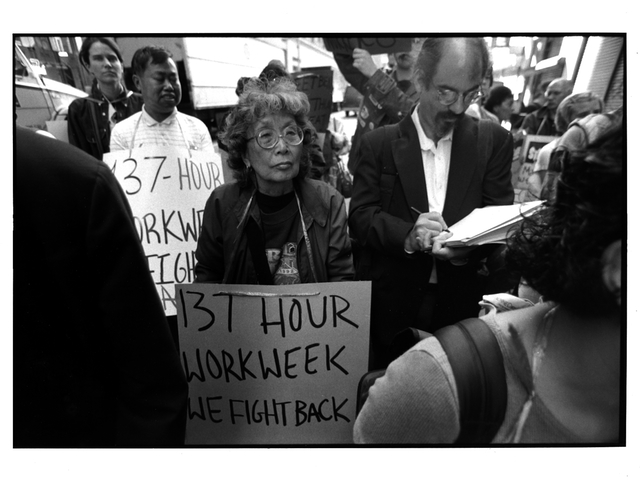

For certain, I have witnessed the ideals of a caring culture in action, striding alongside Filipino and Filipino-American friends and acquaintances on the streets of NYC in support of human rights and justice for Black Lives Matter, the Women’s March, and more recently in the Philippine Independence Day Parade, which involved a “die-in” on Fifth Avenue to protest President Duterte’s “drug war” that has claimed over 12,000 lives.

I grew up as an American, and I have been reminded by my parents and others fresh from the Philippines of this perceived “white” part of myself—my values of independence and privacy; my American education; not a small amount of my aesthetic and style, which came of age in American pop culture of the 1970s and 80s; my taste in music, which consists largely of musicians and singers of color, but also includes white country singers and hair bands; and how I speak—West Coast American English with a New York inflection. “You are American,” they’d say meaning I am a “white” American in brown skin.

“Being the colonized means you become a chameleon—first to blend in with your new surroundings to survive, live, thrive and then, if you have the presence of (a rebellious) mind, you figure out what you’re becoming a part of.”

Because of my growing knowledge of the history of the Philippines and the insidious effects of colonization and imperialism, this American side has been feeling increased friction with the part of me that is Filipina, the part I see in the mirror every morning and night, the part that recalls my experiences as a child of working class immigrant parents, who spoke to me in two languages in the house, Ilocano and English, and then spoke Ilocano, Tagalog, or English with their friends in the Filipino community and English with everyone else in our Southeast Alaska town.

There was always a layering and mixing of languages around me, which seemed natural. In multi-lingual NYC, where I have lived for the past 25 years, I hear Greek, Spanish, Chinese, Bengali, Portuguese, and Arabic spoken in my neighborhood on a daily basis. This is home, an expanding reflection of the world of immigrants I knew as a child.

What people like this man in the audience don’t know or may not see, at least the ones who don’t consider colonization as a cause of trauma or who aren’t exposed on a deeper level to a once-colonized or present-day colonized people (read: much of the world), is that being the colonized means you become a chameleon—first to blend in with your new surroundings to survive, live, thrive and then, if you have the presence of (a rebellious) mind, you figure out what you’re becoming a part of. The changes are displayed in the external world, but at home, these chameleons continue to embrace their culture, resisting full transformation behind closed doors.

My parents, like the 10 million Filipinos living outside of the Philippines today, are chameleons and I imagine them inheriting this survival trait from their ancestors who had become chameleons in their colonized country for hundreds of years. They adapted. (The answer seems obvious when under the sword or gun or promised economic and/or political gain or independence.) They learned to speak the language of the colonizer as they continued to speak their native tongue at home. They lived with the colonizers under their governing system—the colonial government of Spain, followed by a push and pull of American power and conquest—and many worshipped their Catholic god. I am a product of this history, both an enemy and friend to myself.

Diaz explains the problematic term “Filipino” in a 2016 interview in Guernica. He observes, “‘Filipino’ is the Spanish side of our history. The islands were named after King Felipe, so we became known as Filipinos. It’s a brand, it’s a name. But we’re Malays. Before colonizers came to our shores, we were Malays. My praxis is about being Malay—the struggle of the Malays before we became Filipinos.”

