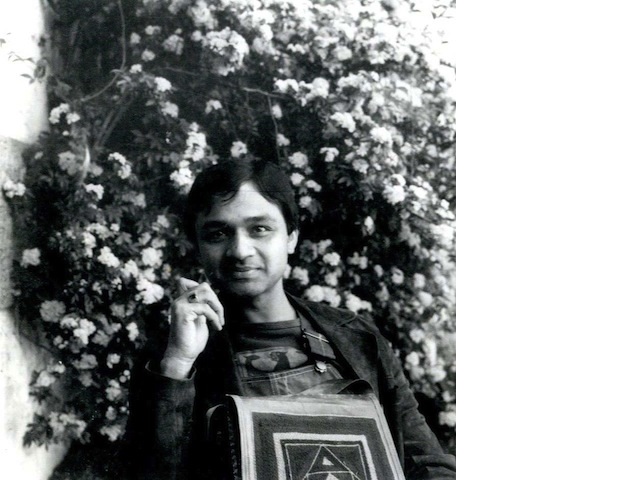

An interview with Akhil Sharma, author of Family Life, on how to write a novel that has no plot, literary modernism’s influence, and remembering India

April 11, 2014

Last Friday, I had the pleasure of sitting down with Akhil Sharma over a cup of tea to talk about his new novel, Family Life, out from W.W. Norton this month. Early on in our conversation, Sharma disclosed that he hadn’t read a single review of his book until that day, when a friend insisted that he glance at the cover of the New York Times Sunday Book Review. “It’s so weird to think it’s out in the world. I still keep expecting to have to edit it,” he confessed.

Sharma has been at work on the book for nearly 13 years. “I don’t really have a sense as to its merits or demerits,” he told me. It’s not only the passage of time that makes it hard to evaluate his novel, he implied, but also distance. “It’s so close to life.” Almost everything in Family Life happened to Sharma’s family.

The novel chronicles the story of the Mishra family, who move from Delhi to New York City in the late 1970s, soon after Prime Minister Indira Gandhi declares a state of emergency in India, suspending the constitution and dramatically curtailing civil liberties. They settle in Queens, and initially their story might sound similar to stories we’ve heard of other Indian immigrants to the US in the 1980s: of upward mobility, of seemingly boundless ambition. After months of studying, the family’s elder son Birju is accepted into the prestigious Bronx High School of Science. The Mishras couldn’t be happier.

But one summer day Birju has an accident in a swimming pool. He’s left severely brain damaged and blind. He cannot walk or feed himself. Ajay, the younger son, who is our narrator, is 10 years old at the time.

Family Life unravels as a wrenching, painfully honest portrait of a family trying to pick up the pieces and care for their son. It’s about how they relate to each other when nothing is the same again, and how Ajay, returning to these moments from his childhood, makes sense of who he is to his family and who he has become.

Akhil Sharma spoke to me about his relationship to remembering India, the tricks he learned to help write a novel that has no plot, literary modernism’s influence, and why he’d never write anything like this again.

Click here to read an excerpt from Family Life in The Margins.

Several years after Birju’s accident, Ajay turns to writing stories as a way to cope with what’s happening to his family. Ajay’s father, an alcoholic, doesn’t come home one night. It’s terrifying. And Ajay begins to write a story about a man who is waiting for his alcoholic wife to return home. “As I wrote,” Ajay narrates, “I felt proud at my toughness for taking whatever was happening to me and turning it into something else.” In writing this novel, did you find that you were doing something similar? Taking what happened in your life and turning it into something else?

When I was young, I took pride in being tough because I had no control over my environment. And so these horrible things would occur and I would convert them into art. Now as I’ve gotten older, I have no desire to be tough. And I find myself more and more tender. When I write now, I feel my sympathy pours out towards everyone. A woman just asked me earlier today about a point in the book when Ajay tells a man he meets at a gathering, “Oh my brother is not in a coma. He’s brain damaged.” [Ajay’s mother had been telling people she met that her son was in a coma, to allow for the hope that he’d recover.] She said, “Oh, it sounds like some anger on the part of Ajay.” I said, “Yea, and my sympathy goes to the man who’s hearing this story because what can he do in this situation,” you know? And who is he loyal to? Does he say yes, because then he’s going to be making the situation of the parents worse. As I’ve gotten older, my sympathy just spreads out a lot further than myself.

Ajay’s mother keeps the hope of reviving Birju alive through religion and faith, like the miracle workers who come one by one to try and “wake” Birju up. But Ajay’s response to the presence of religion in his family’s life is more fantastical. He begins praying to a Superman symbol, and talking to God, who in his mind looks like Clark Kent.

