In Richmond Hill, a neighborhood’s safety concerns are pitted against a city’s effort to bring youth offenders closer to home. And the residents are up in arms.

November 10, 2015

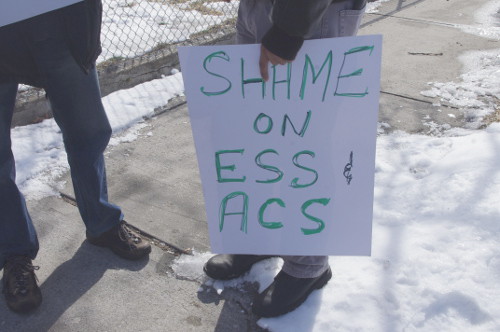

It was a sight uncommon on the tree-lined street in South Ozone Park, Queens. A group of about two dozen protesters marched down 128th Street towards 135th Avenue on an icy February morning shouting “Stop the prison!” There was a clear view of the bundled-up bodies from my parents’ bedroom window.

“Why are they protesting about a prison here?” my mom asked. Her attention was split between the television show she was watching and the goings-on outside.

South Ozone Park is an urban suburbia. The ice cream truck makes its rounds and kids ride up and down the streets on bikes in the summer. The peace is interrupted periodically by the Q37 bus rumbling down 135th Avenue. Often, the airplanes skimming the trees and rooftops in their descent to JFK airport are to blame for fleeting moments of incredible noise. Other times, it’s the bell from St. Anthony of Padua Church ringing at the top of some hour.

But of late the local tapestry of sounds has changed. The sounds of hammers and drills, as well as protestors, are common. The demonstrators that morning were not actually protesting a prison, but the proposed construction of a juvenile home for nonviolent youth offenders a block away on 133-23 127th Street. The brick building, a former church rectory, will house 18 juvenile offenders under the Close to Home program. Listed on the Department of Buildings, the construction and renovation of the building has racked up over 50 complaints from residents of the neighborhood.

“’I know these prisoners are humans just like us and need a second try,’ Desiree, a resident and mom, said. ‘But not in our community, where we have our kids playing and riding their bikes in the summertime. It’s important to give them a second chance, yes, but not here.’”

According to an article published on citylimits.org, New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg challenged Gov. Andrew Cuomo to create programs that help “bring city youth back down to New York City – and funnel moneys for their care out of state coffers and into city agencies.” Passed in 2012, Close to Home is trying to accomplish a simple thing: to lessen the distance between incarcerated youth and their families and communities.

But for the residents who were present at the rally, the initiative is too close to home, the distance not far enough.

“I know these prisoners are humans just like us and need a second try,” Desiree, a resident and mom, said. ““But not in our community, where we have our kids playing and riding their bikes in the summertime. It’s important to give them a second chance, yes, but not here.”

Her daughter, Stephanie chimed in. “I believe that some of these prisoners are probably not as hostile as we think. But we never know what they can do,” she said.

I don’t think it’s quite secure,” Desiree added.

The proposed home would be a “limited secure” facility and would feature a perimeter fence with lighting, gated windows, locked doors and surveillance cameras. “Limited secure” facilities still feature a restrictive and locked down setting, but are meant to provide juvenile offenders with an environment less like jail and more conducive to transitioning back into their communities. All services – educational, rehabilitative, as well as mental health services – will be provided on site.

“It is a massive transformation of the juvenile justice system–made possible by a statewide effort to reduce the number of young people in custody,” Chris McKniff, the press secretary for NYC’s Administration for Children’s Services, said in an email. ACS is the city agency responsible for administering the program.

New York City’s buildings have many lives. There is an entire classification system devoted to distinguishing the function of each. Curious about the building under construction on 127th street, I looked up its Department of Finance Building classification. It’s Class N9: a public building for “miscellaneous” asylums and homes. “Miscellaneous”, according to the Department of Buildings, covers asylum for everyone who is not a psychiatric patient, an orphan, a young person sentenced to juvenile detention, an indigent child, or a homeless person.

“The rally saw residents both old and new. It was a microcosm of the migrations which have changed the neighborhood over time. There were Sikhs present, Guyanese and Trinidadians, African Americans, as well as older Italian-American and Irish-American neighbors.”

