For some of us, a food is not something we can so easily cast aside before finding a new fad to follow.

August 21, 2019

When I moved to Madison, Wisconsin five years ago to attend graduate school, I found an inexpensive apartment on the edge of town. This means that every time I want to get to campus, I now wait at a bus stop that sits in front of a small farm. Because I grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area, it pleases me that this bus stop allows me to do what I once thought was only a figure of speech for the quiet solitude of the American Midwest: I get to watch the corn grow. In June, the green stalks shoot up from the dead ground so quickly that it feels like I’m watching a time-lapse video. By August, the corn will be so tall that I’ll have to run out into the street and wave to the bus before it flies by me. “I’m sorry,” the driver will say, “I couldn’t see you there behind all that corn.”

Of course, this doesn’t happen every summer. Every other year, soybeans grow on the farm, suggesting none of the same dramatic American excess. It’s a practice that dates back to the early twentieth century, when the African American scientist George Washington Carver, a former enslaved person, discovered that alternating cotton with soybeans could help prevent the depletion of nitrogen and other minerals from the soil. Today, Midwest farms like the one by my bus stop rotate their crops: corn one year, soybeans the next, and so on.

I started to pay more attention to the soybean years when I began researching my grandfather. Not the grandfather on the side of my family from Japan—where the soybean is a dietary staple—but the one on the Hungarian side. An immigrant to the United States in 1919, my paternal grandfather Francis Kalnay was an award-winning children’s book author, a CIA officer accused of communist espionage, and an early champion of soy foods during a time when many Americans were still wary of eating a plant that seemed foreign and ersatz, better suited for feeding pigs. In a May 1959 issue of House Beautiful, a popular home-making magazine, I found an article he wrote under the title “The soybean has all the answers (or nearly all).” As I sat in a musty library basement one afternoon and read the article’s rhapsodic language (“Cultivating soybeans in your garden is like cultivating health and fun”!) and recipes for dishes like “Paprika Liver and Soy,” I was struck by this strange confluence of the two sides of my ethnic heritage.

My grandfather writes, “In our country soy is relatively new. But in its native Asia, for millions of people for many centuries, you might say soybean is not only a bean, it is also a ‘cow’—the sacred cow of the Far East.” He claims that soybeans provide “almost anything the body wants and needs: growth, heat, energy, and constant repair” while affording “a fountain of flavors.” His euphoric praise of soy prophesizes fad diets like macrobiotics, which would take off in America only later, by around the late 1960s. Yet, despite how common vegetarianism and veganism are today, I still often hear soy described in similar exoticizing terms. For some Americans, soy checks off many of the qualities that mark the Oriental: Strange and alien, soy is either artificially idealized as a “superfood” (“it will cure you”) or regarded with suspicion (“it may secretly be making you fat”). Either way, soy continues to be demoted to a secondary ontological status. It tends not to be seen as a “real” food, but merely a replacement.

I grew up half-Japanese during a time when tofu and other soy products were something my non-Asian friends considered gross, and something their parents only consumed with a sense of self-sacrifice, as a fringe health food or protein substitute. In the 90s, the kids in the lunch yard sipped Capri Sun from glittering metallic pouches and stained their fingers neon orange with Cheetos dust. I begged my mother to pack me these tokens of acculturation, but at home, I still loved to eat sticky rice topped with natto, tough and slimy fermented soybeans, or cold tofu drenched in soy sauce. Today, my family continues to keep a large bottle of Kikkoman in the cupboard that we use to refill a little plastic canister with a green cap. This canister is the kind of inexpensive item you can buy at a 100-yen store, the Japanese version of a dollar store, but we have held onto the same one we had when I was a kid.

