50 years after China launched the Cultural Revolution, one survivor recalls being sent to a rural labor camp and losing his family during the maelstrom.

September 30, 2016

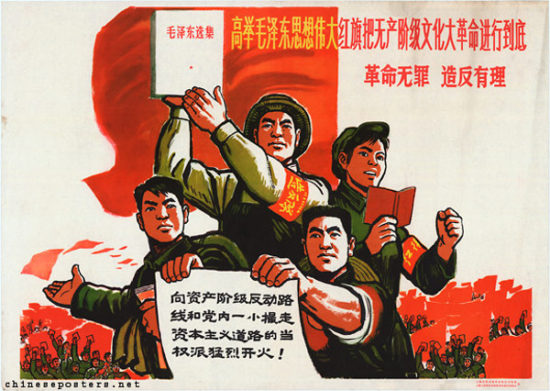

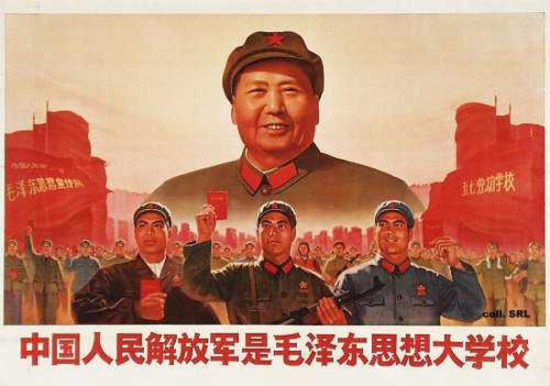

When China’s Chairman Mao Zedong launched the Cultural Revolution half a century ago, his avowed goal was to preserve the communist ideology. Mao then believed that the ruling Chinese Communist Party was losing its communist values and starting to tread down the capitalist road.

But it soon turned into a brutal nightmare that lasted for 10 years and claimed millions of lives as a result of political persecution*. From 1966 to 1976, the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution shut down schools and sent middle-class students to the countryside to work with and learn from the peasant masses. More than 14 million young Chinese were forced to lived through this chaotic chapter in modern Chinese history .

This year marks the 50th anniversary of China’s Cultural Revolution. One survivor of this tumultuous campaign, Qijian Wang, an acupuncturist who now lives in Flushing, shared his ordeal during the 10-year “re-education campaign” with Open City Fellow Rong Xiaoqing.

——————

I could never forget those days. The experience is like a haunting nightmare. Even now when I close my eyes, every single detail of the old days is still so vivid that it makes me feel chilly.

It was 1968; I was 16. I was sitting in a truck, staring blankly at the mountains nearby and in the distance. The road was bumpy. But what gave me a numbing pain was the realization that I had no idea what my future will be. I was being sent away from my hometown of Chongqing and to a remote village nestled in the Da Ba Mountain.

Mao called us ‘educated urban youth.’ But at that time, I was, theoretically, still a middle-school student. I loved studying. But school was closed and I was forced to go to the countryside. I didn’t even know whether I would be able to survive the hardship.

The village I was deployed to was a former military base for the Red Army during the Revolution. The slogans painted on the mud wall by the Red Army barracks were still visible. One slogan said: ‘Expropriate lands from the local tyrants. Distribute their farmlands.’

But all I saw in the village was poverty – extreme poverty. Some families only had one or two sets of clothes shared by all family members. Whoever went out got to dress and those who stayed at home had to be naked.

But the villagers were very kind to us, students, especially to me. My father was a banker who had worked for Chiang Kai-shek’s government*. When the communists took over in 1949, he decided to stay to help the new China establish its financial system. But when the Cultural Revolution started, he was labeled a traitor to the revolution and was sent to a re-education camp. So I became the son of an enemy. And I was often bullied and looked down upon in the city.

But in the village, the peasants never differentiated us by who our fathers were. Normally, we only got corns and potatoes for food, and the portions were far from making us full. In the rare occasions when they slaughtered a pig, they often shared the pork with me.

