While America’s most storied hospital welcomes survivors, your body protests: what did it survive?

November 14, 2017

The nightmares begin within days after the terrorist attack carried out by Al-Qaeda’s affiliates.

The sequences in your nightmare carry through the summer. Pools of blood dripping down a staircase in an upscale apartment, a conversation between you and a prominent human rights activist in the diplomatic enclaves of your home country’s capital.

In your nightmare, he tells you that he is scared of the burglars who broke into his house, who sawed away at his guest room’s wrought iron balcony grills one night. He was so scared, he was unable to sleep for three nights after. After you commiserate, you excuse yourself to use the restroom. Upon return, you find his body hacked. What was once nose and eyes and hair is a spilled scalp, a pool of blood filled with unrecognizable and bloated skin.

You wake up screaming, drenched in sweat, remembering the men who had murdered your friend. Of the burglary – unconnected – that he had faced months earlier. It’s just you and your insomnia at moments like this, when these two fragmented scenes that your subconscious has connected returns, night after night.

You’re in New York City now. Looking back will not help you move forward.

You want a night of unbroken sleep. Moreover, you want to make sure you are able to veer your memories of your friend’s life away from the prism of his death, of remembering him for his achievements. You want to find a way from disconnecting from the meaninglessness of his untimely murder.

You want to remember the bamboo groves you sat under as you celebrated spring, serenaded by wasps of jasmine flowers wafting through his balcony, petting his Persian cat before performances of concerted satires about the country’s political scene in his living room, where you regularly gathered for classical music, satirical plays, parties, cups of tea, and warm welcomes.

You want all these, but your mind remembers watching video footage that was forwarded to you, of his body being dragged across the floor by onlookers after the murder, destroying forensic evidence. Nearly two years after his death, the murder case has progressed with little justice. The murderers escaped unscathed.

You’re in New York City now. Looking back at these failures does not help you move forward with conversations.

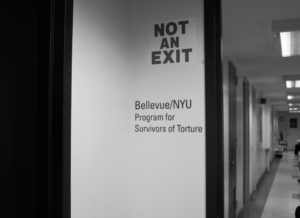

Some phone calls later, a director at a local NGO points you in the direction of Bellevue Hospital in Manhattan. In 1995, psychiatrist Dr. Allen Keller founded the Survivors of Torture program, in partnership with NYU’s School of Dentistry. Noticing the lack of mental healthcare facilities available to survivors of the Pol Pot regime in Cambodia, Dr. Keller decided to redress the situation for asylum seekers in New York, bringing mental health into the equation of holistic health care for those who have immigrated to the United States from conflict or post-conflict contexts.

The Survivors of Torture (SOT) clinic at Bellevue primarily serves political asylum seekers and refugees. It is an innovative measure meant to provide trauma healthcare for its patients. Since its inception, SOT has provided free healthcare to over 4,000 political asylum seekers and new immigrants from 100 countries. Much of Bellevue’s SOT funding comes from private donors. At the SOT clinic, you can receive sliding pay scale group therapy, family therapy, help addressing individual mental health issues, legal services, and housing services. For asylum seekers who are forced by the Federal government not to work for their first few months living in the United States, the SOT clinic is healthcare manna, even while you wonder what it is exactly that you survived.

Despite the rationalities you tell yourself by day, at night you wake up screaming, drenched in sweat, remembering the extremists who had

murdered your friend. Then you remember the burglary – unconnected – that he had faced months before he died. It’s just you and your insomnia at moments when these two fragmented scenes return, that your subconscious has connected.

Bellevue was founded as an infirmary in 1738 for incarcerated New Yorkers.

Among NYC hospitals, Bellevue’s instrumentality as an institution long serving America’s most recent immigrants is undisputed. Its nearly 300-year history has shaped it into an integral center in New York’s medical landscape. It provided the city’s first civilian ambulance, the first nursing school for women, the first departments of psychiatry, medical photography, pediatrics, and even NYC’s first outpatient clinic. Its medical staff have developed life-saving vaccines, won Nobel prizes, and treated diseases that reflect epidemic maladies of the day. If it has passed through New York, whether it is yellow fever or HIV or Zika; it has passed through Bellevue.

“Nightmares are common after being subjected to a terror attack. It’s your body protesting what it’s been exposed to.”

While global leaders and homeless patients are treated equally by the hospital’s emergency service centers, its place as a medical mecca is grounded as a hospital for immigrants, David Oshinsky writes in “Bellevue: Three Centuries of Medicine and Mayhem In America’s Most Storied Hospital.”

