‘In this way, people kept talking about her, and she continued to come to family gatherings. In the eyes of my relatives, she remained a problem that refused to be simplified.’

December 10, 2015

This fall, Indonesia was the guest of honor at the Frankfurt Book Fair, the first time a Southeast Asian nation has been chosen to showcase its literary culture at the world’s largest and most important publishing event. Indonesia’s slogan for this event, “17,000 Islands of Imagination,” evoked the commonplace of Indonesia as “an imagined nation,” and perhaps indicated that even the national organizing committee didn’t know what keeps this country together. Inspired by Frankfurt, AAWW decided it was a perfect occasion to introduce a series on Indonesian literature in The Margins.

Our occasional series, spread out over six months, is designed to showcase some of Indonesia’s most gifted writers and to give readers a taste of an expansive literary tradition that weaves together cultures, histories, religions, languages, and myths. Read an interview with literary translator and co-founder of the Lontar Foundation John McGlynn, an excerpt from Leila S. Chudori‘s novel Home about Indonesian political exiles after 1965, and fiction by Abidah El Khalieqy about a Muslim woman writer taking on the patriarchy of conservative Islam. The following is the fourth installment in our series. Look out for more in The Margins.

Intan Paramaditha is a feminist fiction writer and scholar whose work explores where gender, sexuality, culture, and politics meet. Soon after she published her short story collection Sihir Perempuan (Black Magic Woman) in 2005, Paramaditha found herself being placed into the category of woman writer, a grouping that, although accurate, felt more like a pigeonhole. Indonesian literary history for generations has been mostly the domain of men, and the country’s most prominent literary critics (all men) have systematically diminished the importance of women in literary and intellectual traditions. After the fall of the New Order in 1998, a new generation of women writers arose who, free of the censorship and repression under Suharto, were able to break taboos, writing about sex and sexuality. Alongside them were Muslim women writers who, in their fiction and poetry, charted new ways of being a modern Muslim woman.

While proudly a woman writer, Paramaditha chafes at the expectation that women’s writing be preoccupied with the body, with sex and sexuality. She is wary of being put into any box, and her work subverts many of the walls erected to keep women writers in their own domain. Her writing is inflected with elements of horror, and she counts among her influences Mary Shelley. Another major influence is the work of Toety Heraty, a pioneering feminist writer whose poem about a Balinese sorceress sparked Paramaditha’s desire to write about what she refers to as “bad women in fiction and history.”

One of those “bad women” takes center stage in the short story “Apple and Knife,” translated by Stephen Epstein. The final scene pulls from the Quranic/Biblical story of Yusuf/Joseph, mashing up horror and irony, characteristic of Paramaditha’s interest in twisting and recontextualizing our realities.

Also in The Margins, read an interview with Intan Paramaditha on the political potential of horror and writing as a feminist practice.

—Jyothi Natarajan and Margaret Scott

Apple and Knife

by Intan Paramaditha

Translated by Stephen Epstein

Do you want some?

For ten long seconds, I gazed at her, the past roiling in my thoughts, the present refusing to vanish.

For ten long seconds she dangled the apple right in front of me.

Why that look on your face? She giggled. I’m not going to poison you.

In her face was repeated the tale of the vengeful queen who disguises herself as an old woman to offer her beautiful stepdaughter a poisoned apple. The plump apple glistened, mouth-watering. A killer. Then she asked me if she looked like a witch. I saw her slender, moist fingers. No wrinkles; no blue, bulging veins.

I’ll cut it for you, she said.

She took the decision herself. She did not know that I have never been able to look at an apple without thinking of Cousin Juli. Her ripe apples. Her glinting knife.

The event erupted ten years ago, when I was only seventeen. Cousin Juli was an attractive woman. She had shoulder-length brown hair with bangs that fell sharply on her forehead. At our monthly Quranic recitation meetings she often wore a silk headscarf that would slip down her sleek, straight hair. My mother said she dyed her hair because its natural muted reddishness had begun to be streaked with gray. That could well have been, but there was no denying that she was beautiful. Her round face carried a childlike glow. On her cute lips she wore pink lipstick, applied as delicately as the matching blush. Her small eyes had full lashes, dark with mascara. I felt that she could have passed for a university student.

