On the spaces we exist in and the legacies we leave behind

February 4, 2021

In the course of five years birthing my debut novel A World Between, I spent loads of time researching and going deep on various aspects of my characters’ identities. Being the good former Library and Information science student that I am, I spent countless hours in the vortex of my own internet searches, on the hunt for primary sources beyond Wikipedia, my eyes bleary in the dark while my wife slumbered at my side. Eleanor, one half of our team of protagonists, is a queer Japanese American woman whose family lived through incarceration during World War II. While I too am queer and Japanese American, my father was born and raised in Japan and moved here in the 1980s, avoiding the overt racism of earlier decades. I shaped Eleanor’s family’s experience and her inherited trauma through reading first-hand accounts of incarceration experiences and poring over photographs of Japanese Americans dressed for travel in fedoras and bobby socks, with only the belongings they could carry—a suitcase, a duffel bag—and a tag tied to their coat that identified them by name, identification number, and to which incarceration site they were headed. Kids in black-and-white photos who looked like me as a child, with blunt black bangs cut straight across the forehead. As I selected which incarceration camp would be the one where Eleanor’s family had been sent to, I noticed that many sites had not been preserved. All bear at least a stone marker, others have turned into makeshift museums where visitors can learn about what confinement was like for those incarcerated, and other sites have gone fallow—visual evidence of our nation’s preference for forgetting.

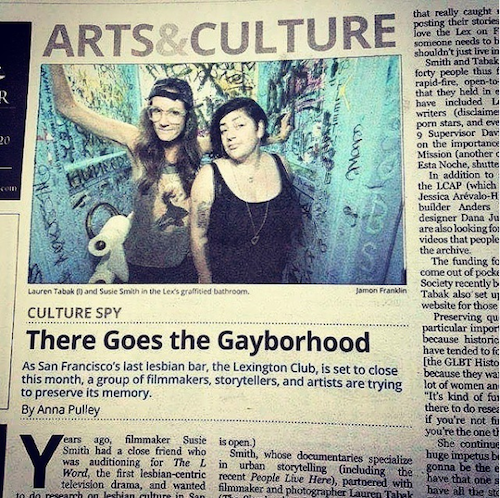

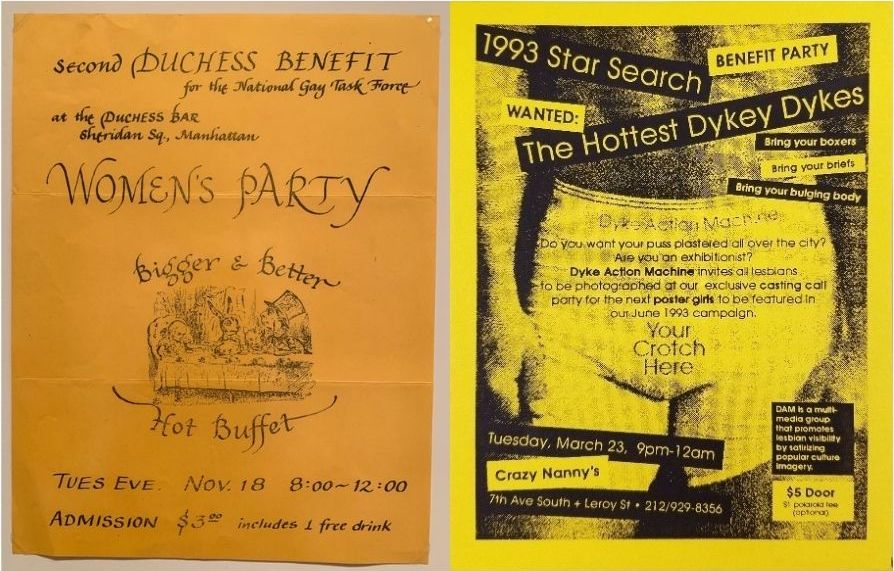

As a queer woman in her twenties, Eleanor frequents queer women’s bars and clubs. I dug in here, looking for the places I imagined she would have frequented in San Francisco in 2010, and learned for the first time about The Lexington, what was once a smashing place to meet, and probably more than meet, other queer women. The Lexington closed in 2015, the same year I began writing my novel, so I had to recreate the club from photos, videos, and articles documenting its swan song. A goodbye to a lauded queer women’s space is nothing new: while at one point there were once about 200 lesbian bars in the United States, now that number is a gutted 15.

