Mia Kang interviews filmmaker J.P Chan about his latest film, and casting Asian actors in lead roles

July 16, 2014

When at a friend’s behest I recently attended a screening of writer-director J.P. Chan’s first feature film, A Picture of You, I felt my usual mix of curiosity and trepidation about going to see a made-on-a-shoestring independent film, and even more dangerously, one that appeared to explore racial identity. But shortly into the picture, which follows estranged siblings Kyle and Jen as they pack up their deceased mother’s house in rural Pennsylvania, I was essentially fist-pumping with delight in my seat. After a series of melancholic and beautifully shot opening scenes, a quick plot twist turns the film into more Hangover movie than wistful indie: when Kyle and Jen discover the unexpected on their mother’s computer, it sets off a series of misadventures that are sometimes slapstick, sometimes purely witty, and sometimes downright suspenseful. Throughout, the film’s blunt humanity deploys clever provocations about ethnicity, prejudice, and mistaken assumptions.

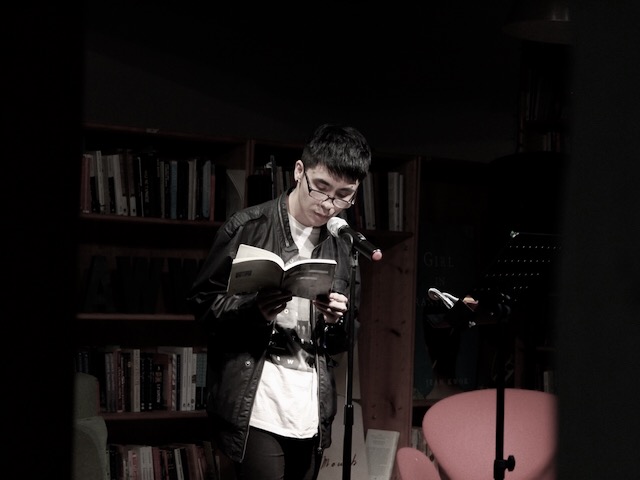

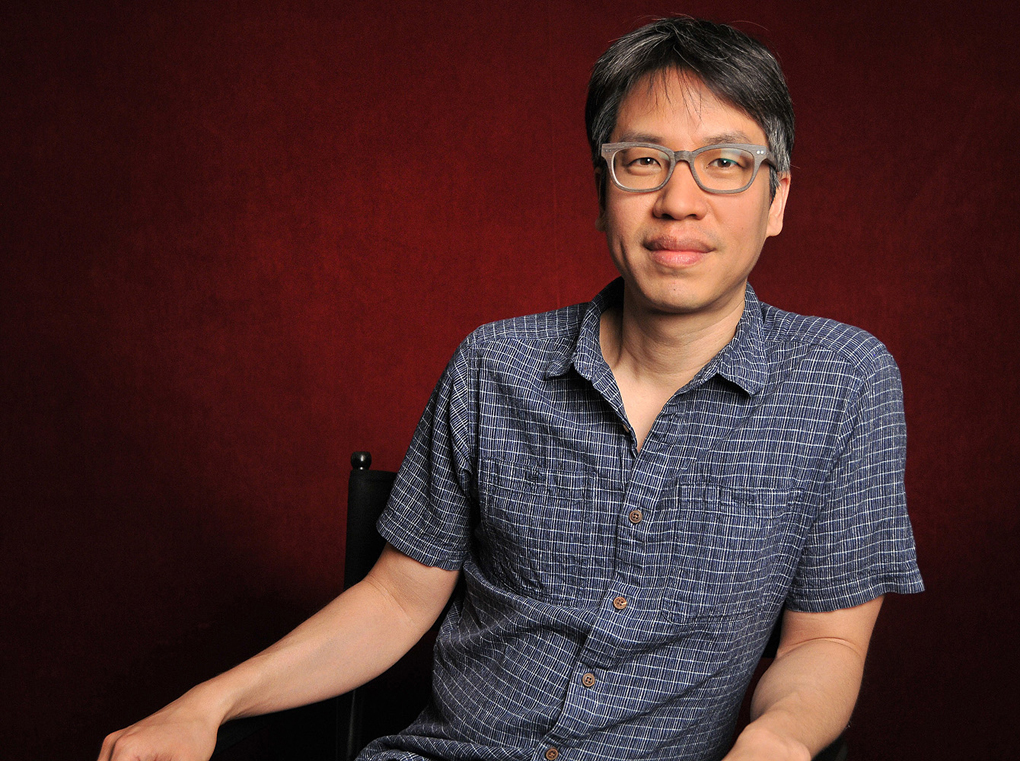

I interviewed J.P. at Ten Ren’s Tea in Chinatown. He is a neatly energetic person, giving the impression he could self-sustain indefinitely on ideas and drive alone. As we spoke, the fact that he holds a master’s degree in urban planning seemed oddly complementary to his approach as a filmmaker. With no formal training in film, he is acutely thoughtful and self-aware about his process, which at its core might be termed idealistic pragmatism. Prior to A Picture of You, J.P. wrote and directed six short films, and his work has screened at film festivals including Slamdance, Tribeca, and SXSW.

-Mia Kang

Mia Kang: This is your first feature film. What made you pick this script?

J.P. Chan: I had already written a couple feature scripts before, but all of them were on a bigger scale than what I could conceivably do as a first feature. I wanted a first feature that was compact and could be done with few resources, but also one that was ambitious in its scope and structure. None of the features I had previously written fit that bill. In the middle of 2011, I set about writing two new scripts. At the end of the year after seeing how they came out, I picked A Picture of You. The film was inspired by various events in my family, notably the passing of my mom several years earlier and how that changed the family dynamic.

Where did you grow up?

I grew up in a town called Nutley, NJ. It’s only about twelve miles west of Manhattan. When I was there, it was mostly working to middle class Italian American, Irish American. My family were some of the few people of color there, period. Most of the Asians I knew there were people like my father, who moved to Nutley to work at the pharmaceutical company there. Nutley was the U.S. headquarters of the Swiss pharmaceutical company called Roche. They make Valium and some other stuff.

Did you feel connected to an Asian community?

