Life is getting sick and dying. Life is suffering. And that’s ok.

May 14, 2021

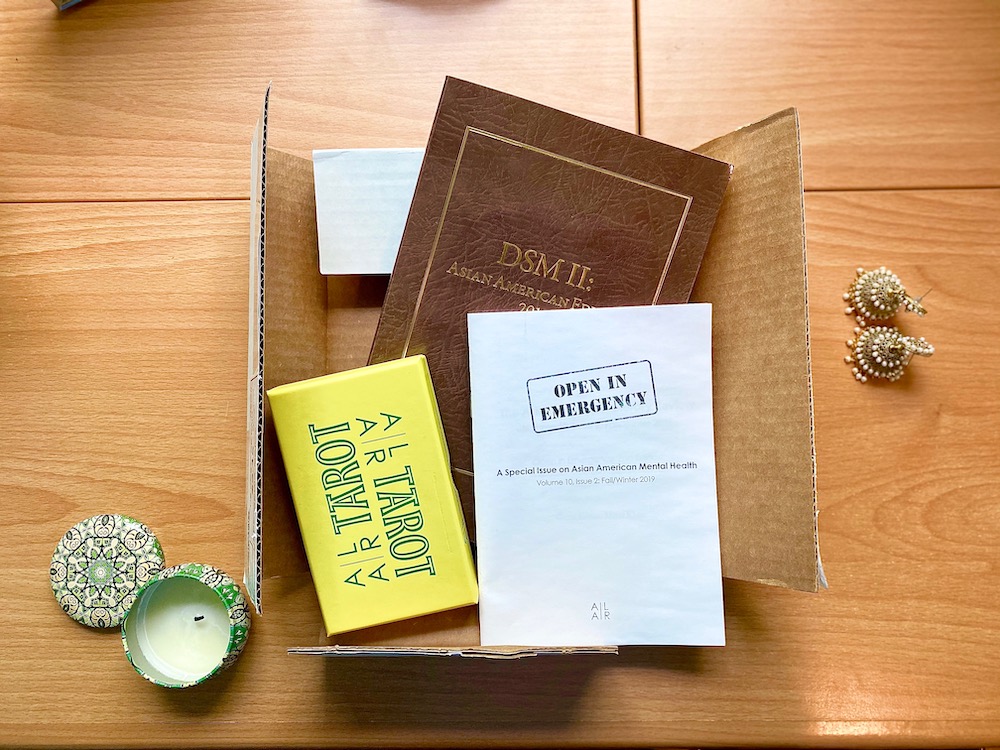

A few weeks ago, I found a box on my doorstep. It was a simple thing, white and made of cardboard, with frayed edges. On its side it had three words: Open in Emergency.

This box and its contents are the brainchild of Mimi Khúc, an Asian American scholar and Managing Editor of the Asian American Literary Review (AALR), an arts nonprofit based in Washington DC. It is a mental health intervention, designed to force Asian Americans to collectively ask, what does unwellness look like in our community?

And when we’ve identified our sores and burns, how will we tend to them?

The project was originally released in late 2016, at a time when Mimi and others at the AALR felt that our community needed alternative ways of healing. It sold out almost immediately. Now, amidst a pandemic that has sapped so many of us of our strength, AALR is bringing Open in Emergency back. This re-issue contains new ideas and new work.

I’ll admit I was nervous to open the box for some time. I allowed it to languish on my kitchen counter, and later my dining table, where it stared back like some forbidden book from The Chronicles of Narnia. I’m not quite sure what I was afraid of, but I felt daunted by its premise. Open in Emergency. What, exactly, constituted an emergency? Was I in one right now?

I couldn’t resist the temptations of a box whose contents promised so much—to be unapologetically about mental health, and unapologetically Asian American. I had been to enough therapists to know what interventions typically felt like—sterile, clinical, colonial, and very white—so that my therapist felt like an anthropologist, not a partner, poking and prodding, asking odd questions, trying to discern the meaning behind this specimen, this foreigner from another culture.

