I gazed into the gimmick, and the gimmick gazed back.

December 21, 2020

On June 2, 2020, I logged onto my Instagram account. It was “Blackout Tuesday,” a social media campaign created by two Black women music executives, Jamila Thomas and Brianna Agyemang, to “disrupt the work week” in their industry in response to the Black Lives Matter protests. Instead of the usual selfies and food pics, participants were posting a black square with the hashtag #TheShowMustBePaused. As the campaign’s website explained, “It is a day to take a beat for an honest, reflective, and productive conversation about what actions we need to collectively take to support the Black community.”

That day I had seen people on Twitter complain about the campaign. While the black squares started out under the hashtag #TheShowMustBePaused, the trend exploded far beyond the music industry, and most users added #BlackLivesMatter. With this shift in metadata, the campaign turned from a well-meaning statement into what many saw as a net loss. Many people pointed out that the campaign clogged up an important channel of communication for BLM organizers, ultimately defeating its own purpose, while at the same time allowing non-Black people to use silence, rather than money or institutional influence, as a metonym of their support of Black lives.

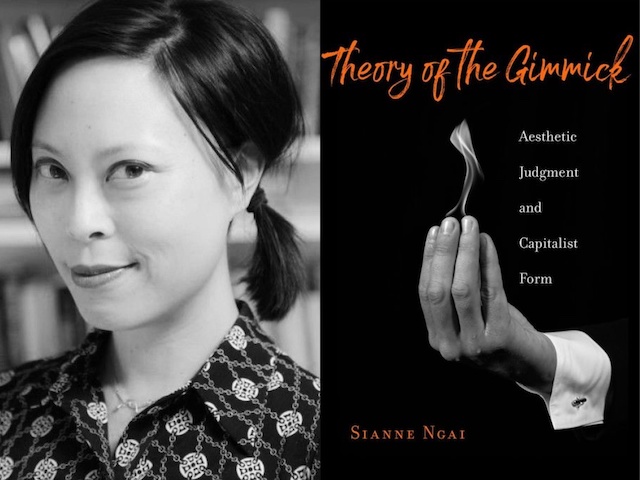

In the wake of this criticism, Instagram posts circulated about how users could quickly fix one part of the issue by removing #BlackLivesMatter from their posts and getting them out of the way. But as I scrolled through post after post of fellow non-Black people, including former classmates and coworkers, whose black squares and stoic captions read like a digital version of a presumptuous Black power fist, I felt something itching at me. I wasn’t forming a good faith critique of their interference in activist networks per se, nor of their lack of self-awareness about the historical political impact of silence. Rather, it was this collective speech act’s self-defeating nature that ensnared my attention. I found myself obsessing how the trend’s success (virality) positively correlated with its failure (taking up too much digital space). In other words, I experienced this collective speech act as a “gimmick” which, in her new book published a few days later, the academic Sianne Ngai describes as “fundamentally one thing… overrated devices that strike us as working too little (labor saving tricks) but also as working too hard (strained efforts to get our attention).”

Theory of the Gimmick: Aesthetic Judgement and Capitalist Form, Ngai’s third monograph, presents a complex cultural and political thesis, and wrangles Ngai’s newest affective concept, the gimmick, on several wide-ranging fronts: from the tricks of illusionist David Blaine to Marcel Duchamp; from the 1977 Italian supernatural horror film Suspiria to the 2014 suburban teen thriller It Follows. The book is, at first, a field guide to the junkyard of consumerist excesses—stainless steel banana peelers, Google Glass, Fyre Fest, and a loose but unifying theory of how they embody late capitalism. Ngai writes, “Our feelings of misgiving stem from a sense of overvaluation bound to appraisals of deficient or excessive labor encoded in form.” The gimmick is like a fossil preserving the compounded dysfunction, the waste, the senselessness of capitalism. To encounter the gimmick is to affectively encounter the entire system. And so, if we want to understand capitalism through aesthetics, the gimmick is our nexus.

I thought so much about Blackout Tuesday in part because my instinctive reaction to it made me uncomfortable. As a non-Black East Asian American person, and decidedly not an activist, is it really my place to have feelings about how anyone else decides to express their support? Every day, my government and its allies kill people, and not enough people care to stop it. Getting trapped in an undesirable affective pattern feels like a small price to pay for doing what little one can to speak out, right? The gimmick in this instance feels like an inappropriately petty, cosmetic judgment. “What is being accurately registered about our world… in this ambivalent, if mostly negative aesthetic judgment?… We can work our way in with a more indirect question: Why are gimmicks often comically irritating?” Ngai asks on our behalf. To begin to answer that, TOG articulates this irritation as something I have thought of as an anti-capitalist aesthetic sensibility.

