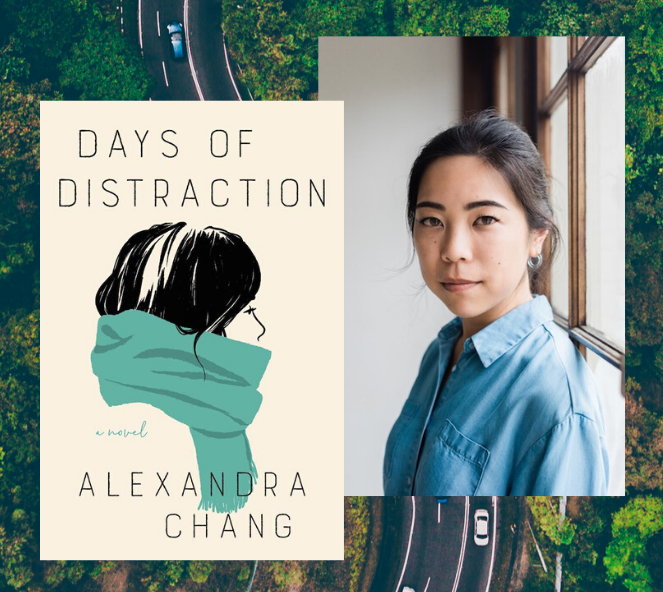

The author of Days of Distraction on microaggressions in fiction and writing confrontation through fragments

June 3, 2020

Alexandra Chang’s sophisticated and compelling debut novel, Days of Distraction, follows a young Chinese American woman as she becomes aware of the emotional and psychological complexities inherent in her long-term relationship with J, a white man. The novel explores the tensions that arise with wit, pathos, and candor.

Days of Distraction’s narrator (also named Alexandra) is an early-career tech journalist reporting on Silicon Valley. Dissatisfied with work and frustrated with what she feels is professional limbo, she decides—despite anxieties of becoming a trailing partner—to follow J to small-town Upstate New York, where he’s been accepted to graduate school. The two embark on a cross-country road trip to New York while Alexandra reckons with isolation from her family, friends, and once-familiar routine. Alone with her partner, Alexandra begins to see more clearly the disparity of the histories they embody.

The novel is written in fragments that move between past and present, between narrative and meditative modes—a structure that cleverly evokes the fractures that the narrator has begun to identify in her romantic life, the story of her family’s immigration, the history of interracial relationships in America, and stereotypes of Asian American women in the Western world.

Since its debut a little over a month ago, Days of Distraction has been critically lauded: Porter Shreve in the Washington Post writes that the book “brims with the predicaments of our current moment” and “offers a lens into the culture that allows us to see both our time and ourselves in new and striking ways”. And Sulagna Misra muses in Vanity Fair that the novel “stands out as a deep-dive into the agonies of an interracial relationship.”

Recently, I spoke with Alexandra on the phone to discuss the novel’s fragmented form, the line between autobiography and autofiction, and the ways in which her fiction grapples with complex questions of love and race.

—Michael Prior

Michael Prior

One of the many things I admire about Days of Distraction is how you’ve adopted the vignette-based structure of books like Why Did I Ever by Mary Robison and So Many Olympic Exertions by Anelise Chen in order to explore what Cathy Park Hong calls the “vague, purgatorial status” of “Asian Americans in the popular imagination.” Particularly, the ways in which this status is refracted within an interracial relationship. Could you speak a little more about the use of this?

Alexandra Chang

It wasn’t a conscious decision when I first started the book. I was initially drawn to writing in this fragmented form based off of its ease and malleability. As I worked on the book more, I realized the form could be developed and I could be more conscious and deliberate about using these fragments to dramatize a certain type of experience—the experience of a young Chinese American woman who is struggling to find a sense of self. This fragmented form is also good for capturing a narrator who is going through some sort of transition, and who is having a hard time in that transition.

I definitely agree with what you’re saying about Cathy Park Hong, that bit about the purgatorial experience of being Asian American. There are these moments where the narrator finds a momentary sense of peace or clarity, but then lapses back into shame and doubt and silence. Even when she’s aware of a certain situation, she can’t necessarily escape it. And that’s something the fragmented form does a really good job of dramatizing. A concrete example is when she attempts to have these conversations about race with her white boyfriend. They get to the edge of having a conversation, then it drops off and we enter a white space, which is like a silence, then it moves on, then later there might be a return to an attempt at the conversation. It’s this movement between confrontation and silence.