Living with Eleanor for five years prompted me to meditate on the spaces we exist in and the legacies we leave behind. While writing, I connected the dots across these odd bedfellows––the site of former Japanese American incarceration camps, queer women’s bars, and clubs––and their erasure. So, bear with me, and here we go.

“Human failing”

I’m basically a socialist, so I had been taught that FDR was my guy. The government should help people. The government should solve shitty capitalist problems and try to improve people’s lives for the better. Where he falls all the way out of my esteem is in signing Executive Order 9066, signed on February 19, 1942. The order sent more than 100,000 Japanese Americans, two-thirds of whom were American citizens, into incarceration camps, under a rampant government and country-wide fear of Japanese people in the post-Pearl Harbor bombing haze that enveloped the nation. Over the course of five months, thousands of people were rounded up and sent to other parts of the country totally unknown to them: Arizona, Colorado, Wyoming, Idaho, Utah, remote parts of California. Blistering, punishing cold, and whistling, extreme desert winds, with slapdash construction that facilitated overcrowding. Though there were many places where Japanese Americans were incarcerated, there were ten main “relocation centers.” In my book, the Suzuki family was incarcerated at the Poston War Relocation Center, on the Colorado River Indian Reservation; the Tribal Council objected to their land being used in this way.

In the path of my research, I’ve mused on what my life would be like if I were alive in 1941. Though I’d escape the mass incarceration of my West coast brothers and sisters, us Japanese folks living on the East coast wouldn’t escape scrutiny. Many Japanese Americans were incarcerated at Ellis Island, those doors of America that I toured as a schoolchild, without an understanding of what my arrival on that island in another time would have meant.

In this thought experiment I also consider my parents’ biracial marriage, and the impact on my life if we had lived on the West Coast. A fascinating doctoral dissertation on the subject of “mixed marriages” of this time sits heavy: as my father is Japanese, our home would have been considered a “Japanese environment,” and therefore our early dismissal from incarceration would not have been likely. Or, maybe mine would have, with my 50 percent white blood, but he would have to stay. Later on, we both could go, but not back to a West Coast home. And my mother: the choice to go with us or stay in the first place would’ve been her difficult decision to bear.

As disgusted and ashamed as I am by this and so many other chapters of American history, I take note of another odd, curling shoot of this story: people made do; shikata ga nai. It can’t be helped. People lived, despite inhuman living conditions and sorely inadequate medical care. Incarceration camps were places for some version of the community Japanese Americans had in their West coast towns and cities. People met and fell in love. They played baseball. They taught and attended art classes, exhibiting their work. They wrote critical newspaper articles for camp publications and protested against unfair arrests.

I go around trying to make everything queer. As I considered life in an incarceration camp, my mind—of course, as always—wondered what it was like for queer Japanese Americans. Being stripped of one’s civil liberties doesn’t make for a fertile place to meet and be in community with other queers. What history has kept for us is a handful of half-stories and nothing about queer Japanese American women, so this may be lost to time—and heterosexism.

“I’ve other work I want to get done”

When my wife and I moved to Brooklyn, we decided it was time to make new friends nearby, and in an effort to do this we ventured out of our comfort zone to attend a Lesbians Who Tech meetup (context: we normally spend all of our time together, just the two of us; my day job is in nonprofit tech). The event was held at The Dalloway, a now-closed “lesbian-leaning” bar and restaurant named for Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway. Downstairs in the bar/lounge, I tried to make conversation and connect, but no one really fit until someone spilled a beer on me and insisted they buy me a drink. Suddenly that delightful friend meet-cute spiraled into meeting other women at the event, and for a spell in our new New York life we hung with a group of queer women, grabbing brunch and going to whiskey tastings and dancing at Henrietta Hudson’s after the Dyke March, surrounded for the first time by a circle of queer women friends. Building and relishing in community; like The L Word, but without the drama. This is the power of queer women’s spaces, that bring you together with people like you, to meet and dance and homosocialize. As I wrote about Eleanor, I inserted scenes of her in queer spaces, some specifically for women, knowing this would be an important setting in which to see her live her life, dancing and flirting and comfortable in her own skin.

