Philippine Dance Group Kinding Sindaw Is NYC’s Cultural Warfront Against Indigenous Erasure

May 7, 2020

The show begins with a scene of displacement: A group clad in elaborate textiles but crouching in tents made out of ropes and tarpaulin, unpacking shopping bags and carts that had been hastily stuffed with clothes and canned food, all acted out over a lilting drumbeat and tinkling gongs that swing just slightly out of time. Crashing cymbals and frantic shouts interrupt the solemn scene. The people flee.

It’s a snapshot of present-day Marawi, a once booming metropolis on the island of Mindanao and one of the Philippines’ largest majority-Muslim cities. It was razed to the ground by government forces in 2017 in a military siege allegedly meant to purge the city of ISIS militants. One hundred thousand people—about half the city’s inhabitants—were displaced by the conflict, and they remain so to this day.

Pananadem is the latest production by Kinding Sindaw, a NYC-based theater company that aims to preserve and proliferate the ancestral art forms of the Indigenous people of Mindanao in Southern Philippines. “Kinding Sindaw” means “movement of light,” and “pananadem” means “remembering” in the language of the Indigenous Maranao people. The Maranaos are one of the descendants of Mindanao’s numerous pre-colonial Islamic sultanates. The now-gutted Marawi City is the ancestral domain of the Maranao people.

Pananadem, which premiered in March at La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club in NYC’s East Village, is what “remembering” history looks like from a Maranao perspective: An elaborate patchwork drawn from current events, ancient Maranao epics, unrecorded American massacres, and personal memories of persecution under dictatorship. It is also a story of resistance, and a promise of redemption.

Pananadem’s most transfixing scenes are the elaborate, prop-heavy choreographic sequences, variations on a dance form called singkil: Traditional Maranao step-dances performed over clashing bamboo poles, beneath twirling sequined umbrellas, and behind folding fans. The form has been popularized internationally by the Philippine National Dance Company, but in Maranao culture, these all correspond to specific images that draw together the main thematic elements of the whole performance: The bamboo dances correspond to disaster and turmoil; the umbrellas correspond to magical mushrooms and their healing properties; the fans to butterflies that will guide you home when you’re lost.

“They have a certain meaning—a lot of times relating to nature or everyday life,” says Kinding Sindaw’s Malaika Queano, who is Maranao herself and was Pananadem’s production manager. “It’s called “Remembering,” right? The main concept was remembering your strength from your heritage, from your roots.”

Pananadem, like all of Kinding Sindaw’s performances, is complex. It operates through many different narrative levels and time periods. The implicit suggestion is that to fully understand present-day Marawi and its world-historical significance, you have to go back—way back. To the outer edge of history and past it, to the point where history becomes indistinguishable from myth.

At its most fantastical level, it dramatizes an episode from Derangen, the ancient Maranao epic that UNESCO has named an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, which has been passed down through several generations of Maranaos, mainly in the form of oral chants. The episode, which comprises the heart of the performance, tells the story of cultural exchange, war and courtship between rival kingdoms in the region.

