How performance and storytelling helps to nurse old wounds and heal trauma.

May 26, 2021

Potri Ranka Manis knows that hospital patients turn apprehensive during the night. To soothe their anxiety, Potri would introduce herself as “Poetry,” a phonetic play on her name. Then comes the singing. As if she were still onstage, she launches into an a cappella rendition of “Everything’s Alright” from Jesus Christ Superstar on a patient’s bedside. Performance is Potri’s healing practice.

“As an indigenous person, we chant to our sick,” she says, referring to the traditions of her Maranao tribe in the Philippines.

When Potri performs the Indigenous traditions of the Philippines underneath the spotlight or in front of an audience, she transforms them into art. For Potri, this art is a form of healing and recovery. “My life is full of trauma, and at times you have to shut out all this trauma,” she laughs.

Potri, who now works at the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, has been on the frontlines of epidemics and a witness to a genocidal martial law dictatorship in the Philippines when she was held as a political prisoner as a teenager. The theater company she founded, Kinding Sindaw, aims to preserve and celebrate the Indigenous traditions of Mindanao in the Southern Philippines.

The COVID-19 pandemic is not the first major health crisis to challenge Potri’s training as a nurse who uses her skills as an Indigenous performer into her practice. Potri immigrated from Mindanao, a Muslim-majority island in the Philippines. She arrived in New York in the middle of the HIV/AIDS crisis more than 30 years ago, along with a generation of Filipino immigrants and healthcare professionals during a crucial nursing shortage in the country.

After a shift at Cabrini Medical Center in Gramercy Park, she would proceed to work as a school nurse. During the evening, she would rush out of her scrubs and change into costume before performing for a packed theater.

“Because I’m an artist, I don’t get burnout,” says Potri, who claims that an hour-long power nap during a night shift can be equivalent to eight hours of sleep. In the middle of a night shift, she would look for an empty room to line up three chairs together where she could lay down. All she really needs is one hour of sleep. The CDC-recommended hours of sleep for women her age are seven to nine hours, but Potri doesn’t care for the 24-hour day.

“She tries to make everyone be a nurse at some point,” says her daughter, Malaika Queaño who now works with Kinding Sindaw. The work is noble and worthy, but for Filipino immigrants, the job remains stable.

□ □ □ □ □

When I ask her how she approaches a patient in pain, she thinks for a moment. “I’ll just tell you a story,” she says one evening over Zoom from her apartment in Jackson Heights, Queens.

Potri recalls her five-year stint working in the AIDS unit and encountering a young patient under excruciating pain one night. The patient begged the nurses for additional morphine. “I was taking care of patients with unimaginable symptoms,” she says, “It felt like centuries.”

While she attempted to quell the patient and explain that more morphine would damage his lungs, she spotted a guitar under the patient’s bed, along with papers from a musicians’ union.

Instead, Potri handed the patient a pen and paper and said, “This is your morphine.”

“He said, ‘Are you crazy?’” Potri remembers with a smile, “I said yes!”

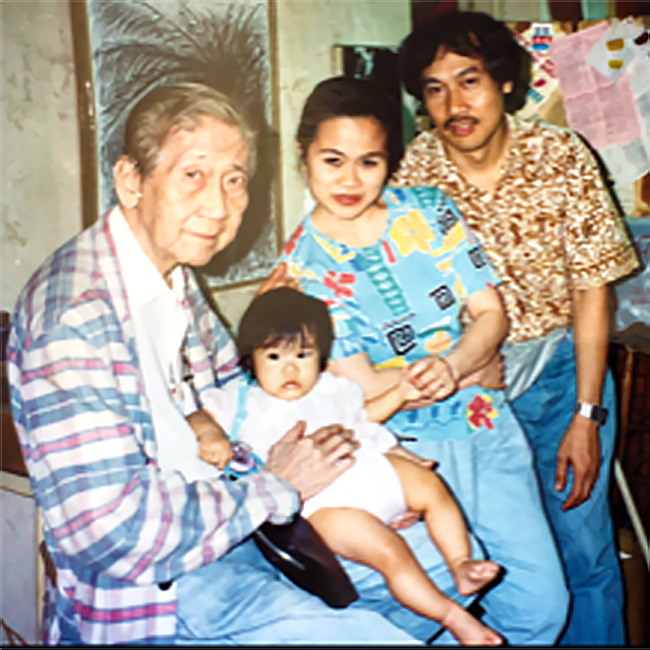

Potri: “The nurses thought my approaches were crazy.” Photo from kindingsindaw.org

While her daughter remains more reserved in her opinions, she has had a front row seat to her mother’s eccentricities from a young age. “She has a way of connecting with people and it doesn’t matter how old they are or where they’re from,” Malaika says, “We’ll take a cab and she’ll manage to know the driver’s life story.” Later, she adds, “Part of my role in Kinding Sindaw is to reel it in.”

Art has always been the vessel of her stories. “You’re making the other person feel good,” Potri explains. The epics of the Maranao, an Indigenous people of the Southern Philippines, are meant to be sung with pride. The stories of her ancestors should be recited with pleasure lest they be forgotten. “The nurses thought my approaches were crazy,” she says, remembering the unconventional practices of her time in the AIDS unit.