These spaces for me have been safe and fun places to be with friends, but of course, their history is much darker: these dedicated bars and clubs exist because we were/are not welcome elsewhere, with threats of civilian violence, police action, or homophobic or transphobic laws. I’m lucky in terms of age, geography, and gender identity and expression that I don’t have to seek refuge in these places—except for that one time at a bar in Krakow, Poland, where I think we knocked on an unmarked door, but even then that was a choice. The history of queer women’s bars and clubs, and that of any queer people’s spaces, is born of violent exclusion from seemingly mainstream heteronormative settings. What blooms from that exclusion are spaces that transmit a rebuttal to heteronormativity, a resistance against what women are expected to be and on whom they are supposed to focus (read: men). To be amongst other queer women promotes safety and belonging, especially in circumstances when queerness can feel isolating depending on where you live and who you know. Preserving these spaces is about ensuring that the next generation can also get beer spilled on them and make lifelong friends, but more than that it’s about taking a deep, comfortable breath in a world rigidly fashioned for others.

“A place where our ancestors legacy will be told by future generations”

Preserving incarceration spaces is a plea—to the present, from history—to remember the worst in us, so that we learn from our grave errors. In 2012, an exhibit of self-portraits taken by Muslims was on display at the Heart Mountain Interpretive Learning Center, a former site of Japanese American incarceration. Its aim was, according to the executive director in an interview with The Margins at the time, “to stimulate thinking and conversation around America post-9/11 and how people might be stereotyping people of Muslim faith in the same way that Japanese Americans were stereotyped in 1942.” This exhibit could have been displayed by any organization or gallery, but there is power in the connection between communities because together we are more powerful against the forces that want to oppress us. There is poignancy in an exhibit like this, on land that was once the site of incarceration, centering people who are the survivors of the same racist poison.

All ten of the “relocation centers” built during Japanese American incarceration have monuments, and a few have museums. In many cases the original buildings do not stand; at the site of the former Poston War Relocation Center, the Colorado River Indian Tribes use some of the buildings as utility spaces. In the other places, save for that monument, what happened is all but forgotten. Rusting tractors dot the land. Watchtower remains lay in a ditch. Natural vegetation has taken over. It is far from an ideal way to mark something of tremendous national importance.

In my research, I learned something that surprised me: many Japanese American survivors and their families participate in pilgrimages to visit these sites. To me, literally revisiting the place of such pain sounds like a dreadful masochistic exercise full of foreboding. And yet, one of the first pilgrimages to Manzanar in 1969, another site of incarceration, was held, according to the Manzanar Committee, “to start filling in the blank pages in their history books—left blank because their parents and grandparents were so reticent to speak of their incarceration, still suffering from the pain and strong feelings of guilt and shame attached to this experience so many years later.” Place and location mattered to these descendants; it was where their experiential learning could begin, absent the stories of their elders. They could look at the same horizon that their grandparents saw. Their feet pressed into the same earth. Preserving these spaces of pain and memory maintain, as Japanese American Memorial Pilgrimages proclaim on their website, a “place where our ancestors’ legacy will be told by future generations.”

“I Really Care, Don’t U?”

The aforementioned Lexington, affectionately called The Lex, is now the site of a cocktail bar charging $24 per drink. These unfortunate turns for queer bars and spaces—the quintessential It’s-Now-A-Starbucks kind of thing—are very real. In the book, I reference a party called Meow Mix, repurposed from what it was: a bar in New York that I tried to attend to celebrate my twenty-second birthday but couldn’t because it had unexpectedly closed. According to A Spacial History of Lesbian Bars in New York City by Gwendolyn Stegall, the owner of Meow Mix Brooke Webster blamed the closing in part on “neighborhood demographics.” Stegall puts a fine point on it: “The changing ‘neighborhood demographics’ was code here for gentrification.” My former neighborhood, Park Slope, used to be so populated with queer women that it earned the moniker “Dyke Slope,” a label that is no longer appropriate in a place that is only affordable for Spotify employees; the dykes have had to move elsewhere (this dyke included). Bars likewise get affected by skyrocketing rent, and if the queer women who once lived there can no longer afford to live there, and the neighborhood is mostly upper middle-class straight people not interested in a queer bar, well, that space may not be well-positioned for the long haul. And with COVID-19 ravaging every facet of American life, especially spaces where people congregate inside in close quarters, I’m not sure queer bars and clubs can make it through the winter.

