“As a writer, as someone who reveals their innermost selves linguistically, it’s lonely not to speak the same language as your parents.”

March 29, 2021

Over the past two decades, Mary H.K. Choi has written comic books, hosted podcasts, starred in public health PSAs, interviewed Rihanna, put La Croix in the New York Times, got sober, and introduced the world to the finely-drawn, totally #TooReal characters who populate a young adult universe drawn from her own itinerant life and experiences. After dropping instant classics Emergency Contact and Permanent Record, the latter of which she’s adapting for the movies, Choi’s latest novel is her most personal yet: Yolk (out now from Simon & Schuster) is, on the surface, a tale of two Korean American sisters bound to each other by the gruesomeness of their bodies: younger sis Jayne keeps older sis June’s cancer diagnosis a secret from their parents while June keeps mum about Jayne’s history of disordered eating. But poke its veneer and Yolk splits open into a messy, furious, hilarious, and heartbreaking account of sickness and health, food and comfort, family and blood and guts, and maybe, glory.

If I were someone who made vision boards, Choi’s career path would be front and center. But to hear her describe her artist’s journey over an hour-long phone call, all it’s taken is her entire life to even look her desires in the face. Even now, she still sometimes turns away. But Yolk is a book about taking the things you’d rather keep hidden and forcing them into the light. Speaking through Jayne Baek, a Texas-to-New York transplant whose heart gushes love like a mortal affliction, Choi writes toward recovery. What does it take to forgive a city, a man (unless he steals your Shin Ramyun Black), a sister, a father, a mother; your past, present, and future selves? Well, you can’t make ttukbaegi gyeranjjim without cracking a few eggs.

— Lio Min

LM: I’m fascinated by the way you’ve moved between mediums throughout your whole career. What’s it like to be on the other side of the glass? Both in the sense that you used to be the person asking the questions and now you’re largely the person answering them. And also, your beat used to be pretty much anything that fell under the banner of “culture,” and now you’re in a position where you’re actually creating culture, specifically YA culture.

MHKC: It’s been really scary. I think I found it almost dangerous to give too much credence to the suspicion that I wanted to create something. I just don’t know how I could fathom the level of heartbreak, not only if I tried it and failed but if I didn’t try it at all. Both sides of that particular coin just seemed so devastating and not something that any sort of person in my position should endure willingly.

I think it would’ve been really different if creativity as a life force or a construct or a system or a viable output that you could make a living at was presented to me at any point during my childhood, my formative years, my teenagehood or even my young adulthood. But I didn’t have any of those examples. No one I knew was a writer. When my parents moved to America, they immediately went into restaurants because of the very foundational, lowest hanging fruit of like, well people need to eat.

I’ve talked about this before, but I thought it would be less heartbreaking if I was close to writing but not inside of it. I was an editor first and not even any editor, I was a managing editor. You’re helping writers, not even directly behind writers but near them. Writer-adjacent. I had to mince my way and cross that Rubicon really gradually. I got to a point just, as a person making things, where the prospect of levying some kind of verdict on the creation of other people just felt more and more unjustifiable. As things got flattened, as algorithms got more self-soothing and pacifying and designed to be more and more seductive, I felt like deciding what’s an A, what’s a B, what’s a C and all of that got more and more craven and dirty. I thought at that point that maybe I would actually take a stab at try[ing] to create something and finish it and see what happened.

I have had my heart broken in media so many times and that trauma and stress of like, genuinely feeling the floor is just gonna come out from under you at any point, that hyper-vigilance that you feel in your jaw and your shoulders and your neck and your lumbar, I just carried that around with me all the time. And so I started writing fiction! Obviously, there’s no security in there either but at least I was gonna finally admit to myself that this was something that I wanted to at least attempt.

LM: What I appreciate across your books is that you return to a lot of the same themes but examine them from different angles. What made Yolk the book that you did now?

MHKC: I knew I wanted to write about how genuinely biological and gruesome being a woman is. Especially if you’re moving to an aspirational place and you have this pressure that you have to also become a certain person so as not to be rejected by that aspirational place.