But Juli was no student. At that point she was thirty-seven years old. She was the wife of Aziz, my oldest cousin. I’d been told that she was a promotions manager for a multinational auto company. Her busy life frequently caused her to get home late and to be absent from our two types of major family gatherings, social clubs and recitations. I didn’t know her that well, but she struck up conversation with me several times. She was the only relative who seemed eager to hear about my plans to major in design. My parents clearly disapproved. They wanted me to enter the Faculty of Economics and work at a bank. In contrast, Cousin Juli increased my enthusiasm for design, telling me about all sorts of work opportunities. When she spoke, I became aware of her wide knowledge and the twinkle of passion in her eyes. I’d scan the animated way she moved. I was attracted to how she applied mascara (she would raise her eyebrows, opening her mouth slightly—at that point I didn’t know the advantage in doing so, but when she did it, I could see her slightly uneven incisors). I was smitten with the lines at the corners of her eyes when she smiled. Smitten with her manicured fingers.

I do not know why Cousin Juli asked me about school so much. Perhaps she was deliberately staving off conversations with the older women. I know they’d pepper her with a variety of questions she did not like. Family gatherings were often an ordeal for her.

“Jul, when are you going to have another baby?” asked Aunt Romlah, my mother’s older sister. “The clock is ticking.”

“I’m still busy looking after Salwa, Auntie,” she replied politely.

“Salwa’s in primary school now. What are you so busy with?” countered Aunt Romlah. “Give her a little brother or sister, so she doesn’t get spoiled.”

“But we both work.”

“Just quit, Jul. Aziz’ business keeps on thriving. What more do you need? You don’t have to run after money.”

Cousin Juli smiled. I noticed that this was her way when she did not want to answer a question. She bowed her head, then flashed an innocent smile like a well-behaved teenager being interrogated by her parents for coming home late at night. Unlike myself at the time, she was no rebel.

Cousin Juli was a magnet for my relatives. She was sweet and enigmatic (or should I say that she was enigmatic because she was sweet?), not taciturn but not inclined to jabber, not challenging but also not submissive. I heard them talk about her at recitations when she did not show up, debating whether she could really read Arabic script. She would only mumble incoherently when we all read the Ya Sin sura of the Qur’an. At social club gatherings, she’d always go home early, unwilling to linger and chat. She thinks she’s too clever for us, Aunt Yati concluded. My aunts commented on her reluctance to help in the kitchen. Look at her smooth fingers and those long pink nails of hers. No housewife has fingers like that. They were gossiping about her at a wedding, when she arrived wearing a tight beige kebaya that left her shoulders bare. I observed her hair, swept up in a high chignon, her long earrings, and the sleekly immaculate nape of her neck. Skin visible behind a see-through brocade. “See, Eva,” Cousin Aziz’ younger sister, Rina, whispered in my ear. “That’s how married women use style to seduce men.”

In this way, people kept talking about her, and she continued to come to family gatherings. In the eyes of my relatives, she remained a problem that refused to be simplified.

Then came the uproar. After talking for two hours on the phone with Aunt Yati, my mother had stunning news to deliver: Cousin Juli would very soon be divorcing Aziz. Word had it that she was caught messing with a young man who was boarding at their house. His name was Yusuf.

As the eldest son, Cousin Aziz inherited his father’s large home. Previously it belonged to my grandfather, a respected Betawi landowner. It consisted of seven rooms but, as usual for a mansion that had survived in the capital, its yard was so small as to look out of balance with the house. Two of the rooms, farthest from the family’s private quarters, were rented out to students or white-collar workers. Yusuf had just come six months earlier. He was twenty-three. After studying at a university in Padang, the young man had begun to travel in search of work. Sometimes he helped with Cousin Aziz’ vegetable distribution business. Even at home he did not hesitate to fix the leaky roof.

“It’s a lesson, Eva,” my mother advised me. “Don’t let schooling ruin your morals.”

