I might do something dangerous in that state of mind.

December 11, 2020

Yesterday, awakening to the world, I saw the sky turn upon itself utterly and wholly. I wanted to rise, but the disemboweled silence fell back upon me, its wings paralyzed. Without responsibility, straddling Nothingness and Infinity, I began to weep.

—Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks (1970)

George Floyd was murdered by the Minneapolis police on my birthday. The news came to me first from my mother, who simply sent a reminder to all of her children saying to be careful in the streets, and that she loved us more than anything. I remember hearing that George Floyd cried out for his mother with his final breaths. I could relate to him most in that moment. I did not, and still have not, watched the video recording his death. I’m not able to hold images like that, they get too deep under my skin and make me want to crawl out of it. I might do something dangerous in that state of mind. So I didn’t look. It honestly didn’t even register to me as a significant event in U.S. history. It felt like just another day in America.

Drinking tea at home in the early weeks of quarantine, friends and I would laugh and joke on Zoom calls about the collapse of the state, which seemed to coincide with the upcoming election. It was increasingly clear at the time that Joe Biden was going to get the Democratic presidential nomination over a slew of other more progressive leaders. When friends and colleagues would suggest that now we “had to vote for Joe Biden,” I found myself inexplicably emotional.

“I won’t. We don’t have to do that!” I would plead with them, feeling myself near tears.

“What other choice do we have?” they would ask me. “There’s no other option.”

Tensing my body, I would insist. “We have options!”

“Like what?” they would ask, clearly not convinced and seemingly unconcerned.

“A coup!” I would answer.

They humored me, but it was clear that they did not believe in the reality or possibility of anything I was saying. The isolation was suffocating. After we would end our calls, I would close the computer and allow the tears to fall onto my folded hands; a prayer for the end of the world.

A few days later, my partner and I took a road trip south to meet up with my closest friend in a cabin in the woods in Virginia. On the morning that the Minneapolis precinct was burned to the ground, she burst into my room like Christmas morning, beaming from ear to ear as she handed me a cup of coffee.

“They did it! You’re gonna love this! Check out Minneapolis, they set fire to the whole precinct!”

Ignited, I was driven to take a detour to Washington D.C. on my way back to New York City. Arriving in the capital, we came immediately upon a massive and militant march circling the White House. Taking to our feet, we allowed ourselves to be swept up in a wave of energy and emotion. I felt a light that I had not even realized was wavering suddenly reignited in my chest. I’ve been chasing that feeling every night since; moving under the cover of darkness, protecting the flame.

After they ran us out of the park, we were forced to stay out. As they pushed us out, they moved in.