In Chapter 4 of TOG, Ngai notes a connection between the gimmick and financial bubbles. She analyzes two texts, The Bottle Imp, a short story by Robert Louis Stevenson, and the 2014 horror film It Follows, in which characters must outrun a curse until they can “pass it on” to someone else, starting the cycle over again, creating an endless chain of deferred risk. She compares this series of events to the status quo of Wall Street leading up to the 2008 financial crisis, with its credit default swaps that repackaged risky investments into bundles that were then relabeled as safe and valuable, and sold off as such. She asks, “Is finance the ultimate gimmick, trapping us into either understating or exaggerating its role in capitalism writ large? This uncertainty mirrors the divided structure of the gimmick as aesthetic category: a form of appearance making aggrandized claims to value which its judgment side refutes.” If we think of the gimmick-ified version of activism as akin to its financialization, it makes sense then that anti-capitalists like myself tend to balk at gimmicky, or gimmick-employing actions using the language of activism and social justice.

When my non-Black internet acquaintance posts a black square, wears a safety pin, posts an image of their copy of White Fragility, I usually understand them to be taking part in a liberal, non-radical civic messaging, that promises “raising awareness.” While I intuitively see in their message a naive faith in the power of the media to enact social change, Ngai’s idea of the gimmick as a form of financialization suggests it has more to do with a structure of promises.

Around the same time as “Blackout Tuesday,” and in response to an even more severe instance of gimmicky activism, many Black women bemoaned what they described as “the meme-ification of Breonna Taylor,” referring to a trend in which internet users would comically tack on the line “arrest the cops who killed Breonna Taylor” to seemingly fun, unrelated posts. In one particularly offensive case, Riverdale actress Lili Reinhart posted a topless photo on Instagram with the caption, “now that I have your attention, arrest the cops who killed Breonna Taylor.” As many rightly pointed out, Reinhart’s post, and the larger trend, took part in a casual dehumanization of Taylor that people wouldn’t so light-heartedly accept if she was white or male.

As Cate Young, creator of the #BirthdayForBreonna effort to revitalize Breonna’s story on her 27th birthday, writes (in a far more in-depth treatment on this topic than I’m giving here), “For many, the proliferation of these memes feels like yet another way in which Black women are erased. Even in death, Taylor has not been allowed to stay at the center of her own story.” In the context of the gimmick, we might also look at Reinhart’s message and see something like a bad loan. It asks this cause to accept commodification now so it can hope for justice later. It condescendingly treats justice for Breonna Taylor’s violent murder as a subject that should be grateful to be smuggled into the public eye under any circumstance it can get. In a single stroke, it drives the possibility of justice into the future, while simultaneously exemplifying the embedded racism (and, for that matter, as Young’s piece touches on, carcerality) of a world in which that future can’t come. It is perhaps this temporal, contingent aspect of shallow activism that is so irritating. “Credit can also reflexively obfuscate whether it is ‘working’ or not… and therefore what temporality it in fact inhabits,” writes Ngai. Compounding promises of change further and further down the line—rather than a demonstration of commitment in the present—comprise a bubble just waiting to burst.

Reading Ngai’s work tends to feel like a two-act process. First, she lures you in with her delightful “bestiary of affects” (UF, 7) which diagnose and articulate fraught, ambivalent reactions. To Ngai, identifying a gimmick might seem intuitive, but it can be a confusing task, one that falls somewhere between ethical and aesthetic judgment… In other words, do I really judge my internet acquaintances because I think they’re falling short of enacting real change on the world (“not doing enough”), or is it because it offends my personal taste by just being kind of corny (“doing too much”)? Ngai argues that the gimmick transcends this seemingly natural dichotomy between ethics and aesthetics because it reflects the logic of capitalism, a force indifferent to both. She writes, “Our… appraisal of an object’s form as unsatisfyingly compromised triggers and comes to overlap with economic and ethical evaluations of it as cheap and fraudulent.” Herein lies the second act of reading Ngai, which is in a sense an inversion of the first: that my spontaneous, affective distrust of the gimmick belies the capitalist logics I have internalized.

