One of the last newsstands in New York City is also a keeper of local lore

October 5, 2022

“What living and buried speech is always vibrating here”

– Song of Myself, Walt Whitman

(Poem inscribed at the AIDS Memorial around the corner)

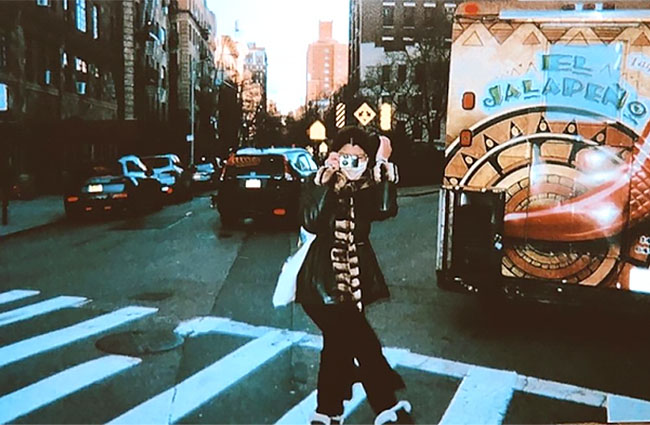

Abutting Eighth Avenue and Twelfth Street, Casa Magazines is one of the last stores dedicated to print publications in New York City. The storefront forms an acute angle at the intersection; a Greenwich Village preservation report from 1969 scientifically labeled the building “pie-shaped.” In a city where similar stores have disappeared, Casa Magazines remains. Visitors arrive from near and far, squeezing past one another to browse, and the shopkeepers are homey and hospitable.

My formal association with Casa began last October. Bodegas had just started selling chrysanthemums and a fine, misty rain chilled the air. I ducked into the store and found myself eavesdropping on the bearded, gentle-eyed man behind the till. He was speaking on the phone in Urdu. My ears pricked up when I heard his conversation speckled with “hau” and “kaiku.” These words—for yes and why—are simple but revealing. They are specific to Hyderabadi Urdu, an unorthodox, romantic dialect and my ancestral tongue. On the streets of New York, I had heard Bangla and Punjabi and Telugu and Hindi. I had heard plenty of Pakistani Urdu. But Hyderabadi? Never.

Apologizing for interrupting, I ventured a question about his origins. I was correct. Excited by our shared discovery, the man, who later introduced himself as Mohammed, promptly turned his phone around and introduced me to his young granddaughter in Delaware. He urged me to stop by whenever I wanted to practice Urdu and directed me to choose a chocolate, on the house. Thinking about my Hyderabadi grandfather’s sweet tooth, I chose a kit-kat.

