‘When the Japanese were in power, I realized that the Dutch East Indies with all of its aristocratic ways, was finished. I must have the guts to say goodbye to it. And whatever fate befalls me, I will remain here.’

January 29, 2016

The following is the fifth in a series on Indonesian literature in translation. Scroll down to read more about the series.

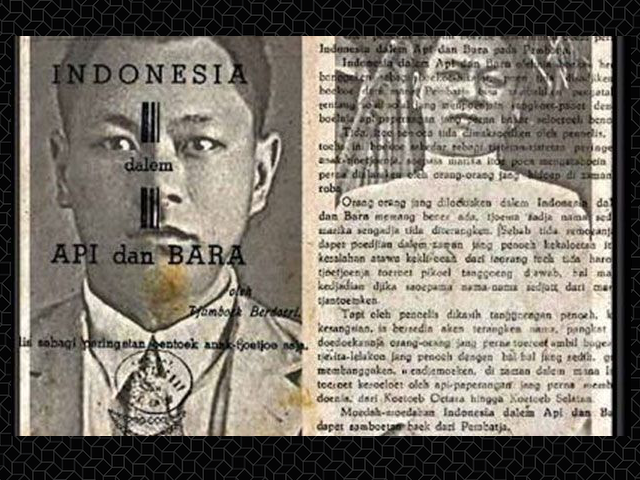

On August 17, 1945, almost immediately after the Japanese surrender in World War II, Indonesians embarked on another war—for independence. Indonesian freedom fighters declared their liberation from more than 100 years of Dutch colonial rule that day, but when the Dutch refused to accept their demands, four bloody years of struggle followed.

The history of the fight for independence is complicated, and much of it lost or forgotten, since history in Indonesia, like in many places, often became the servant of a national project. Under the flamboyant revolutionary-turned-autocrat Sukarno, and later, under the jackboot rule of General Suharto, history was controlled and often amounted to propaganda. In the case of the independence struggle, Indonesians have been taught that freedom fighters bravely vanquished the Dutch, the end. For decades, the history taught in schools erased the darker periods in Indonesia’s past.

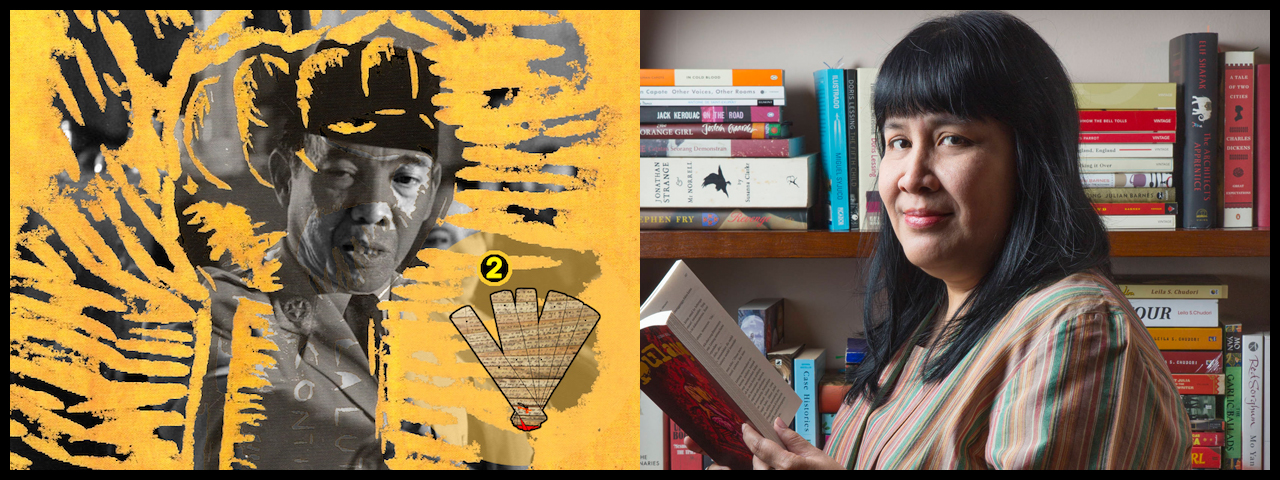

Since the fall of Suharto in 1998, many Indonesian writers looked to these forgotten or distorted histories as the source of literature. A generation of writers began to excavate the brutal violence of 1965, during which nearly one million alleged communists were massacred. Meanwhile, writers like Iksaka Banu have reached back further, to the Dutch colonial period and the war for independence, to imagine the lives of ordinary people living in the East Indies and to insist that they, too, are part of Indonesia’s story.