A year or two ago, I had dinner at a professor’s house with some fellow graduate students, all of them white and American, and the conversation turned to soy. We were eating zucchini noodles with homemade pesto and roasted sweet potatoes. Someone mentioned that she had started to avoid soy foods due to their harmful health effects. Similar statements had started popping up in headlines on my Facebook newsfeed—“What Is Tofu? 8 Reasons to Not Eat This ‘Healthy’ Vegan Product” and even “Soy Is Making Kids Gay.” (As one of my gay friends observed in response, “And that would be pretty great.”) This time, however, the statement made me pause. While it gave me no offense (it did not even register on the scale of culturally insensitive comments I had heard), I was perplexed that she thought of soy as little more than a dubious health food fad. Soy has for centuries been a dietary staple, not only in other regions of the world, but in Asian communities here in the United States. How can a crop that is so pervasive across America’s “heartland” still seem so indigestible?

*

In “Jack and the Beanstalk,” a boy trades a cow for a handful of “magic” beans. When his mother admonishes him for giving away their family’s only source of sustenance in exchange for something she deems worthless, the boy throws the beans out the window. Overnight, they grow into a giant beanstalk that stretches up to a castle in the sky. In many ways, this fairytale could be read as an allegory for the American history of soybeans. Both are stories of trading milk for beans—stories of devaluation, appropriation, and unlikely flourishing.

