After the family saw this photo, ‘they couldn’t sleep.’

December 7, 2012

On Monday, Ki Suk Han left his Elmhurst apartment after fighting with his wife Serim. She tried to reach him by phone, but he wouldn’t pick up her calls.

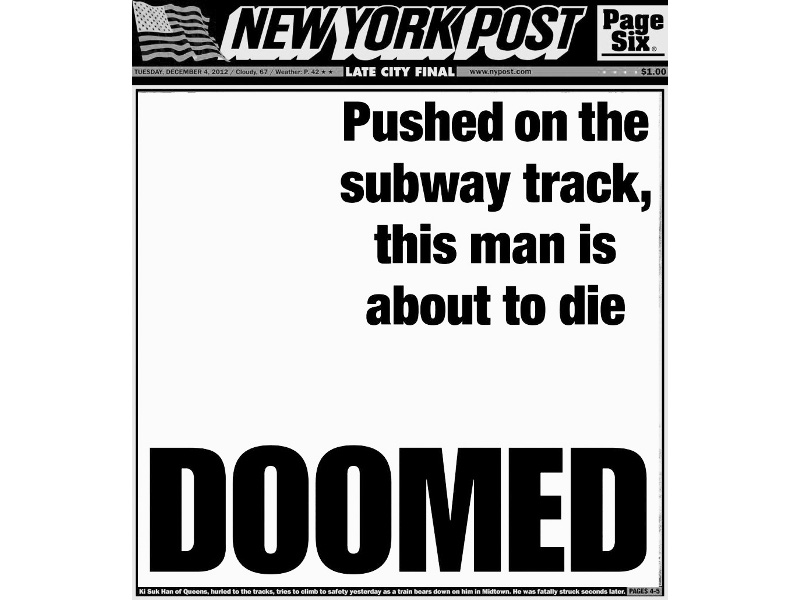

On Tuesday, he became immortalized in an image on the New York Post’s front page, clutching the edge of a subway platform with his head turned to face the Q train bearing down on him. The word “DOOMED” was printed over the bottom of the image.

As other outlets reposted the Post front page, the image of Han’s death multiplied. Speaking on behalf of Serim Han and Han’s daughter, Ashley, Reverend Won Tae Cho of Faith Presbyterian Church in Queens told a press conference, “After they saw this photo, they couldn’t sleep.”

Han was about the age of my father, who is also a Korean immigrant. How often do I see men like my father on the front page of an American newspaper? I cannot think of a single occasion. So why was this moment—at this threshold of certain annihilation, at the border between a man’s life and death—broadcast to the world?

To be sure, the photo and its placement on the Post’s front page have been the focus of a heated online debate. From the public space of the front page, one cannot really choose to look away. Condemnation of the photographer was swift to come from many quarters, including news anchors and journalists. Within this maelstrom of opinion, some nuanced debates about the ethics of photojournalism took place, with many asserting that photographer R. Umar Abbasi and anyone nearby had, first and foremost, the moral obligation to save Han’s life. Many do give the photographer the benefit of the doubt; without being a witness to the event, who could say whether Abbasi could have helped him? More indignation has been directed at the New York Post, as many question whether the photo should have been published at all.

But beyond professional ethics or the moral obligation of strangers to help each other, there is a dimension of this debate that has been not discussed as widely. The Post’s handling of the photo was not just an individual tragedy, confined to Han’s grieving family and loved ones. It was in many ways a re-enactment of the violence that befell him, a collective act of violence by a media outlet, testament to an industry that has long differentiated between the images of white bodies and brown bodies in pain. This differentiation isn’t harmless; it indicates a societal standard for those whose bodies we respect and revere, and those who can serve to illustrate, incite, and stereotype without regard for their wishes or the wishes of their community. After the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, numerous graphic images of dead Haitians proliferated in the media, horrendous scenes of uncovered limbs and ravaged bodies at makeshift morgues in the street and open air. When the catastrophic tsunami devastated Japan’s coastal communities, none of the dead were broadcast, and the focus of the photojournalism was on the survivors, working hard to cope.