Growing up in Mindanao, Potri would accompany her aunt, an Indigenous midwife, to deliver babies. While Potri was just six years old, she learned how to wrap an infant in banana leaves. Years later, she would understand that the sterilized leaves clean the baby and relieve the mother’s back. Potri learned which herbs are medicinal and exposed herself to Indigenous practices of caring for people. “Before I became a nurse, I was a trained healer,” she says.

Potri’s aunt, who was conscious of succession and nurturing the culture, taught her the dances and traditions that she performs and teaches to new generations of audiences and students today. The process was part of her lamin, the traditional training for a young Maranao woman who is taught ancestral stories, chants, embroidery, and how to become a model for the people. This upbringing motivated and informed her nursing education, despite the pejorative misconceptions behind village healers and Indigenous practices which were seen as illegitimate by Western nursing standards. Potri still dreams of acquiring land in Mindanao and developing a garden for Indigenous healers.

When she was 13 years old, the military police held Potri as a political prisoner in Davao City where officers invaded the lands of the Moro people and tortured her for information. She was allowed to attend school accompanied by guards on the condition that she continue her studies and report to barracks every Friday. During the government military occupation in Mindanao of the 1970s, Potri attended nursing school, wrote poems, and performed plays as a form of demonstration. One play she wrote, “Red Dandelion,” is about a dandelion that criticized the school. She named the main character, a nurse, “Tina Tapakan,” a Tagalog pun that means “to be trampled on.”

□ □ □ □ □

When I speak with Potri over the phone during her lunch break, she is sitting in her apartment and reviewing patients’ charts. When she has your attention, however, she wastes no time. She leads me into a dramatic rehearsed narrative of her life where she has mastered the beats and punchlines. It is not her first time telling her life story, and she would tell it to you herself if she could. “I remember when the four-wheel drives came in and cut the trees,” she says of the military and corporate invasion of Moro villages and farms. She has profound pride in sharing childhood stories and the desire to preserve it.

Her deep encyclopedic knowledge of imperialistic history in the Philippines is reflected in her choreography and performances in Kinding Sindaw, but an oral history from the storyteller herself tells only half the story. The epic poems and mythology must be witnessed live and onstage. In Lemlunay, the main character is born into the T’boli tribe of Mindanao where he struggles to find a sense of belonging.

Diane Camino, the dance captain and teacher at Kinding Sindaw, grew up in the Bronx, and similar to Lemlunay’s protagonist, was eager to find a deeper understanding of her Filipino American culture. When she joined the dance troupe at 16 years old, the stories and dance traditions of an underrepresented people in the Philippines made direct connections with her self-esteem and self-worth as a teenager. She had found a space that she did not know she was looking for. Twenty-five years later, she says, “Now I can help others to face their own traumas growing up in America and finding identity.” Like Camino, people often turn to art to seek comfort and refuge in times of crisis.

Potri has often faced discrimination in the workplace and among Filipino colleagues, as someone who wears a hijab and comes from the historically Muslim and Indigenous Mindanao. This came to a point that she does not identify with the Filipino American community, She remembers being called “traitor” by a Filipino coworker in the aftermath of 9/11.

“Nursing is not easy. [I’m] dealing with diverse communities with their own cultures, most of the time, racists,” she says. “The pressure of work causes internalized repression.” When a head nurse once demanded that Potri remove her hijab, she noticed a nun in a habit serving as a chaplain in the hospital. She applied for chaplaincy and attended weekly training and hours of internship in order to assist in the spiritual journey of patients and wear her hijab again.

Potri: “Villa would criticize the young poets.” Photo courtesy of Potri Ranka Manis

□ □ □ □ □

Over the years, Potri has become a notable figure among Filipino creative circles in New York City. She has crossed paths with the likes of modernist poet José García Villa, known as the “Pope of Greenwich Village,” whom she met when she hosted poetry readings at her hospital housing in Gramercy Park. “Villa would criticize the young poets,” she says with her roaring laugh.

Photographer Corky Lee, who historicized the struggles and triumphs of Asian Americans, was instrumental in the formation of Kinding Sindaw; he documented its very first show. “When I arrived [in New York], I was doing solo dances, and he said [we] have to become an organization,” says Potri.

Lee provided the company’s initial funding.

Potri recalls receiving phone calls from Lee a few days before his death from Covid-19 in January 2021 asking where he should go for tests. “I told him to write his experience,” she said, so that she may hold the caregivers accountable.

After years of being the go-to health professional for her large network of artists, poets, and kabayan in New York, she reflects on what more she might have done to save the people who reached out to her. “I know I didn’t go wrong, but there’s always the question of where I went wrong,” she says.

Today, Kinding Sindaw educates and spreads awareness of the displacement and eviction of the Moro Muslims in Mindanao from military siege. Potri assumed the duty to nurture the traditions from her aunt, and her work continues in New York City, not without worry and hesitation.

“We cannot save, but we can be an assistance in staying away from commodifying culture,” she says. Potri’s art has helped to heal her from the trauma of a life wrestling with colonized cultures in the Philippines and the United States, and she feels a responsibility to share it. She is aware that during times of crisis, including state-sanctioned violence and a pandemic, people tend to turn to art for comfort.

The artist in her will continue to share her culture onstage and teach dance lessons every weekend, while the nurse and healer in her will continue to sing “Everything’s Alright” to her patients at night:

“Sleep and I shall soothe you,

Calm you, and anoint you,

Myrrh for your hot forehead,

Then you’ll feel

Everything’s alright,

Yes, everything’s fine…”