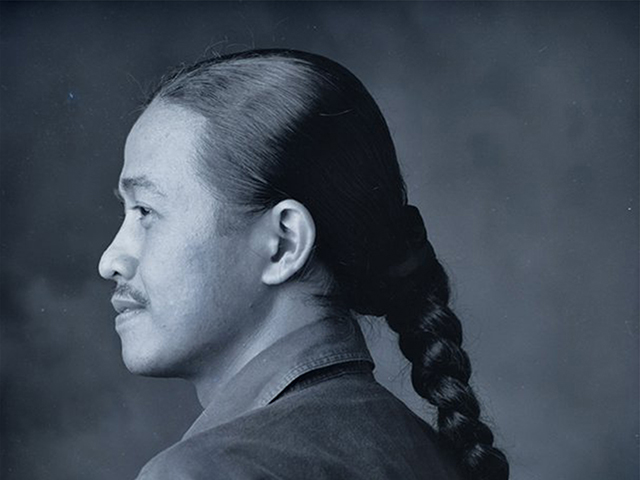

Iksaka Banu’s historical fiction is revelatory. His stories overturn the narratives that millions of Indonesians have grown up learning. As the critic Kendisan Kusumaatmadja wrotein Tempo, Banu’s work “concerns itself with the particulars of history that tend to elude history books, spaces retrievable only through invention.”

In “Farewell to Hindia,” published in the short story collection A Shooting Star and Other Stories by BTW Books (2015) and translated by Tjandra Kerton, Banu turns to a moment in 1945, when Indonesia is perched between two wars. The Japanese have surrendered and are forced to end their occupation of what was then the Dutch East Indies. Banu places the Dutch, the Indos (the term used to refer to mixed race Dutch Indonesians), and the Chinese back into the narrative, and bits of history that are surprising even to many Indonesians rise to the surface. The Japanese occupiers kept Dutch civilians in internment camps during the war; the Japanese armed Indonesian freedom fighters against their colonizers; and the Dutch, returning after the war, called in British forces—made up mostly of Indian troops—to help them regain control of Indonesia. Blood was on everyone’s hands, with vengeful mass killing feeding vengeful retaliation.

“Farewell to Hindia” focuses on a Dutch journalist’s struggle to make sense of the violence, including the little-known slaughter by supposed freedom fighters of emaciated Dutch civilians as they were tossed out of internment camps. The protagonist questions where his loyalty lies as the war ends and the fate of the East Indies is unknown. Deeply researched and humane, Banu’s work revives history and rejects propaganda.

—Jyothi Natarajan and Margaret Scott

Farwell to Hindia

by Iksaka Banu

Translated by Tjandra Kerton

The old Chevrolet that I was riding in slowed down, before finally stopping in front of the bamboo barricade that had been erected across the end of Noordwijk Street. Soon after, like a nightmare, from the left of the building appeared several long-haired men wearing red and white bandannas and dressed in a variety of shabby uniforms, brandishing weapons.

“Local militia,” murmured Dullah, my driver.

“Make sure they see my press identification,” I whispered.

Dullah pointed to a piece of paper on the car’s windshield. One of the men peered in through a window.

“Where are you going?” he asked.

He was wearing a black peci.

His bushy mustache split his face in two.

He glared threateningly at us.

“Merdeka, Sir! We are going to Gunung Sahari. This is a journalist. He is a good man,” Dullah said, trying to keep a calm face, pointing his thumb at me.

“Get out of the car, then talk, damn you!” Mr. Mustache barked, slamming his fist against the bonnet of the car.

“Make the foreigner get out too!”