Magazines have always been important to me, I love, love magazines… Talk about getting your heart broken. I’m like Charlie Brown and the fricking football and Lucy is magazines. At the time [magazines] were like, how do you move from day to night with your office look? How do you dress so you look ten pounds lighter? How do you dress so that people take you seriously? I was like, if I don’t present in a certain way when I get to New York, I’m going to get eaten alive.

The only armor that I knew to have was, look a certain way. The only tool I’ve had to cope with feelings my whole life was food. Because I grew up with workaholic parents in an immigrant house, and my parents were in the restaurant industry, [you feel] if you’re clothed and you have housing and you have food on the table, then you should be good. Everything beyond that is fairly superfluous, if not indulgent. I didn’t know how to process any feelings beyond eating over it or getting drunk over it. Getting high. My eating disorder had been a part of my coping mechanism since I was in my early teens. [In New York] it just exploded.

There’s this expectation too that once you graduated college, you’ve sussed out a few things about yourself, you’ve figured out what you want in life. But that was not my story; I did not know how to have a single feeling beyond hunger until I sought recovery from my eating disorder three years ago, in my late 30s. [In Yolk], I wanted to talk about the very specific ways in which my thinking was really broken, and I wanted it to be in the backdrop of a very well-worn, classic coming-of-age thing of a fish out of water.

LM: What you were describing about growing up in an environment of, “If you have these things in your life, everything else doesn’t have to be talked about.” Suffering that you don’t ever hear about but is this ambient feeling… Everybody knows it’s there but nobody really wants to talk about it in the way that actually processes anything.

MHKC: In my culture and a lot of different cultures, suffering is par for the course. And it’s honorable and noble and about forsaking the individual for… not even upward mobility but the good of the collective.

Of all suffering, the one that really is the most hierarchically, borderline divine, is silent suffering. When you’re young, silent suffering and secrets—that’s a really felted together, gnarly enmeshment. Any household in which your family behaves one way behind closed doors and then outwardly or in public or at church, the workplace, you’re like, whatever’s different must be a secret. And I’ve been taught that secrets and silence and shame go hand in hand.

There’s almost honor in keeping secrets for other people no matter how corrosive it is to that person and to yourself and to the family at large. In my experience, the lack of interrogation of that just becomes heavier and heavier and heavier. You have no understanding of what is shame, where the shame came from. It’s so immediate and automatic, and what part of that is guilt? What part of that is even yours to carry?

That’s really pervasive. If there’s something really fucked up happening in your house, it feels like the greatest sign of loyalty and self-gaslighting to where you can believe it’s not happening or it’s okay, if you don’t talk about it. How many kids of alcoholics or dysfunctional people or addicts, if they’re little enough, just know and understand the rules and don’t talk about it and don’t talk about it with each other?

LM: That feeling of loyalty that’s bred out of the idea that no one can protect them the way that you can protect them. And in the book and in real life, it’s not necessarily a parent to child relationship, it’s a child to parent, child to someone else who in theory has it more together.

MHKC: That’s the whole thing about the whole inter-generational tapestry and the systems that work within, in my case, immigrant families, where your parents don’t necessarily speak English. There are so many role reversals where you’re translating or someone’s, god forbid, trying to rip them off, or you’re figuring out the aftermath of them getting ripped off in some weird American bureaucracy commodified Ponzi scheme. When you’re a kid and you’re doing that, and then on the flip side your parents are extremely strict and harsh and don’t necessarily explain anything because of this cultural breach between the two of you that feels insurmountable, it’s really confusing and disorienting. But then you have to blindly honor and obey them and listen to them.

I love my parents. I’m clearly obsessed with my parents but like, there is an aspect where speaking truthfully about who they are and the things that happened within our family, even just acknowledging that they happened at all feels like an indictment. In so many families, I feel like the admission of the truth feels like a betrayal. I don’t know any young person who doesn’t experience this.