For over a month the phone rang without cease. Almost every day my aunts took turns visiting. They never let my mother know in advance, but she would always welcome them. They would chatter in the living room while watching television or at the table while doing the chopping for rujak. I felt that they’d never been this close before. Cousin Juli gave them a sense of shared destiny. Gossip about her continued more freely, to the social gatherings and recitations, because she never showed up again.

“Shameful,” said Aunt Romlah. “Aziz and Juli used to argue because Juli didn’t want to rent out the room. And now look. She lures a guy into her bed.”

That’s what happens when women are too smart, chimed in Aunt Yati.

That’s what happens when women aren’t religious, Aunt Nur added.

And with Aziz she didn’t even have to work. What more did she need?

Maybe she works so she can go on the prowl in her office. Remember that shiny lipstick and those full lashes of hers?

Sometimes I’d think there was nothing new to talk about. Everything was the same old story repeated over and over, stitched together. But Cousin Juli was unquestionably magnetic. You couldn’t ignore her.

Then one day, a bombshell came to my mother over the phone. Not from Aunt Romlah, Aunt Yati, or another relative, but from Cousin Juli herself. My mother’s tone was friendly. I imagine that Cousin Juli was no different. They asked after each other’s news, and then chatted about my cousin who’d just given birth, as if nothing had ever happened. After their call Mom seemed dazed. She looked at me, then without any prompting, said, “Juli invited us next week.”

“A social club?”

My mother shook her head.

“She said it’s a silaturahmi.”

We thronged to her home for this gathering to strengthen ties. It was a strange feeling to know that Cousin Juli had personally invited the women in our large family to such an occasion, inasmuch as anyone could see they had only pretended to get along for all this time. Did Juli know that we were talking about her relationship with that loafer, wondered Aunt Nur. Maybe. But it’s not good to break ties. Anyway, Aunt Romlah said, aren’t you all curious about Yusuf? Whether her young man is in the house? What he’s like?

The man who was fourteen years her junior.

There are indeed thrills to be had in a visit to an enemy kingdom.

Contrary to our expectations, Cousin Juli welcomed us with great warmth. She was wearing a purple dress tailored to follow the curves of her body. I could see strands of white hair at her temples. She was beautiful. Dishes were served buffet style from a long table. My aunts tended to cluster in fixed spots, sitting either in chairs or cross-legged on mats, trying to avoid conversation with the host. Let the old ladies deal with her; we’re only rookies. So said the majority of our contingent. But Cousin Juli came over to each one by turn to chat. The house became a chessboard that pitted them against Cousin Juli, to look for things to talk about, to deftly thrust and parry.

Maybe this is the last time we shall meet, said Cousin Juli when she approached our group: Mom, Aunt Romlah, Cousin Rina, and I. I glanced at the dishes that were almost finished on her plate. Rice, chicken in coconut cream, beef liver in sambal.

We looked at each other. Talk in other groupings died down. For quite a while indeed nobody had mentioned the divorce. Finally Aunt Romlah spoke up, “Don’t let the ties between us be broken, Jul. We are still family.”

Cousin Juli’s lips curled in a smile, and those endearing wrinkles appeared at the corner of her eyes.

The conversation moved on, from the cousin who had given birth to the plans mothers had for their children’s schooling. Absolutely no one was interested in raising the issue of the divorce or infidelity. Then two of Cousin Juli’s maids brought out the dessert. Each guest was given a small plate containing a red apple and a sharply whetted knife. I felt that something odd was going on, because sweets are usually available at the table from the start.

Cousin Juli apologized for the inelegant dessert, then talked about her diet. She had wanted to make a chocolate cream pie, but according to the doctors, her cholesterol was becoming a concern.

“Surely not. You aren’t at all fat,” said Cousin Rina. “Anyway, apples are fine.”

“Apples truly are tasty,” Cousin Juli fondled her apple, as if talking to herself. She grabbed a knife and began to peel.

The women around her exchanged glances, but out of respect for their hostess they too began to take their knives to their own apples. I saw Cousin Juli whisper something to her maid. The young girl nodded and left the room.