Not at all. I’m 44, so I grew up in the 1970s and ’80s. [Asians] were still very much in assimilation mode at that point. You just wanted to blend in. I didn’t have any Asian friends until I got to NYU; the only Asians I knew growing up were people who came to our household. My dad is the oldest of nine kids, and my mom is one of eight children. They were the first in their families to come to the United States, so everyone from their extended families flowed through our family as they immigrated. So no, I didn’t really feel connected to the Asian community. Quite the opposite; I felt like it was weird that my family was so different from everyone else’s. Everyone else’s family was American.

Did you always want to be a filmmaker?

I always wanted to do film, but I didn’t really know what a filmmaker did. I grew up watching ’70’s sci-fi movies and TV, like Star Trek and Star Wars. In fifth grade, I tried to shoot a film with a friend of mine. We had a super-8 projector, but we couldn’t get our hands on a super-8 camera. We gave that up after a couple months. It’s hard to sustain things in fifth grade when you don’t have support. It was always in my mind to do film, but because I grew up in a working-class household, there wasn’t any example—art was for somebody else. No one I knew did art for a living or anything artistic; we worked in restaurants. My dad was a chemist, so he had a white-collar job, but once my parents divorced, we were solidly working-class. My mom worked in a restaurant.

What’s your day job now?

I’m a multimedia director for the MTA. I’m basically the lead videographer there. I run our YouTube channel, which has lots of trains and buses videos. I shoot videos and I manage the videographers.

What about science fiction? You liked it as a kid, and there are a couple of sci-fi references in A Picture of You. Do you read science fiction also, or was your interest always film-based?

It was always more film- and TV-based. I did a little bit of a reading when I was a kid, but I haven’t really kept up. I did do a sci-fi movie a couple years ago. It was a short, part of the ITVS Future States series. I had a lot of fun doing it. I definitely want to revisit that genre again in the future.

Before this meeting, I sent you a message saying “I’m wearing what Google appears to confirm is mint green,” and you responded, “As long as it’s not Google Glass.” How do you really feel about Google Glass?

I think it’s inevitable. It’s in the vanguard. That kind of capability—instant access to information, instant analysis of your environmental factors—is going to be built into everything we do. It’s all coming soon. And with it, lots of really, really interesting privacy issues, which I find fascinating.

Your films Digital Antiquities and A Picture of You both explore digital records in relation to memory, perception, and identity. But I guess what you’re talking about is more connected to places. Are you talking about smart cities?

As an urban planner, yeah, the smart cities thing is interesting. What’s most interesting to me—and I’m working on a script about this—is the future of privacy, and whether privacy is in some ways an antiquated notion. When societies were far smaller and less urban, did people really have privacy? When you were living in a village, didn’t everyone know each other’s business? Privacy maybe evolved during the industrial age, when you could have the anonymity of an urban life. It’s interesting how technology could bring us back to the time when everyone knew everyone’s business, for better or worse.