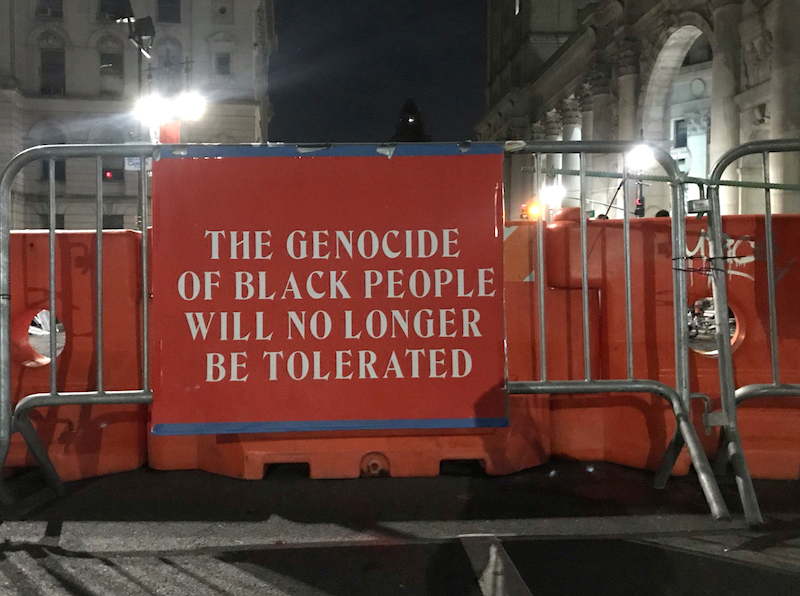

Weeks later in New York City, this energy drove people out into the streets night after night, even as our bodies and voices broke down. The more the police tried to separate people protesting, the closer the crowd grew together. The more violently they tried to repress our demands, the more power and conviction we brought in response. The massive scale of the NYPD was revealed in brutal and horrifying displays of force. Many of us were caught a little off guard at first. Wait, how many police officers are there? How much money do they have!? How many helicopters? How many guns? But after allowing myself to express the fear and passions I was accustomed to withholding, I couldn’t imagine going back to living “peacefully” under the familiar dead weight of oppression. I could not unimagine a way out.

On June 23, someone sent me a message asking, “Can you pull up to City Hall to help set up a camp? We need at least fifteen people to stay the first night.”

Just a few weeks prior, folks in Seattle had taken control of an entire precinct and effectively pushed the officers out to create an autonomous zone (known as CHAZ) separate from police and law enforcement. Many New Yorkers had been discussing establishing something similar in our city, and I was intrigued by the potential of such a space.

When I arrived at City Hall there were hundreds of people dancing in the street. The original conveners of the encampment had led a large march over the Brooklyn Bridge that ended at the steps of the Tweed Courthouse. However, as the night stretched into morning most people went home. By the end of the first night, about twenty of us remained. We set up camp by sitting on the lawn, resting our heads on our bags or in the grass. At some point in the evening, a notice went out on Instagram asking for supplies to support protestors who were planning to #OccupyCityHall. Within hours people started dropping off blankets, food, and books, paired with encouraging hugs and smiles. As we lay in the dark, one young black woman carrying a Haitian flag and a megaphone spoke to us. Her oratory lifted us to a suspended state, caught between night and day. I didn’t sleep. I remember drifting in and out of consciousness, wrapped in a blanket given by a stranger, carried by her voice. She preached and sang well into the early morning; the first of many mornings we would see the sunrise in that park. The thing I remember most about that night was that she sang a slow, languid version of happy birthday to Tamir Rice. I couldn’t think of a more fitting tribute.

The next day more people started coming. A library was set up. Then we had a bodega. By the end of the first week, we had a laundry service, a mental health tent, and a garden. People were pulling up and doing whatever they wanted. I recall an overwhelming abundance of energy and resources. A black woman with experience in the restaurant industry quickly started establishing a food infrastructure. She put up some cardboard signs for crowdsourcing donations and was able to fundraise nearly $30,000 in two days; effectively coordinating 24/7 meals for everyone in the park. Luxurious, gourmet food was purchased from or donated by local restaurants: shrimp salads, grilled sandwiches, chocolate cake, endless vegan options. Bodega supplies also came pouring in, and everything was free. Take what you want! Gatorade, water, coolers full of ice. Come get a sleeping bag or a tarp! People started to get comfortable.

The initial resistance against the encampment came from activists organizing marches in the streets. At that point, there was a march for Black Lives in every borough every night. With the establishment of the camp, the energy that people poured into marching was being consolidated in one place, which generated some negative feedback from our comrades. From the outside, it looked like people were just hanging around, not doing anything meaningful. However, being in that space was a deeply moving and immersive educational experience. The park was a public classroom with around-the-clock political education. Innumerable critical dialogues were happening spontaneously; people were becoming radicalized just by walking through the space. “Wait, did you know the NYPD had this much money? Why don’t we have money for health care, or education, or housing?” These were shocking realizations to people, and these dialogues marked an important turning point in how the public related to the budget of New York City.