LM: The almost magical part of YA fiction is that it allows you to… not exactly play with the way that you process emotions, but explicitly wants you to do that processing. I feel like when you adapt this material into something visual, sometimes that processing doesn’t get carried along. The reading relationship doesn’t instruct you to react a certain way that film and TV sometimes does.

All that said! You have a project that’s going through the translation process right now [the film adaptation of Permanent Record]. What’s it been like to take this thing that you made, that you’ve become a vessel for, and move it into something else?

MHKC: To me, there are so many parallels between YA and horror as genres. You have these really heightened stressors in YA because of the newness of it and the stakes feeling high because you’ve never experienced any of this before. You don’t have references; you don’t have muscle memory. And then in horror, because the stakes are literally freaking high and paranormal!

I love that catharsis. You can have it while being extremely measured about how prescriptive you want the storytelling to be. The people who read YA are phenomenal and trustworthy and have amazing taste. But the moment you become prescriptive, the moment you become cautionary, all of that credibility you have as an author completely goes out the window. Young people don’t need to be infantilized, pacified, patronized, or explained to. The YA reader is tough and there’s that sort of tension, that sword of Damocles, so far as they will love you, they will support you, but the second you betray that it’s like, who is she? I don’t know her.

I take that super fucking seriously! With that in mind, even with adaptations—I’m writing the script for Permanent Record—how do I preserve that bond? How do I earn this trust in another medium in which I don’t know what I’m doing? What I’m learning through the people that I’m collaborating with is, how do I just take the essential characters and the taste of what they are, the nuance of the story, without necessarily being married to this one iteration of this story?

LM: Books take a long time, movies take a long time, and you read or watch some things where the setting is clearly incidental. But your books are so rooted in these specific snapshots that somehow end up feeling timeless, even though of course these places have changed and will change.

There’s this intimacy to places and the idea of being in-between these places that, I don’t mean to be like, this is an immigrant thing! But there’s something about home being someplace your parents haven’t seen in decades that feels present in your books. How do you write this timeless window while acknowledging a reality that was, is, and will be?

MHKC: I moved to Hong Kong when I was eleven months old. I don’t think this is the experience for a lot of people but, Hong Kong agreed with me. Every time I would get on public transportation there as a small child—we were such latchkey children—I felt genuine gratitude and abundance and appreciation. I loved the way it looked, I loved the neon, I loved looking at like, Wong Kar-Wai, Chris Doyle cinematography, and being like, I know what these places smell like. I know how the air feels thick on my skin, I rush past this alleyway because it scares me, that 7/11 is two meters from the other 7/11.

So when I moved to Texas, it was obliterating. Everything about myself atomized. Actually, it’s so clear that I became bulimic the year that I moved to Texas. I couldn’t geolocate my own body in this huge expanse of land and sky. If you’re 13, 14, and this is happening, it’s so seductive. There is no velvet cocoon quite like total isolation and somatic annihilation. I preferred not existing. That’s a very useful tool for assimilation.

I knew that Hong Kong was going to be handed over in 1997. I opted for New York because it was almost like, this place looks close enough to Hong Kong that I could imprint there. So not only was me moving to New York a foregone conclusion but the expectation that I would be able to locate my body was so high. I just wanted to go home, I was so tired. When I write about place, it’s about how I felt and how it made me feel. And what I expected to feel when I got there, and maybe that not happening, and how heartbreaking it is.

LM: A friend of mine has this saying, that there are three kinds of writing. Head writing, heart writing, and guts writing. So much of the way that you’re describing your writing and that one feels as they go through your books is that gut-level everything. And I’m not just saying that because Yolk is about food.

When you’re writing about this kind of stuff, there can be a tendency to glomp onto the page and start leaking. Now that you’re in the process of looking at that and being like, “And now I’m going to keep talking about this,” what kinds of practices do you might have in place to keep that part of it fresh and something you can access readily, without falling head over heels every time you have to do that? And I realize I’m asking you this on a call where we’re doing it.

MHKC: As difficult as writing is and as harrowing as editing can be, I do not know of a more painful extraction of a pound of flesh quite like publicity for a book.