A Picture of You moves among several genres. It starts out reflective, dramatic, and poignant and morphs into a hilarious series of adventures. Does genre-crossing come naturally in your creative process or do you think consciously about form as you construct a film?

I think a little bit of both. I’ve been told that a lot of my movies combine different genres. In A Picture of You, I deliberately wanted to tackle head-on the ideas and expectations of genre, especially for independent film and for a first time feature director. I wanted to thumb my nose at what those expectations were. There are cliches in the indie world just like there are in Hollywood. So yeah, it was deliberate, and it fit with the emotional journey of the characters. We all experience that one day: you feel like you’re living in a drama, and then you realize you’re acting in a comedy, a sitcom. We’ve all had those moments.

Did you feel there were specific expectations about you as an Asian American filmmaker? You’ve screened at a lot of Asian American film festivals.

I have. I don’t know what the expectations are. I mean, I’m such a small fish that I don’t know if anyone’s sitting around having expectations of me. I’m just a normal guy who just started making film at a later age than most indie filmmakers. The script didn’t go through any of the prestigious development programs that are prevalent in the indie world. I’m very cognizant of and humbled by how competitive the business is and how fundamentally hard it is to make good work. There’s no guarantee.

At the A Picture of You screening I attended, you said in the Q&A that you started making films nine years ago. Do you have a methodical approach for teaching yourself filmmaking without any formal training program?

It’s methodical in that I tried to just keep making movies. I tried to shoot at least one short a year, then take that short on a festival circuit, so I could learn more about how to make a movie and about the business of film. That’s how I learned, and I met many collaborators during the festivals who would later work with me on the feature film.

Were there particular influences either in film or writing for you?

Creative influences or business influences?

Either one.

I admire directors and writer-directors who can continually keep making movies, especially ones who work in different genres. An early influence was Woody Allen—growing up, seeing his movies, and just being enchanted by the humor and intelligence of them. That was a big reason why I wanted to come to NYU and live in New York City. I was a working class Asian kid in New Jersey. I couldn’t articulate it at the time, but I really wanted to be a Jewish upper class intellectual. Who could, you know, always be nebbishy but still date really good looking women. That’s obviously a problematic thing in Woody’s stories in some way, but it was kind of like nerd heaven. It looked like it would be nerd nirvana.

There’s a lot of humor in A Picture of You and in your shorts as well. Aside from Woody Allen, where does your sense of humor come from?

I think it was maybe from being in a household with my mother. She had a really hard life, raising us as a single mom—high school education, immigrant—but she always had a great sense of humor. There was always laughter in the house, despite the trying conditions. That’s just part of my DNA: “You can go through unbelievably horrible stuff, but as long as you can laugh with the people you love, you’re gonna be okay, you’re going to get through it.” I guess that was the subtext in all that.

Can you talk about the audience response to A Picture of You? Any particularly weird or interesting reactions?

At our premiere, there was a woman who watched the entire movie and then asked in the Q&A, “So was this entire film shot in Japan?” Which is so random, right?

Oh my God.

People in the audience were kind of snickering at it. I wasn’t offended or anything; I was just trying to answer the question honestly and trying to figure out what would make her think the film was shot in Japan. There’s no reference to Japan; people speak in clearly American contemporary English, and there are New York state license plates on the cars. Basically, there’s no indication that it was shot anywhere other than the United States.

*laughs* Right.

But on more reflection, it’s clear why she thought that. It’s because the lead characters were Asian, and while it’s mostly a family story, in 2014, we’re still not used to seeing [Asians in leading roles]. That woman figured she had to make a connection—there must be some reason why there are Asians; it must be connected to the story somehow. It’s so interesting that ingrained narratives about what things are supposed to be will overpower even plain evidence to the contrary. But that’s the whole basis of stereotyping, right? So that’s been eye opening, but I didn’t set out to change the world with my movie. It’s nice that this film might change minds a little bit here and there.

Yeah, the film is very tuned into racism, but it addresses it in a subtle way. For instance, when Caucasian locals identify the siblings as their mother’s kids, and they respond, “Did you just racially profile me?”

