Poets write back to the literature of Partition on its 71st anniversary

August 14, 2018

Celebrated each year as Independence days for Pakistan and India, August 14 and 15 also mark the anniversary of the beginning of one of the bloodiest and largest mass migrations of people in history: Partition, when in 1947 the British colonial administration with support from the Indian Muslim league split the newly independent nation into West Pakistan and East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), with a Muslim-majority, and India, with a Hindu-majority and significant Sikh and Muslim communities.

Partition was horrifically violent: more than 15 million people became refugees displaced from their homes, hundreds of thousands of women kidnapped and raped, and over one million people killed. Since 1947, poets in South Asia and in the diaspora have wrestled with, memorialized, and lamented the legacy of the period in their writing.

Perhaps the most influential poem to come out of Partition and to memorialize this bloody chapter in history was by the atheist revolutionary Urdu poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz: “Subh-e-Azadi” (“Dawn of Independence”), which captures the failed dream of a postcolonial subcontinent amidst the wreckage of colonial violence:

This is not that Dawn for which, ravished with freedom,

we had set out in sheer longing,

so sure that somewhere in its desert the sky harbored

a final haven for the stars, and we would find it.

We’ve asked the following seven poets to reflect on the poetry of Partition. In poetry and prose they write back to Faiz, Aga Shahid Ali, Amrita Pritam, and the fractured history of the subcontinent.

1. Adeeba Talukder

2. Momina Mela

3. Zia Ather

4. Sreshtha Sen

5. Tanzila Ahmed

6. Faisal Mohyuddin

7. Fatimah Asghar

Adeeba Talukder

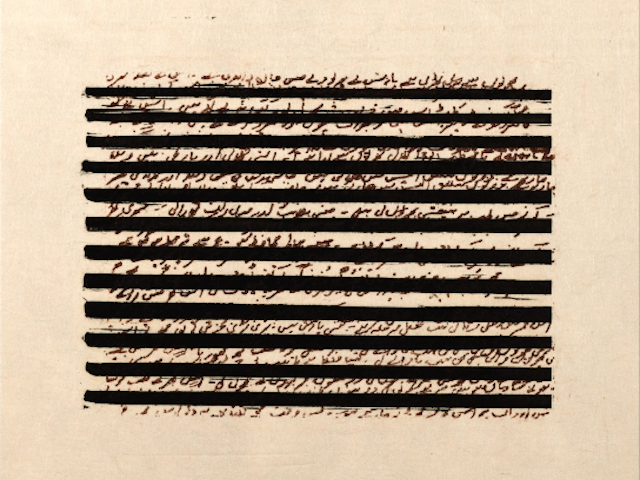

An ekphrastic poem after the Zarina: Dark Roads exhibit.

Dividing Line

You tore into our land

a crooked line.

That morning

we learned: the dawn

had been bitten by moths,

flying in droves, in madness

towards light. Unsure of the nature

of light, they had consumed

everything.

From above, we saw only

a silver abyss, one mile long,

either side plunged

in darkness—

the darkness of night, the darkness

of ash. We searched, sifting

the soil but found nothing.

We left, trying to preserve

at least memory. Our language,

like us, had no land.

~ ~

I say to a small boat

in black waters, alone

in infinity:

Whose pulse do you hold?

And what quivering

waters hold you?

Which direction

have you found forward?

What has lived in your past?

The wood darkens

with the night, until all

that is left is its silhouette.

There are no answers.

The air is empty, with nothing

to grasp.

In the distance, the horizon trembles

like a heartbeat.

~ ~

Tell them:

I have seen skin crushed

to a pulp, dead,

transparent as paper.

I have seen whole minds

turn to ash.

I have seen more water

than I understand,

seen humans claim

all light.

And some nights, I swear

it is so dark

even God cannot see us.