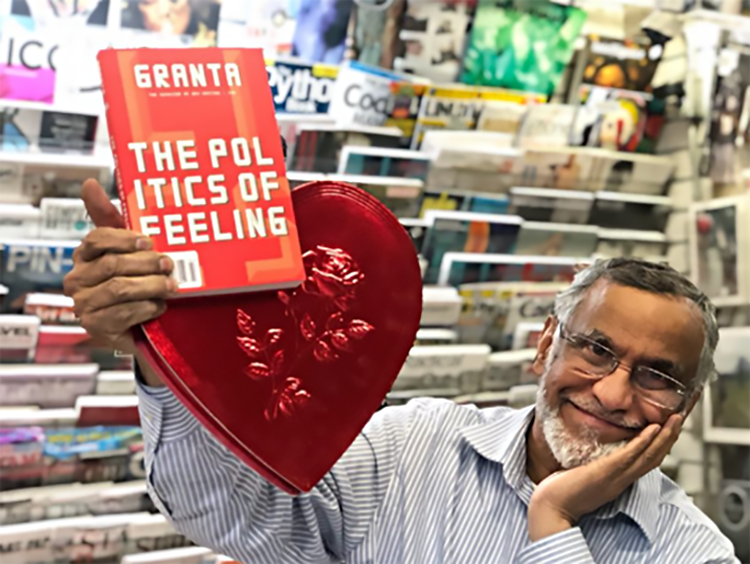

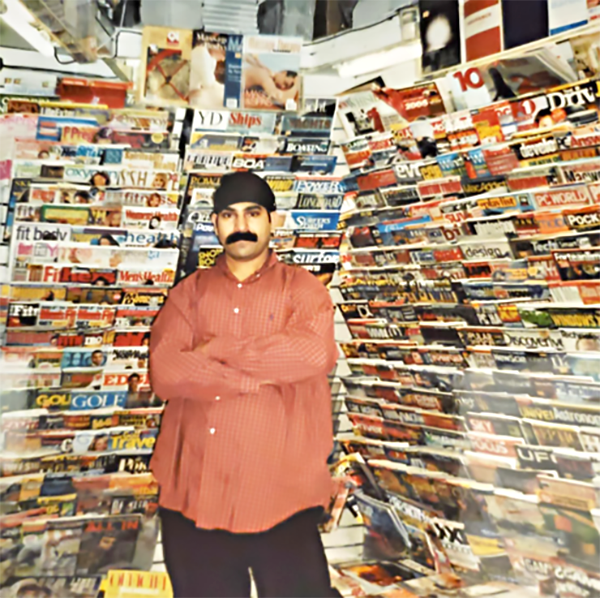

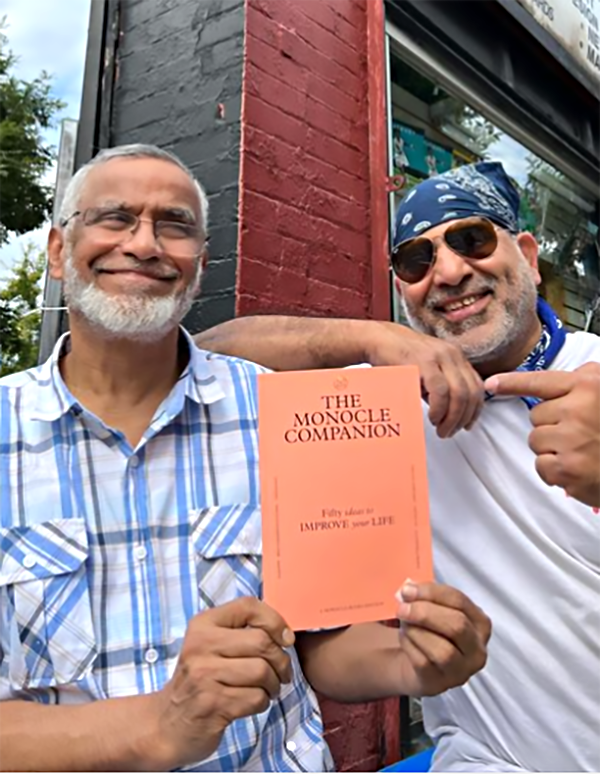

Mohammed Infal Ahmed has managed the store since 1995. He is seventy years old and the father of two daughters, a doctor and a pharmacist. He was born in Hyderabad shortly after its forcible absorption into India in 1948. Syed Khalid Wasim, who goes by Ali, is Casa’s other shopkeeper. Born in Karachi, Pakistan, he is younger—around fifty—and much more colorful, with a penchant for wearing large aviators indoors. He began working part-time at Casa in 2000 and came on full-time three years later. Beyond the magazines that line the walls (and ceiling), these men make the store a locus for stories. People are always buzzing in with news they are eager to share with the shopkeepers. And Mohammed and Ali are fiercely loyal toward their regulars, keeping up with their lives and families.

While Mohammed is the peaceable keeper of neighborhood history, Ali commands attention with his flamboyance. Hyderabad drew me into this vibrant community hub that is co-run by an Indian man and Pakistani man. As Mohammed told me, “Hyderabad Medina kehthe hai (They call Hyderabad Medina).” But it was the way one encounter leads to another, the conversations that take unexpected directions, that left a lingering impression on me. Fans of print refer to Casa as a magazine Mecca (an epithet the store repeats in its Instagram bio). If my encounter with the store started out at Medina, I landed up at Mecca, just one of many pilgrims to this shrine to print.

□ □ □ □

One snowy March day, I paid a visit to Ali at Casa Magazines. I had decided to write a piece about the store. He went outside to find his friend, Humayun, and left me in charge of the till. Humayun was visiting from Pakistan and had gotten lost. I fielded a few queries over the phone, doing my best to sound cheerful and like I had a handle on what was going on.

Then a man swung in. He had a broad smile and smooth, familiar manner. He asked for Ali and then left a message for me: “Tell him his favorite bus driver stopped by.” Without leaving a name behind, he popped back out.

