“Show up and that’s enough, and you can leave all this neurosis behind.”

November 12, 2021

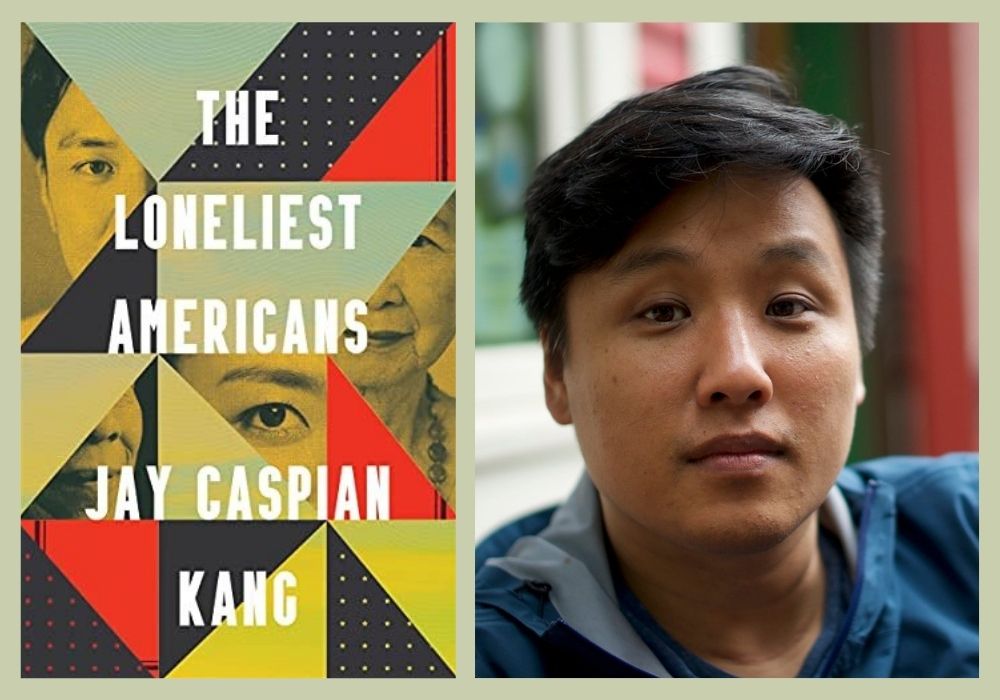

I don’t remember when I first began reading Jay Caspian Kang’s writing. I do know it had to be no later than 2017, as he and I had a phone meeting about Asian American activism as he was finishing up his New York Times Magazine feature that would be published that year. That story, “What a Fraternity Hazing Death Revealed About the Painful Search for an Asian-American Identity,” provides both the thesis and title for Kang’s second book, The Loneliest Americans, published in October of 2021. During the four years between these two publications, I read a lot of Kang’s writings, from his tweets to his stories and opinion pieces. I found in his work someone who takes seriously both the craft of writing and interrogating Asian American identity and politics. Many times I felt his writing to be simultaneously beautiful, funny, and frustrating. Owing to the beauty of the writing, as well as Kang’s humor, I have to dig deeper for what bothers me in what he’s saying—which pushes me to clarify my own thinking, a reading experience I kind of enjoy. Reading The Loneliest Americans was no different. Kang’s conceptualization of loneliness as a sociological framing of Asian America’s position in race politics, both ascribed and chosen, is provocative and ties together what Kang has been hinting at, sometimes loudly, in various places about how Asian Americans practice and narrate our political identities.

While we covered several topics in the two hours we met for this interview, a significant amount of time was given to exploring the debate among some Asian American scholars and activists regarding Kang’s skepticism about a coherent Asian American identity and his consideration of Asian Americans and coalition politics. As discussed in our interview, what some might read as Kang ignoring the history of Black-Asian solidarity is actually him interrogating it. In the process, The Loneliest Americans raises controversial questions about the performance and reality of Asian American politics against the backdrop of shifting Asian American demographics following the 1965 Immigration Act, as well as the contemporary social justice landscape in which discourses of solidarity, allies, and privilege commonly circulate.