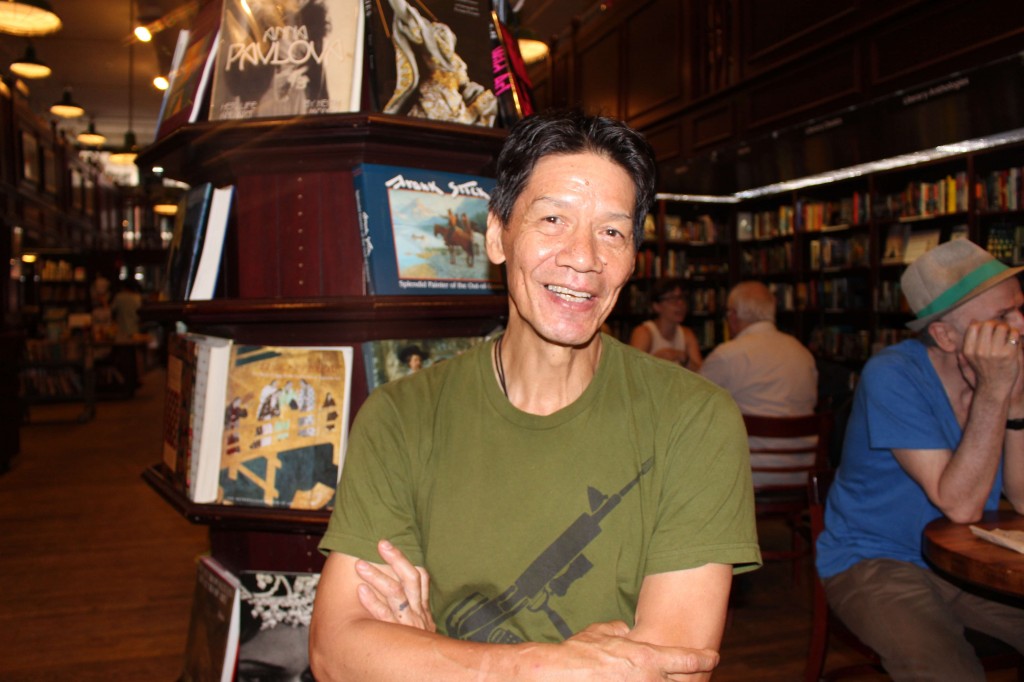

“In the Philippines, we were told that Shakespeare is the world-known poet, and you have to know the iambic form and the sonnets,” says Potri Ranka Manis, the Maranao playwright who founded Kinding Sindaw. “It seemed like nobody knew that we have our own theater form, our own epic told in the most beautiful poetry.”

Potri, who is also a NYC nurse, started Kinding Sindaw when she immigrated to the U.S. in the early 1990s. Since then, she has become something of a cultural figurehead among young people in New York’s Filipino community as both purveyor of revolutionary wisdom and bearer of an endlessly complex and little-known chapter of modern world history.

“Tita Potri has been one of the greatest inspirations for me,” says Jerome Viloria, a 26-year-old Filipino American from Rockland County, New York, who has been performing with Kinding Sindaw since February 2019. “She has the courage to tell her story, as well as the story of her people and all the disenfranchised people of Mindanao.”

“Our stories have been silenced. Our stories have been revised, sanitized according to who wants to conquer us,” Potri tells me as we chat in La MaMa’s theater seats on the opening night of the performance.

Spain conquered the northern part of what is today known as the Philippines in the 16th century, but the pre-existing Islamic sultanates that lay to the south proved strong enough, economically and militarily, to resist Spanish conquest.

That all changed when the Spanish empire fell and Spain’s overseas colonial territories, including the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam, were handed over to the United States in the 1898 Treaty of Paris. The entire Philippine archipelago was included in the negotiations—even those areas that Spain had failed to conquer.

“We were sold arbitrarily to America,” says Potri. “Our sovereign island was included in the map without our permission.”

This is why Catholicism, a cultural import of Spanish colonization, still predominates today in the north of the archipelago—the area that is, not coincidentally, still considered the cultural, economic and political center of the Philippines—while the more marginalized Mindanao, in the south, retains much of its pre-colonial, Islamic cultural character.

This is also why Malaika, who is Potri’s daughter, felt out of place growing up among New York’s Filipino American community. “If it was about food, it was about pork. If it was about parties, it was about Christmas,” she says. “And I’d always have to say that actually, I’m not that kind of Filipino—I grew up Muslim.”

But after Duterte and Trump’s presidential elections in 2016, Malaika found herself drawn deeper into New York’s Filipino activist circle, where she learned a lot about grassroots organizing but at the same time felt the cultural contradictions between herself and other Fil-Ams more strongly. “The more I was exposed to the Filipino community, the more I was seeing how my culture is exoticized—even among other Filipinos,” she says. “That, or they just plain didn’t know anything about it, because it’s not in the history books.”