I barely had time to gather myself before an elderly woman came up to the till. Moving with crisp habit, she had gone straight to the New York Times on the shelf next to the door. She counted out a neat pile of coins and slid it towards me. I, not knowing how much the print paper cost, had absolutely no idea what to do. I asked her how much she left, which was in truth the only verifiable fact in front of me. Without missing a beat, she confirmed the amount—“Just like always,” she observed. Then she went on her way.

It was as though standing behind the till at Casa conferred upon me a place in the neighborhood. Both visitors and shopkeeper placed an implicit trust in me to make sure the gears of the shop ran properly. This place seemed granted because of my shared cultural ties with Ali and Mohammed.

As it turned out, Humayun was extremely lost. The two friends, who had known each other since living in the same Karachi neighborhood as children, returned a good while later. I relayed the bus driver’s message and passed Ali the woman’s coins. Ali nodded knowingly. I had met Luis Lopez, the M12 driver. His bus route starts outside Casa and runs up to Columbus Circle. Naturally, from this alone, Luis became wrapped up in the Casa community, ensconced just as I quickly was.

Ali repeatedly assured me that I had carte blanche to ask him whatever I wanted for my piece. He extended the same privilege to my questions of Humayun. Meanwhile, Humayun jovially said to me, “You look Chinese, not Indian.” As we spoke, the two men reminisced about their childhood. Ali said that his father sent him to America as punishment for not studying.

Humayun said, “Bachpan mein main toh cricket khelta tha, aur yeh shararti (In childhood I would play cricket, and he would do mischief). He’s a naughty boy, yeah?”

Ali moved my tote bag from its slump on the floor to a hook behind the till. A neon orange pill bottle stuffed in the bag caught his eye.

“What is this?” he asked me, with the earnestness of a relative in possession of dubious medical expertise.

He did not let me deflect the conversation elsewhere. Instead, he adopted a very serious facial expression. If I ever had any problems in life, he explained, italicizing his words, I ought to come to Casa and speak to him.

□ □ □ □ □

The West Village has been home to many communities that are not necessarily reflected in the neighborhood today. From being a working-class stronghold a century ago, it is now one of the fifteen wealthiest neighborhoods in the city. NYU’s Furman Center reports that the average household income between 2014 and 2018 in the West Village’s four census districts was over $120,000. In this period, the median rent was about $2,000, over 10 percent higher than the Manhattan median and over 25 percent higher than the New York City median. Despite its layered Native and Black history, it is predominantly white. From 2014-2018, the Furman Center found that the wider area of Greenwich Village and Soho was over two-thirds white, compared to about one-half of Manhattan.