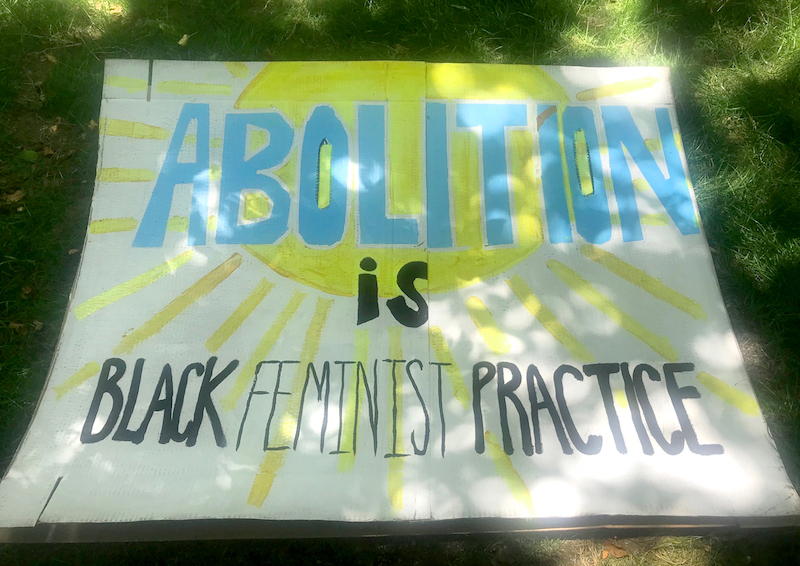

I wanted to recreate a teach-in at City Hall titled “When is Reform an Obstacle to Abolition,” as a follow up to a well received teach-in introducing abolition that some comrades and I had given a few days prior in Bedford-Stuyvesant. Many activists gathered at City Hall were dissatisfied by the limited call of “Defund the police by at least a billion dollars,” and wanted to mobilize a stronger push for “Abolition now!” However, so many people showed up for the teach-in at City Hall that there was not sufficient space for us to gather. A comedy show that had been formally listed on the “activity schedule” was happening in the center of the park, the most ideal space for a crowd to meet. The result was about a hundred of us milling around looking for a place to dialogue.

Looking around the overcrowded park, I said to everyone, “We can try to fit in here on this grass and ask people to move over, or we can go to the bridge, because f*** it, it’s our bridge.” Immediately, the crowd responded, “TO THE BRIDGE!!!” and started running towards the entrance of the Brooklyn Bridge, shouting over their shoulders for other comrades in the park to join them. Many people followed. The energy of the crowd was, we’re taking this bridge.

We flowed out into the intersection, hopping over the barriers from the pedestrian walkway down into the road, stopping traffic. We marched across the bridge from Manhattan all the way to Brooklyn, and when we found the police waiting for us at the Brooklyn exit, we climbed the barriers to the opposite lane and marched back to Manhattan against traffic, shaking our fists and our asses at the police tailing us, stomping and shouting loudly enough to be heard from either side. When we reached the Manhattan base of the bridge, surrounded by clearly agitated police, we sat down on the walkway and continued our teach-in. The police were forced to listen in.

Spirits were high. We generated so much energy and intention and power in that march, that it proved to be a key moment of community formation. Most of the people who came for the teach-in and ended up “taking” the bridge together are currently still organizing towards their political goals as a collective known as Abolition Park.

When we returned to City Hall, the original conveners of the encampment were angry. They argued that we did not have consent to take that action, that we brought an increased police presence to the perimeter, and that the action encouraged people to leave the encampment when the intention was to hold the space. This tension caused an immediate, visible split. It was contentious. There was both resentment towards those who didn’t heed the call to take the bridge, and from people feeling that we betrayed the original intention of the encampment when we left the park. It was a real-time role play of how reformist and abolitionist political strategies often don’t work hand in hand. That was only the third day of the encampment.

By the following day, we quickly realized that we did not have time to fight with each other because we needed to focus all our energy on fighting the police. On Monday and Tuesday before the city council budget hearing, there were two back-to-back police raids in the early morning hours. Residents of the park moved to form a human chain, linking arms and using bodies, shields, bikes, and barricades to hold a perimeter while the police literally beat us back. The morning of the first raid, I got a black eye from being hit in the face with the back-end of a police baton. My eye was black for a week after that, and it was eerie how easily that became normal. Although people were injured, pepper-sprayed, and exhausted, the NYPD was not able to enter the park.