~ ~

This poem was originally commissioned by the Asian/Pacific/American Institute at NYU on the occasion of the closing of the exhibition Zarina: Dark Roads. Its title derives from one of Zarina Hashmi’s most famous works, Dividing Line

Momina Mela

Last October, I attended a mushaira which was held by the Hagop Kevorkian Center for Near Eastern Studies at NYU as part of their “Writing Partition in Urdu” conference. Prominent Urdu poets had been flown in from Pakistan, some of whom after a long day begrudgingly walked over to the podium and confessed that they did not, prior to the event, have a poem on the Partition but had written one especially for the event. And who could blame them? The Partition is not necessarily something that Pakistanis like to remember, let alone evoke through poetry—especially today with the threat of terrorism perpetually looming. I suppose this is why so many of the poems focused on just that: the struggle of reimagining the violence of anarchy. How do you encompass that in a poem? You don’t—instead, you rely on the poem’s failure to deliver the magnitude of loss.

Amrita Pritam’s famous lament, “Ajj Akhan Waris Shah Nu (Today I Ask Waris Shah)” implores Punjabi poet Waris Shah to rise from his grave and write on the bloodshed of the Partition:

Rise! O’ narrator of the grieving! Look at your Punjab,

Today, fields are lined with corpses, and blood fills the Chenab.

Although Pritam continues with references to corpses, cries, and bloody rivers, the heart wrenching feature of the poem relies on her assigning the responsibility of writing on these grievances to a deceased poet, more notably, Waris Shah, who famously authored Heer Ranjha, a tragic tale of two lovers. The lament is grounded in the act of turning away from a more private, excruciating lament. The inability to contain the loss was an underlying feature of the mushaira poets as well.

In Faiz’s “Subh-e-Azadi (Dawn of Freedom),” he is concerned with the mood of aftermath.

If this is still true then why is the

Heart still fervid,

Gall hot, eye votive—still

After the miracle?

The poem ends on a circuitous note: “Let’s keep going, friends/ We haven’t yet arrived,” and is more concerned with the social repercussions of the violence incited during Partition, especially how the new state of Pakistan will grow out of the bloodshed that accompanied the severing. Even so, there is not much for Faiz to meditate over, since much is left to uncertainty and so the call to “keep going” seems apt.

Writing poetry about large-scale violence, especially such where narratives conflict, families tear apart, and anarchy prevails is nothing short of traumatic. During the conference last year, I felt a great deal of sadness upon hearing Urdu and Punjabi poets attempt to say the unsayable. There is a generational lapse in the literature of Partition because the generation that experienced it first-hand are slowly passing on, and so all we are left with are their stories.

As a young South Asian poet, I haven’t quite figured out the best way to encroach the topic myself, but I sense it is a burden I carry, quietly weighing me down.

@momjeansmela | mominamela.wordpress.com

Zia Ather

This poem is a response to the tragedy of the Indo-Pak Partition that Agha Shahid Ali invokes in his poem “Learning Urdu” and also takes cue from another poem of his titled “A Pastoral,” that speaks to postcolonial violence wrecked on the Kashmiri people, their language, and sovereignty.

Kashmir only bleeds

in the district, near

what they insist is a border

the dust is still uneasy

on the graves, now only numbered

dead-men’s shirts

hang from the nearby trees

untired flags touched by

kids too young to know poetry

the gash across the verdant body

now even deeper, the glass map

of our country, broken still

i swear Shahid, i picked up where you left

in this long war of learning

our Kashmir only bleeds –

Sreshtha Sen

During my freshman year at Delhi University, I attended a pre-Pride event hosted by the then-newish Delhi University queer collective. I was still mostly closeted (I won’t be able to sufficiently summarize what the event was in response to, but I distinctly recall hiding behind a stone ledge from my professor because he’d just know) and it was the first queer gathering I had ever attended, the first openly queer anything I’d experienced. It was intimidating, slightly exhausting. So incredibly lonely. And yet, magical.

One of the speakers quoted a line from Agha Shahid Ali’s poem “Farewell.” I’d recently stumbled across Shahid’s work and later that year would have memorized several poems, listened to different renditions of everything I could get my hands on, and even attempted a few butchered translations of my own.

I’ve wanted to do that evening justice—that crowd, the speaker, Shahid’s own spirit, the music—but I’ve never come close to capturing what it meant to me. Shahid said, “If only somehow you could have been mine, what would not have been possible in the world?” and something shifted, in me and around me. Everywhere. That poem, or maybe that moment, or both, spoke to me. Labelling this queerness, my queerness for the first time—not as something hinged on past lovers or alien laws—but as need, as desperation, as friendship, but also as disappointment, and discomfort, as responsibility, history, memory, mourning.