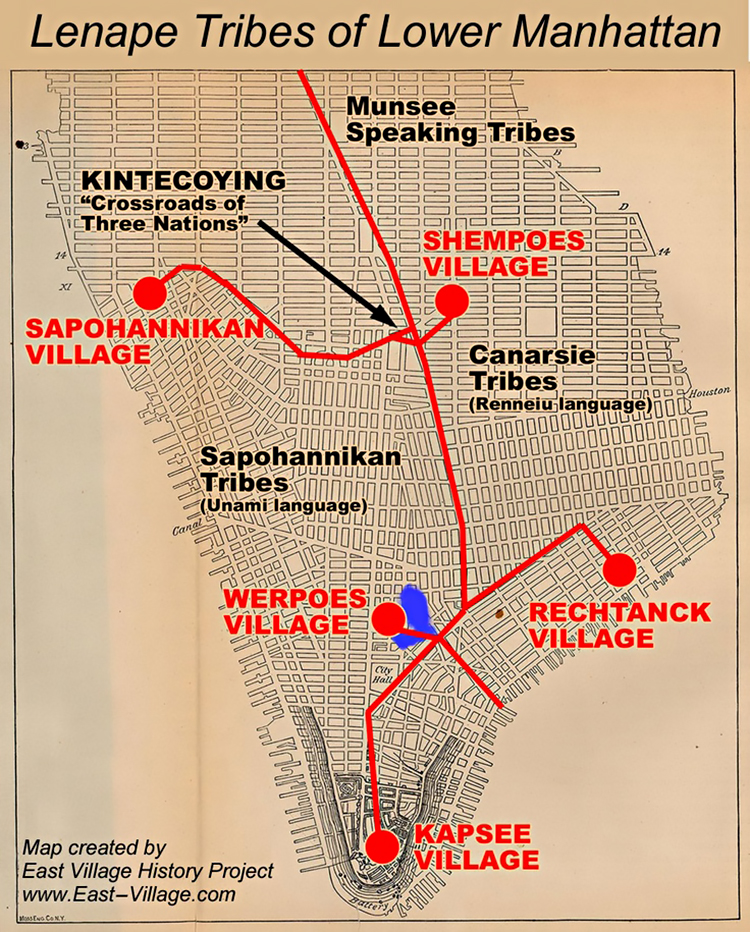

Manhattan was originally called Lenapehoking, or “where the Lenapes dwell.” Today’s West Village was part of their migration trail. In Gotham, Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace write that Lenape communities did not subscribe to a class or state system and followed matrilineal kinship. As Europeans infiltrated the area, they fomented unrest by increasing Lenape dependency on goods and arms. The Dutch, then English, trading port hugged the bottom of Manhattan’s peninsula. At the time, the West Village was a pastoral milieu.

During the colonial era, emancipated Africans inhabited an area in today’s West Village that was known as Little Africa. They built churches that have long since closed or moved. Some, like the Zion AME Church and Shiloh Presbyterian Church, which was part of the underground railroad, moved to Harlem. Samuel Cornish, the founder of Shiloh Presbyterian, helped to create the first Black newspaper, Freedom’s Journal. The first Muslims arrived in New York as enslaved Africans, and might have passed through the neighborhood.

European settlers continued to interfere with the social fabric here. In the late eighteenth century, they set up a prison at Tenth Street, on the banks of the Hudson. Black people from the Caribbean made up most of those who were imprisoned, and one-fifth of the detainees were women. Newgate Penitentiary became a tourist destination—it was the catalyst for the ferry from New Jersey. In 1829, it was closed to build the infamous Sing Sing Correctional Facility upriver.

Meanwhile, refugees fled epidemics of yellow fever in crowded downtown Manhattan and moved to the West Village. While wealthy New Yorkers nested around Washington Square Park—which began as a potter’s field for fever victims—artisans, sailors, and shopkeepers lived around the docks. Most of these Irish and Italian immigrants displaced and siloed the residents of Little Africa into tighter spaces. As the years passed, communities continued to overlap.

During the late nineteenth century, many artists moved to the West Village because of low rent. Black artists maintained the neighborhood’s rich intellectual life and sometimes pushed back against mostly white bohemians. Writer Jean Toomer, who lived on 39 West Tenth Street, found them alienating. Here, too, six blocks away from Casa Magazines, writer Lorraine Hansberry lived and published A Raisin in the Sun. In his West Village studio, Alex Haley conducted interviews with Malcolm X that became The Autobiography of Malcolm X. Greenwich Mews Playhouse focused on staging plays by people of color. W. E. B. Du Bois built on the spatial legacy of Little Africa by teaching the first African American studies course at The New School, which covered, “the development of American history with special emphasis upon the influence which persons of Negro descent have had upon the thoughts and activities of this country,” according to the university catalog. And James Baldwin, who lived just five blocks away from the Casa Magazines’ corner at 81 Horatio Street, memorialized the Village in his writing.

In Another Country (1962), Baldwin describes readers at the park: “The Italian laborers and small-business men strolled with their families or sat beneath the trees, talking to each other; some played chess or read L’Espresso. The other Villagers sat on benches, reading—Kierkegaard was the name shouting from the paper-covered volume held by a short-cropped girl in blue jeans—or talking distractedly of abstract matters, or gossiping or laughing.” L’Espresso, a popular Italian newspaper, calls to mind the European publications that line Casa’s shelves.

But Baldwin also records the racial tensions that simmered in this supposedly open neighborhood. He writes about a passerby’s reaction to an interracial couple in the same book. He says, “Since this was the Village—the place of liberation—Rufus guessed, from the swift, nearly sheepish glance the man gave them as they passed, that he had decided Rufus and Leona formed the couple.” Assumptions, guilt, and silent exclusion also marked these streets.

□ □ □ □

“You used to call me on my cell phone,” Drake’s voice blared. Ali’s phone was ringing.

It was the morning that he left me in charge of the till. New stock had just arrived, and Ali was opening boxes and organizing shelves. The busy scene posed a contrast to 2020, when the Covid-19 lockdown closed the shop and it was unclear whether it would be feasible to pay the $10,000 monthly rent.