Still, I was wallowing in despair. During daytime, I worked at the farmland to plant crops. Unlike the villages in northern China where nothing grows in winter, the farmlands in this area are fertile year-round. So we had to work every day with no break. We had to bend down to plant rice, corns and potatoes all day long and carry water or manure in buckets from faraway to nurture the crops. We often worked in the field for more than 10 hours.

At night, too tired to even stand up, I had to deal with my hungry but hollow spirit. I tried to read as much as I could to kill time. Reading was forbidden and books were rare commodities in the countryside. Whenever friends went back to the city to visit their families, I asked them to smuggle some books for me. And I would read them stealthily by candlelight.

I read classic novels like “The Red and the Black” and “Anna Karenina.” I also started to read books about Chinese medicine and acupuncture. I was thinking that by learning medical skills, I could work as a barefoot doctor in the village, and avoid the backbreaking physical work in the farmland.

One day in 1971, when I was working in the field, the postman came and delivered a letter. It was from my aunt, telling me my father had died in the camp. It was too far for me to go back home to attend his funeral. I just settled in a quiet corner in the farm and wept alone. No one explained to us how he died. I still don’t know the answer up to this day.

In 1972, my stepmother retired. Those days, the government allowed young people to go back to the city to take over the job positions of their retiring parents. Finally, I was able to leave the countryside. Before I left, other ‘educated urban youths’ in the village held a farewell party for me. Everyone cried. I knew the tears were not only for me, but also for themselves because they didn’t know when or whether they would be able to go back to the city at all.

I started to work at the factory where my stepmother used to work. But I was far from shaking off the nightmare. In 1975, my brother, who was also sent to the countryside, died. He caught a fever in the labor work and the health service in the village was far from adequate. So he died without even being diagnosed for any specific disease.

After my brother’s death, I vowed to myself that I would become a doctor. In 1977, a year after the Cultural Revolution ended, colleges were reopened. I spent all my spare time preparing for the entrance exams. And I got scores that were above the cut-off line. I was really excited to start a new life in college. But I was told I would not be admitted because my father, although already eight years dead, was still considered a traitor. It was like the whole world collapsed on me.

I was determined to seek redress for my father’s case. The following year, I had to split my time between working in the factory, preparing for the next entrance exams and sending petitions to government officials and begging them to take a second look at my father’s case. For the whole year, I only got four hours of sleep every day. But it paid off. I was admitted at the Chongqing Medical College.

The rest of my life doesn’t have as many twists and turns. After graduation, I got a job at a major hospital in Chongqing. There, I read in a magazine called “Geography Knowledge” about the U.S. I knew that’s where I wanted to go.

I was making 50 renminbi (about $5, going by the exchange rate then) per month. I saved all my salary and used it for the TOEFL and GRE tests. In 1994, I came to the U.S. as a student of the University of Nebraska, to study substance abuse prevention.

Everyone has his or her own version of the “American Dream.” Mine is simple. Merely arriving in the U.S. is already a dream fulfilled for me. My life here in anyway is much better than my life in China. Sure, living here wasn’t easy. I had to work hard to make ends meet and to pay my tuition when I was a student. I had to find a way to get a green card so I could stay in this country.

But compared to the ordeal I suffered in China, all that I went through here is a walk in the park. If there was anything positive for me that came out from the Cultural Revolution, it is that it didn’t kill me; so it made me stronger.

I got my green card in 2000, and opened my own clinic in Flushing in 2001. My patients liked me and they referred their friends to me. I did not need to place advertisements.

Did I ever miss home and feel lonely during my early years here? No. the movement destroyed my family. Loved ones died one after another. China has nothing for me to miss.

Sometimes, people asked me whether, as a Chinese, I had ever been discriminated in the U.S. I told them, the worst discrimination I’d experienced was in China.

In the U.S., at least you make more money if you work hard and you can go to school if you like. It is a fair society. Most importantly, it gives you hope.

Hope, isn’t that what makes life beautiful?