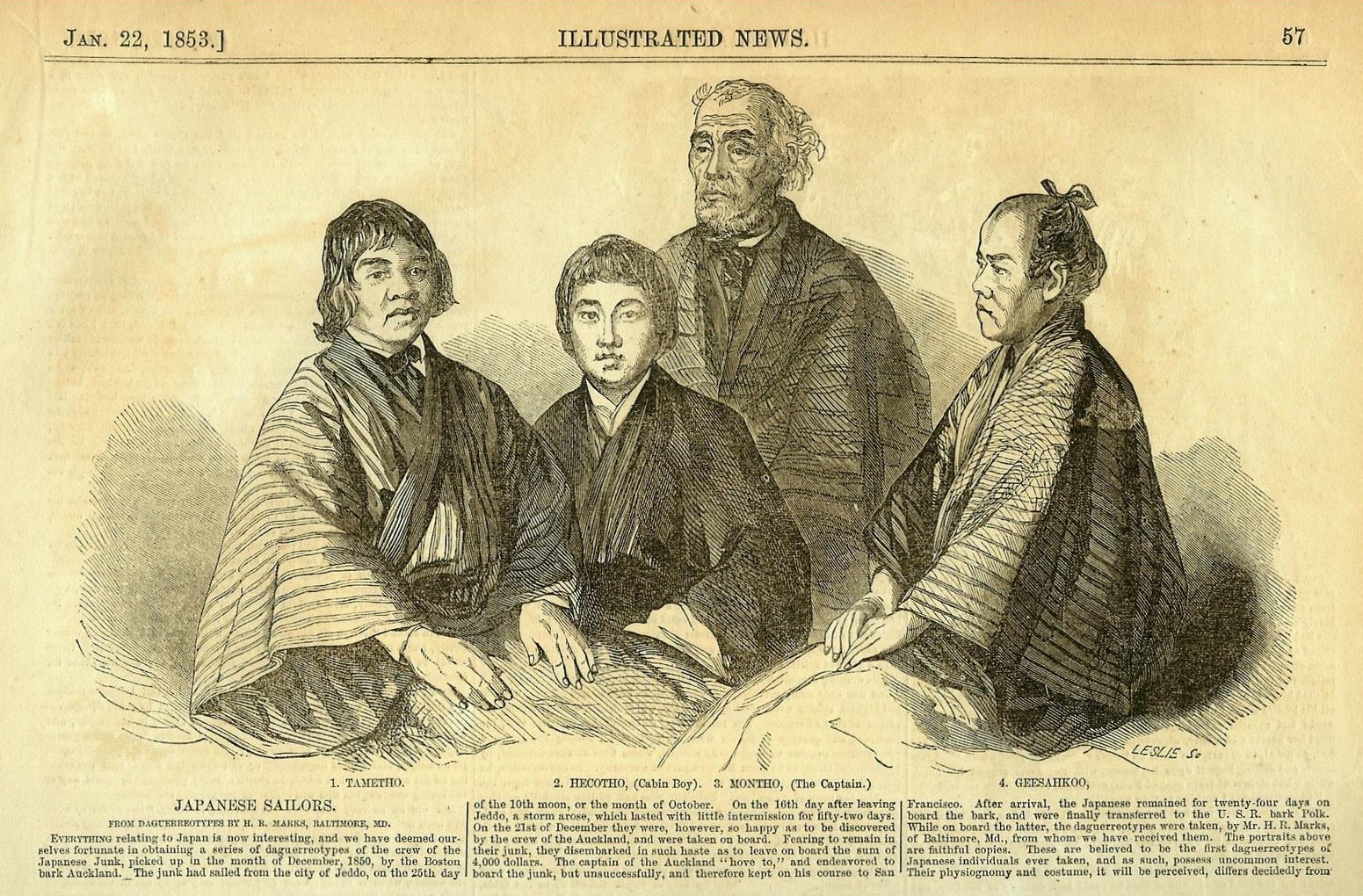

In 1850, when Japan still remained closed off from trade with the West, a Japanese junk vessel was shipwrecked in the Pacific Ocean, 500 miles off the coast of Japan. By luck, an American barge called the Auckland, carrying sugar and other goods, rescued the 17 men on board along with some of their cargo. Instead of returning the men to Japan, the barge continued on its way to San Francisco. When the ship landed, the Japanese crew gained instant celebrity as exotic specimens from a distant land. People flocked to gawk at the men, with their strange appearances and unusual dress. Showcased as “curiosities,” the sailors were invited to appear at a masquerade ball where, according to one newspaper, they “created a great deal of amusement, by their looks of wonder and unique appearance.” One part of this story, however, has largely been forgotten: During the twelve days of quarantine before the Japanese men had even set foot on shore, they would undergo a medical examination by a man named Dr. Benjamin Franklin Edwards, a gold rusher en route back to his home in Alton, Illinois. In compensation for his services, Edwards received a gift of “Japan peas” that had managed to survive the shipwreck. Edwards brought these soybeans back to Illinois and gave them to the owner of a local flour-mill. After planting and harvesting the seeds, the miller distributed his yields to farmers across the Midwest. A few soybean seeds, nearly lost in a shipwreck, thereby produced the first substantial American soybean harvests.

A few years later, in 1854, when Commodore Matthew Perry “opened” Japan to Western trade through “gunboat diplomacy”—a threatening display of military force—the expedition’s agriculturalist, Dr. James Morrow, also got his hands on some “Japan peas.” Morrow sent these soybeans to the United States Commissioner of Patents, which distributed them to farmers across the nation. Subsequently, it became difficult to distinguish the Auckland soybeans from those appropriated by the Perry expedition, the tokens of a sensationalized racial encounter from the yields of a military confiscation. Soybeans thus illuminate entangled histories of racism and imperialism—from the “discovery” of “Japan peas” through racial spectacle and military invasion to the approaching legal exclusion in the late nineteenth century of Asian immigrants who understood their true value.

With both Chinese and Japanese people banned from immigrating to the United States by 1924, soybeans would not be widely cultivated until the mid-twentieth century. Initially, many Americans were unsure of what to make of them, believing them inedible or at least unappetizing. One popular magazine in 1917 describes the stacks of tofu in Chinese grocery stores as “bilious pyramid[s] of yellow-green cakes of bean cheese.” Yet early Asian Americans continued to cherish soy foods, with Japanese Americans establishing the first tofu shops in the continental United States at around the turn of the century. By 1905, there were six such shops, all of them in California: two in Los Angeles and one each in San Francisco, Sacramento, Isleton, and San Jose, my hometown in what is now the heart of Northern California’s Silicon Valley.