We also have a decade’s worth of evidence to consider in the abundance and absence of certain images in the U.S. media. In the reams of photojournalism produced during the U.S. wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, there are few wounded or dead American soldiers, even when completely masked in flag-draped caskets. Embedded photographers who dared to publish photos of American soldiers killed in battle, even if the bodies were unidentifiable according to the military’s rules, were barred from all military units in Iraq. This is certainly censorship, but it is normalized by the reasoning that this policy offers the soldiers and their families some dignity amidst the terrible loss.

Yet the same media outlets have been allowed to broadcast the mutilated bodies and the raw grief of so many Afghan and Iraqi war victims and those in other conflict zones. Outstretched hands grasping for water. An amputee waiting grimly on a hospital bed. An inconsolable mother. A blood-spattered, orphaned child. These photographs have assailed us from the front pages and from television screens on a regular basis. Undoubtedly the intention behind many of these images was to lay bare the human costs of war and conflict. But did everyone react in the same way? Did we all weep together?

I suspect that in the stream of images of suffering people in the Middle East and other regions, contextualized as they were by text copy dotted with “militants” and “counterinsurgents,” it was not always easy to connect a smoldering ruin with the home of a human being, or the amputee to someone who was a father, a brother, a friend. For me, an image often needed the commentary of someone who could speak the language of the place in question, who understood its culture, its factions, its complex history, who could replace the numb horror of a grisly image with the immense magnitude of a life lost. In a New York Times article, journalist Anthony Shadid accompanied an Iraqi family in search of a missing man through a gauntlet of bureaucracy and gravesites in Iraq. By the end of the article, the story’s cover photo of a pile of wilted flowers strewn on a tombstone was incredibly weighted, and I wept. There was no need for a bloody image; there was, instead, a deep sense of loss.

Detractors might argue that the New York Post cannot be expected to hold anyone or anything sacred. It’s a tabloid, end of story. But the market, if that is what guides the newspaper’s editorial office, is still made up of people. In the case of News Corp, the media conglomerate that owns the Post, one need only look at the closing of its infamous British tabloid, News of the World. This paper, long vilified by politicians and celebrities for its shady and unethical investigative practices and protected by police collusion, was brought down in the end by widespread public outrage over its alleged hacking of a murdered child’s voicemail. Even the “market” has a breaking point.

The New York Post has always made a clear us-them distinction in its content, with a history of publishing derogatory, racist, and dehumanizing pieces about African Americans, Muslim Americans, Asians, women, and other groups.

They headlined Han’s death with this sensational copy: “Pushed on the subway track, this man is about to die.” There is something sinister, almost gleeful, in the wording; a buried note of triumph that they have captured this moment, a cartoonish framing of the danger Han faces. Where is the tenderness they show in eulogizing New York City’s police officers and firefighters who die in the line of duty? Perhaps the Post feels it is doing the world a favor by following up with its story of the suspect, Naeem Davis, and labeling him “FIEND” in its headlines. But why has it come to this tired storyline: a remorseless black man has pushed an Asian man to death? This is the narrative the Post specializes in producing; simplifying the misfortunes of others into a binary of villains and innocents. Nothing was learned by sharing Abbasi’s photo of Han on the front page. What the Post did was package up a life for a quick, sickening thrill.

While many reacted with anger to the use of this image, others commented that we are all becoming desensitized by the media’s use of sensational images. But again, we are not affected equally by the media’s choices. Many groups, including immigrants and people of color, suffer daily from the decisions made by mainstream media to criminalize and dehumanize them, by excluding them from the dialogue, by not considering them experts of their own lives and issues. Every media outlet, including the Post, has a choice when it comes to their content, and every reader has one as well, to respond when their media outlet abuses their power at the expense of a group or individual. And while the dialogue between corporate media and the ordinary reader has surely become a more lopsided one over the past few decades, it is not closed off completely.

Maybe the simplest way to put it is this. In regarding Ki Suk Han’s suffering, I felt pain for what had happened, which was intensified by the circumstances in which I learned of his death. No one’s death should be made into an easy spectacle.

The funeral for Ki Suk Han was held Thursday, December 6, in Flushing, New York.

A Korean American civic group based in DC, Council for Korean Americans, along with New York Seoul, an online portal for Korean American culture and politics, has called for people to write and tweet to the New York Post at @nypost and letters@nypost.com.