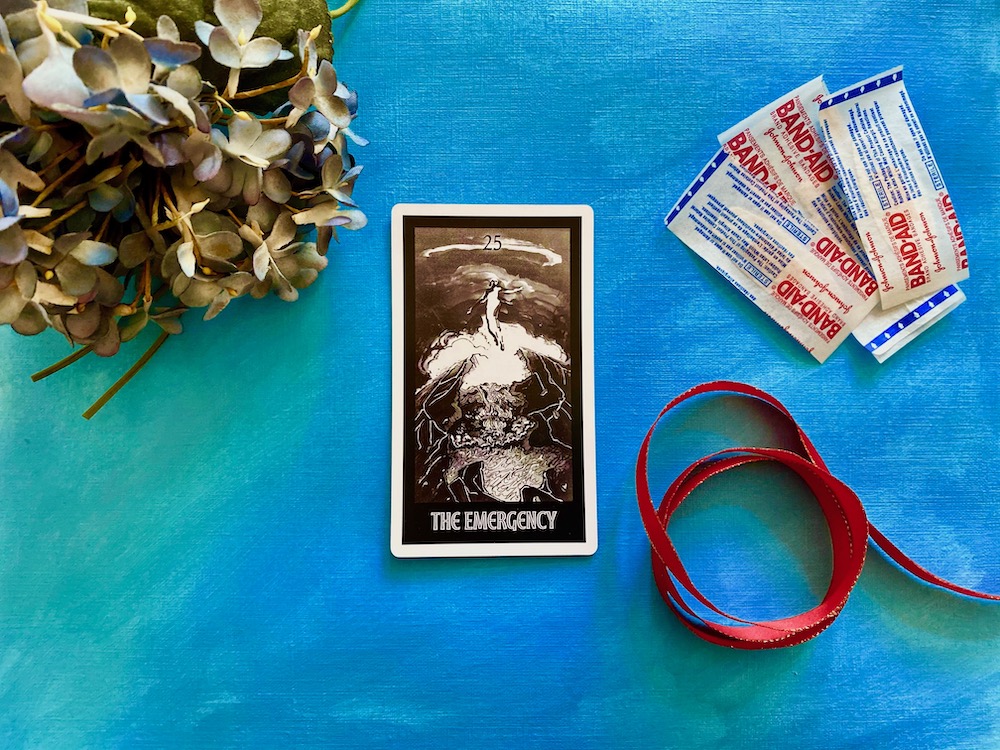

I’d find, eventually, that the box contained a handful of things, not unlike a first aid kit. A book, a pamphlet, a deck of tarot cards. In the coming weeks, I’d burrow into them, spending long nights reading the essays of Open In Emergency’s many contributors, thinking through their stories, their life experiences.

The opening essay in the book is by Kai Cheng Thom. In it, she recounts the night she tried to kill herself, just a few days before taking the SATs. I can’t stop thinking about something she wrote:

What if, instead of asking how mental illness can be contained or eradicated, we asked instead how it can help show us what kind of healing we really need?

What if, instead of clinging to the fantasy of mental health in order to deny our suffering, we asked our suffering what it is trying to say?

If you are ready and willing, this is the promise of Open in Emergency. To find your wounds, so that you may ask of each of them, what are you trying to say? When I finally spoke to Mimi, the guest editor of this project, she made one thing clear—Open in Emergency will not cure you; it will not fix your traumas or erase your pain. This is not a treatment, but an experiment: an experiment in storytelling and community sharing as a therapeutic approach, of trying to use your own memories, and the memories of others, as a way to figure out how you feel.

Below is a transcript of my conversation with Mimi Khúc, the guest editor and visionary of this project. I called her early on a Wednesday morning, as I was cracking open the project’s tarot cards. Staring at me was The Ghost. I smiled, because what else were Mimi and I doing this morning, but revisiting our ghosts?

This conversation begins as Mimi is telling me the story of her postpartum depression, which hit her hard after the birth of her daughter. She couldn’t sleep. She struggled to eat. She felt achingly alone and terribly angry, angry at this person that was meant to fill her with joy.

Our conversation has been gently edited for length and clarity.