Close to noon, a nearby deli guy arrived and asked Ali what he wanted to eat. I asked Ali if he paid for the food. He regarded me as though the idea were ridiculous and extended the invitation to me. Hands numb from the cold, I requested a tea. When I declined milk and sugar, the two men looked at me like I was an alien. A few minutes later, I was sipping a hot tea, color slowly flowing back to my fingertips.

Did Ali often get food from the deli? He said he did not. Between tracking down his friend Humayun and the early start, he had only slept for two hours, and did not have time to pack lunch. But, in a pinch, the food was there.

This was soon after I received the Open City fellowship, and I told Ali that my project stretched from February to October.

Impatiently, he replied, “Oh, you’re saying nine months, nine months, are you making a baby plan?!”

When I met him in the summer, he wasn’t pleased that the article hadn’t published yet. I felt taken to task. Ali reminded me how many publications were rushing to write about the store. Then he gave me a recent issue of Esquire with a profile of Casa Magazines as “a gift.” Ali is both zany and familiar. I wondered if his grumpy present also stemmed from our common background.

That day in March, we went from discussing my potential reproductive plans to the meaning of home. “‘Casa’ ka mane ‘ghar’ (‘Casa’ means ‘home’),” he said. I wanted to know more. He threw the question back and asked, “Ghar like New York City; home like home?”

Then, with a tinge of fatigue, he said, “Home is like as long as you finish your job, no matter like twelve-hour, eighteen-hour, sometimes I work more than sixteen hours, right? So my thing is like I go home to shower first”—Casa’s landline interrupted—“watch TV, play with the kids, and after a little while I go back—Hello?”

□ □ □ □

The rotating shop windows at Casa Magazines, facing west on to Eighth Avenue and south towards Twelfth Street, are like a public museum exhibit. Ali, who has a creative bent, curates them weekly. One week, a striking cover repeats across the glass pane. Other weeks, the windows are a teaser into the motley mix within.

A video featuring Mohammed and Ali seated against a wall of magazines at their store played at a June MoMA research symposium called “The Store and the Street.” Paola Antonelli, MoMA’s director of research and development, spoke about how shop windows are an interface between shops and streets. “Especially in New York City, artists were involved in the making of this particular membrane,” she remarked. While many look forward to Macy’s and Saks’ holiday window displays, Casa’s might represent the city better.

In the digital era, physical objects have more weight when so much consumption is ephemeral and intangible. Print, which feels precious and alluring, is a more curatable artifact than clothing, which causes more environmental damage than air travel and shipping combined. In this way, Casa is also a membrane between store and museum.

Antonelli suggested that shops are markers of vibrant cities around the world, from Tokyo to Reykjavík. “In many of these places, many of these stores, people were not really going necessarily to buy. Sometimes, it was just to hang out, just to look at others, it was to be looked at, it was about generating this kind of buzz and new creative ideas that could then proliferate in the world.”

Casa is a unique space to look and learn. Beyond the shop windows, Mohammed and Ali are living repositories of local lore, and a few minutes of people-watching is unfailingly productive.

□ □ □ □

Like lots of other parents, Ali positions himself against the defiance of the American teenager as he sees it. He told me, “I don’t want like, we come to America, and the kids, the pant is down and hang around like yo-yo. I don’t want it. Got it?”

But Ali clarified that scaring kids into obedience should be a method of the past.

“The time is over now. Respect,” he said.

A Black customer was browsing magazines. Ali pointed at him and said, “See this guy, I respect him.” I was not quite sure that this had anything to do with raising children.

The man turned around and said, “How you doin’, bud.”

Ali cocked his head and bragged, “I’m one of the gold mine locations, right? So everyone in this neighborhood is all about reading books and magazines.”

The customer raised an eyebrow and said, “It’s funny, I live in Harlem. I come all the way down here to see you guys.”

Ali thanked him, pivoted to me, and grandly declaimed, “You see this guy here, came from Harlem.” It struck me that his opportunistic rhetoric was rather American.

□ □ □ □

Casa Magazines also had a front row view of the HIV/AIDS epidemic starting in the 1980s. St. Vincent’s Hospital—the site of the first AIDS ward on the East Coast and the epicenter of the AIDS epidemic in New York—was just a few minutes east via Twelfth Street. Pre-1994, Casa may have been called Wendell’s after its proprietor at the time and been an important part of the gay community. A commenter on the New York Times’ 2021 profile of Casa wrote, “Wendell’s was a fixture, providing community to the gay population. As the AIDS epidemic took hold in the village you saw less and less of the regulars. Wendell also succumbed.”

