“I’m a truck driver. Long-distance. I just came back from California yesterday.”

June 23, 2023

When Dimash began working as a long-distance truck driver, it wasn’t all bad. The pay was better than his previous gig as a delivery man for the neighborhood bakery, which had been run by Georgian immigrants. He enjoyed the scenery and being able to travel to different states. Before this job, he rarely left the security of the Soviet Brighton Beach. Every time he came back, his parents would question him about Texas, Missouri, Oklahoma. Those states just sounded so fundamentally American to them. His father would smack his lips every time Dimash told him—over tea, after dinner—about the cowboy hats being sold in the gas stations in the American south. Dimash even liked his regular partner Timur, a fifty-three-year-old Kazakh man from Uzbekistan who was obsessed with steakhouse almonds.

“We never had stuff like this in the Soviet Union,” he’d say every time he pulled out a family-sized pack of them from his worn out Adidas bag. Dimash learned early on that Timur valued things by whether he could have gotten them in the Soviet Union or not. He loved McDonalds, Adidas, mozzarella cheese sticks, and jeans.

After his second trip from New York to California, Dimash signed up for a therapy session at his local Russian community center. He knew he wouldn’t be talking to a real psychologist or psychiatrist, but he didn’t have health insurance. Even if he did, his English wasn’t good enough for an American doctor.

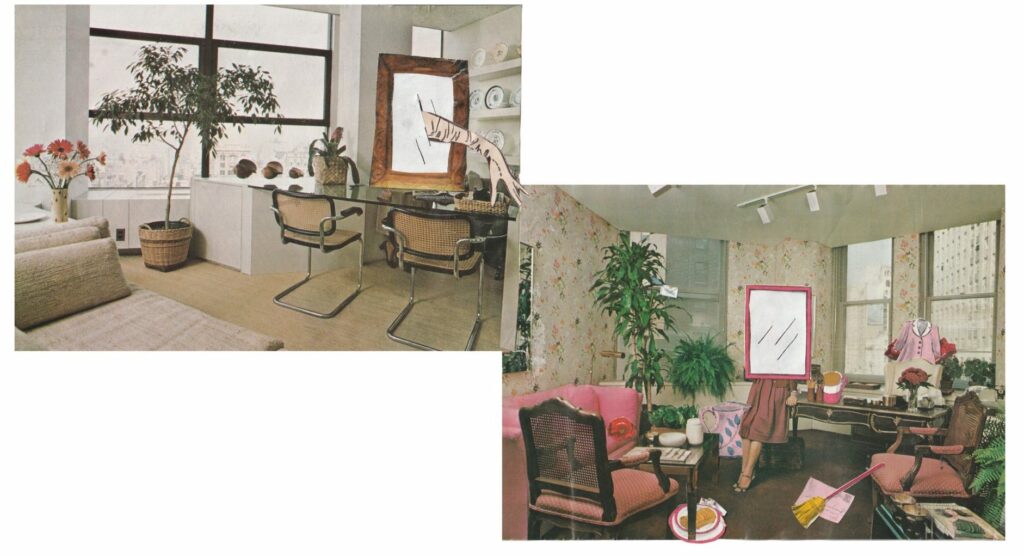

Olga Ivanova was the single community counselor, and she had an opening for that evening.

“Hi Dimash, it’s great to meet you. I don’t get many of your kind here,” she smiled sweetly at him as he sat down in her make-shift office at the back of the neighborhood public library. He smiled back, and her comment made him hyperaware of the way his eyes shrunk. He felt the familiar sense of dissociation between his body and mind creep into him but aptly shook it off and said to Olga in his native Russian, “yeah, I guess.”

They sat on opposing sides of the farthest table at the main room of the library, and while they were physically distanced from the rest of the patrons, Dimash was very much aware of how his voice traveled.

“What brings you here?” Olga asked and wrote his name down on the notepad between them. Dimash thought about telling her that she had misspelled his name ‘Demash,’ but decided against it. He didn’t want to embarrass her.

“I’ve been unhappy,” he murmured.

“How long have you been in America?” she asked.

“Three years now.”

“And how old are you?”

“Twenty.”

“Are you in school? Working?”

“Working. I finished school back in Kazakhstan. I’m Kazakh by the way.”

“I guessed. What do you do for work?”

“I’m a truck driver. Long-distance. I just came back from California yesterday.”