“The prison was supposed to open on March 14th and we are in August now and it’s not open. We’ve managed to keep stalling them from opening and now it’s time to go to Albany and get some legislation passed so we can put the nail on this casket,” Mike Duvalle, resident and president of the Stop the Prison in South Ozone Park organization, told me at a rally in August.

Duvalle has a big personality. He is warm and does not need a microphone to carry his voice. He organizes with a fierce passion and urges members of the community to utilize their voice. When corresponding about an interview with him about the building on 127th Street, he urged me to come out and rally as well, especially since I lived next door to St. Anthony’s where they were organizing.

The rally saw residents both old and new. It was a microcosm of the migrations which have changed the neighborhood over time. There were Sikhs present, Guyanese and Trinidadians, African Americans, as well as older Italian-American and Irish-American neighbors. There were residents of South Ozone Park and residents who traveled from as far as Queens Village and even Long Island.

“I don’t think children need to see this in the area and they need to see more schools and something positive, not something negative, in the area. That’s the biggest thing for me, is just the image it brings to the community,” Victoria Dickerson, a resident of Long Island and rally supporter, said.

McKniff of ACS, however, defended the facility. “Close to Home emphasizes residential rehabilitative group homes in neighborhoods where young people are closer to their families and communities, thus allowing for them to transition into community-based aftercare services,” he said.

But the relocation of that rehabilitative work is a contested point among the residents I spoke to at the rally, as well as State Senator Leroy Comrie, who was present to congratulate residents for organizing and exercising their political power. He cited the Stop the Prison group as a model for residents in Queens Village who are fighting a similar proposal in their neighborhood.

“It’s not that we don’t want to take care of the people who are in trouble. But we want the city to respect us, consult with us, advise us, and involve us. They go to providers that have no real experience. We have plenty of smart people in the community, people that have worked for social service agencies, people that have worked with difficult populations – and they pick three providers that have all failed,” he said.

According to Comrie, Community Boards 12, 13, and 8 have the most shelter and mental health facilities anywhere in the borough.

The entire borough of Queens, however, only holds 23 percent of Class N9 buildings. The Bronx actually holds the largest percentage. Queens is home to one orphanage, and no juvenile detention houses or psychiatric treatment facilities.

“If you look around – and it’s not being mapped on the state and city level – we’re being oversaturated with various residents,” Assemblywoman Michele Titus said in a speech at the rally.

“If it’s not a group home, it’s a homeless shelter, and now it’s a juvenile detention center. We have our fair share. Our arms are wide open. We have the most homeless shelters here in Districts 10 and 12,” Titus added.

“Neighbors also expressed worries about their house values going down because of what they perceive to be a security risk. For others, the existence of the facility threatened the existence of the community itself.”

A similar facility for juvenile offenders already exists on 128th Street and is across the street from my house. Also a former church rectory, the center has been in existence since 2012 and serves six people on site. SCO Family of Services is the nonprofit that runs the residence. But many residents never even knew of its existence until recently. Not far is the Skyway Men’s Shelter. About 920 feet away from PS124 on 132-10 South Conduit Avenue, the shelter housed sex offenders and was another source of outrage for neighbors. It was announced in July that the Department of Homeless Services will remove sex offenders from the site.

Many of the demonstrators I talked to complained that Queens, specifically their neighborhood, was becoming increasingly saturated with facilities for the homeless, sex offenders and juvenile offenders. But, in fact, Queens holds only 21 homeless shelters. The only other borough with less is Staten Island, according to the Department of Homeless Services records.

“For limited secure placement sites, all services are provided on site, so the facilities must be able to accommodate those needs, including onsite education, health, mental health and recreational services,” McKnick said.

Young people in these facilities also have the opportunity to receive NYC Department of Education credits towards graduation, something that was not guaranteed for youth placed in upstate facilities, McKnick said. Of the 257 students who vied for high school credits, 61 percent earned 5 or more credits and 19 percent earned 10 or more credits, according to him.

A comprehensive study and evaluation written by Jeffrey A. Butts, Laura Negredo, and Evan Elkin of the Research and Evaluation Center at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in March of this year surmised that while the Close to Home initiative is not perfect, it is a transformative step in changing the way the juvenile justice system functions.