After Pananadem’s opening scene of refugeedom in the aftermath of the 2017 siege of Marawi, the play jumps back in time to President Ferdinand Marcos’ U.S.-backed military dictatorship of the 1970s. A Maranao child has a message sewn into her dress that she must deliver to a neighboring village. In a harrowing sequence, she is pursued by soldiers and eventually taken captive, bound and blindfolded.

“That was based on memories from my mother. During Marcos’ time, raids were happening on a regular basis,” says Malaika, who in recent years has assumed a more active leadership role in Kinding Sindaw’s productions. If you were an adult traveling past curfew under martial law, you were assumed to be a rebel, so children were often tasked with running communiqués between villages.

Potri was taken as a political prisoner at age 13—an event that informs the structural logic of the entire show by serving as the transition into the Derangen epic. “She was blindfolded for three weeks straight. Remembering these different legends from the Derangen is what got her through it,” says Malaika.

Potri cries a little when we talk about this definitive period of her early teenage years.

She was detained in 1973 and given conditional release in 1975 to attend nursing school, reporting back to the barracks every Friday—which Potri describes as a “privilege” granted to her by one of the more compassionate guards.

“People who work for the enemy can still be good,” she says through tears. “He was on the enemy’s side—a graduate of the Philippine Military Academy—but he looked at me not as a prisoner, but as a child with a future.”

Potri says her political prisoner status wasn’t officially cleared until the dictator Marcos was ousted in 1986.

Mindanao’s history is riddled with atrocities, especially during the Marcos years, some of which are just now coming to light. This section in Pananadem also dramatizes the Palimbang Massacre of 1974, in which the Philippine Army slaughtered more than a thousand Indigenous Muslims in coastal village raids, forcing victims to dig their own graves before shooting them en masse. Only in the last decade or so, through the tireless insistence of human rights advocates, has the government of the Philippines begun to formally acknowledge that the Palimbang Massacre even happened at all.

All of Kinding Sindaw’s theater performances act as historical interventions, an archive in itself, documenting atrocities where the official records have failed to do so. As Potri walks me through the group’s back-catalogue over the years, she rattles off a series of early 20th-century massacres in Mindanao that I’d never heard of—all of which were committed by the United States.

The 1890 U.S. Census is famous for its proclamation that the frontier was dead. The population distribution of the U.S. showed that there was no longer a clear frontier line of white settlers pushing westward. The census, when compared to that of 40 years prior, also indicated that the Native American population had been wiped out by nearly half. America’s Manifest Destiny had been achieved.

Still, it was not complete. Eight years later, following the handover of Spain’s colonial holdings to the U.S. after the Spanish-American War, America’s expansionist, imperialist project extended overseas. Through brute military force, the U.S. did what Spain could not: It invaded the island of Mindanao, home to numerous highly complex and interconnected feudal-agrarian Islamic sultanates—including the Maranao.

“The Philippine-American War is an extension of the war against the Native Americans. The taking of our land is patterned from how Native Americans lost theirs,” Potri says.

“Even the guns,” she says, pointing wordlessly to the gutted prop rifles lying center-stage under the spotlight at La MaMa, which Kinding Sindaw would use in the performance later that evening. “The .45 Caliber was invented against us.”

It’s a vital episode in the Philippines’ long revolutionary lore: Historical accounts from the era tell of U.S. soldiers shooting indigenous resistors in Mindanao multiple times—in one instance, 12—before they fell. In response, the U.S. military invented a new, more powerful gun: the standard-issue .45 Caliber.

The iconic American cultural symbol doubles as a monument, hidden in plain sight, to this unjustly-obscured chapter of U.S. history.

“Years ago, I went to D.C. and asked, ‘Why is there no monument to the Philippine-American War?’” Potri says. “They responded to me at the Library of Congress that there was no Philippine-American War.”