We all want to be comforted. Ajay wants to be comforted. He will pray. He will do whatever he’s told to do, partially because it’s an expectation, and partially because it helps him to do something. Even when we can’t actually do much to help, we want to do something. And then as he’s praying, he’s also aware that this is stupid. It’s not going to work out. And he has to make God appear more rational to him. And so he turns to Clark Kent. The miracle workers are similar. That is, they are ridiculous, but because each of them is new, there is that refreshing of hope that occurs when we do something new. That’s how hope is maintained.

Ajay struggles to remember India at various points in the book, whether it’s in the first few pages, as he notes the difficulty of imagining the Delhi of the 1970s, or later on in the US when he has this realization that his family would never go back to India again. He thinks to himself, “I would be nothing like who I was right then. It was like sensing my own death.” What is your relationship to remembering India, or how has it changed?

I remember when Indira Gandhi died, I was so excited to watch TV so I could have images of India. Because it had begun to feel imaginary. And then we had the Bhopal disaster soon afterwards. I wanted to write about a particular time in the Indian community, when the community was beginning to form. It was so exciting when you’d see another Indian. If you were driving—this is in Edison—and you passed another Indian, you would pull over to the side of the road, and cross over to talk.

I don’t want that lost. These things get forgotten. I was talking to this woman from India about the same age, and she said she had forgotten that they used to save the cotton in the medicine bottles. All these details are worth preserving. I think our community is worth preserving. So that was one of the motivations for writing this book.

As an artist, the India that I really know deeply is an India of a few neighborhoods, a few alleyways that I can really conjure up. I go to these neighborhoods when I visit Delhi and I know their history. I know what families have moved out, what families remain. So I write about that world. I wrote a story that came out in the New Yorker last June about this one alleyway in Delhi, and I just took it from my childhood in the ’70s to now.

On a related note, how did you handle reckoning with memories as you wrote? Were there occasions when you were not able to remember moments?

When I revise I don’t really revise, I rewrite. I just start from a blank page. And what I write down is the thing that remains. It’s the thing that I cannot forget in the story. That’s how I generate what feels essential. It’s the thing that cannot be forgotten. And so there were times when I couldn’t remember things when I was writing. And actually that was rare. What was more common was remembering things and excluding them. You can’t include everything, because it disturbs the pattern of the novel. And that is what I tried to protect—the pattern of the novel. It was tricky, because when you remove something you begin to wonder, am I being dishonest? Is the entire thing true? If I were to describe this room, for example, and not describe the fact that we are here having an interview, then it would feel dishonest, like what would be the point of describing this room? If you are dishonest in one way, it makes the pattern feel dishonest.

That reminds me of a tension that some autobiographical fiction writers have described, between the pressure to establish a plot in a story and the reality that our lives don’t always fall into clean narratives. Did you experience something similar in writing Family Life?

This book doesn’t have a plot line, it doesn’t have causation, which is how we define plot. Something occurs and then there are reactions to it, repercussions. And so you have to do certain technical things to make the absence of plot, the absence of causation work. Here, I would describe the room, I would describe you, I would describe the sound, I would describe the smells, I would maybe describe the temperature. And together it creates a visceral reality. That’s the default setting. But then you need the plot that will get you into this swamp—the swamp of this moment—and push you into the next moment. If you have a weak plot, that is weak causation, you can’t take the reader into this visceral reality, because it’s too sticky. So you need to thin out that reality. What I did was remove certain elements of the sensorium. There’s very little sound in the novel. There’s very little smell. There’s very little feel. Because those are the stickiest parts of the sensorium. What’s left is largely the visual. The dialogue serves as sound. And so you have a very thin sort of physical dramatized reality. At times it feels so thin that it seems fictional. And so then I put in other things to plump it up. I have these people’s comments and thoughts. And that’s what I used to plump it up. To make it feel more real.

Can you give me an example?

At the very beginning of the novel, when the father is outside on the roof, I don’t describe the smell of dust. Or what temperature it is. Or the sounds from other neighbors when you’re on the rooftop. It’s simply these people on a roof with the stars above them, and some dialogue. But what makes it feel real is the motivations of these characters, and the humor, and what these people are thinking.

Speaking of humor, some of the most difficult parts of the novel to read, of exactly how sick Birju was, is juxtaposed with lightness, with laughter. How would you describe the relationship between humor and grief?

You know that Beatles song “Help”? It’s sung in a very cheerful way, because if you sing a sad song sadly, it become dolorous. It’s hard for an audience. So you want to cut on a bias. When you’re cutting cloth you’re cutting against the bias. Because it becomes almost oily, the cloth. And that’s sort of what one wants. One doesn’t want to handle a subject in the way that the subject demands to be handled. Because then other characteristics of the subject jump out. If you were to handle the subject based in the way that it demands to be handled, it would become less life-like. It would begin to blend into the background.