As luring and appalling as it is for its roots, Oshinsky’s accounts detail how beguiling one of America’s oldest hospitals is. Bellevue once housed John Lennon’s body in the morgue at the same time as his killer Mark David Chapman was being questioned by the chief of the hospital’s psychiatry department. At another point, a rat infestation saw a woman’s dead newborn being consumed by rodents. Norman Mailer was admitted here after he killed his wife in a drunken brawl; O. Henry, the prolific short story writer, arrived with cirrhosis of the liver. Lead Belly, the blues singer who wrote “Bellevue Hospital Blues,” about his fears of not walking again after illness, died here.

Perhaps the most infamous accounts of Bellevue’s history, that

oftentimes overshadows Bellevue’s constant achievements as a medical haven par excellence, is the lurid details from Nellie Bly’s, “Ten Days in a Mad-house” that has given it the flair of a bedlam, and William Randolph Heart and Joseph Pulitzer’s lurid exposes have over time, influenced obfuscations of the hospital’s reputability.

Many of Bellevue’s “survivors,” as the aid workers often refer to those who are seeking political asylum in New York City, come from Francophone Africa and repressive regimes in Asia and Latin America. Francophone Africa provides 44 percent of Bellevue’s SOT patients.

“Nightmares are common after being subjected to a terror attack. It’s your body protesting what it’s been exposed to,” you are told over the phone by one of the leading psychiatrists in the program.

“It’s normal,” she insists. “Come in and we’ll talk more about this.”

The psychiatrist and you have a candid discussion about how despite being around for over two decades, patients normally discover the clinic through word of mouth. A family can come from a country like Sierra Leone, and hear about it from another family who are patients here. They can apply directly, if they should want to, or they can be recommended through local NGOs, such as Amnesty International, Freedom House, Pen America, the International Women’s Media Foundation, or the Committee to Protect Journalists.

You first enter the hospital on a cold day in October 2016. A television in front of the hospital’s gift shop loops the message: “We care about their health, not their immigration status. We respect the privacy of all patients, regardless of immigration status. All New Yorkers should seek care without fear.”

Another sign, near Au Bon Pain, flashes “welcome” in Urdu, Hindi, Bengali, Arabic, French, Hungarian, and Spanish, among 30 other languages. You pass a woman in a black burqa, who is silent. Her bearded husband, dressed in a peacock blue shirt, clutches her hand and talks into the phone in Hindi, leading her into the gift shop that sells jewelry, scarves, neon nail polish and even ginger ale.

The hospital is milling with patients. The distant stink of disinfectant, saline, pus, and urine greet you near the snack machines next to the emergency room entrance. You encounter the highest concentration of hijabis you have seen in Manhattan in the past decade, both among hospital administrators and patients. The white hallway you turn into has welcoming sunflower yellow doors. Behind them are departments for child protection services.

Located on the seventh floor of the vast hospital complex, the Survivor’s program offices boast children’s crayon drawings, pinned to a wall. Tibetan flags and colorful depictions of Buddha peek from various offices to greet the survivors. On a board next to a book case filled with French titles and Diderot’s writings, is a billboard with five file folders, one for each NYC boroughs, listing their tourist attractions. A poster indicates that the fourth Mondays of the month are for art therapy.

The psychiatrist you meet is a tall brunette with kind eyes and a ready smile. She asks you basic questions about your healthcare, and proceeds to tell you that you can receive urgent health care as is necessary by walking into the emergency room, but that the wait to enter the SOT program is eight months long.

How will you get through eight more months without healthcare? You realize you have expressed your thoughts aloud. You need the nightmares to stop, to go through a day without bile in your throat.

“The emergency clinic will see you at any time,” the doctor says. She sends you in the direction of the SOT program coordinator, who prints a letter for the business center that says you are a program applicant. This allows you to have a Bellevue insurance card with a green sticker, that indicates you are a torture survivor.

You walk over to NYU’s dental clinic the same day. There, emergency room doctors decide – after you nearly jump out of your chair when the chief surgeon pokes your gums –that you have an emergency situation with one of your wisdom teeth. They operate right away. An hour later, you are back at Bellevue filling out the antibiotics prescriptions in a windowless hallway. You stand in line for two hours for the pharmacist to process your claim, blood jammed in your mouth as you clamp down your jaws to create pressure on the newly stitched wounds.

The local anesthetic wears off as you wait.

——————

At Bellevue, while you are waiting for your intake interview at the SOT clinic, you can sign up to see a primary care physician. The earliest date to see a PCP for a health exam can take up to two months to schedule.

One day, you find yourself unable to bear the bile in your throat. “You can have a seat,” the check-in personnel at the emergency room – a middle-aged woman and man – say in unison, when you check into the emergency room. Two blonde women are huddled in the corner of the waiting room, both charging their phones, but the rest of the room is empty. As is common in Bellevue, there is a police officer parked behind a podium at the entrance of the ambulatory care unit.

“I have a Bellevue card,” you say.

“That’s the best kind of insurance,” the woman responds. “What we like to hear.”