Hastily Dullah and I did as he said. Assisted by some of his friends, the Mustache searched us thoroughly. My Davros cigarette pack from which I had been enjoying a cigarette was immediately transferred to his shirt pocket and the same went for several Japanese military banknotes in my pocket. Another thug climbed into the car, searched through the glove compartment then sat in the driver’s seat, spinning the steering wheel like a child.

“Martinus Witkerk. De Telegraaf,” Mr. Mustache intoned, reading my assignment letter, then looked at me.

“You Dutch?”

“He cannot speak Malay, he’s from Holland,” Dullah interjected.

Of course he was lying.

“I’m asking him, not you, dammit!” the commander struck Dullah across the face. “Your friends have died from their bullets, yet you befriend the colonials. Get outta here, go home!” he returned my wallet as he lit up one of his stolen cigarettes.

“Thank you, Dullah,” I said a few moments after we had started on our trip again.

“Are you ok?”

“I’m ok, Sir. That’s what some of them are like. They say they’re freedom fighters, but they invade people’s homes, asking for food or money. They also frequently harass the women,” Dullah replied, “Lucky I was the one driving. If Mr. Schurck had been driving, I think that neither of you would have been safe. They tend to kill Europeans who are quick to anger, like Mr. Schurck. It doesn’t matter to them if you are journalists.”

“One thing’s for sure, Jan Schurck is good at getting himself into dangerous situations,” I said, smiling, “That’s why Life pays him so well.”

“Are you sure of this young lady’s address?”

“Yes, across from the Topography Office. She doesn’t want to leave. Miss Stubborn.”

Stubborn.

Maria Geertruida Welwillend.

“Geertje”.

Yes, that’s what people called her.

I had met this woman in the Struiswijk internment camp, not long after the official announcement of Japan’s surrender to the Allies.

At that time, several journalist colleagues and I were discussing the social impact of Japan’s defeat on the Indies at the Hotel Des Indes, which had been returned to Dutch management.

“The Proclamation of Independence and the collapse of the local authorities have made the indigenous youth forget the line between ‘freedom fighter’ and ‘acting in a criminal manner’. Long festering hatreds towards white-skinned people and those who were considered collaborators with the enemy suddenly seemed to find their outlet on empty streets, in the residential areas of Europeans that bordered directly onto villages,” said Jan Schurck, throwing a photo down on a table.

“God almighty. These bodies are like minced meat,” exclaimed Hermanus Schrijven from Utrechts Nieuwsblad, making the sign of the cross after he’d looked at the photos, “I heard that these butchers are the villages’ so-called champions or thieves who had been recruited into the army. Some of the spoils were divided up amongst the community. But they took a lot themselves.”

“Patriotic bandits,” said Jan, shrugging his shoulders, “It happened during the time of the French Revolution, the Bolshevik Revolution, and it’s still happening among the partisans in Yugoslavia today.”

“Illegitimate children of the revolution,” I replied.

“I hate war,” said Hermanus, throwing away his cigarette butt.

“The European community does not realize the dangers,” I said, “After suffering for a long time in the camps, they wanted nothing else but to go home. They don’t know that their servants have been transformed into freedom fighters.”

“I think many of them didn’t hear the message from Lord Mountbatten to stay in the camps till the Allied forces arrive,” said Eddy Taylor from The Manchester Guardian.

“You’re right. And the Japanese commanders, who don’t have the will to live after their defeat, are inclined to let their prisoners leave. It’s worrisome,” said Jan lighting yet another cigarette.

“It could get worse. On 15 September, the British forces arrived in Batavia Bay,” I said, pointing to a map on the table, “A Dutch cruiser that was accompanying the landing has caused considerable consternation among the militants. This seems to strengthen their assumption that Holland will return to the Indies.”

“Well, just between these four walls, do you think that Holland intends to return?”

Eddy Taylor looked from Jan to me, and back again.

The discussion was suddenly interrupted by a cry from Andrew Waller, a reporter with the Sydney Morning Herald who had been closely following developments on the radio.

“Interesting! This is interesting! Dutch and British soldiers moved the occupants of the Cideng and Struiswijk camps this morning.”

Without further ado, we all hastened to leave. Jan and I chose to visit the Struiswijk Internment Camp.