This interview was conducted with Jay Caspian Kang on October 22, 2021, via Zoom. It was edited for length and clarity.

Tamara K. Nopper

One of the critiques you’ve gotten is that you’re not saying a certain narrative about doing Asian American politics or solidarity that some might want to hear you say.

Jay Caspian Kang

Well, everyone has an opinion on what this book should have been. And a lot of the criticism is, “Why didn’t you talk about X?” And I don’t feel any responsibility to X, because why would I? I think that leads to the same book being published over and over and over again.… People can hate the book, it’s fine, but to ask, “Why is it that you haven’t done the thing that I care about?”—that places so much pressure on individual writers. And I don’t quite get why so much pressure is placed on all our work—this idea that there’s nobody writing about Asian Americans right now, or that there are no Asian American writers, it’s just nonsense.

TKN

There’s been this idea that The Loneliest Americans is centering whiteness or that you as an author have self-hatred. And in your book you use the word neuroses several times to describe your own exploration into Asian American identity. Was there anything about sharing that that scared you or worried you?

JCK

No. No, no, not at all. Because I think if you’re going to be a writer, you should be very honest. And you should try and fulfill the people before you whose writing you admire and really touched people. What’s the point of doing it otherwise?

I think we all have moments of deep self-hatred and feeling terrible about ourselves. That doesn’t mean that people are like, “Hey, I wish I was white, I wish my hair was blonde, and I wish I had blue eyes.” But this idea that we can’t talk about our self-hatred because it’s embarrassing and makes us look bad or strange to white people—I find that so odd because then you’re basically just being like, “Well, I’m only out here for white people, that I care so deeply about what white people think that I’m just going to lie to you. I’m not going to just lie to my readers and shortchange them, I’m also going to lie to other Asian people,”—that’s the idea. Because we all know there is an element of self-hatred that goes into being raced—it’s one of the effects of living under white supremacy. If that’s true, then of course it has psychological effects on us. We’re all trying to get through it. I’ve always had that outlook on Asian, Asian American people—I find it very difficult to judge any of them…. When people say [you have self-hatred], I don’t know. I feel like it is a very odd thing to make fun of someone for being sort of psychologically damaged and for carrying that with them throughout their life. I just don’t believe the people who are doing it don’t struggle with this [as well], I don’t believe that you’ve fully decolonized your mind, or whatever.

TKN

You make this argument in your book with regard to how people have constructed an understanding of Asian Americans and racism, and the symbols and history they draw from to situate themselves in racial politics. You make this provocative argument that post-1965 immigrants don’t totally relate to that history and those symbols, and you also look at their attempts to relate to it and be interpreted or plugged in, through contemporary social justice narratives of what it means to do “good” Asian American politics. And I think that’s where the storyline of your narrative pisses people off. Whereas if you had talked about neuroses, but then the so-called resolution or clarity that you got was, we should all be doing this version of social justice/Asian American/solidarity politics or being part of POC coalitions, I think that would have been more acceptable to some people. With your concept “loneliest Americans,” you reject the idea that Asian Americans want to be white, but you also make a really provocative statement about locating an authentic place for Asian Americans in coalition politics, or what is seen as the so-called correct social justice path for Asian Americans. And you don’t take that path and you don’t demand that other Asian Americans take that path, and I think that is why some people hate what they think your book is about.

JCK

…the moment that’s upheld as this great moment of solidarity and possibility within Asian America—Asian Americans care about this moment more than anyone else—is the Third World Liberation Front. It is seen as this example of when we did what we actually can do, and that if we use this as a model for inspiration, then we can find solidarity with other people. There’s a lot that I admire greatly about the people who organized the Asian American Political Alliance (AAPA) and Third World. I think this idea that they had at the beginning—that we will organize everyone who isn’t organized, we’ll let in everyone who’s not in another group, and that’s what we are—I think is beautiful. Like I genuinely think it’s a beautiful idea.