They look like people you and me know, right? [The main characters] are a diverse group of friends in their 20s and 30s, and they talk the way we talk about race. They are very much people of this time, I think. They acknowledge their ethnicity, their race, but they’re not defined by it. And there’s also this city superiority—when they go out to the country, they assume all the white people are going to be bumpkins and less tolerant. They have their own prejudices, which I think is revealing.

In terms of your creative process, what form does the idea take? Is your inspiration visual, or is it language or writing based?

If I’m going to be really honest, it’s usually a combination of available or conceivably available resources and whatever questions I want to explore in my life. In that way, it’s very opportunist. I’ve had to be that way, and I hope to work in a different way someday. The danger [of that approach] is that I won’t be able to dream bigger. But I have a full time day job, and I have to stay at that day job to pay my rent. I can’t go away for six months to shoot something in the Arctic, you know? I try to think of a cool thing I can shoot that is manageable but doesn’t feel small and typically indie, like it all takes place in someone’s apartment. I write movies not to dictate or provide any answers; I write strictly to explore the questions brewing in my mind. I rarely reach any conclusions, but I think as long as the journey is honest, it will work as a movie.

How do you balance your job and your life as a filmmaker? Do you have a regular schedule? Do you write every day?

When I’m in writing mode, I have a writing buddy. He’s someone who like me has a day job—he’s an attorney, and he’s extremely disciplined. I get my discipline from hanging out with him and forcing myself into his schedule. He and I work on scripts “together” in that we go to the same Panera Bread in NJ every weekend and sit for hours, just writing, not talking to each other. So that’s my process. I find it very difficult to write in my house because there are too many distractions, mostly my cat and napping—

Food.

Yeah, and the refrigerator. So I usually have to get myself out. If Panera Bread or Argo Tea Cafe ever wanted equity participation in my movies, they could have it. I’ve written all my scripts there, in these two chain coffeehouses.

That’s funny.

It’s nice to be in places where other people are working on laptops, because writing can be so lonely, you know? When I’m at my house, writing can often get really depressing. To write something good, I feel like you always have to go to the darker places, even if it’s a comedy. I can do that in a cafe much better than I can do it at home, ‘cause otherwise, I’ll stop typing and start crying or something and then play with my cat.

Right. In your short film Beijing Haze, there’s a line, “I used to dream about America, now I dream about China.” For me, that relates to the nostalgia in A Picture of You and Digital Antiquities. Can you talk about that idea? There seems to be a repeated theme of things you can almost get, but not quite.

Oh, I’ve never thought about it that way before. Not consciously. In Beijing Haze, that line came about ‘cause we wanted to explore the boundaries between dreaming about what your future life and future self could be and your remembrances of your past. I wanted to juxtapose those ideas, mix them up, and make them like the soupy haze of the Beijing skyline. I wasn’t trying to make any comments about U.S.-China relations; it was really about your dreams and your aspirations and your memory.

What are your dreams for the future?

My first thought right now is to get A Picture of You out to an audience that will love it. It’s a small weird film, but people have really responded to it. For my own development as a filmmaker, I also want to understand how a film reaches audiences. We’re self-distributing partly out of necessity, but we also don’t think a distributor would be able to take the time and care that we can. I think the film industry at the independent level is going the way of indie music. It’s incredibly competitive, and it’s a bifurcated system where you have mega stars who dominate everything and then a whole bunch of people who are not making any money from the artwork anymore. And you have to devise sustainable ways of getting the work out there.

Yeah, that’s interesting. So, if as a kid you didn’t feel or even imagine art could be a career option for you, what made your attitude shift? When did you start thinking, “Oh, I really need to start doing filmmaking, because that’s what I want?”

It seems to me that these questions all connect. We’ve been talking about economics this whole conversation—it’s not a romantic way of looking at it, but it’s the only way I know… What made me do it? Ironically, what made me consider film as a career was having another career. I was working at MTA as a transportation planner and that was a secure path. I could see where that was going to lead. It made me realize that for the longest time, I’d had this passion inside of me to do films, and I should explore that. Just like I love cities and I love planning, I love film. I thought, I have a day job that pays the rent, so why don’t I explore this other thing? Maybe it’ll be a hobby, and maybe it’ll peter out after a film or two ‘cause I won’t like it, or maybe it’ll be really cool. I pursued it without thinking about what kind of job would come out of it, ‘cause I don’t think I can think that way. I can articulate long term goals, but really, it’s the day to day that matters. I’ve been living with this movie for three years now, day in and day out. The question is, are you willing to do what it takes to get this thing done and get it out there? I think of myself as being in my ninth year of film school.