Footage of the police brutality circulated in the news. It looked so bad that Mayor Bill de Blasio released a statement telling the NYPD to leave the encampment alone until further notice. This was certainly a victory, but the NYPD remained an ominous and threatening presence.

The night of the city council vote when the obvious became more obvious (they were not going to cut any money from the police budget) was supposed to be the last night of the encampment.

In the morning most of the original organizers took their resources and left, but hundreds of people chose to stay. At that point, a lot of conversations needed to be had. We were strangers gathered in a park and we didn’t really know why yet. We didn’t know how we were going to survive in such an unpredictable and volatile space. What we did recognize was that without the resources that we needed, the park would become increasingly dangerous for everyone involved. All the infrastructure around food, donations, and supplies had to be rebuilt from scratch. We were thrown into immediate crisis response.

The most significant, and in my mind, the most meaningful, shift that happened at City Hall was the transition of occupants at that time: the composition switched from a group of people who all had another place to live to folks who had nowhere else to go. This could also be framed as a transition from a park full of people who took safety for granted to a park full of people who had been exposed to violence their entire lives. This could also be framed as a transition from a park full of people who were there because it was popular, to a group of people who were there when living there was considered shameful and disgusting. These shifts were so important because they really pushed the work in a more radical direction. We evolved from a comfortable, even luxurious camp that advocated for moderate reform, to an urgent demonstration of why and how the police are a threat to our everyday safety. Instead of speaking for, over, and down to the most vulnerable and disenfranchised people in our city, we welcomed them and enlisted them in the fight for their own liberation. We went from theory to practice. That transition in itself is a victory in my eyes.

There have always been unhoused people living at Washington Square Park, but if you give them any shelter, it’s unacceptable.

I stepped into the role of facilitator. I began facilitating community meetings on a daily basis. It started with a morning and evening community meeting, twice a day for a couple of weeks. Once we became more confident in our ability to self-organize, we shifted the meeting to every few days, and then eventually every few weeks. At first, the meetings were very tense gatherings. They were opened up as forums for people to voice whatever people had to say. I found my responsibility as a black woman and a feminist to be modeling a radical way of being in relation to others. Some days I was able to provide a consistent, grounded energy to counter the explosive hazards of patriarchy and anti-blackness. Other days conflicts erupted into violence. We all had to learn very quickly how to manage our emotions under extreme circumstances. It was a very condensed crash course in conflict resolution.

I overheard someone else using the word “de-escalation.” I didn’t even know I had the ability to do that work, but it was necessary. That role led me to identifying and reaching out to other people whom I saw also doing the work of de-escalation and us starting to meet to share strategies for community safety.

One of the things that was really helpful and that I saw other people learning and applying was that there had to be an understanding and compassion for someone else’s trauma. It required stepping back and saying, Yes, I am able to recognize that I’ve been harmed by this person. But I am also able to find compassion for the trauma that may have brought them to this place. I am going to recognize the root of violence not being here in this immediate interaction. That it’s deeper than this moment.

It was also about self-accountability and recognizing that when it comes to de-escalation, it’s really about your own body. I learned that in moments of crisis, de-escalating volatile situations will always be about my body and what I can make do, not what I can make someone else’s body do. I can calm my body, calm my voice. Bring my energy way down. Find something within myself to hold onto that is centering. Don’t try to overpower anybody. Taking control of a heightened situation is not about trying to be bigger, or stronger than someone. Prioritizing consent was a big part of the conversation.

Another thing we learned that helped when we got it right was not to be a voyeur to someone else’s pain. When someone is in a heightened emotional state in a public place, they start bringing attention to themselves, intentional or not. Typically, people will rush over to see what is happening and escalate that energy, like putting gas on a fire. Alternatively, if you redirect that energy and everyone moves in the opposite direction, a situation is much more likely to defuse itself. Moving away also creates a safe space for the necessary expression of the completely reasonable frustration that so many of us felt. By keeping our distance, and allowing a person that autonomy, we provided ten secure square feet for a person to lose their shit.