As affectionate as I feel towards my local queer women’s bar, Ginger’s, parenting doesn’t make it easy to take the family down to get a drink. For a place that has fostered community in my life, where the hell is my loyalty and support? It’s there that I pause to ask this question: who cares? (I do, deeply, hence this article, but that’s beside the point.) Who cares if the structures that were once incarceration camps disappear entirely or if there are no more queer women’s bars and clubs? There are history books and apps. Musicals featuring George Takei and an L Word reboot. We’re all set, right?

But we’re not all set. Place makes the experience of learning and understanding come to life. At an annual cleanup on the site of the Gila River War Relocation Center, an Arizona State University student reflected, “As… a young millennial who’s white… I want to learn as much as I can… I think there’s a lot of white people that want to do the right thing, but we need to learn and be a little embarrassed and figure out the truth of things… You can research anything you want on the Internet nowadays, but actually having to walk out here and realize that this was the weather that people woke up to—and stepping on the ground and seeing what people had to experience, is just always going to be completely different.” Another volunteer at the cleanup, one with family ties to the incarceration site, spoke like a poet: “Just looking at it hits the heart.”

The National Trust for Historic Preservation asserts that “America’s historic sites are irreplaceable… physical reminders of the diversity of our experiences and the history we share. They can celebrate our triumphs. Or challenge us to confront the harsh realities of our past.” And on saving older structures, they have a brutal reminder: “There is no chance to renovate or to save a historic site once it’s gone. And we can never be certain what will be valued in the future. This reality brings to light the importance of locating and saving buildings of historic significance—because once a piece of history is destroyed, it is lost forever.” When at our best, we seek to understand ourselves in relation to others, and why the world functions as it does. Maybe it’s my pandemic frenzy, desperate for public life once again, but I believe this knowledge can be best understood in person: on a dance floor, lingering near a dark wood bar, or in the solemn dust of a barren desert where people with faces like my father’s tried to get through the day.

“The story of places is the story of all of us”

As our country literally and figuratively burns, scarred by the myriad mistakes of our past, I can only offer remedies that aim to walk us into a better, more just future. One of my aims when this pandemic eases, whenever that might be, is to begin visiting sites of Japanese American incarceration. I’ll also keep an eye on the Japanese American Confinement Education Act, introduced in October 2020 by Representative Doris Matsui—born into incarceration, at the Poston War Relocation Center—which seeks to permanently reauthorize a sixteen-year grant program that funded the preservation and interpretation of incarceration sites. You can also donate to nonprofits that help tell the stories of these sites, a list of which can be found here.

Turning the page, considering for a second our sweet sixteen queer women’s bars that are left: fund your local bar or one that breeds nostalgia in your heart. For me, that’s a donation to my local’s GoFundMe. We can pay tribute to our fallen queer women’s bars and clubs through the Addresses Project, or by going to a bar takeover where we can have the experience of community if not the fixed location that would be more desirable; in lieu of many more bars and clubs opening up, that might be our best bet for community and dancing.

While working on my next book, I connected with someone who, when I described Eleanor’s family in A World Between, kept shaking her head because I was essentially describing her family’s life before, during, and after incarceration. It was eerie and probably about the collective unconscious, but because I’m from New Jersey I did some mental fist-pumping over that. When I think of these spaces that I’ve spent so many hours knitting together in my mind, a win in depicting the incarceration experience feels like winning the lottery. Because of my background, I have a closer relationship to queer women’s spaces, frequenting them as I did in my pre-parenthood days to drink too much and be with queer women friends.

My thoughts, as they often do, drift to Eleanor. For her, there is no “closer” or “not closer.” She is queer and she is sansei, identities on equal footing. The trauma she inherited from her family made its way into her DNA along with her queerness. I depicted her in queer women’s bars from coast to coast, but I never brought her the idea of a pilgrimage, to visit Poston as a way to learn and reclaim. The dedicated, motivated, and righteous person that she is, I can see her traveling with her family to take in those bright blue skies and palm trees, in community with other Japanese Americans. She’ll think of her grandmother and those they’ve lost, squinting in the sunlight to imagine her family’s barracks. Her thoughts will drift to other people now far more vulnerable than Japanese Americans, and she’ll think about how she can be most useful, and she’ll bring her whole self into whatever inevitably comes next.