But I think that we have to understand that that impulse comes out of a sense of rejection, too. Like Vicci Wong who tried to join the Panthers. When they told her to go do something else, do your own thing, that’s when she joined AAPA…. My point here is that I do understand why people are attached to the story. But I think that we have to be realistic about who those people were and why they were able to situate themselves in politics that way. The other people who were in AAPA at the time, their families had been in California for five generations. They were living under the era of Chinese exclusion… They could situate themselves very clearly under a rubric of white supremacy and it made sense to them. I don’t think that post-1965 babies are quite there yet. I think that we understand microaggressions, I think that many of us do understand violence in a type of way, but we have not actually articulated our own version of that. And my proof that we haven’t articulated our own version of that is because when we try and articulate a version of that, we talk about the Third World Liberation Front. We don’t have our own thing, we just go right back to the old thing. And so, yeah, I think that that is a lonely position. I think that is an alienated position. I am not saying this out of scorn or sarcasm or out of contempt for people who attempt to do that. I’m saying, out of sympathy, it is sad that we don’t have this, it is bad that we don’t have this, and I wish personally we had it, too. But we just don’t, and we just have to be honest about it.

TKN

To me, your book has a much more tender argument about what it means to be the loneliest Americans. And I think what’s happened is that some people see you as kind of shitting on the things that they care about and that they fought really hard to get into public consciousness around these political struggles. I actually see you making a much more complicated kind of argument than even what I think you do publicly, or when you make these sound bites.

JCK

I understand that there’s a fair perception of me as being a bit of a cynic. And, you know, I think that I probably deserve that just because of my presence on social media. None of these people actually know me, so it’d have to be through social media. But I’ve always felt that my writing tries its best to be as deeply sympathetic towards its subjects as possible, sometimes to people’s actual annoyance. Like, “Why does this person seem so interested in what these toxic frat bros who killed a kid think? Why does he feel sympathetic towards them?” That’s just what I think writing is.

I think the misconception is that when I write about how I saw two kids at a protest last summer holding a “Yellow Peril Supports Black Power” sign, that I think that they are idiots and that I’m sneering at them. It’s the exact opposite of that, and that misconception really pisses me off because it thinks so little of the person who is writing that passage and makes such large assumptions about who that person is. My thoughts about those kids who I saw is one of deep sympathy because I’ve been in that position, too. I went to protests when I was a kid. I felt so nervous because I was just one of three Asian people or zero Asian people at this protest. I’m the only one, you know—how do I situate myself here? It’s just white allies and Black people, or if it’s an anti-war protest, it’s just a lot of white people. You feel nervous about it, you want to do something. Either you want to sort of abandon your identity and you want to be part of the crowd that’s part of the protest, or you want to say, “Hey, I’m here too, I’m a representative of my people.” Then what is the language that you can bring to that second action. Well, it’s a lot of nostalgic stuff like those two kids do. And that’s why they end up in that place where they’re holding that sign. There’s nothing wrong with it. It’s just that I understand that that’s how they got to that place and that there’s a stranglehold on them of anxiety and neurosis about it, and I sympathize with them. I want them to have something that’s better, something that they can fully occupy. And so to say that that’s sneering at them is to fundamentally misunderstand the book.

TKN

You didn’t say this so much in your book but you say it in interviews, that if we try as Asian Americans to depict our politics as always about social justice and in solidarity, we’re not always dealing with all these Asian Americans we don’t want to deal with. And in your book you talk about all these examples of politics, examples of Asian Americans who don’t think they’re white, who have grievances, they’re organizing in various ways, some ways you are critical of and find harmful, but you’re saying they’re all doing it with the sensibility of being outsiders and not white, but that we don’t always deal with them. We like to kind of almost hide them because it doesn’t work well for us being seen as good coalition partners in solidarity work.

JCK

But I always want to know: What is that solidarity work? What is the coalitional work? Who are the people who really think that an Asian American respectability needs to be obtained so that they can continue to do the so-called work that they’re doing?