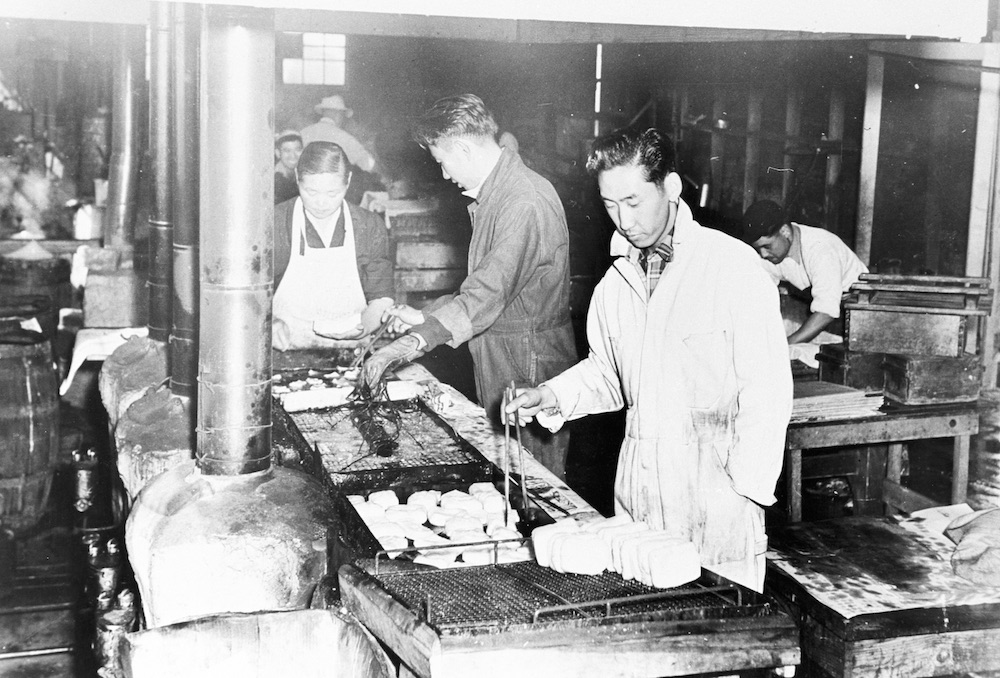

Making large batches of tofu is an arduous process, involving both physical strength and aesthetic sensitivity. In addition to lugging heavy buckets of soybeans and water into large barrels and vats, it necessitates a careful attunement to achieve just the right temperature and consistency. Traditional processes involved grinding soaked soybeans with granite millstones to produce a puree. This puree was then put through several stages of separation, boiling, and mixing before the resulting soy milk could be curdled and pressed into cakes. Today, high-quality tofu still uses a similar process. Unlike store-bought tofu, the product of these labors tastes fresh and creamy, its flavors surprisingly delicate.

The last family-owned tofu shop in the Silicon Valley, San Jose Tofu Co., sold handmade tofu just a block from my family’s apartment for over 70 years. I remember passing this small storefront with its blue awning on my walks down Jackson Street, the main thoroughfare of San Jose’s Japantown, on my trips to the local coffee shop. A man named Yoshizo Nozaki had opened the store in 1946. The year is not insignificant: he learned to manufacture tofu at the Tule Lake incarceration camp in California and started the business shortly after he was released. In 1942, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, forcing Japanese Americans in the Western United States to abandon their lives and livelihoods, the majority of the family-owned businesses that had made and sold soy products were required to shut down indefinitely. By the war’s end, many of these shuttered businesses could not easily resume operations. With their communities scattered and few resources at their disposal, the owners would have to start over from scratch.