I studied the apple of Cousin Juli in front of me. Red, round and ripe. The sharp glittering blade offered a reflection. Was that my face? I thought I could see Cousin Juli there. Something crept into the gleaming corner of her eyes, looming in the furrows of her forehead that appeared when she smiled, and revealed uneven teeth. Children’s teeth with bicuspids that were too long. Sweet aging lines.

As the women were busy slicing their apples, I heard Cousin Juli say, “Let me introduce you to Yusuf.”

Her voice sounded so calm.

Soon all heads turned toward a figure entering the dining room with careful steps. Finally I saw the object of the attention. His youth stood out so in this room filled with middle-aged matrons. His body was tall, his shoulders straight, his arms sturdy. He wore a short-sleeved shirt that showed off his gleaming chocolate flesh. His eyebrows were as jet black as his piercing eyes. At that time for me he was not so different from friends my age who were idolized by girls. He was too simple, but he radiated child-like appeal. Whether it was his wild, curly hair or his strong cheekbones or his full lips, something invited delicate fingers to trace along them.

Yusuf.

There was a pause. Time stopped as the women held their breath and stared at the young man. They did not blink; their hands did not release their knives. Suddenly I heard faint sounds from their lips. Poignant groans as fingers continued peeling. The tough skin of red apples that had passed the point of ripeness. Was that apple? I caught another scent. An ancient, intoxicating aroma. Blood flowed from my aunties’ palms, wetting the knives, wetting the apples, staining the tablecloths. Chunks of apples were cast to the floor. Drops of fresh blood seeped straight out and turned dark. Cousin Juli’s knives had been readied, but not to pierce the flesh of apples.

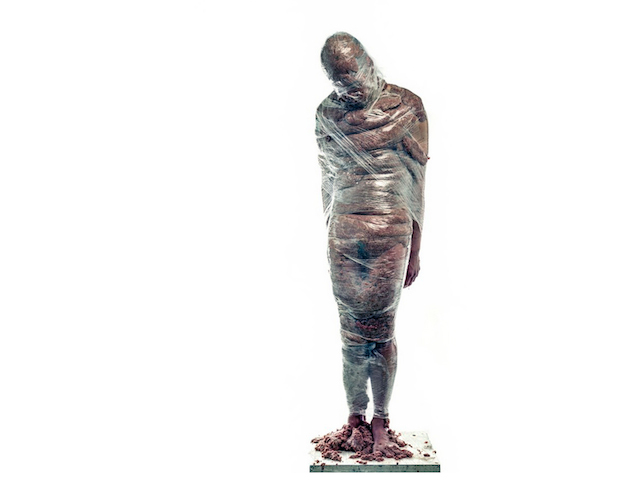

Yusuf bowed, pale. The staring of the women made him uneasy. The youth was like a trembling angel. His torn wings were skewered by the gaze of the women who were carried away in the maelstrom. Soon he fell. Birds of prey crowded about in attendance upon a queen. Cousin Juli, the woman behind the play of apples and knives, observed her victims, still under the spell of their own passion, a passion that had stolen in amidst blood and pain. Eventually everything became blurred; you no longer knew who was victim, who was tormenter, who enjoyed pleasure, who suffered pain. You realized that they willfully scratched deeper, gouging their lust. The women had come together in Cousin Juli’s spider web, enveloped in an aroma of meat and fruit, so fresh. She gave a winsome smile. She glanced at the chocolate angel, then her eyes turned toward me. I felt fragile, and soon fell.

Your wings are torn, let me patch them. Like the way I patch my ties with others.

Slowly, so slowly, Juli licked her lips.

Ouch!

She had hurt herself, cutting the apple carelessly. Was this involuntary manslaughter, or a premeditated act? My apple. I approached her.

Does it hurt?

She closed her eyes, without answering.

Let me see.

She held out a bleeding hand. I took hold of her long, tapering digits. Her fingers brought back memories of Cousin Juli. Succulent, smooth, nails painted pink. We stood so close, the apple cutter and I. Her bangs fell on her forehead, strand by strand leading fingers astray.

My breathing gets rough when I see the color red. A fragrance so intimate, reminding me of beginnings, suddenly tickled my nose. My mouth watered, but not because of the apple.

Slowly, so slowly, I licked the wound on her finger.