For me, Shahid, Faiz, the history of Partition feeds into a collective South Asian queerness if there can ever be such a thing. The least interesting fact about my queerness is who I sleep with or whether the State will ever be on our side; queerness becomes so much more—solidarities broken and forged, accountability, caretaking, fragility.

Structurally too, I try to write as Shahid did—always addressing the beloved. The beloved in traditional ghazals stands for three figures at once: the lover, God, and the nation. When I write, whether it be ghazals or not, I try to be aware of all three in some form or another. God can become the poet or the listener (As Faiz Ahmed Faiz says in “Hum Dekhenge”: an-al-haq ka nara / jo main bhi hoon / aur tum bhi ho, I am God! Who I am too and so are you), the nation for so many of us becomes an amalgamation of unmappable homes, the lover becomes friends and family, the reader.

Saying or realizing that queerness becomes Partition and Partition becomes queerness does not negate the fact that there are people who have lived the Partition and will always remain closer to it than I am. As with most of history, there aren’t enough highlighted voices from 1947. Most of the dialogue and discourse we have heard are centered around Hindu India/Indians or Britain and around narratives that sound exactly like mine. I am ashamed to admit that I came upon W.H. Auden’s poem on Partition much before poets like Habib Jalib and Faiz. I’m thinking specifically about Kashmir, where borders and bleeding began long before 1947 and continue even now.

“Farewell,” said to have been written to Shahid’s Kashmiri Pandit friend after 1990, is not a poem about Partition or one that even mentions 1947 but it shows how the aftermath of Partition seeped into other lives and histories. Like Partition, in Kashmir “they make a desolation and call it peace.” Shahid writes, “In your absence, you polished me into the Enemy/ your history gets in the way of my memory” and I think of archives and folios we continue to build without questioning whose voices are highlighted. The consequences of carelessly partitioned states haunt every land today: Kashmir where bodies, borders, and bridges lie broken while, “In the lake, the arms of temples and mosques are locked in each other’s reflections.” As I write this, four hundred thousand people in Assam, predominantly Muslims, are being labelled illegal immigrants despite living here as if home, longer than I have. This was not the dawn they waited for. Chale Chalo ki woh manzil abhi nahi aayi. Come, let’s go, we have not yet reached our destination.

Tanzila Ahmed

Written after Langston Hughes’ “How Bout it, Dixie” in which Hughes connects the black freedom struggle in the United States to the anti-colonial freedom struggle in the subcontinent:

If you believe

In the Four Freedoms, too,

Then share ’em with me —

Don’t keep ’em all for you.Show me that you mean

Democracy, please —

Cause from Bombay to Georgia

I’m beat to my knees.You can’t lock up Gandhi,

Club Roland Hayes,

Then make fine speeches

About Freedom’s ways.

How About It… Now

The President’s Post Racial America

Appeals to me

I would like to see this fantastical myth

Come to be

If you believe

In “hope” and “change” too

Then share ‘em with me

Don’t keep ‘em all for you.

Show me that you mean

Democracy, please –

Cause from parking lots of Chapel Hill to streets of Ferguson,

Gurdwaras in Oak Creek to an AME church in Charleston,

From the hands of police in Baltimore to the hands of police in Alabama’s Madison,

I’m beat to my knees.

You can’t fund the Arab Spring and the Umbrella Revolution,

Shoot Mike Brown and Trayvon Martin,

Freddie Gray and Tamir Rice,

Ezell Ford and Rekia Boyd,

Then make fine speeches

About Freedom’s “Forward” Way.

Looks like by now

You ought to know

There’s no chance to beat Global Apartheid

By protecting the NEW Jim Crow.

Freedom’s not just

To be won Over There

It means Freedom at home, too

Now – right here.

Faisal Mohyuddin

In August 1947, responding to the immediate aftermath of Partition, Faiz Ahmed Faiz penned “Subh-e-Azadi” (“The Dawn of Freedom”), an Urdu poem that both acknowledges and bemoans the violence, chaos, and “false light” ravaging the newly independent subcontinent. The piece stands as a stark contrast to the romanticized view of Partition imparted to the young. Partition was, I was taught, not only necessary, but good, verging on holy. To question it, or to see it in the complicating, lamenting way Faiz does, was, as I write in my response poem below, “criminal, / an act of war”—an insult to the countless sacrifices made by those who fought for (and won) independence. And so, out of a reverence for my elders and forbearers, I complied outwardly with this sanitized, uplifting version of history. However, within the private corridors of my mind, I let my curiosity roam more freely toward truth, especially as I explored the scholarship around Partition and read with awe pieces like “Subh-e-Azadi” and the stories of Saadat Hasan Manto.