I’ve been looking at this for 10 years now, and what I have found is that there are people who are deeply invested in that type of coalitional work, people who are deeply invested in the lives of immigrants, people who are living in great precarity, and undocumented people. Not many of those people sit on Twitter all day [worrying about] how this makes Asian Americans look right. The people that I have found that care very deeply about how this makes Asian Americans look like are writers, academics, and people who sort of advanced this new type of respectability politics, right, that we must always be perfect in our politics, we must always be progressive.… So there’s an attempt to make the assimilated Asian American not seem like they want to be assimilated, that’s the first tenet. And the second one is to make them into a multicultural elite where they don’t have to apologize for their community, that they can say, “Actually, our people are just like your people, and they should work together.” It is an erasure, to use their terminology, it is an erasure of how people actually think.… And if we ignore that, if we say that that’s not real, or we say that those people don’t count, then what are we doing? I just don’t understand that impulse at all. It is deeply a respectability impulse.

TKN

Respectable to whom? You’re kind of flipping the idea of what respectability politics is, it’s like respectability to basically Black people and coalition politics—

JCK

Right, right, right. So that’s the thing.

TKN

Not the white world. So do you want to expand on that?

JCK

My sense of this is that there comes a time when most Asian people who are upwardly mobile and coming around in the world really do stop caring so much about what white people think about them. In some ways they kind of write white people off. They might have white friends or whatever but they don’t really care what those white friends think about them so much. The thing that assimilated, upwardly mobile Asian Americans within progressive spaces care about deeply is what Black people think about them. You know that that’s true just as much as I do, that’s who they really care about what they think. And that’s because they want to feel like POCs. They want to be able to take part in progressive politics as somebody who has a stake in it. And I understand that impulse quite deeply—I think that that’s an important thing and I think that they should do that. But I think that they feel that they need to scrub off all the ugly parts of their community, that they have to always apologize for them. That’s why when George Floyd happens, it is not that all Asian Americans who are progressive start marching on the streets in solidarity with everybody else. They do that, right? But first they have to apologize for anti-Blackness in the Asian community. What’s that about, right? Did anyone ask them to apologize for anti-Blackness in the Asian community? No, it’s a cleansing impulse to say, “I am not like them.” It is a distancing, and I do think that that’s its own form of respectability politics. It’s not aimed at white people, it is aimed at a multicultural elite, or the idea of a multicultural elite. And I actually think that is sort of the animating engine behind progressive Asian America right now, this sort of “we must always apologize,” or “we must always eliminate those of us who would embarrass us within this group.”

TKN

This has been a concern I’ve had sometimes when I’ve read your various writings in the last several years, and it was a concern I still had when I read your book—sometimes I feel like you fetishize grassroots organizing. But part of the history, if you don’t know, of people critiquing and developing a critique of anti-Blackness took place in those organizing spaces. You’re kind of saying, some of the social justice language that people use in these spaces is elite or appealing to elites, but you have people who are trying to push these conversations in these grassroots organizing spaces. And I don’t think you deal with that in your analysis.

JCK

I think that’s a fair thing to point out. I think it’s a fair criticism of the book. But I would say that my vision of what this could look like in the future is much broader. There are great challenges in organizing different groups of people together, especially recent immigrants. They’re gonna cling together.… I remember I was talking to a friend of mine. And she was like, “The way you write about politics is that you have this hope that we can organize all these recent immigrants, for example, who are very, very vocal against affirmative action, and who vote for Trump, and who hate changing Stuyvesant and all these schools.” And she said, “They’re gone, they’re just Republicans, you should just think about them that way. There’s [no way] they’re going to be persuaded back to our side.” And I think she might be right. So I understand that there are these challenges out there. I also think there are so many people who were politically engaged in their home countries who come over here and can’t navigate the American political system. There are many reasons for that. If you look at the data, one thing that really sticks about Asian Americans is that the [political] outreach to them is way lower than any other group.

TKN

Your book helped me understand more your critique of people employing social justice critiques of Asian Americans because of these reasons that we’re talking about, and that you can’t create a specific kind of portrait of a good, social justice Asian American and really think you’re really getting at the way a lot of Asian Americans are actually doing politics and shaping the conversation about being Asian American. You can’t just hide them away out of this sense of shame of wanting to look like a good coalition partner. And when I read your book, that resonated with me because I’ve done different talks, and one of the biggest questions that comes up all the time from Asian Americans, particularly young Asian Americans, is “How do we confront anti-Blackness in our communities?” And one of the things that I say is that we can’t disappear all these people that might politically embarrass us.