MP

I like that you bring up confrontation and silence as being something that the form enables or dramatizes for us. I think about the moments in the novel when J and the narrator have an argument and the vignette just ends—nothing’s resolved and we’re left with the whitespace of the page. I’m also thinking about how, later, the narrator begins to research other Chinese American women and the history of interracial relationships in the United States—people like Yamei Kin and Pardee Lowe. From that point on, the novel introduces a range of outside documents like newspaper articles and sociological studies addressing historical conflicts and silences.

The narrator really gets drawn into this research—to the point where it begins to have a notable effect on her relationship with J. I get the sense the narrator’s trying to construct a lineage for herself and her relationship, a lineage that’s going to help her figure out who she is and how her relationship with J fits into forces of history and race in America.

AC

The form naturally enables this injection of outside sources. Maybe in a more traditional novel you’d have to explain each instance of a historical document appearing in the text. I always knew I wanted some sort of historical element to come into the book, partly because I knew it would feel claustrophobic to me, to be in this one narrator’s perspective the entire novel. Bringing in historical elements was one way to expand the narrative beyond her.

You’re right. It’s an attempt for her to develop a lineage, to develop a sense of her identity through studying these historical figures who may or may not have had a direct influence on who she is today. As she becomes more isolated in her life, she grows increasingly obsessed with seeking answers in her research and especially through people with whom she identifies some connection. Both Pardee Lowe and Yamei Kin were married to white partners, and through them she’s seeking different answers on how to be in her own relationship. She’s also feeling lost, and in the process of unearthing and discovering these people’s stories, which are also largely lost to history, she’s hoping to gain some sense of footing.

MP

I saw on some of the early promotional material that George Saunders compared your novel to Claudia Rankine’s Citizen. At first, this struck me as a surprising comparison. I thought your novel was doing something very different than Citizen—and of course, in many ways, it is—but then I realized that in Days of Distraction, like in Citizen, there are a lot of moments in which the narrator struggles to interpret interactions that, in retrospect, are clearly microaggressions; I thought of that question that repeats throughout Rankine’s prose-poems: “What did you just say?”

AC

AC: I read Citizen around the time that I first started writing this book. There are sections of that book that were definitely influential in writing the vignettes where the narrator encounters microaggressions. What I loved about that first section in Citizen is that Rankine is able to succinctly capture this sense of confusion and shame and questioning that a Black person feels in those encounters. That’s something I have also felt as an Asian American woman.

A lot of the moments in my book where those microaggressions take place are within the narrator’s most intimate relationships. It’s especially fraught because those microaggressions and misunderstandings are coming from people who the narrator feels know her really well and who she feels she knows really well. For example, J saying something like, Oh, it’s not a big deal, what you just went through. You’re overreacting. There’s this huge gap in their experiences and understandings of the world, and in those moments, that gap feels very extreme to the narrator.

MP

I think you’re referring to one of my favorite passages on page 213, when J dismisses the narrator’s recognition of the racism implicit in an awkward encounter with a white professor who encourages the narrator to apply for a job at her college, and then proceeds to discuss the “Asianness” of various places in America. Later, J and the narrator argue over whether the professor’s comments were problematic, and the narrator realizes:

“The silences between our words extend further, there are differences neither of us wants to traverse as though going from where one stands to where the other stands is to break from an essential part of oneself. And if both of us remain as firm in our positions, then what? Is it possible both of us are in the right? I doubt it. I won’t go there.”

It’s a powerful passage, and I think sums up much of what the book is doing in terms of its thinking. As you say, some of the most racially fraught moments in the novel occur within intimate relationships—such as the one the narrator has with J, but also with other characters, like the narrator’s friend, Jasmine, or even family members. There’s an incredibly moving moment where the narrator asks her sister what it might mean that they are both dating white men. I’m also thinking of an even earlier moment when the narrator is visiting a high school friend in Portland who offhandedly says a bunch of things, which makes the narrator reconsider the racial dynamics of her whole high school experience.

AC

Right. Those moments are especially frightening. When you’re with somebody who you feel safe with, because you love them, you’re not expecting them to hurt you. Whereas when the narrator is traveling across the country, she’s very on guard. She’s waiting for something to happen as she’s traveling in these very white spaces. The unfamiliarity heightens her sense of fear, of paranoia. The microaggressions and racist comments from friends and family, those come when the narrator is more open, and therefore vulnerable.

Thank you for reading that passage because I do agree that’s a pivotal moment in the book, where the narrator really starts to question why she is in this relationship. She starts to put herself on guard around J, which is an unpleasant feeling for her. And she asks herself, Is it possible to be in a relationship with somebody who has such a different experience of the world than I do?