There’s something sort of cathartic about a book being out and then holding it, the tactile sensation of it being in your hand. Even when you sign someone else’s book and you hand it to them, it’s a dispatch, or a blessing. I don’t have that system in place so it feels like a lot of giving, giving, giving, and then silence, which by the nature of my hardwiring, feels like rejection.

I have dysmorphia; I’m not the best gauge of what reality is as it surrounds my physical appearance. The idea of doing a book tour where I’m not just looking at an audience but I’m looking at myself… The uncanny valley is so strong and the revulsion, the recoil is so strong. I have so much support in my life; there is not a single secret in my life that someone who loves me doesn’t know about. But this particular tour is so scary and this book is really scary. In a lot of ways, this book feels like the most blatantly autobiographical, so it does feel like a rolling rejection in the lead-up to this. But there’s not a whole lot I can do to convince my little brain, who’s just in this little cat carrier.

It’s not talking about eating disorders that’s hard, it’s not talking about something that is also a part of the story, which is that my mother was diagnosed with cancer as I was writing this book. That’s sad but it’s not hard. This constant feeling of, please accept me, please please accept me, that doesn’t feel like it has an answer, is really hard.

LM: For what it’s worth, thank you for writing this book. I sat with it for a long time after I finished it, thinking about my parents, a lot. And my sister.

MHKC: It’s so painful being in a family! Just because it’s painful for everyone doesn’t mean that it’s less painful for everyone.

LM: There were so many moments of revulsion and then you start thinking, why are you repulsed by this? That moment—and Jayne does this—where you’re looking in the mirror and you see this thing, and you’re like that’s me, huh? This is what it means to be young and careening through a city that you’re thinking is the place that you want to be forever, and yet feels like it’s rejecting you at every overture. That’s pretty fucking real!

MHKC: Even with being Asian right now… All of these violent attacks touch a confirmation of a horrible suspicion that we’ve had about everyone and the way they relate to us. It feels like the rejection that we’ve been bracing ourselves for, our whole lives.

LM: I read Minor Feelings by Cathy Park Hong—

MHKC: Oh my goddd.

LM: —yeah, right? That was honestly one of the first times where I felt like someone really got it. Like yes, of course, being Asian American is about any number of things, but this is it, right? It’s like looking over your shoulder for something that you’re pretty sure isn’t there, until it is.

MHKC: [Asian Americans] spend so much time looking for evidence, expecting to be cross-examined about how real our feelings are. And feeling as though, time and time again, that our evidence is not enough to prove that these things that are happening are happening. Time and time again, the conversation about erasure is about whitewashing in Hollywood and I’m like, sure, fine, but it’s also that we don’t track. Racism against us doesn’t count. It’s irony, it’s wit, it’s humor, it’s less important, less urgent than. “Oh, racism against you is thinking you’re perfect?” It’s so quieting in exactly the way that we’re hardwired. And that’s the part that feels like such betrayal. Our own ingredients are being turned against us. Our own parents, our own forebears, our own cultures, our own systems. Our own honor code is killing us.

LM: I interviewed the pop star Rina Sawayama last year, and something she said really stuck with me. To paraphrase: the reason why you don’t see many Asian pop stars outside of Asia is because the ecosystem, the village you need to bring someone up to that height, it has to be so absolute and so grounded in dreams. Supporting someone even if they don’t make their dream, even if it ends up backfiring, even if it changes. Our people don’t really like to do that when there’s no guarantee.

MHKC: We really like a guarantee! We really fuck with guarantees!

LM: There’s only a bullseye. The rest of the target doesn’t exist.

MHKC: Because it was too expensive to get here!