Close to Home, they said, reflects a broader trend where states are choosing to shift towards a model of community involvement and rehabilitation versus isolation in rural, upstate facilities. The John Jay study asserts that incarceration on its own does not improve the prospects of offenders once they are released, reduce the rate of re-incarceration or even aid public safety. But one is still left with a paradox of sorts.

Will tweaking the system to make it run smoothly actually reduce the number of incarcerated youth in New York City?

“First of all, jails are for profit, so once they build a jail the best way to keep money flowing into that jail is to lock up our children in this neighborhood,” a demonstrator told me during the rally. He has been living in the neighborhood with his wife and two sons for 19 years.

Both of his teenage sons have similar concerns, citing that the new home could be part of a pipeline that feeds the neighborhood kids into the prison system. “Our community is not perfect. If one kid goes to jail, there are gonna be 20 more. A lot of African American kids might be profiled. And I’m afraid I might be one of them,” he said.

“They need to build more schools, not jails,” his brother added.

“What does social rehabilitation look like in an immigrant neighborhood? Whose space is it? What responsibility do residents have to those members of our communities who are incarcerated?”

What do the images of barbed wires and surveillance cameras in one’s backyard do to a child of color?

Neighbors also expressed worries about their house values going down because of what they perceive to be a security risk. For others, the existence of the facility threatened the existence of the community itself. “This is our church and the parishioners don’t feel safe. We don’t mean to say they’re killers, but their mere existence is enough to make us scared. We don’t want our church and our community to become a ghost town because of the existence of a jailhouse,” Terry Martinez, a long-time resident of the neighborhood who migrated here from the Philippines, told me.

Many residents also expressed anxieties about possible breakdowns in the system that could threaten the security of the neighborhood. “If something breaks down, it can cause chaos here,” Daniel, a teenage resident, said.

There have been cases of youths going AWOL from program-sponsored facilities. Three teens left a group home in Brooklyn and were charged with raping and robbing a 33-year-old woman in June. Another Close to Home facility in Staten Island was shut down after the stabbing death of a teenager in July 2013.

The demonstrations began last winter and are still going. Residents continue to attend town hall meetings at St. Anthony’s, as well as community board meetings. With the help of Council Member Ruben Wills and the South Ozone Park Civic Association West, three residents filed a lawsuit to stop the construction. A group of Stop the Prison members traveled to Albany and met with Assemblywoman Titus over the summer.

In June, City Comptroller Scott Stringer denied a contract for the proposed facility. ACS, however, sent it back to Stringer on July 13. The contract was approved in August by Stringer, but according to an article in the Times Ledger, an “investigation will focus on ACS’s use of improper payment methods in the contracting and construction of the state’s ‘Close to Home’ juvenile group home sites across the city.”

Several things collided for me while writing this piece. The South Ozone Park rallies provided a local picture of a national issue. The Stop the Prison Organization offers an example of the value of grassroots organizing in our neighborhoods. But what, perhaps, does not sit as well with me is the rhetoric that permeates the Stop the Prison Organization’s rallies and the anxiety surrounding the shifting borders between public and private space.

What does social rehabilitation look like in an immigrant neighborhood? Whose space is it? What responsibility do residents have to those members of our communities who are incarcerated?

But most interesting to me about the rally were the silences, the things people were not saying – the perception of these kids as unwanted bodies, predicted problems.

It was not so long ago that immigrants were perceived in similar terms – as problems. Oscar Harding, the author of Uprooted and the son of Russian-Jewish immigrants, was the first person to challenge this perception and to study the immigrant as a subject rather than as a problem. The demonstrations, the fears, point to that pervasive anxiety which permeates urban areas: what do we do with unwanted bodies? Where do we send them? This is one instance of a larger question that transcends neighborhood politics.

From our backyard deck I can see the brick building with barred windows. Powerful and bright lights adorn its facade from all sides and a high fence topped with barbed wire surrounds it. In the middle of one of the many speeches made at the August rally, I looked up at the building filling in the background. A hand swung open the window bars and took a photo of the gathering with a cellphone. Aimed at the rally, the flash went off like a tiny moon. I could see it even in the blaring sun.