“Do you like it?”

“I guess. It’s tiring. I’m tired.”

“What’s tiring about it?”

“It reminds me too much of Kazakhstan.”

“What do you mean?”

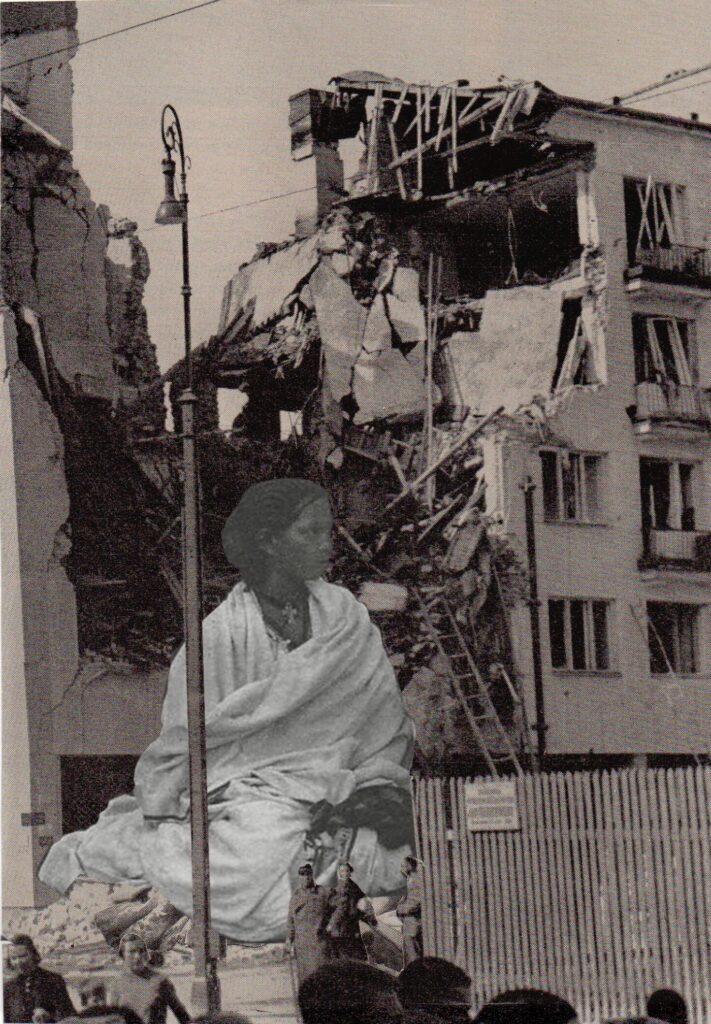

“New York City is a decoy, a lure, a fake. America is really not that much different from the Kazakh steppe.”

“I’ve never been to Kazakhstan. What makes them similar?”

“The vast emptiness on the roads. The men congregating in gas stations at three in the morning. I drink watered down coffee to stay awake for hours to just stare at more emptiness. What makes American emptiness so much better?”

“Have you thought of going to college instead of working?”

“My English isn’t so good, and my parents are too old to be working.”

“What’s so bad about America reminding you of Kazakhstan? Don’t you miss home?”

“But that’s not what it’s supposed to be, right? It’s supposed to be better. Richer? Finer? More exciting? What’s exciting about thirteen hours behind a wheel?”

“Do you have friends?”

“It’s hard to keep them when you’re on the road for weeks at a time.”

“What about a girlfriend?”

“No.”

Olga scribbled something down, but Dimash was too scared to look at it.

“And I’m tired of standing out,” Dimash said.

“What do you mean?”

“I get stared at. More than that—” Dimash stopped. He brought his hands to his collar and pulled at the fabric, feeling it get suddenly tight against his neck.

“I-” he tried again, “I get stared at?”

“Stared at?” Olga leaned forward.

“Or more like scowled at?” He brought his hands down to his lap. “Especially when I take a shower at the pit stops.”

“That’s strange. What do you think that’s all about?”

“My face, I look different. It’s like people can smell that I’m foreign.”

“But I’m foreign too. I don’t get stared at. I actually think America’s perception of us is really starting to change,” Olga said. Dimash looked into her blue eyes framed by a pair of rimless glasses and knew that she honestly believed that the two were the same.

Dimash worked as a truck driver for three more years. Olga Ivanova never saw him after their first counseling session.