Skin too is a passport.

August 15, 2023

When you arrive in Nice, you find yourself in a country whose language you cannot speak.

Francais, once the lingua franca of the European elite, forever to you a language of empire.

A man in Paris once said if you want to hear mellifluous French go to Senegal.

The land whose inhabitants speak Wolof, you wonder. Where the French arrived on a mission to civilise and subordinate.

But all languages are colonial, your father would say. Urdu too is an imperial language.

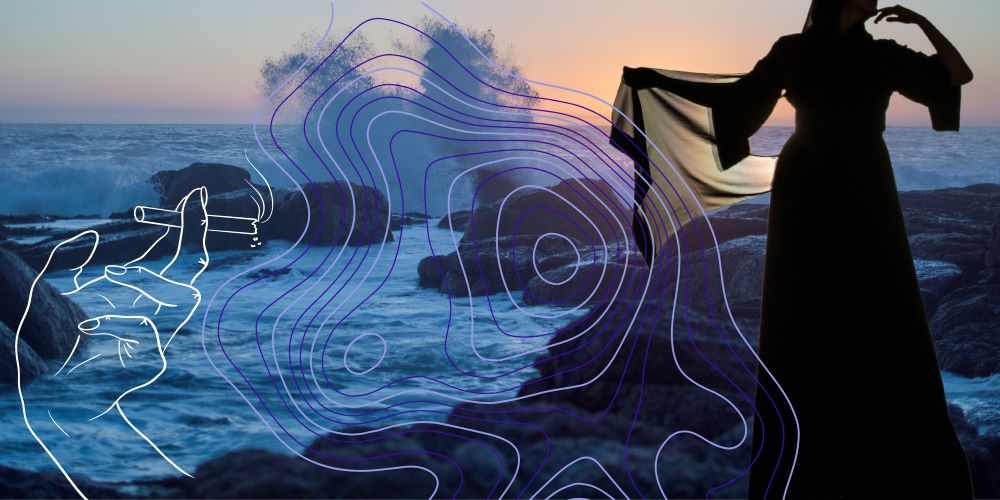

A woman in a charcoal grey abaya that trails furiously behind her in the breeze, stands on the edge of the water waving her phone interlacing French and Darija. As her grandchildren’s faces glow up on the screen, she steps further away, and soon dissolves into the distance.

Not long ago and not too far from where you stand, a woman was derobed by the police for not showing enough skin.

Unveiling women’s bodies and coercing communities into compliance. Because laïcité.

Walking along the luminous sea becomes a morning ritual. Bearing witness to the waves rolling in, rising, reclining.

The refraction of the ascending sun rendering the sea jade, lavender, silver but mostly hues of blue.

One morning you read Etel Adnan’s letters to her friend Fawwaz. There is no separation between the sea and a woman, Adnan muses. In French, the sea is a feminine noun – la mer, and the sun masculine – le soleil. In Arabic too a poem is developed along the metaphor of the sea being a woman and the sun a masculine warrior.

You were born and assembled in a city by the sea. There were folktales about the lives of those who went to sea looking for sustenance and never returned. Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai, the mystic, the poet, described a whirlpool that devoured seafarers. Fables of competent swimmers being swallowed by hostile waves. The matriarchs lamented it was immodest for women to stretch their bodies and swim in public waters for the world to see. The sea of your imagination was not a site of vastness, but of loss and alienation. The sea was decidedly not feminine.

You circle back to Adnan’s words: “To look at the sea is to become what one is.”

For thirty days the sea holds your gaze.

In the flush of the foaming waves you see the locus of longing.

Longing, which like the infinity of the sea, has neither beginning nor end.

That morning the surface of the sea ripples, the horizon uninterrupted, glittering with plenitude.

The woman with soft brown curls sitting outside the boulangerie with her crimson nails curled around a cigarette. The earthy scent of mediocre coffee. Wafts of butter. The onion-domed Russian Orthodox cathedral in the distance. The Algerian vendor who hands you a brik and refuses to take money for it. A dusty pink building in the old town you stumble upon and learn that it was home to Chekhov and Matisse fifteen years apart.

You walk into the folds of the city with a desire to roam, building a repository of memories that become cartographers over time.

Walking is your love language. Its lexicon anchored in presence and joy.

Pleasure is a place where you don’t have to fight for your joy.

Baudelaire’s flâneur walked the streets of nineteenth-century Paris chronicling the theatre of urban life. Woolf’s flâneuse was an oyster of perceptiveness. The act of wandering in her words was street haunting.

But walking in a European city in a brown body feels audacious and the pleasure often conditional.

Skin too is a passport.

Five years ago when you arrive in Tallin, the immigration officer looks up from the green passport and asks, “Reason for visit?”

“Wandering the city.”

“Alone?”

“Yes.”

He fades away with your passport in hand talking to his superiors in sounds you could not and did not wish to understand.

If you were a non-melanated woman writing the sequel to “Eat, Pray, Love”, this would not be a trespassing.

Truly, you wander to seek communion.

Communion assumes a different shape from community when you are unmoored from the land that birthed and assembled you, when you don’t believe in the nation as a constellation of imagined communities, when the restless wanderer in you knows that home is always elsewhere.

Instead, you build scaffoldings that hold space for intimacy and solitude, that cherish the mundane and banal, that find solace in markets and museums, cinemas and churches, verses and dreams.

Solitude thickens your attention. Undiluting it like a cordial that hasn’t yet come into contact with water.

You wander the streets robed in a corral of colour – fuchsia and turquoise, saffron and gold.

To be visible, in the splendour of your own skin, in communion with the city.

You step off the train from Nice to Antibes and walk towards the sea.

Two thousand years ago the Greeks arrived on this trading port they named Antipolis.

Medieval ramparts and stone fortifications wrap around the town guarding it against the sea.

You meander through the stone houses clustered on steep slopes rising from the sea, turning the colour of honey and marigold under the bright, hot sun.

The stones and rocks speak of antiquity, of lost time, of preserved time.

You remember the spherical stone tucked inside prayer mats in the homes of those you love.

That links you in prayer to the earth, to yourself, to the martyrs, to the Divine.

Perhaps, solitude is simply soundless dialogue.

That last night in Nice you sleep in the glare of your optical afterimages – the wishfilms:

The city in the waning of winter, the city on weeks where the sun doesn’t skip a day, the city on afternoons bathed in islands of buttermilk light, the city on the night the sky was a riotous pink, the city of Matisse and Chagall who captured its luminosity, the city of lengthening shadows that form filigrees, the city by the sea held in eternal blue.