It’s no surprise that so many people denounced Faiz’s poem back in 1947 (too bleak, too fatalistic, too ungrateful), and why so many continue to malign it today, this despite the fact that its ending conveys an affirming sense of hope. Many of my poems investigate the uneasy relationship I and so many others have to Partition, poems such as “The Tomorrows,” “Partition, and Then,” and even “Ayodhya” in which the Hindu speaker, reminiscing about a long lost Muslim friend, blatantly calls Partition a “mistake.” “Obedience”—my response to Faiz’s “Subh-e-Azadi”—follows in the footsteps of these earlier poems; this time, though, I found myself, against my initial vision for the piece, leaning into to the sweetness and virtue of a sugar-coated past.

Obedience

As children, if ever we threatened to wake with questions

the ghosts asleep in the shadows of these adopted villages,

our elders pinched our ears, yanked our winced faces upward,

then, before a second whelp could leap from our lips, daggered

our eyes with theirs. Our ignorance of history, however innocent,

was to these otherwise sweet-tongued kin a failure, epic, criminal,

an act of war. The suddenness of their brutality so startled us

we would have ripped our tongues out to prove our shame, to broker

some truce, to ensure we couldn’t ever again give voice

to the doubts we held about Partition. It was clear we were never to toy

with the past, clear we’d never rise from sleep reborn

as birds. Who were we, they chided, to think we understood a damn thing

about the broken promises of this broken world still held

together by calloused hope? But then they retreated, made amends by

offering us a small tin brought in from elsewhere, nodding at us

to remove its golden lid. As their fingers force-fed us English

toffee which, it was true, did quell the sting at our temples,

they led us away, to Jinnah who watched over the house with

an ever-radiant sternness, his portrait garlanded with fresh flowers

every Friday morning. Without being told to, we climbed up

onto stools, took turns kissing his forehead, and descended

half a century earlier, or so it seemed, dizzy, punchdrunk on gardenia, hot

blossoms of pride blooming in our small, fragile throats.

Behind us, our beaming elders, rescued once again from the brink

of slaughter, fought back tears of relief, promised us mango

ice cream and toy guns that fired only imaginary bullets but

sounded deadly enough to ward off wild dogs, trespassers,

even poets. Behind them, emerging from the dark folds of moth-eaten curtains,

a small congress of ghosts now stood, weeping silently,

beckoning with mangled hands for a moment of refuge in the green hum

of our eyes. Every good sinner learns to become a cartographer,

to remake his own geography, partition off lush regions of shame

and heartache, render every remaining inch of land pure,

triumphant, as sacred and frail as the peace our elders forged from

the wreckages of empire. We’ll join their ranks soon enough, yes,

and with each round of toffee or secret buckshot of whiskey, our history

will taste sweeter, become a touch more perfect, no longer

a sanctuary for wandering ghosts, nor a place for the reckless

wonder of children yet to grasp the lasting worth

of obedience, who still dream of one day awakening as birds.

Fatimah Asghar

Partition

Ullu partitions the apartment in two—

a thin blue wall cutting the deserted hall

Toys & books on our side ,

refrigerator, sink & TV with our Auntie A.

She sends us rations throughout the day & we stay

separate, not allowed to cross. I’m 10

& haven’t been hugged in a long time.

Allah made a barrier between me & my mom.

Ullu makes a barrier between me & my aunt.

When he leaves we sit at the base of the blue wall

& I laugh loud so Auntie A knows

I’m alive & okay & she laughs loud so I know

she hasn’t left & we sit like this for hours, hands

pressed to the felt, laughing, laughing,

unable to see each other.

@asgharthegrouch | fatimahasghar.com

Excerpted from IF THEY COME FOR US by Fatimah Asghar. Copyright © 2018 by Fatimah Asghar. Excerpted by permission of One World, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.