In the shelter of our happiness, his shell shone brighter and brighter until one day, it split open and crumbled into dust to reveal a baby, golden skinned and blinking up at me.

November 20, 2020

After Sung Tong, a Thai folktale

I gave birth to a golden conch shell, and the palace trembled.

“I demand a son and you can’t even give me a baby?” said my husband the King.

“This is her karma,” said the monks. “She must make merit.”

“Throw it into the ocean and her too,” said all my husband’s little wives.

Everyone was so busy discussing my baby, no one spared a glance for him, so smooth and full, gleaming like a secret even in the low light. He looked like a rosebud poised to burst into bloom. He bore no chips, no cracks, no dents or dips or imperfections—there was only the shine of him, the living weight. I polished the blood from his shell.

“Sung Tong,” I said. “You will be a great king.”

With my child cradled to my breast, I could hear the wash of the tide.

Though I was sentenced to death, my husband the King took pity on me, for I was first in his heart and he had once prized me above all the wives who came after. By torchlight he led me through the palace halls and servants’ chambers, beyond the gardens and the gate, until the tree cover was thick, and the dawn broke pink between the branches, and the call of the tukae threatened to swallow us whole. Wordlessly my husband the King lopped the hair from my head. He set his nose against my cheek and trembled to breathe me in. He groped beneath my sarong, where I was torn and battered, and raised his bloody hands to his face. He left me then, and never touched his son who lay lashed to my back, patient and cool as the sea.

I carried Sung Tong in a sling through my exile, through the jungle and through each village. He grew heavier and my back bowed beneath him. I was reduced to begging—for food, for shelter, for a moment’s kindness.

“Praet,” the villagers would call me, spitting. “Beggar. Ghost.” They had forgotten the last queen as easily as they would forget the next.

When at last I found a place to stay, I was no longer a woman but a crone, my feet thick with callouses, my hands gnarled, my body the dry curl of a cotton tree root. Though our home was modest, a mere listing shack, we were rich with flowers and fruit, chickens and eggs, a clean spring and shade from the sun.

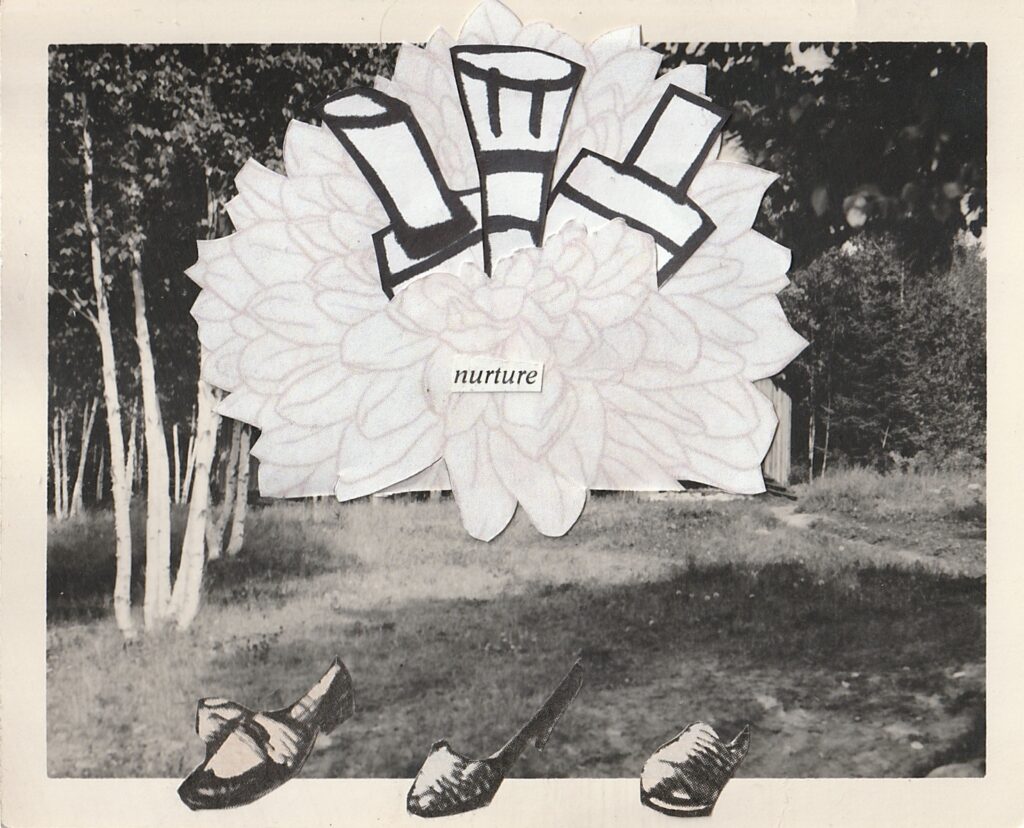

In our garden, I sang to Sung Tong every day. I rocked him, and danced with him, and told him everything he needed to know to be a kind and just king. In the shelter of our happiness, his shell shone brighter and brighter until one day, it split open and crumbled into dust to reveal a baby, golden skinned and blinking up at me.

I wiped the powder from his skin and picked him up. He was warm and soft where I had loved the cold and hard so well. I inspected his little fingers, which he would someday ball into fists. I studied his little toes, on which he would someday sprint away. He opened his mouth and cracked out a wail that would someday command armies.

When I laid my head upon his belly, I heard the drumbeat of his victories in battle. That night, I could not sleep for the absence of the ocean in my ear.