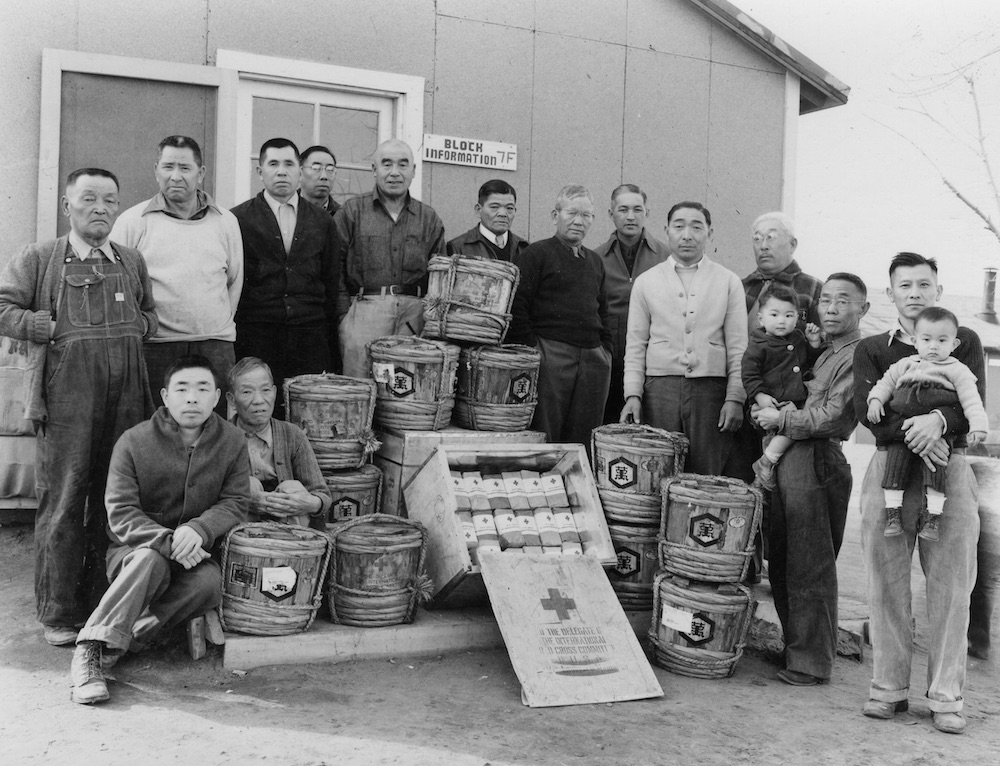

Yet, inside the incarceration camps, Japanese Americans quickly devised ways to acquire and manufacture tofu, miso, soy sauce, and other soy products to supplement their rations of inexpensive wartime foods: canned sausages, pickled vegetables, potatoes, breads, and other starches. For example, The Rohwer Outpost, a newspaper produced in the Rohwer incarceration camp in Arkansas, excitedly announced the opening of a “long-awaited tofu factory” in a front-page article published on October 23, 1943. Outfitted with a grinder and vats, this makeshift factory was able to produce 600 cubes of tofu a day to be distributed across the camp’s many blocks. The soybeans used at the Rohwer camp came from the nearby Jerome camp, where detainees planted and harvested the soybeans themselves. A man named Jujiro Yamaguchi, who had operated the Lafayette Tofu Co. in Stockton, California for 13 years before incarceration, oversaw the factory. Sixty years old by the time he left Rohwer, Yamaguchi would not return to his tofu shop. In the 1960s, the neighborhood where Lafayette Tofu Co. once stood—home to Stockton’s Japantown, Chinatown, and Little Manila—would be sliced apart by the Crosstown Freeway, and in 1999, an urban development project demolished what was left of this ethnic enclave despite the efforts of local Filipinx activists. Today, if you look for 119 E. Lafayette Street on Google Maps, you will find a 76 gas station and a McDonald’s.

Sifting through the archival materials on soy in the incarceration camps, it is difficult to differentiate government propaganda from the reality experienced by detainees. The War Relocation Authority (WRA), the government agency responsible for managing the forced removal and detention of over 110,000 innocent people, issued a series of photographs in 1945 depicting the tofu-making process at Tule Lake. The photographs reflect an eerie juxtaposition of anthropological interest and performative normalcy, suggesting both that “these people are different” and that “there is absolutely nothing unusual about their situation.” In one, a man oversees a grinder. The buckets of soybeans that he has finished processing are ticked off on a blackboard behind him in the Japanese style of tallying by fives. In another, detainees deep-fry tofu in an assembly line. A third photograph depicts a man examining soybean plants in a field at the Minidoka camp in Idaho. Long rows of the crop disappear into the flat horizon.