At one point in the novel, Ajay, then maybe 12 years old, becomes fascinated with Hemingway. He reads volumes of literary criticism before reading any of Hemingway’s own work, and starts writing short stories of his own in a simple, unadorned style that mimics Hemingway’s. What is his influence on your writing today?

I don’t think there is much influence, not on a sentence level. I think what remains from him is putting character first. That’s something that’s central to Hemingway. I think that he handles exoticism really well. I mean, I’ve learned a lot of things from him. He’s part of the DNA. He is not somebody that I look to now, but I used to when I was younger.

Who have you come to look to, which writers are hiding out in this novel?

I think Chekov and Tolstoy would be the dominant ones. Chekov for tenderness, and Tolstoy for his freedom to do weird things. To write a novel without much of a plot. To write a novel where somebody is talking to god. To have a novel where people jump in time decades.

You describe, in an interview with Mohsin Hamid published in Guernica, that Family Life is a modernist novel. Partly because of the risk taking that you just described (the ability to jump in time decades). How else would you describe this as a modernist work?

When I think of what I took from modernist novels, I think of the end of Remembrance of Things Past where Proust says, Oh, I have to go write it all down. That’s the first thing that jumps out. You know, this book has two beginnings and two endings. And the first ending is satisfying. It would be ok to end the book there. The second ending is dissatisfying, it leaves you wondering, ok, what now? And that feels—well that’s life. That these characters are going on without me. In the modernist novels that I think of more often you end the novel and you suddenly think, now the real problem has occurred, has started. Now I have to deal with the real thing. And that’s sort of what I was aiming for.

Do you think there’s something especially interesting about approaching the novel in that way when it comes to depicting what is in part an Indian immigrant story?

This is an immigrant novel. It’s also a coming-of-age story. It’s an illness story. It’s a mother-son, father-son, alcoholic father sort of story. For me, being very aware of traditions, formal traditions, is satisfying, because I think there is a tendency to pigeon-hole. Mostly when people read, they read based on subject matter. And so there’s a tendency to stop—to say, oh this is an immigrant novel or an Indian novel, so we’ll stop at that. Or I will read it as just about an immigrant experience.

Being very aware of traditions is a way of saying, you the reader might think this, but that’s because you’re ignorant. Whereas I know this entire history, and I can tell you the norms in that history and why it is much better than certain things and not as good as other things. You might be ignorant, but I don’t like to spend my time dealing with ignorant people, so I will deal with the writers who made me want to write.

How would you describe the experience of writing this?

For me, I compare this book to my first one. With my first one, I wanted to write a book which people would read and say, this is a good book. And it would be undeniably a good book. What I wanted to do with this book was to be useful. And I’m not totally certain even what I mean by that. I wanted to write a book that somebody could read and feel that you can be brave, whether it’s somebody who’s trying to write a book or someone who is trying to live their life. I wanted to write a book that somebody who is dealing with illness, or has dealt with illness, would read and say, Oh. this is true. We behave very badly, and yet there’s so much love and so much life inside it. I wanted to write about alcoholism, because that’s something that creates such shame within the community. And I wanted to offer the comfort that this occurs, that it’s ok. The motivation felt very different with this book. Here, I was more concerned with presenting people in difficult situations behaving badly and being loved even when they’re behaving badly. The narrator loves them even when they’re behaving badly.

Was Ajay always the narrator?

No, at one point it was a third person narration. At another point the father had a much larger role. At another point the mother had a much larger role. There were 7,000 pages—the equivalent of 35 novels.

What was the process like turning that 7,000 pages into this?

Once I figured out what technique worked, things began to fall into place on its own. What would make a compelling narrative, limiting that sensorium, that was the big change for me.

And that came?

About three years before it ended. Up until then I was flailing. It was horrible. It was really, really the worst thing I’ve ever done. I would never do it again. I wouldn’t. If I knew then what I know now, I wouldn’t have started this book.

What do you think it’ll be like to have it out in the world?

I hope not to find out too much. I think I’m comparing the book with reality. And it doesn’t capture what reality does. Fiction is simple. It’s a schematic thing. You’re trying to encourage readers to do most of the work. I hope to just move on to the next thing. I have a tremendous appetite for pain. I hope not to ever have to satiate that thing. I’m glad it’s done.

What is the next thing?

I’m working on a collection of short stories. I’ve written about eight of them. Several of them I’ve published. And I think I have to write three more beyond these eight.