On the urgency of remembering the fourteen years of Ferdinand E. Marcos, Sr.’s military-backed dictatorship in the Philippines

September 19, 2022

The following editors’ note is part of the notebook Against Forgetting, with art by Neil Doloricon.

“The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.”

—Milan Kundera, The Book of Laughter and Forgetting

When it dawned on us early this summer that 2022 marks the fiftieth anniversary of the imposition of martial law in the Philippines, we at the Asian American Writers’ Workshop felt that we must make space to remember. On September 23, 1972, Ferdinand E. Marcos, Sr., then President of the Philippines, set up a one-man authoritarian regime. As Noel Pangilinan writes in an essay written for this collection, Marcos “abolished Congress, dissolved the vice presidency, canceled the 1973 presidential election, shut down mass media, and jailed critics of his administration, including senators, congressmen, print and broadcast journalists, labor leaders, church leaders, and student activists, among others.”

As coeditors of this notebook, we represent two different generations of people who do remember martial law. We think this is important to note, to refute the all too-pervasive idea that this moment in history has been forgotten or whitewashed. The writers who have so readily contributed to this notebook—themselves representing multiple generations—strengthen our claim. We are among the many Filipinos who have kept the knowledge of martial law alive all this time, despite rampant disinformation campaigns and online troll armies deployed by the dictator’s family. The Marcoses’ propaganda machine is well-oiled, well-funded. It should be. After all, it’s the Filipino people’s $10 billion that they’re using to fund it. But our will to remember is stronger.

For Noel, he saw the face of martial law early on. Its viciousness and repressive nature were unleashed in his working-class, almost lumpen neighborhood in Santa Cruz, Manila. He was still in grade school when he woke up early one morning to the sound of hammers and other metals clashing during a violent showdown between his slum dweller-neighbors defending their homes and a police-backed government demolition squad. The year was 1974—the Philippines was hosting the Miss Universe Pageant—and the government wanted to rid Manila of shanty towns, as part of First Lady Imelda Marcos’ beautification project. Anticipating international attention, Mrs. Marcos wanted to hide these “eyesores.” Thousands of families living in shacks were forcibly removed.

Twice, Noel witnessed a sona, or zoning operation. Sonas, a legacy of the American colonial policing policy of hamletting, were common during martial law. Police troopers would descend on a neighborhood, round up the men, and bring them to the stockade. The men would be kept in detention for up to several days. Noel saw fathers of his friends, and his own uncles and older cousins, made to line up and hauled to a police jail house. The official government line is that sonas were conducted as a dragnet to catch criminals. Later on, however, Noel would come to believe that these police operations were a tactic to flush out community organizers in the neighborhoods.

For Soleil, who was born after the EDSA (Epifanio de los Santos Avenue, named after a labor leader-writer-intellectual) revolution in 1986 that led to the end of Marcos’ twenty-year rule, she has stories, told to her by countless elders, rather than memories. Personal testaments to the brutality and greed of the dictator, the narrowing of civic life for ordinary citizens. Aside from stories, there were the martial law films shown at school, the books about labor leaders killed and imprisoned because they dared stand up to the Marcoses. The famous black-and-white TV newsclip of Ferdinand Marcos, Sr. declaring martial law, ushering in an era of profound state violence. Tens of thousands were tortured and salvaged—the latter word acquiring its meaning of “summary execution” in the context of the Philippines during the martial law era—for the varied “crimes” of being against the dictatorship, being an activist or labor leader, being a journalist, jaywalking, being the relative of a supposed-subversive, or being at the wrong place at the wrong time. Against this backdrop of suppression, the lavishness of the dictators’ lifestyle, the shopping sprees, the famous shoes. Ill-gotten wealth that has yet to make its way back to the Filipino people.

More than just observing a milestone or golden anniversary, we firmly grasped the urgency of remembering those fourteen years of the military-backed dictatorship. A new Marcos administration is now in power in the Philippines, and we share the fears of many Filipinos that Marcos, Jr. and his troll army will not leave a single stone unturned in its frenzy to rehabilitate the older Marcos’ record and image and paint his martial law regime as “the golden age” in the Philippines.

As early as the 2000s, though, the Marcos family had already embarked on an online revisionist project with the single-minded objective of deodorizing the Marcos name. Through Friendster, Flickr, and recently Facebook, YouTube, and TikTok, the Marcos propaganda machine churned disinformation and outright lies aimed at erasing the public’s memories of the Marcoses’ despotism, plunder and economic mismanagement.

Imelda Marcos, one-half of the Marcosian conjugal dictatorship, summed up the guiding ideology of the Marcos family in a 2019 documentary The Kingmaker when she said, “Perception is real, the truth is not.”