Major Adachi, the Japanese commander whom we met there, was pleased at this mass evacuation.

“Our patrols have been seeing the bodies of Europeans who fled from the camps. Smashed to bits inside sacks on the side of the road,” he said.

I nodded as I made notes, but my eyes were actually drawn to Geertje who was walking leisurely along carrying a suitcase. She was not going towards the trucks, but towards Drukkerijweg Street, preparing to get into a becak.

“Hey, Martin!” called Jan Schruck, “That girl has been eyeing you for a while now. Don’t squander your chances. Go after her!”

I did go after her, but got a shocking surprise.

“I’m not going,” said Geertje, looking at me sharply. “These trucks are going to Bandung. To a shelter at the Ursuline Chapel. Some are going to Tanjung Priok. I must go home to Gunung Sahari. There is so much I have to do,” she said.

“You mean to say that before the Japanese came, you lived on Gunung Sahari, and now you wish to go back there?” I asked.

“Is there something wrong with that?” Geertje asked.

“Yes, there is. The wrong time and the wrong place. More and more whites, Chinese and those considered collaborators with the Dutch are being murdered. Why are you going there?”

“Because that is where my home is. Excuse me,” said Geertje, turning her back on me, and picking up her suitcase once again.

I was stunned. From afar I could see that bastard Jan give a thumbs down.

“Wait!” I ran after Geertje. “Let me take you there.”

This time Geertje did not refuse. And I was grateful that Jan was willing to lend us his motorcycle.

“Be careful with this young lad, Madame,” said Jan, winking. “In Holland many unfortunate women are waiting for him to return.”

“Is that so? Call me ‘miss,’ or just my name,” Geertje responded.

“Oh, in that case call me Jan.”

“And I’m Martin,” I said, slapping my chest.

“Don’t you want to get rid of those wooden camp clogs?” I asked, eyeing Geertje’s feet, “Didn’t the soldiers provide shoes for the women and children? They also gave out lipstick and powder. You’ll all be beautiful again.”

“I’m not used to wearing shoes, so I’m keeping them in my suitcase. At the camp, I got to be really good at running in clogs,” Geertje explained with a laugh settling herself behind me on motorcycle.

My God.

That husky laugh, those dimples.

What an odd combination with her severely plucked eyebrows.

A face of mystery.

Did this woman have a family? A husband?

But she had asked to be called ‘miss’.

“Battalion X often passes through Gunung Sahari. They’re guarding the European residences, but of course no one knows when there will be an attack. Do think about my suggestion?”

I looked at Geertje in the rear view mirror.

She appeared to want to say something, but Jan’s motorcycle was extremely noisy. In the end both of us were silent for the rest of the journey.

At the Kwitang crossroads I turned right, leaving the line of trucks with their load of women and children behind me.

Oh, those children.

Boisterously clapping, singing happy songs. Not realizing that the land of the Indies, the place where they were born, would most likely soon be just a memory.

“In front of that pond,” said Geertje, waving.

I turned.

The large house was in a pathetic state.

Dirty wall.

Broken window glass scattered here and there.

The strange thing was, the grass in the yard seemed to have recently been cut.

“Wait a moment!” I said grasping Geertje’s arm when she attempted to run to the terrace. From my bag on the back of the motorcycle I took out a stiletto knife that I had borrowed from Jan. I pushed at the front door.

It was locked.

“Do you still want to go in?” I asked.

“Yes,” Geertje replied, “Put away your knife. Let me knock. I hope the house hasn’t been taken over by another European family.”

“Or by the militia,” I responded.

Geertje knocked several times.

There was no answer.

We went around the back. The back door was slightly open. We were about to go in, when we heard footsteps coming from the garden. Coming towards us was an Indonesian woman. Fifty years old maybe.

“Miss!” the woman cried, hugging Geertje’s feet.

Geertje pulled at the woman’s shoulders to get her to stand.

“Japan has been defeated. I am home, Iyah. Where is your husband? Have you been living here?” Geertje asked, “This is Mr. Witkerk, my friend. Martin, this is Iyah. My housekeeper.”

Iyah bowed to me, then turned back to look at Geertje.