A page filled with stickers is printed out. One is attached to a band and strapped on to your wrist – the rest are kept in a blue folder. Your weight is checked. You are asked about your height, allergies to medication, and the ones you are taking – it’s routine procedure. You give the name of the pill that helps you keep the nightmares in check.

Past the waiting room, a wheezing woman breathes into a pipe on a chair. The scent of urine is stronger here. A curly haired blonde doctor tells her, “Does it feel any better now?”

The patient’s eyes are bloodshot. The nurses admit her. They wheel her past the ambulance drop-off area, which provides the only natural light in the emergency unit. Through the emergency doors, burly S.W.A.T. officers, surround an inmate, whose wrists are handcuffed to his emergency room bed.

You shudder.

After being examined, you are told to come back in three days for the Ear, Nose and Throat clinic. It takes an hour more for the doctors to schedule this appointment.

When you come out, it’s almost dinnertime, and you go to the neon-lit Moonstruck restaurant inside the hospital premises, which sells lukewarm oven-brick pizza.

——————

Three days later, you enter through Bellevue’s atrium to wait for your ENT appointment.

“We are an ally,” reads a television advertisement, showcasing Bellevue Hospital’s care for those who identify with the LGBT community in New York. Children’s voices reverberate in the hallway, a woman wearing a khaki jacket stares into her phone, waving her earphones as she speaks into her video screen. In the waiting room, 24 people of various ages are sitting. All stare at the lone television.

Congratulations on earning baby learning designation.

Learn about MITI- insulin programs you may be allergic to.

A receptionist with a blonde weave shakes her head at the growing line of those waiting to check in for their appointment. The nurse practitioner with the weave cannot tell you how long it will take for you to be seen. “Just ask the Asian guy when he comes back,” she says with her Trinidadian tilt.

No Asian nurse comes to the window in the duration of going to Hale and Hearty and buying soggy chicken noodle soup and a chocolate chip cookie.

You wonder if you will ever get used to your body’s protests against what terrorists have subjected your friends to.

Music crescendos on your return, advertising Metroplus insurance, which has a permanent booth in the hospital. During Christmas, a large Christmas tree covered part of the lobby, 20 feet tall and covered in baubles the size of your head. Today, there is art therapy for both children and adults. You remember how as a child, you never thought that you would go to the hospital except for checkups, certainly not to create art.

Two hospital workers sing Zayn’s “Pillow Talk.”

Mervin is a flu fighter. What palliative care can do for you. Get gym membership reimbursements.

A poster indicates that your healthcare is no good if it is an hour away on the G train.

Forty-five more minutes pass.

A bird is flying around the open atrium on the south side, trying to access the park on 25th and First, that is open to the public at intermittent hours.

During times of such long waits, Dr. Porterfield’s words reverberate, “If you can get used to the waiting, the service is free, and it’s good.”

When you are seen, the ENT specialist is a petite Indian-American. Her hair is in a neat ponytail. She examines your throat with a video camera, that she sticks down your throat through your nostrils.

It tickles.

“You have severe acid reflux,” she announces. She gives you a smile. She has completed the diagnosis. “I will prescribe you Nexium for two months. Just take coffee, wine, tomatoes, milk, cheese, all dairy, red meat, and chocolate out of your diet, and you won’t even need to see me again.”

This is America, the country that has made anti-depressants a multibillion-dollar industry of tranquilizers. Some doctors at Bellevue may remind you of stress-reducing habits such as taking walks, playing with pets, bicycling. Others express no visible qualms about omissions around probiotics, yoga, or lavender as a stress-reducing antidote to acid reflux and poor sleep patterns. It depends on the individual doctor, and possibly their trust in how well you know your self-care basics.

You sigh.

“It’s very common to have a physiological reaction to trauma, like the one you’re having,” the doctor continues. “Don’t be too hard on yourself.”

You wonder if you will ever get used to your body’s protests against what

extremists have subjected your friends to. Certainly, the recent terrorist attack was not an isolated incident of being subjected to abject violence in your life. Your cousin was murdered by her ex-boyfriend years earlier. An uncle’s tenant in his apartment building was killed by zealots. Another uncle was assassinated in a military coup. When the degrees of separation from you and those who have become victims of violence are nullified, your body faces a shock to its core understanding of purpose, for all the roads before you are uncharted.

“I’ll go get the prescription for the acid reflux filled right away,” you say.

On your way to the windowless pharmacy, you pass a mural of the New York skyline. As you look at it you feel safe in Bellevue, despite appointments

taking up the whole day.

An hour later, when you have picked up your prescription and you step outside the hospital’s windowless pharmacy, the first cherry blossoms are pale against the setting sun. As you walk past them, you remember how much your murdered friend loved flowers.

You stand underneath the blooming tree, and look up.