Don’t try to stop it, don’t try to control it, don’t penalize them for it. If we stay over here, they’re not going to hurt anyone. They’re going to yell and scream and maybe smash a chair.

As a community, we had to agree that we were not concerned about broken chairs because we could get more chairs. We kept repeating over and over we weren’t going to police property. If you lost something in the space, then you lost something in the space. It wasn’t a thing you could bring to the community seeking punishment for someone else. Do you need a phone? We can get you a new phone. Do you need a new sleeping bag? We have more sleeping bags! We learned to address the violence that comes from scarcity with resources and abundance instead of shame and punishment.

We know that’s not how the cops respond. We’re watching them watch us. They’re so easily triggered. We found that simply inverting police behaviors and the carceral logics that motivated them resolved a lot of our issues. In this way, we were able to keep the park free of police for almost 30 days—until 3:40 a.m. on July 22 when we were raided and violently evicted from our home.

The night of the final raid, the police used a different tactic than before. Without warning or a sound, they rushed and shook sleeping people from their tents. Within minutes, they had swept us all out of the park. There was no announcement, no opportunity to prepare.

Many people living in that park lost everything they had to the NYPD that night. I am referring to poor and unhoused people who lost their legal documents, phones, photographs, family heirlooms, valued possessions—all the precious and sentimental things an unhoused person might keep with them. The police also seized all of our bikes, medical supplies, generators, coolers, and stacked pallets of water into their custody.

After they ran us out of the park, we were forced to stay out.

Officers followed us into the street, scattering and arresting people; snatching people for contesting the raid or just standing around too long. We fled with no real sense of direction because there was nowhere to go. We could not have returned to City Hall because the NYPD immediately occupied that space.

As they pushed us out, they moved in. The New York City Police Department has maintained a presence of hundreds of officers at City Hall Park since that night.

It became increasingly risky for the people who are visibly and vocally protesting the unchecked power of the police to stay on the street because the police terrorized them.

At this point, we were a displaced community of recently robbed, brutalized, and traumatized unhoused people that needed immediate food and shelter. The people I escaped with were a ten-year-old boy and his mother, a man and his wife who hitchhiked from Indiana, and a young black woman who had just been released from jail a few nights prior. While I knew that I could go home eventually, I had no idea where any of the others could safely retreat. It was obvious that we couldn’t keep wandering the streets, because the cops were out there grabbing people. In the immediacy of the raid, where could we go to be safe? The necessary solution required so much of our housed community to open their doors. It was urgent.

I started calling people, “Can so-and-so come to your house tonight?” Or just showing up, “We’re outside.”

That night made the connection between abolition and housing justice painfully clear. Moving forward, housing and ongoing mutual aid became the need that we continued to organize around. How could we find safe housing and continue to provide the services that were provided in the park: daily meals, medical care, community? How would we continue to provide those things without space to gather? We struggled to determine how we might sustain the networks of care and resources developed in the park without a central location.

In the immediate days after the raid, most of our community relocated to Washington Square Park. Miraculously, we had just ordered forty yellow tents, which at the time of the raid were in storage at a nearby office. At Washington Square Park, we started handing them out to people who lost their homes when we were evicted from the City Hall.

This was too visible for the cops.

There have always been unhoused people living at Washington Square Park, but if you give them any shelter, it’s unacceptable. At City Hall, many people had tents or built other structures for shelter, but there, we had the numbers to keep each other safe. At Washington Square, the police were able to quickly and violently break up smaller groups of one, two, or three tents together. Every night and day they would make arrests until it was no longer viable for us to be there. The same officers that had been surveilling and threatening us at City Hall showed up at Washington Square Park to continue policing our gathering. Washington Square Park became a place you could go to get arrested, and that’s it.

I don’t see any of the yellow tents around anymore. I’m sure the cops got them all.

Recognizing that small groups of unhoused comrades living in tents was not viable, we started crowdfunding for hotels and Airbnbs to house people. At the same time, community members from the park with housing continued to open up their doors. Some brought even four or five people home with them. That wasn’t sustainable but it was an immediate solution.