“After I came to see you the last time, the house was taken over by the Japanese. It was made into a residence for the officers. I cooked for them. I could not leave. That is why I could not visit you,” Iyah broke into tears again, “Where are your father, your mother, and young Robert?”

“Mother died last month, from cholera,” said Geertje, pushing the door open wider, and then going inside. Iyah and I followed. “Father and Robert were sent to Burma. I’ve asked the camp commander to search for news of them,” she continued.

“Everything of value was taken. The photos on the walls are all gone. They were replaced by the Japanese flag. But not too long ago they left in a hurry. I don’t know where they went. They left many of their belongings behind,” Iyah said, “I took the cooking utensils in the store room and asked my husband to come. After becoming the cook, I had moved to the storeroom in the back yard. After they left, I didn’t dare stay on. But I come and do what I can to keep the place clean every chance I get.”

“Ask your husband to come. We can rebuild this house. When the banks are open again, maybe I can take out some of my savings,” Geertje let Iyah run outside, and then continued with her inspection of the house.

Some tables and chairs as well as cabinets remained, though they had been emptied of their contents. There was a surprise in the family room: an elegant black piano. It was most surprising that the Japanese had not taken it, or damaged it. Perhaps they had used it for entertainment.

Geertje blew away a thin layer of dust, opened the keyboard cover. A joyful blend of notes filled the room.

“A folk song?” I asked.

Geertje nodded, “Si Patoka’an.”

She started playing.

“You seem one with nature and the people here. They like you too. And their love for you may be pure and genuine,” I said, “But the era of the servants will soon be over. America is increasingly showing their dislike for colonialism. The outside world is also monitoring every beat of change taking place here. And our presence for more than three hundred years as the ruler of this country, some might say eating the heart of this country, is worsening our bargaining position. I don’t think the Dutch East Indies will ever return, however hard we try to take it back from the indigenous nationalists.”

“Once the fires of revolution have started, no one can stop them,” said Geertje, the piano keys now silent under her fingers, “They just want to be independent, as my father would say. My father was an admirer of Sneevlit. He was prepared to forsake his special rights here. I was a teacher of the indigenous students. I was born and raised amongst the indigenous people. When the Japanese were in power, I realized that the Dutch East Indies with all of its aristocratic ways, was finished. I must have the guts to say goodbye to it. And whatever fate befalls me, I will remain here. Not as ‘one in power,’ to use your term. I don’t know as what. The Japanese taught us a lesson, how awful it is to be a servant. After living prosperously, wouldn’t it be shameful for us to run away at a time when these people need our guidance?”

“These people…” I could not go on.

There was silence for a few minutes.

“There was once a hunter who found a baby tiger,” I finally let out a sigh, “The animal was taken care of lovingly. It became tame. It ate and slept with the hunter till it was grown. It was never fed meat. One day, the hunter scratched his hand on a the tiger’s tin plate. Blood flowed from the wound.”

“The tiger licked the blood, became wild, and then attacked the hunter,” said Geertje, interrupting. “You’re trying to say that at some point the indigenous people will stab me from behind, right?”

“We are in the midst of a huge worldwide upheaval. Values are being pushed aside. After centuries, we realize that this land is not our Motherland,” I replied, “I ask for the third time, please go while you still can.”

“To Holland?” Geertje closed the piano, “I don’t even know where that is, the land of my ancestors.”

“In my village in Zundert, there are some reasonably priced rental houses. You can stay there while you wait for news of your father.”

“Thank you,” Geertje smiled, “You know where I wish to live.”

That had been Geertje’s response several months ago.

I did meet her twice more. I put some windows in, and I took her to market. After that, I became heavily involved in work. Geertje was also focused totally on rebuilding her house. It was difficult to imagine any spark of love between us.

Then the news came that there had been a violent battle last night, that spread from Meester Cornelis to Kramat. Several paramilitary youth groups staged major attacks on a number of areas in an organized and planned manner. A Dutch tank had even been taken over in the vicinity of Senen-Gunung Sahari.

I was worried about Geertje. I should really just go and get her. Have her stay with us for a while. Hopefully she would not refuse.

Schurck happened to be out of town so I couldn’t borrow his motorcycle. Luckily, although it was rather expensive, I was able to rent a car and driver from the hotel.