Over the last six months, as I witnessed a pandemic, mass protests for racial justice, and global anti-authoritarian uprisings, the gimmick knocked around in my head, sticking and un-sticking itself to everything I took in. While pointing out gimmicky behaviors can feel satisfying in the moment, it often leaves me with an overall sense of scarcity and dread, a depressing feeling of “okay, but then what?” It wasn’t until I fully understood TOG that I realized that my impulse to identify gimmicks came not from my ideologically anti-capitalist instincts, but rather from a more base anxiety. As Ngai clarifies, “The gimmick is not only an aesthetic ‘about’ capitalism’s labor expelling drive toward increasing productivity. It indexes unease about the future of accumulation attending [productivity].” The experience of judging something as a gimmick, the thing that absurdly works too hard yet not hard enough, is the anxiety-inducing, reflexive experience of mentally calculating its value based on the unstable capitalist physics by which we’ve also been appraised for our entire lives. If we experience the gimmick as a runaway train, it’s because we’re on it.

While many of us may think we’re repelled by the gimmick because it exemplifies the success of the slick, chintzy mass production associated with capitalism, Ngai’s theory argues that we may also resent these objects for failing too much; that perhaps this repulsion doesn’t come from a desire to eradicate capitalism, but from a murkier, less rational desire for capitalism to work better. This is, I think, the central reason why talking about the gimmick is so hard. It’s a messy affective reaction that feels like a rational and critical one. To say that I find something gimmicky because I straightforwardly want to destroy its underlying capitalist logic is a bit like saying that I find something cute because I straightforwardly want to “crush,” “smother,” or “eat” it (OAC, 9). If these feelings were so simple, it would not engender so much angst to try to describe them. As Ngai states in an interview on her writing process, “The gimmick is a slippery thing… I felt like [it] was punishing me for working on it.”

Theory of the Gimmick is a book about art and literature, not activism, nor internet culture, let alone internet activism. Again, you can easily open this book expecting Ngai to dissect those most gimmicky gimmicks, and she knows this: “Why not go for a jumbosized gimmick like the one documented in FYRE: The Greatest Party That Never Happened (2018)…?… Why focus on seemingly esoteric problems?” In my first reading, I admit I didn’t fully understand the answer to this question. The theory of the gimmick attaches itself to everything you come into contact with under capitalism—why not talk about those most obvious, intentional gimmicks? But it’s clear to me now that I couldn’t stop thinking about the gimmick in internet activism (more enduringly so than other initial fixations like K-pop fancams, Our Place cookware, and Ariana Grande lyrics) for similar reasons to why Ngai focuses on art. In an interview titled Visceral Encounters she states:

Given that the gimmick form lies in wait in every capitalist commodity… and that gimmicks can be found anywhere we look…why focus on literature as the privileged place to study it? But here we should note… the infamously uncertain relation of art-producing labor to value-productive labor, raises all the same questions about labor, time, and value that the overperforming/underperforming, flagrantly unworthy gimmick does.

Unlike obvious pop culture Ponzi schemes and acts of aesthetic trickery, art and internet activism both use the gimmick at the risk of exposing their entire raison d’être to be a gimmick as well. Ultimately, there’s a lot less to say about the gimmick that cheekily declines to deny its inextricability from capitalism (fun as they can be), than about the gimmick that tries to speak directly to injustice, to cross over from the world of spectacle, to become real.

If we think of the gimmick as a risky loan, then our judgments of it within activism will always be contingent upon who we believe owns the debt, whether we think the risk will pay off, and who will take the fall if it doesn’t. The greatest question of TOG then, is not, what are the characteristics of the gimmick? But rather, who gets to use it, and to what ends? Contrary to what I noticed when first cracking open Ngai’s book, I think TOG demonstrates that it is overly simplistic to think that the use of the gimmick belies one’s secret loyalty into capitalism. Or, more precisely, it shows why it is a mistake to assume that our judgment of something as a gimmick provides us with direct access into that gimmick’s relationship to capitalism, and the capacity to then critically defeat it. “Protected by its own slickness, as a thing whose sheer stupidity cleverly neutralizes the critical feeling it incites, the gimmick defends itself from intellectual curiosity in a way that puts any person seeking to analyze it at a comical disadvantage.” The ability to identify gimmicks may not be the tactical critical skill one intuitively hopes it can be. Rather, the best study of the gimmick may be a slower, more introspective, less linear practice, one that will indefinitely ask us to fold back on our own feelings: complex and compromised as the world they live in.

Works cited:

Sianne Ngai. Theory of the Gimmick: Aesthetic Judgment and Capitalist Form. Harvard University Press, 2020.

Sianne, Ngai. Ugly Feelings. Harvard University Press, 2009.

Sianne Ngai. Our Aesthetic Categories: Zany, Cute, Interesting. Harvard University Press, 2012.