JCK

So we agree about that, right?

TKN

So we agree about that. I think what I have concerns about is, do you think your critique could suggest that talking about anti-Blackness is an elite preoccupation?

JCK

Well, yeah, um—

TKN

So you do think that?

JCK

Right.

TKN

And that’s what I get concerned about.… I think in your critique, there’s this way where you almost suggest that dealing with anti-Blackness isn’t relevant to working-class and poor communities or to bettering the conditions that people are in. And this is where I would disagree with you. Part of the history of labor organizing is dealing with people’s racism. There’s a history of dealing with racial conflict or anti-Blackness on a working-class level to achieve some of the work that you’re trying to get at. And I feel like some of your critiques about anti-Blackness and critiques of gestures of solidarity as being elitist don’t really account for that.

JCK

Sure. I don’t want to be misunderstood here and say that trying to combat anti-Blackness is a bad thing. I think it’s a really good thing, obviously, I think that it’s a good thing. I think that my critique is not necessarily so much about the space that it takes in places where it is very necessary, like the conditions you were talking about. Like, you can’t build a coalition if one of the groups hates the other group and doesn’t trust them or thinks that they’re degenerate or whatever racist thing that they think. I’m sort of speaking more about the place of this performative critique of anti-Blackness in the larger discourse around race in America and around Asian Americans. I agree there are contexts where it should be front and center. Right. But I do think that there is sort of an elite preoccupation with it in a way that does feel like it is a purging of one’s community.

The example that I’ve given in the past is kids who were like, “We’re Ivy League students and we’re writing letters home to our communities about anti-Blackness.” And this was right as the George Floyd protests are wrapping up. And so you think, well what’s that about, what are those kids doing? I don’t judge those kids, like I said. They’re trying to engage in a protest action, and I think that that’s sacred. I think that’s the most important thing they can do. But the thing that I would say to them is, “Why are you identifying yourselves as Ivy Leaguers? And what are you trying to say by the performance?” Well, you’re trying to say that “we are very accomplished people,” but you are also saying that “we are not like these other Asians who are racist.” You’re distancing yourself from the community, and I do think that’s a form of respectability. But I also think that it’s totally empty. It’s about the individuals being accepted and having permission to protest. Giving themselves permission to enter that space without being accused of being anti-Black. I have been to many, many, many, many protests.… I say just show up. You don’t have to do this whole thing where you cast off all the ugly people in your own community, you know? You don’t have to distance yourself from all of that. You can just show up now. They’re trying to position themselves as being worthy partners, and I understand why they feel like they have to do that, but I am trying to tell you that you don’t have to do that. Show up and that’s enough, and you can leave all this neurosis behind.

TKN

So your book contract gets announced around 2017. You basically have the same thesis as you do in your New York Times Magazine piece about fraternity hazing, and that’s also where your book title comes from. Did your thinking go through shifts? Did you feel conflicted about some of your arguments in the last four years as all this stuff is happening?

JCK

Yeah, I think it changed in that in 2015, 2016, I was much less charitable with my thinking about the Asian American elite, of which I also am one. I understood the criticisms that I could make of myself, and I felt that that entitled me to also criticize people around me who I felt were acting in similar ways. One of the things that changed during the pandemic and during the attacks, especially after Atlanta, was that I began to think about us, if we are a people—something you know I feel very conflicted about. That if there is an Asian American people, they’re scared more than anything, and that fear is the great motivating factor behind many decisions, not just for people who are being attacked, but also people like me. When you think about people who are afraid, you feel much more sympathy towards them and you try to understand their actions in a positive light, or at least a sympathetic light. And the pandemic did make me start thinking much more along those terms because I was also afraid. And I think that has made me more sympathetic, and I don’t think that that will end.… I think I’m much more thoughtful about some of the scholarship than I was five years ago, and I think that changed as I wrote the book. And so there are ways in which I do not believe in going back and scrubbing everything in the last edit to make it all aligned together.