St. Vincent’s has since been torn down, its memory enduring in a public square whose ground is inscribed with Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself.” The words wind around a fountain, and pedestrians must walk in a widening spiral to follow them. The poem is an ode to New York City, the expansiveness of its collective spaces and the distinct personalities that people them. Around the corner, Casa feels like an outpost of this sensibility, carefully tended by two Muslim men.

Another Times commenter said, “I had a conversation with Ali one day about the nursing home where my mother lived and how the residents had little reading materials. He would collect copies of magazines that passed their display date and bundle them neatly for me to take to her. And then he would thank ME for going [sic] such a good deed.”

I like to imagine a similar flow of reading material from the store to St. Vincent’s—stylish, irreverent magazines bolstering the spirits of those without enough community support.

Just when the city began healing from trauma of the AIDS epidemic, the urban landscape tore again. Mohammed witnessed September 11 from his shop. “Yahan par tha (I was here), in the morning, jab saara saamne hua tha, jab log aake bole (when it all happened right in front of me, when people came in and said), ‘What are you doing inside? Go out. Look at outside.’”

He looked up and saw the third plane hit the towers. After that, police shut off the area south of Fourteenth Street. “Yahaan aane nai diye. Mushkil se aake diye the. Aur woh kaafi doh-theen maine disturb hua business (They didn’t let us come back here. We returned with difficulty. For two, three months, business was very disturbed),” he said. Almost two decades later, Covid-19 would cause the store to briefly close a second time.

Authorities brought September 11 casualties to St. Vincent’s Hospital. Mohammed described them putting bodies on the road outside, roughly where the AIDS memorial now is. “Kya hua kya patha nai (I don’t even know how it happened),” he said, “It was a bad incident.”

After witnessing this harrowing event, he faced Islamophobia in the city. “That is the reality. Musalmaanon ke liye kharab hua. Abhi tak bhi chale hua woh (It became bad for Muslims. And it is still going on).”

I asked how it was after Trump was elected. Mohammed smiled. “New York mein aane nai diye the (They didn’t let him set foot in New York).”

But prejudice doesn’t adhere to borders. India is now the real source of worry, and we exchanged notes on the desperate political situation in our homeland. “Woh sab saara control BJP control karre. Law and order bhi control karre, courts bhi control karre. Ministers poore eki chalare. Hitler waali daur chalri wahan pe. (The BJP controls everything. They control law and order, they control courts. The ministers are all in their hands. They’re running an era like Hitler’s.)”

As the BJP, or the Bharatiya Janata Party, under Narendra Modi clinically unfolds disaster upon disaster, I don’t think it is a stretch to find hope in Casa. Amid hyper-nationalism and threats to press freedom, what else could a magazine store co-run by an Indian and Pakistani be? In their own quiet way, Mohammed and Ali continue the West Village’s history of standing for an expanded vision of the subcontinent.

After all, Roger Baldwin, the cofounder of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), lived a few blocks away from Casa. He met freedom fighter Sailendra Nath Ghose while in prison. Upon their release, they set about organizing American advocacy for subcontinental independence.

□ □ □ □

One customer asked Mohammed if we were related. “My cousin,” he replied.

There is no being objective when writing about Casa Magazines. It was funny and sweet that Mohammed lay familial claim to me. Was it a shorthand, conveniently explaining my presence by way of kinship, or a genuine expansion of the family tree? (Earlier, he had said that his cousin owned Casa. If I was his cousin too, what did this mean? I had no idea.)

Mohammed bantered with and mock-scolded the customer. “You don’t believe in God, why do you say, ‘Swear to God’?”

In February, on my birthday, I found my feet taking me from Midtown to the West Village. Incidentally, I was born the same year Mohammed joined Casa.

“Mera janamdin hai! (It’s my birthday!)” I said.

It was around lunchtime and Mohammed was handling a steady stream of clients at the till. I relaxed into some people watching. Happy David, a friend turned social media coordinator for Casa, told me, “It’s like a mini-New York, really.” Each visit illustrates that further.

I stepped out of the shop. Mohammed bellowed my name. I halted.

“Do you want anything to drink?” he called out, ever attentive.