When I was about eleven, my mother bought me a copy of Farewell to Manzanar, Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston’s memoir of life in the incarceration camps, and I devoured it in a few sittings. At the same time, however, it felt like a history that was only obliquely our own. Although she has now lived in the United States for over 25 years, my mother has never identified as a Japanese American, but instead sees herself as a displaced Japanese person. Both physically and emotionally distanced from her Japanese family after marrying an American man against their wishes, my mother carried with her a sense of homesickness that we rarely discussed, a feeling of loss that often verged on regret. Consequently, for most of my life, I did not identify as Japanese American, either. I maintained a double identity: I was Japanese, and I was American, but never the two together. My family moved to the Silicon Valley along with an influx of first-generation Asian immigrants, many of whom came to the United States to work in the tech industries. At school, the Asian kids drew clear distinctions between the “fobs”—the “fresh-off-boat” Asians, an acronym we pronounced like the pocket watch—and the Asian Americans who were given no special designation at all. As only “half,” I lacked definition, floating somewhere outside that binary.

Having learned next to nothing about Japanese American incarceration in school, when I read Farewell to Manzanar I remember being, more than anything, fascinated by the discovery that the detainees engaged in activities like baton twirling. I had taken my concept of the horrors of World War Two from images of Auschwitz and Hiroshima, and at that age, I had little understanding of the devastating effects and dangerous implications of racialized mass incarceration. Still, I realize now that my mother and I made a choice, whether consciously or not, to dissociate ourselves from an identity linked to histories of discrimination, to histories that felt—even given ordinary comforts like baton twirling and tofu—abject.

When I decided I wanted to tell this story, I thought I might stop by San Jose Tofu Co. to talk to the owners. However, I never found the right moment, and on my last visit home, I was disappointed to discover that the store had abruptly gone out of business. Instead, I read a series of articles in the local papers explaining the reasons behind the closure. Nozaki’s grandson Chester, who inherited the business, had started to find the 40-pound buckets of soybeans too heavy to carry and could not keep up with soaring Silicon Valley prices. In a 2017 article in the San Jose Mercury News, Chester Nozaki reflects on his reluctance to explain the end of their family business to his 85-year-old father: “I just don’t have the heart to tell him… I’d feel I was letting him down.”

Down the street, in my family’s Japantown apartment complex, populated mainly by tech workers, boxes of pre-prepared meals from online delivery services line the long hallways each evening. Nearly every door has a box waiting in front of it; the effect is almost dystopian. I do not know how to make sense of this kind of loss, a loss only tangentially my own. Still, I vaguely remember a time when there were still cherry orchards in the Silicon Valley. Growing up, I always felt keenly aware that I was witnessing an unprecedented expansion, a paving over of the past. I experienced it as the compounding of a shiny but aching emptiness.

*

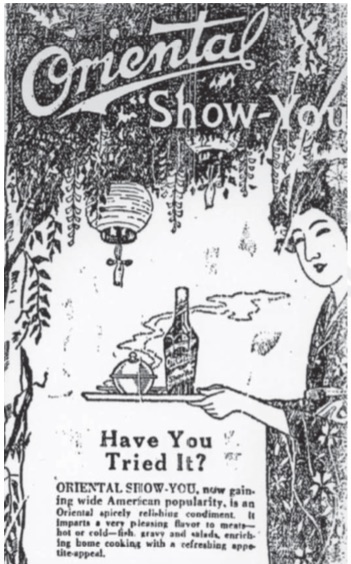

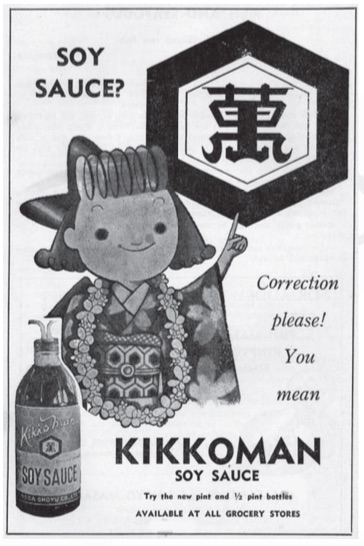

Not surprisingly, little of this history is evident in the information circulated by present-day American soybean companies and associations. After the war, in 1959, when my Hungarian grandfather wrote of his “extraordinary respect for a bean so little and innocent,” he was on the vanguard of mainstream America’s developing interest in soy. During this time, Kikkoman gradually shifted from marketing its soy sauce as a product for Asian dishes to presenting itself as an all-purpose, all-American seasoning. (The phrase “All-Purpose” still appears on a red banner across the top of Kikkoman’s label.) A 1956 advertisement announces that Kikkoman soy sauce will now be “available at all grocery stores.” The ad depicts a kimono-clad girl wearing a Hawaiian lei and drawn in the same plucky style as other American illustrations of the era.

