“To Hold Hands Again” and “When My Songs are Over, I Lose My Grip”

October 11, 2022

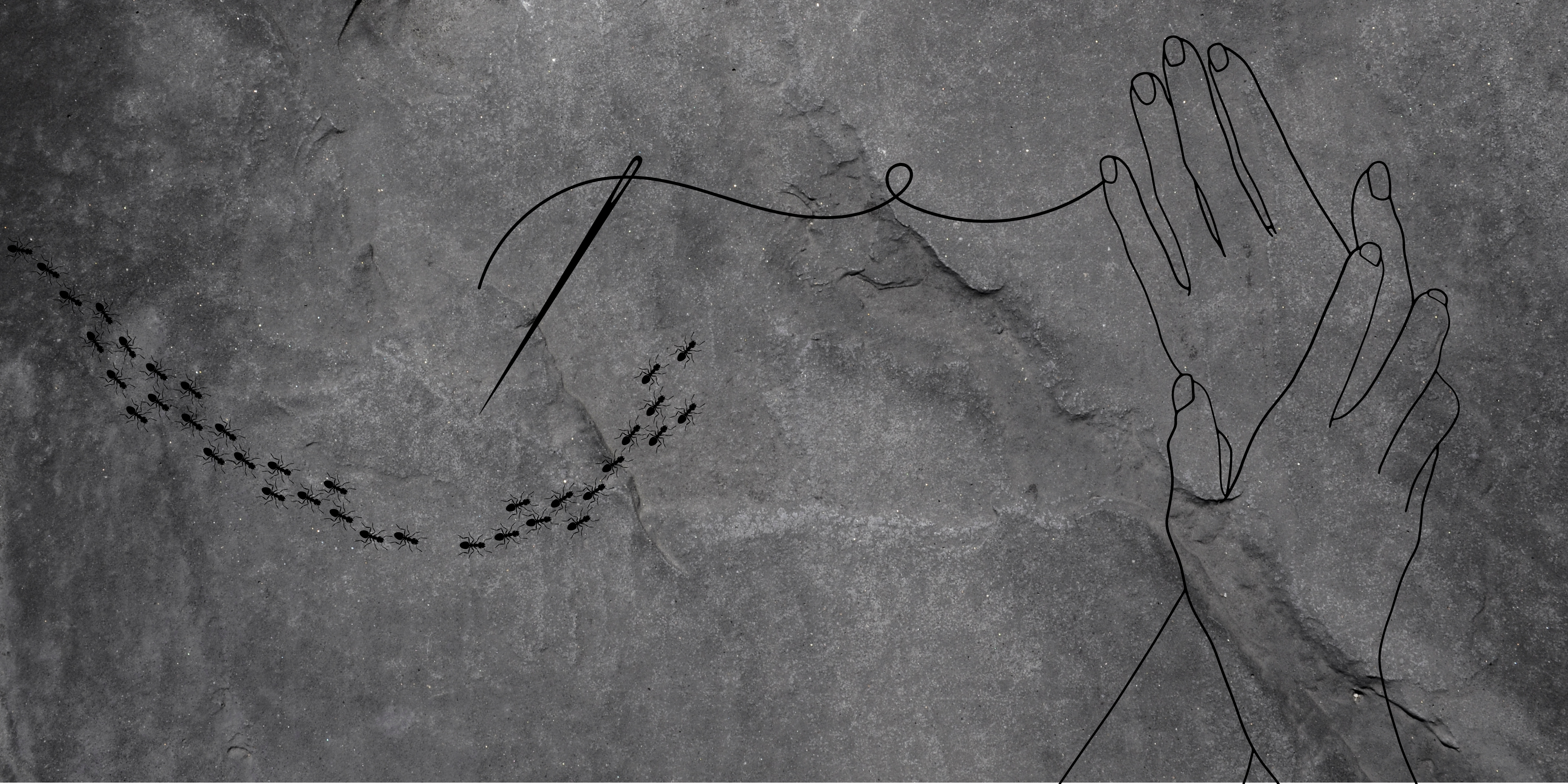

To Hold Hands Again

after “Dolores, Maybe,” by John Murrillo

My hand was rewoven once,

twice, the spring I fell into a sleep

that erased my memories. Coma,

they said, would not touch me. My disability

would walk again, small steps

up the road, before feeling dizzy,

before placing my prosthetic

on his hip so I could steady. This was

Oakland, California, 2010. No protest. I wouldn’t know

protection if it followed me.

I wanted to walk alone. His jacket

knew me when the breeze

bit me: I never took it off. I kissed him

on the cheek and said I’d return

with his menthols. Same same,

never thinking I wanted to cut

through Koreatown so we could

smell our favorite stews. Never

wishing I could loop my hand

to his belt buckle

and feel less lonely. My witness is a mirror,

curving back to when I clenched

the Marlboros in my palm,

a stone. My witness is brushing

my hair from my face; how,

in feeling, I heard the siren

before I stopped at his street. How I never saw him after that,

except when they carried him—his long limbs,

his soft hands, and the gunshot

wounds circling his chest.

I wanted to lie with him.

To pelt him with my stone hand,

to implore for his stay inside

instead of going out to find me,

because he feared I would not make it; I never

finished our walks, and never alone. In my 2010. Oakland, California.

My first love leaving before I could loop

my body again. I’ve never written

to anyone. Until now, until you. Please, I want

to remember his touch every time

my hand refuses to feel again.

Tethered to my prosthetic are fingertips,

strung like a razor wire, an ornament

that dances a path I wish I could hold on.

When My Songs Are Over, I Lose My Grip

How do you grieve when they’re gone

but not gone? How can I know when

I will die and let someone say my name?

That is what I plea to myself

after I run away from group home

the first time, to try my fate

on the streets—a humility, at best.

I latch my hands onto white bread,

bologna, and cookies, falling

for contraband like a chain-

in-progress, waiting to be caught.

Sometimes, a swish of vinegar

in abandoned houses; they never

took their cleaning supplies.

What I did to fight hunger,

to keep nothing God-like,

to be fine if I was ground

for prison. But it’d be my myth

if I didn’t keep living. Nobody

listened to an eleven year-old’s

song for freedom. Mostly,

I drummed towards an obsession:

give me a can of Campbell’s

soup, and, in the thick of my pitted

stomach, I learn my father’s

orphanhood. Mouth by mouth,

fallen like insects when I couldn’t

find food. I cupped the ants

and kneeled before what God

must have ordained on another

child’s neck: spell me a different

word for monster.