Carrying with us a sense of urgency, we quickly reached out to Filipino and Filipino American writers and creatives to contribute works. The response was both swift and heartwarming. Writers and artists are truly the repository of society’s memories. And they proved ready and willing to go to battle for the truth and fight for the people’s collective memory.

Here in this collection, which we’ve called Against Forgetting, are essays, poems, narratives, short stories, and excerpts that tell stories about the nightmare that was martial law.

Noel pens an informative and necessary backgrounder on martial law, serving as an introduction to this dark period.

The writers Joi Barrios, Luis Francia, Eric Gamalinda, Gina Apostol, Sheila Coronel, and Vina Orden share their memories of the era in essays that range from serious to irreverent.

For many people, the Marcos dictatorship was a catalyst to join the underground, as the various human rights abuses, illegal detention, censorship, the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus, and state-sponsored terror forced them into hiding. Ninotchka Rosca, Gato del Bosque, and Alma Domingo give us glimpses of life underground during the era.

An excerpt from Noel’s bachelor’s thesis, translated by Jhong C Delacruz, RN, offers examples and close readings of the poetry written by artist-activists in the underground movement and their effect in strengthening the people’s resolve in their struggle for freedom against the dictatorship.

Three pieces of literature also capture different aspects of martial law: The multi-awarded social realist writer, painter, and artist Jun Cruz Reyes’s 1975 short story “Mula Kay Tandang Iskong Basahan (From Old Man Isko the Ragseller),” translated from Filipino by John Bengan, speaks of the inequality of the time, while Anna Cabe’s “But I Had Always Been A Bad Comrade,” excerpts from a novel-in-progress, brings activist meetings and protests to life. Soleil’s poems (chosen for this collection by The Margins editors) writes martial law as sinister fable, before moving on to describe one of the torture methods of the era, and finally to resistance.

To complement all this written work, we’re also bringing you two songs popularized during martial law, both of which speak to fierce love and loyalty to one’s country, despite oppression.

Mabuhay, Gina Apostol, Joi Barrios, Sheila Coronel, Jhong C Delacruz, RN, Luis Francia, Eric Gamalinda, Ninotchka Rosca, Vina Orden, Gato del Bosque, Alma Domingo, Jun Cruz Reyes, John Bengan, Rene, Cristy, and Marx Rivera, and Anna Cabe!

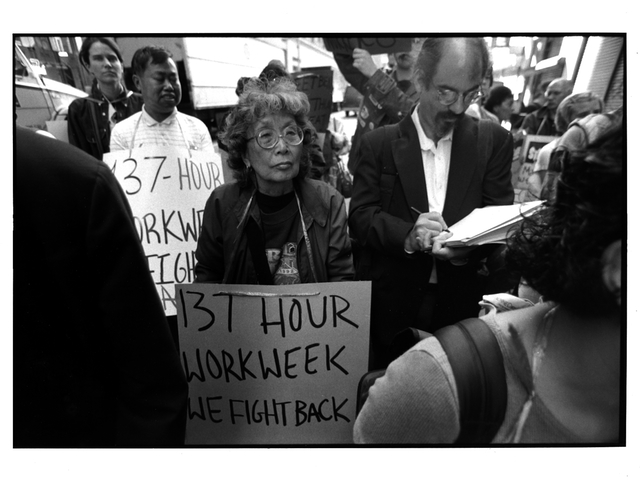

Accompanying each piece in the Against Forgetting notebook is art by the late social realist painter Leonilo “Neil” Doloricon (1957-2021), who championed the working class, the peasant farmers, the underdogs, the revolutionaries, the downtrodden. A truly anti-fascist artist of the people.

Against Forgetting: Martial Law at Fifty is only one of many efforts by Filipinos all over the world to show the dictator’s family that we haven’t forgotten their crimes against the Filipino people. We encourage our readers to explore the various online libraries, films, and commemorative programs that are available. Many more events and actions are planned throughout the week of the martial law anniversary and throughout the year.

Tomorrow, Tuesday, September 20 at 7 p.m. ET, please tune into AAWW’s livestream event Martial Law at 50: To Remember is to Resist. Numerous writers and artists accepted our invitation to share readings. Mabuhay, Vina Orden, Eric Gamalinda, Don Pagusara, Merlinda Bobis, Luisa Igloria, Jun Cruz Reyes, John Bengan, Jill Damatac, Nonilon Queaño, Joi Barrios, Potri Ranka Manis, Bonifacio Ilagan, Nerissa Balce, Candy Gourlay, Victor Manibo, Elaine Castillo, Bino Realuyo, Jessica Hagedorn, Rene Ciria-Cruz, Luis Francia, Cinelle Barnes, Karen Llagas, Albert Samaha, Carla Montemayor, and Alfred Yuson.

Salamat for answering the call. This collection is AAWW’s humble contribution to the overall effort of truth-tellers to fight forgetting and to hold the line when the truth is under siege.