In terms of assessing need, we knew a number of young black girls who did not have access to safe housing. Importantly, they had identified the camp at City Hall as one of the safer places they could reside. When our park was taken, they were our immediate priority when it came to securing housing. A large number of our unhoused community members were also older black men, most of whom had already been incarcerated at some point in their life, and therefore whose freedom and autonomy under constant police surveillance was very precarious.

It was overwhelmingly young women who opened their homes. Those with the most secure housing were women—white, college-educated women in their early twenties and black women over 30. Collectively, these women were able to house a lot of the men, creating complicated gender dynamics.

When you have one woman who brings three, four, five people home and four of them are men, there are concerns about that kind of intimacy being misread and misinterpreted. It’s a very big risk for a woman to bring an unfamiliar man into her home. Although I am not aware of any instances of violence or assault that happened in that context, what did happen, and what always happens is that those women get really fatigued by the burden of caring for everyone.

Stepping into this maternal role of being the provider and caregiver always increases the risk of burnout and exhaustion. A woman might not always say it for herself, because there’s a lot of guilt around privilege and there’s guilt around women saying, “I don’t have this capacity. I’m tired of housing, feeding, and tending to this entire community.” You don’t want to reproduce harmful gender dynamics in mutual aid but it’s really hard not to. That was a real challenge.

Getting unhoused people living with others out of people’s houses happened slowly. It required assessing who was under the most pressure and trying to relieve that pressure by finding the people they are housing somewhere more sustainable to stay. Meanwhile, we continued to take to the streets every day, engaging in intense stand-offs against lines of police in riot gear, publicly demanding the immediate defunding, disarming, and dismantling of the New York City Police Department.

The connections between safe housing and abolition may not have been so immediately obvious if we were not seeing them in such visceral and immediate ways. Not having safe housing clearly meant being more susceptible to state violence.

At City Hall, when we erected structures that offered coverage from sun and rain, the cops used that as a reason to raid us because it’s illegal to construct your own shelter. When we gave out tents, the cops arrested people for sleeping in them and took those tents away. Then, as we were renting Airbnbs, paying months in advance, we would check-in only to have homeowners cancel the reservations, telling us, “This isn’t a homeless shelter.”

So you have to not be homeless in order to be eligible to stay in a home?

Such precarity on a day to day level makes it much easier for comrades to get caught up in the punitive and carceral system. Without the safety of shelter and community, people are much more exposed to police surveillance and brutality.

It became increasingly risky for the people who are visibly and vocally protesting the unchecked power of the police to stay on the street because the police terrorized them. We became vocal housing advocates because the police were targeting our most vulnerable community members in an effort to weaken their commitment to a fight for their lives.

Six months later, as we enter into the cold winter months, police surveillance of protestors has increased, and the housing crisis in New York City worsens. Housing Courts are preparing to evict tens of thousands of New Yorkers in the coming months. Already, there are three empty residences for every unhoused person in the city. Abolition Park continues to provide safe housing for our community while publicly demanding safe housing for all New Yorkers. We also have a dedicated food team committed to reducing food scarcity by providing nightly community meals free to the public. These are not supplemental or peripheral activities in our fight for black liberation. The abolitionist principles that we learned from our experiences in and outside of the camp demand that care (not cops) is at the center of any political action we take.

We constantly change the location of our community meetings and dinners. We try not to use the same spot twice in a month because we get a lot less police surveillance if we keep it moving. Police surveilling a dinner might seem innocuous but people keep getting arrested. The police seem very threatened by our ongoing mutual aid.

We started moving every day.

That’s still where we’re at.

This essay is published as part of A World Without Cages, the Asian American Writers’ Workshop’s ongoing project on The Margins that imagines the end of mass incarceration and migrant detention by bringing together the work of writers on the inside and on the outside. This project aims to nurture writers, activists, and intellectuals to dream new worlds beyond punishment, policing, surveillance, segregation, and exclusion. Read more in the project here.