This systematic erasure is what makes the history of Mindanao difficult to access and difficult to reconstruct—but that is exactly what Potri and Malaika are doing through Kinding Sindaw’s performances. “I’m drawing parallels,” Potri says of the writing process for Pananadem. “I’m intertwining the Maranao epic with what happened before in our history and what’s happening now.”

Activists like Potri understand the infringement by the Philippine army on indigenous land—including the 2017 siege of Marawi City—as the present-day extension of America’s genocidal imperialist project for Mindanaoan land and resources. It’s a direct, structural link: The Armed Forces of the Philippines, as it exists now, was a creation of the U.S. military.

“Colonization in Mindanao is now very latent,” Potri says. “Because you’re facing your own brother Filipinos.”

Potri’s feelings of betrayal and exasperation on this point are palpable. “The missing link of Philippine history is kept by the Maranao—the missing link of mankind,” she says, addressing her Filipino compatriots. “Martial law in Mindanao, Marawi razed to the ground—and I don’t know how much Filipinos even care. Can you really afford to destroy the last great kingdom of your society?”

Malaika, an engineer just a few years out of college who was born and raised in New York, feels a sense of responsibility as a young person who must carry the ancestral traditions of Mindanao’s people forward. Having studied under one of the few still-living masters of the art form, Malaika is a musician adept at the kulintang, the series of eight graduated gongs whose distinctive melodies thread the entire performance of Pananadem together.

“When I visited my relatives in Mindanao in 2018, none of them had their kulintangs anymore. They were in their ancestral homes, which had all been bombed,” she says. “The siege has completely destroyed all these different remnants and heirlooms. So when the siege happened, that’s when I realized my people could actually be erased in one full movement—one full swing.”

Stepping into her mother’s shoes and taking on a greater leadership role, Malaika in recent years has made more deliberate efforts to develop the political awareness of Kinding Sindaw’s membership, drawing on lessons she’s learned from other organizers in New York.

“I want our members to become advocates themselves,” says Malaika. “That’s why I began specifically programming political education that focuses on Maranao issues directly.”

It was this emphasis on Philippine political realities that drew Jerome to Kinding Sindaw after belonging to other Filipino clubs where the link between politics and culture was not so clearly defined. “Kinding Sindaw is art as activism,” he says. “It’s helped me see that being Filipino American isn’t just about ‘Filipino pride.’ It’s about doing what you can as members of the diaspora to bring awareness to the political struggle in Mindanao and other pressing issues in the Philippines.”

Pananadem ends with a dazzling martial arts sequence as the Maranao people ward off invaders from a neighboring kingdom. It’s the conclusion of the Derangen episode that inspired the production, a story within the epic whose title, according to Malaika, translates to “The Kingdom that Drips in Gold.”

“We are trying to show the parallel from the Derangen to our modern history as Maranao people,” says Malaika. “We are a people wealthy with resources, and invaders want that. They’ve always wanted that. That’s the basic concept.”

Today, the sprawling island of Mindanao still holds vast, untapped reserves of precious minerals including gold, copper and iron, in addition to significant oil and natural gas deposits. With mining companies and multinational corporations chomping at the bit for access to the island’s wealth, its people—weakened by the 2017 siege and two years of martial law—face cultural and environmental destruction.

“This is my only way of telling the world what’s happened to us and what will be lost. It is my warfront, my cultural warfront,“ Potri says, stressing that Kinding Sindaw is not only about the mere preservation of culture, but also about fighting back.

“Ours is the longest resistance movement in history, from 1500 to the current. That is my driving force.”

Amid the COVID-19 crisis, Kinding Sindaw has seen cuts to programs and sources of funding, as well as loss of livelihood for many of its members. They ask for donations here so that Kinding Sindaw can continue its mission to assert, preserve, and reclaim the epic legends and unwritten history of Mindanao.