What is revealed in his observation—and speaks to my questioning of a coherent “Filipino” identity—is that this identity belies an ancestry defined by a complex history of migration and colonization of the over 120 languages and dialects in this Southeast Asian archipelago stretching over 1,149 miles, roughly the distance between Seattle to Los Angeles. Centuries before explorer Ferdinand Magellan’s arrival in 1521, launching the Spanish colonial period, Arab, Indian, and Chinese traders reached the country’s shores. Settlers and invaders sailed on the South China Sea to the West and the Philippine Sea to the East, to what we call today the Philippines.

In truth, Filipino identity and before this, Malay identity, were built on a multiplicity. It was and will remain a hybrid. It endured colonization and—as colonized, hybridized peoples do—regenerated what was lost to become something whole again, like a newt that grows a new tail when the old one is lopped off. In the diaspora, as this identity adapts to a larger culture, certain aspects of Filipino culture survive and thrive. When I meet someone who also claims Filipino ancestry, our conversations often lead us to identify our cultural connections.

We may have different family dialects or religious backgrounds, but share an intimate knowledge of Filipino foods or a penchant for puns or profane humor. In our recognition is an unspoken understanding of our beleaguered ancestral country and people. It is this history that binds Filipinos, even those not born in the country, and it is the complexities of a colonial past that continue to astound me.

Take, for example, skin color. It was satisfying to see brown faces on the screen instead of the prevalent mestizo actors, that is, the light-skinned American and European Filipinos playing the leads, as they commonly do in Philippine cinema. Lighter (whiter) skin is more valued. It is another maddening and problematic legacy of colonialism. Part of me wishes I could just somehow resolve this convoluted legacy and move on, and I do. Sometimes. Internalization is gnarly. Another part of me continues to resist.

So I return to the question: Why is it that the characters in Diaz’s film lack agency? Because what choices did these film characters have? For sure, they are a reflection of the limited choices of people in the Philippines. They lived in either a dysfunctional and broken privilege or in a close-knit, loving, but seemingly powerless, poor working class.

“There is a fierce loyalty in the love and care displayed on the screen and what I witness in Filipino culture; what they all seem to be saying is: when everything goes to shit, keep caring for and loving those around you.”

In response to trauma, the historical trauma identified by Diaz and the traumas depicted in the movie, the characters restored a routine in their lives like the wife did in selling her vegetables from her cart or they adapted to the confinements of their new reality like the husband did in tending a prison garden and returning to his family through his dreams at night. Or they committed even more unthinkable, violent acts like the law student who, after stabbing the moneylender, raped his own sister and then killed his one closest family member, his childhood pet dog. Perhaps this is what living in post-colonial trauma means, as revealed in Diaz’s film: it’s complex.

But look closer at the innocent ones: the jailed husband and the stranded wife loved and cared for those around them despite their hardships. Their virtuous concern for others offers redemption in trauma’s darkness. The husband nurses a wounded fellow prisoner who’d tried to kill him. The wife brings joy back into her children’s lives in the whirl of carnival rides. Though not lit up by typical Filipino humor and puns, there is a fierce loyalty in the love and care displayed on the screen and what I witness in Filipino culture; what they all seem to be saying is: when everything goes to shit, keep caring for and loving those around you.

Perhaps the pain remains, but more spaces open up. Spaces for a kind of liberation. Adapt and love. It’s a way through trauma. Indeed, it’s a way through life. However, Diaz is not hinting at solutions in these moments; they are merely my own projections of hope and admiration for what I consider skills of a chameleon people. On the contrary, the audience is left disheartened by the end of the film over what is to become of the children and the country.

What’s left? Something that filmmaker Diaz shared that evening at the MOMA comes to mind and hints at a more subversive form of responding to life’s challenges. He recounted how the eldest daughter of the late dictator, Imee Marcos, a politician herself, supported the movie while they were filming in the northern region. Diaz confessed to the audience how he had sent away Governor Marcos’s helpful “guides” to lunch while they filmed more obvious scenes insinuating the dictator’s early life. Such a clever move on the filmmaker’s part. As a result, he has become “persona non grata” in that region of a country often ranked high in the index of most dangerous places in the world to be a journalist. People are silenced (read: killed) for exposing truth in the Philippines.

The lesson here? When making art that mirrors life means coming face to face with a veritable obstacle, this is what one must do: work around the obstacle. Diaz’s maneuver was resourceful and full of moxie. It was life mirroring art. Ironic, hysterical, improvisational, courageous, it’s a skill to create poetry out of the moment. In other words, it was agency.