MP

Near the end of the novel we learn that the narrator’s name is Alexandra; it only takes a cursory glance at the novel’s acknowledgments page to see that the names of many characters are the names of real people in your life, which of course suggests that the book might be autobiographical, or perhaps autofictional. Could you talk about your relationship with autofiction and if that particular genre—term, lens—was part of how you approached the book?

AC

I love a lot of the books that are categorized as autofiction, like Rachel Cusk, Elena Ferrante—which is a weird label for her since we don’t really know what Ferrante’s life is like. I read the first Knausgaard and enjoyed it. But autofiction as a term is confusing, because I’m not always sure what people mean when they bring it up. It seems like it’s not very well defined. So I’m curious what you think autofiction is. Like, what is the difference between autobiographical fiction and autofiction?

MP

I mean, my limited understanding is that the genre itself is rather porous—maybe right now it’s as much defined by how a publisher wants to market a book as anything else? It seems like it has something to do with a kind of writing that is heavily autobiographical, but still allows itself a certain “factual” leeway. The narrator often shares the author’s name, and is often engaged in writing the very book we’re reading.

AC

Hmm, I do like that definition. I’m always curious what others think of autofiction. Oh and I thought of another writer I like who gets categorized as autofiction a lot: Sheila Heti.

Anyway, I started this novel as a document where I was putting down these bursts of musings and scenes and thoughts and character sketches, and they happened to be drawn from my own life. I also gave myself a lot of the leeway to fictionalize on the sentence level, and stylize scenes and characters and thoughts however I wanted or needed to for the story—but once I did start writing material drawn from my own life, I felt this impulse to continue doing that. It felt strange to start writing completely fictional things. Granted, there are a few characters in this book that never really existed as they are. But it felt important to me, at least, to maintain this relationship to the narrator once I started.

The questions about interracial relationships, the questions about Asian American identity, and Asian American experiences and history, and how that affects day to day life for a modern young Asian American woman—those are all close to me, so I had this resistance to straying too far into the fantastical or totally fictional. But then again, there is a lot that strays from reality, memory, or even what I really think or believe as a person today. And there are moments where I try to call the world of the book into question, too.

MP

Now that the book’s out in the world, what makes you nervous about its reception?

AC

AC: This is related to the question about autofiction, which is that someone will read this book and think it’s memoir: this narrator is the author and everything she says and does and thinks is what the author says and has said and done and has thought. That is not true. We don’t often talk enough about the fictional aspects of autofiction. For me, the narrator is a dramatized version of myself, who through that dramatization feels distant and separate from me. I thought of her as around 20 to 50 percent more dramatic and neurotic than myself, even though I have had a lot of the same questions and fears that she’s had. I think essays or memoirs about these questions typically try to offer answers or takeaways, but the world of fiction, at least the fiction that I like, does not.

Another thing—not that it makes me very nervous—but I know that the book is not going to satisfy some readers. A reader who is seeking a faster-paced book or a reader who’s seeking a character who has a major transformation or a reader who wants a really satisfying ending, where things are resolved. None of that exists in my book. So I’d say, if you are needing that from a book right now, this isn’t the one for you.

MP

I think the book pushes against the questions it sets up for itself, and acknowledges that there’s no way to arrive at satisfying answers—at least if it’s going to be honest in its inquiries. Was there anything you discovered while writing Days of Distraction that changed your thinking about some of the issues the book explores?

AC

In my own life, I can’t recall ever having a big transformative moment or moments where, suddenly, everything felt resolved. I feel like growth and change comes in pieces, and it’s not always easy to tell when it’s happening, or even look back and pinpoint when you changed.

I did learn that writing a novel is hard and time consuming. And I learned that writing about these kinds of questions, especially about being in an interracial relationship, and the anxieties and fears and questions around that—it is really difficult. It’s difficult to interrogate that relationship, even in the fictional realm, when it closely resembles a real-life relationship. I won’t go too into detail, but I found writing those sections affected my perception of my actual relationship, even when the relationship in the novel did not line up with what was happening in reality. So not only is writing a novel hard, just on a logistical level, but it really affects your psyche in your day-to-day life.

MP

I’m mixed-race: I have an Asian mother and a white father, so reading the novel for me was a harrowing experience in different ways because I was thinking about questions I haven’t asked, things I wish I asked my parents earlier, or things I wish I felt brave enough to ask them now.

AC

AC: In our day-to-day lives we don’t necessarily have the time or the space or the courage to ask those questions. But one great thing about writing is that you have that time and space to explore the questions that you’re scared to ask.