—Preeti Varathan

Mimi Khúc (MK)

I felt like the language that was available to me to explain why I was suffering was not enough. I mean, the only language available was that I was a terrible mother. And that’s a deeply unsatisfying explanation, right? It was unacceptable as an explanation for why I hated my life. Four months into having my daughter, where was the joy that I was promised? I tried to explore then why life felt so hard and terrible.

Preeti Varathan (PV)

How did things begin to change?

MK

Well, eventually, I searched for a different language, a new language with new tools to understand my suffering. I realized that I could draw upon some of my training in Asian American Studies because Asian American Studies helps us think about historical and cultural contexts, systems of power, cultural discourses and racism. And those tools helped me build out a much better way of understanding my suffering than “I’m a bad mother” or “I’m simply experiencing a chemical imbalance,” which is kind of the medical, psychiatric way of explaining mental health issues.

What I realized is that mental health is not simply an individual pathology, to be treated or cured medically, but that it is something shaped by conditions around us and deserves support structurally, through collective care. And so, I wanted to create a project that could speak to all these different sufferings that I’d been witnessing, that could give us a broader, more capacious language for capturing and imagining our wounds.

PV

And that thinking, in many ways, is the genesis of this project, Open in Emergency. I’m making my way through it right now, Mimi, and I’ve tried to explain it to my friends, but it’s not this simple thing, is it? Every time I tell them, “oh, I’m reading this book,” I feel like I’m underselling it! How would you describe Open in Emergency?

MK

I’d start by saying it’s a box, not a book. And then the fancy way, you know, of saying it is it’s a hybrid book arts project. Some people like to describe it as a toolkit, or a care package, which I like because this thing is filled with tools. A book should not be something we just read. It should be a philosophical venture, something you can use in your life. This project is meant to be used. It’s meant to be imbibed and figured out and made useful on the journey of taking care of yourself and taking care of your community. And that’s why it takes all these forms, forms that involve theoretical interventions, but also practical interventions, that you can use in your life.

PV

Why call it Open in Emergency?

MK

So, there’s two interventions in the name, “Open in Emergency.” One is that I wanted it to be something you open, right now, that the directive is telling you to do something with this thing. And the other is the “emergency” part. Because part of this intervention is the claim that we are all unwell, in different kinds of ways. And that is its own fucking emergency.

PV

This is one of the major themes of the project. That we are all unwell. Mental illness is not something that just plagues a few and the idea of wellness, even, is a construct.

MK

Absolutely. A term that I use is compulsory wellness. Compulsory wellness tells us that we have to pretend to be well all the time. That being well somehow makes us good. And when we conflate wellness with goodness, it becomes prescriptive. And so, we don’t admit that we are unwell, because being unwell signifies a failure somehow.

PV

Is wellness weaponized?

MK

It’s totally weaponized! That’s a great way of framing it. It’s weaponized against us because we treat it like an imperative. The way we understand wellness is deeply capitalist. It’s about productivity. And we think we’re well when we’re able to work, or that we have to be well, so that we can work. This relationship between wellness and work becomes really fuzzy and crazy if you think about it. We get well so that we can work, we work so that we can pretend that we’re well. If we can work, nothing is wrong with us, right?

And so, with this project I want to give people permission to claim unwellness and to allow themselves to say, shit is not okay, I’m not okay. Wellness doesn’t have to be an imperative and it doesn’t have to be the goal. I want people to use this project to ask themselves: what hurts? How am I suffering? And to not feel ashamed about that. When I say “open in emergency,” I’m actually inviting everyone to open it right now. Because you actually are in an emergency, whether you want to admit it or not.

PV

This is a re-issue of the original project, and it feels especially timely, since we’re in the thick of a pandemic and growing violence towards our community. Why did you decide to bring back Open in Emergency?

MK

Well, the first edition was wildly popular and sold out that same year. And then we just kept getting more requests. People wanted to teach it. But we knew if we wanted to make more we’d be up against some limitations, especially money, since the first issue took around $30,000 to create. And the whole thing was crowdsourced. Eventually, we did decide to expand, to work on a second edition. So, then I started to ask myself, what was missing in the first edition? What were some gaps? What new kinds of conversations do we want to engage in? Who are the cool people we didn’t know about before that we must talk to this time? As a result, this new version has more contributors, more essays, and we added seven new tarot cards.