In this way, while tofu would not be widely consumed for several more decades, soy sauce soon became a popular American seasoning. A Kikkoman cookbook from the 1970s shows a disembodied hand pouring Kikkoman over an all-American steak, and in 1973, the company opened a plant in Walworth, Wisconsin in what arguably became the first Japanese production facility on American soil. Kikkoman continues to nurture its Wisconsin ties: In 2007, the company donated over a million dollars to build the Kikkoman Laboratory of Microbial Fermentation on my campus at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. That same year, in a full-page color advertisement in the New York Times, Chairman Yuzaburo Mogi published a letter thanking the American public on the fiftieth anniversary of Kikkoman’s so-called “mainstream” presence in the United States. The letter states, “Over the last half century, you have embraced our soy sauce, teriyaki, and other authentic seasonings and products. You have made us a part of the American pantry.”

Today, many American soybean associations insist on the soybean’s “all-American” character by downplaying its Asian origins. The narratives they provide proudly proclaim that Benjamin Franklin owned some of the first American soybean seeds and that Henry Ford used soybean plastic to manufacture his cars. As legend has it, Ford spilled a bag of soybeans on the floor of his research facility and told his engineers, “You guys are supposed to be smart. You ought to be able to do something with them.” This is an archetypal story of American pragmatism, of capitalist spirit, one in which “something” is made out of “nothing.” But I often think the American story is actually the reverse: How many times have white Americans declared something “nothing” in order to justify taking something of value?

Then again, I started to write this essay not because I wanted to mourn soy’s appropriation, but because there is something about these historical fragments that enchants me. Soybeans can, of course, be eaten by anyone who wants to eat them. What I want to recognize is that, for some of us, a food is not something we can so easily cast aside before finding a new fad to follow. The Japanese American history of soy recalls this fact: One of the first issues of the Manzanar Free Press, the newspaper published at the Manzanar incarceration camp in California, mentions the procurement of 130 sacks of rice and 500 gallons of soy sauce. This is a seemingly mundane fact. Yet it also speaks to how mundane is the act of cultural and spiritual survival.

Alongside these larger histories, I have started piecing together my own past. Recently, an aunt on my father’s side came to Madison to give a talk at my university. A well-known feminist scholar, I watched her stride confidently before a packed auditorium, taking three questions at a time from the audience and answering them at rapid-fire speed. Although she had been close to my immediate family during my early childhood, I had not seen her for many years following a family dispute. The morning after the talk, I sat shyly before her as we spoke, not about academic matters, but about the childhood years when I had last seen her: “Your mother wasn’t happy here. I felt sorry for her.” Reflecting back on the conversation a few days later, I realized that this was something that I had always known, only not in so many words. I had understood it best through the language of food: My mother used to tell me of her memories of being forced to eat whale meat and powdered milk while growing up as a child under the American occupation, food supplied by a nation where she would later reside but which would never be home. It seems perverse to me sometimes that we need to eat to survive, when food should be so confused with our unspoken feelings.

During the soybean years, as I wait for the bus, I now think of the photograph of the man at the Minidoka camp, crouching down as he carefully tends to long rows of soybeans that stretch into the skyline. There appear to be some water towers in the distance, a slight dip in an otherwise flat and desolate landscape. I have seen similar scenes in the Japanese countryside: a few solitary figures set against a vast horizon, working diligently at a seemingly unmanageable task. These are images that I save away at the back of my mind. I wonder, too, if someday America might recognize them as a part of its agricultural and culinary imaginaries.