“Out the front, Sir?” Dullah’s voice brought me back to the hot cabin of the Chevrolet.

“Yes. Wait here,” I said, jumping out of the car anxiously.

In front of Geertje’s house, several Dutch soldiers were standing on full alert. Others were milling around in the back yard. The veranda of the house was damaged. The front door had collapsed, riddled with bullets. The flooring and walls were torn up, blackened, the result of a grenade explosion.

“Excuse me, I’m a journalist!” I said as I pushed through the crowd, holding my press card. My eyes flew everywhere. I went into every room, a mass of mixed emotions, expecting to see Geertje’s body lying in a pool of blood on the floor. But that terrible sight did not ensue. A soldier approached me. He seemed to be the commander. I showed my press card.

“What happened, Sergeant…Zwart?” I asked, glancing at his name on his chest, “Was the house a target of last night’s attack? Where are the occupants?”

“It was us who attacked. The occupants have fled. You’re a journalist? What a coincidence. We intend to spread the word, so that everyone is on the alert,” Sergeant Zwart said, leading me to the kitchen, “This is where the rebels were gathering. We found a lot of anti-Dutch propaganda material.”

“Sorry,” I broke in. “As far as I know this house belongs to Miss Geertje, a Dutch citizen.”

“You know her? We will be asking a lot of questions. There is a suspicion that Miss Geertje, alias the ‘Emerald of the Equator’ alias ‘Motherland’, names that we’ve often heard over the illegal air waves recently, has switched sides.”

Geertje?

I stood open-mouthed, ready to protest, but Sergeant Zwart was too busy pulling open a large trapdoor near the storeroom.

A bunker.

It had escaped my attention when I had visited Geertje some time ago.

I followed the Sergeant down the steps.

There was nothing odd about it. Sensible Dutch families usually had a room such as this. It was a place to shelter when there were air raids at the beginning of the war. A damp room, about four meters square. There was a long table, chairs and a dilapidated cabinet filled with tableware and piles of paper. Papers that were indeed anti-Dutch propaganda material.

Sergeant Zwart unwrapped an object hidden by a veil behind the cabinet.

A radio transmitter!

“Something left over from the Japanese,” the Sergeant said.

I was struck dumb. It was difficult to believe all of this, but what made me really go cold was what I saw on the weathered lefthand wall, where a sink and mirror hung. There was writing on the mirror. It had been hurriedly scrawled, using lipstick:

‘Farewell to the Indies. Welcome, the Republic of Indonesia.’

I saw in my mind’s eye Geertje and her dimples, sitting in the ricefield, singing along with the people she loved:

“This is my land. This is my home. Whatever fate befalls me, I will remain here.”

From the beginning Geertje knew where she would stand. Slowly I came to terms with this fact and the word ‘traitor’ disappeared from my mind.

With support from the Lontar Foundation and the New York Southeast Asia Network (NYSEAN), the Asian American Writers’ Workshop has been publishing a series on Indonesian literature in The Margins. Read more from the series below.

In August 2015 we kicked off the series with an interview with John McGlynn, a co-founder of Lontar and a celebrated translator of Indonesian literature.

In September 2015, in time for the 50th anniversary of one of the worst massacres in the 20th century, we featured the work of journalist and novelist Leila Chudori, whose novel Pulang, or Home, published in October by Deep Vellum Press and translated by John McGlynn, fictionalizes the story of two generations of Indonesians whose lives were transformed by the events in 1965 and the fall of Suharto in 1998.

In our third installment, we featured an excerpt from Abidah El Khalieqy‘s 2012 novel, Mataraisa, or Eye of Raisa, translated by Joan Suyenaga. El Khalieqy’s novels and short stories delve into the often clashing—sometimes violently—versions of what it means to be a Muslim in Indonesia.

Most recently, we featured the short story “Apple and Knife” by Intan Paramaditha, a feminist fiction writer and scholar whose work explores where gender, sexuality, culture, and politics meet. Translated by Stephen Epstein, “Apple and Knife” adapts the Quranic/Biblical story of Yusuf/Joseph and Zulaikha, mashing up horror and irony.