PV

The editor’s note for this project is written by you and it is a letter to your daughter. It’s pretty intense. How does that letter set the tone for this project?

MK

Well, I wrote that letter to think about what I’m trying to pass on to my daughter. I’m trying to tell her how to save her own life, because I’m watching everyone around me die as they’re navigating the racism and ableism of their lives. And so, to raise a daughter, an Asian American daughter, especially, in this context, means giving her the tools to survive the violence around her. And so, as I was writing it, I thought, okay, this is a good opening for the project because these are the stakes. The stakes are deeply personal to me. They’re life and death. In a way, I’m gifting this project to my daughter.

PV

Mimi, I know this box isn’t exclusively for Asian Americans, but it does intimately reflect the Asian American psyche and our community’s state of mental health. How do the different elements of the box speak to this identity?

MK

Well, a major origin point for this project was my students. I’ve been working with Asian American students for a very long time. I’ve seen their suffering. I’ve come to understand why Asian American students have some of the highest rates of suicidal ideation among all students. And so, for instance, when we were creating our tarot cards, I wanted to think about what this set should offer. Tarot actually comes from medieval Italian playing cards, and that’s very European, right? So the way that we approached these cards was by drawing on Asian American categories. We created The Refugee, The Migrant, The Ghost, but my favorite card is The Student. It was actually written collectively by dozens and dozens of students. It’s the only card that was written in this way, and I think it’s really rich and gut wrenching if you read it.

PV

You call the box’s book of essays an Asian American Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM). To me that’s a really interesting choice, because Open in Emergency seems to reject purely clinical notions of mental health, and yet, you’re co-opting that kind of language.

MK

Yes, it was a very deliberate choice. The Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders by the American Psychiatric Association is the mental health Bible. It’s supposed to say what disorders exist and the right ways of diagnosing them. But, in reality, the way we do diagnosis is incredibly limited. So, what if we were to make our own DSM? What if we were to diagnose our own suffering as a community and our own ways of caring for that suffering? So, we imagined ripping out all the pages that could have existed in an Asian American DSM and sticking in our own pages as a way to diagnose ourselves.

PV

It feels like the goal of Open in Emergency is to ultimately change how Asian Americans view their own mental health. But it’s not intended to be curative, to promise you that you won’t feel any pain at the end of this journey. Why isn’t absolving our suffering, our struggle, a goal of this project?

MK

I’m going to be referencing the work of Eli Clare here. Eli Clare is a Disability Studies and justice writer and he’s really helped me crystallize the critique of cure. To cure implies that there’s a pathology that should be removed, eradicated, or excised. It also assumes there’s some kind of normal state that you can return to, there’s a healthy state to be returned to and be made whole. But life is getting sick and dying, life is suffering. I mean, think of The Princess Bride quote, “Life is pain.” Anyone telling you different is trying to sell something to you. We cannot return to some supposed state of non-suffering. You work through your trauma not by erasing it, but by figuring out how to move in the world with it. And so, in that sense, Open in Emergency wants to show you how to move in the world as you are suffering, because we will always encounter more trauma, new trauma, different traumas.

I will leave you with the words Mimi wrote for her daughter:

This thing called Life is no joke, my sweet child. It is ok to hurt. We must allow ourselves to hurt, to trace the losses, the heartbreak, the death. We must allow ourselves to be whole people, in all our brokenness. Our lives as always negotiating violence, trauma, crises of meaning. Our lives as always finding new ways of making meaning, making commentary. I tell you this to free you, but to also show you how to allow others to be free.

In your hands is a project I dreamed, for me and for you. For the brokenness we all share, so different and so similar. I dreamed this project to save my own life. To help others save their own lives. To help you save yours.

Open in emergency, my darling.

It’s an emergency. Right now.

You can find Open in Emergency on the Asian American Literary Review’s website, here.