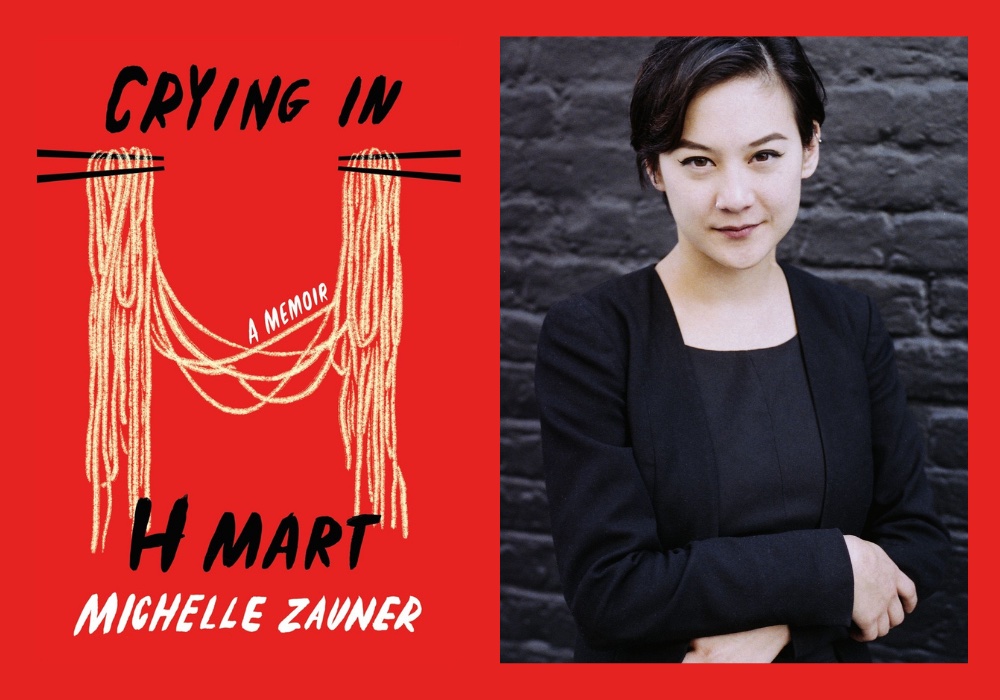

LM: When I interviewed the Korean American musician Japanese Breakfast a couple of years ago, she said that dreams are really important in the culture. There are several moments in Yolk where dreams are brought up as portends. In as least, but also as most wishy-washy and woo-woo way as you want to get, what is your relationship to dreams?

MHKC: I dream pretty much every night. I don’t usually remember them. I talk in my sleep so sometimes my partner lets me know what was said. These past few weeks, some of the notable quotables from my dreams have been, “Do you think I should call him out?” and also, “No! Fuck off!” I also cry a lot in my sleep… There’s probably some unexpressed grief there, I don’t really know what’s going on.

I also really really believe in the power of intention. Dreams being woo-woo is some shit that can really discourage you from making things into reality. I’m all about vision boarding and being declarative about things that you want. I say that only because it took me 40 years to realize that you need to know where the fuck you’re going. You need to know where your North Star is so you can incrementally, gently, and purposefully make your way toward that. Dreaming massively is really helpful. Saying things out loud that make you laugh or feel a little bit ridiculous is really helpful too.

LM: You have to wonder, did our parents make vision boards? How do you immigrate without having something like that?

MHKC: That’s what I mean, there are so many situations where we’re like, oh the thing about immigrant parents is, blah blah blah. But yo, these motherfuckers were fucking pirates and astronauts!

A few days after our phone conversation, I asked Choi’s book publicist to pass on one more question:

LM: What is your parents’ reaction/relationship to your writing, then and now?

MHKC: My parents don’t read my work. It’s both such a source of tenderness and a massive relief. Of course, there’s a part of me that yearns to be understood in this way. Especially by them. For them to see the way I think and the way I speak and possibly be proud of me with a sense of precision, recognition, or familiarity.

As a writer, as someone who reveals their innermost selves linguistically, it’s lonely not to speak the same language as your parents. Then again, the fact that my books haven’t been translated into Korean is incredibly freeing. I don’t know that I’d want to be swayed in any way, or feel as though I’m aiming for a version of work that would gain the most approval. I think it wouldn’t even be intentional but I’d feel the weight of it and can imagine it would be stultifying.

The books are a gift. It’s the best of everything. It’s not as scary for them as when I worked for various art magazines that they couldn’t find in Texas. I think it’s gratifying that they can see evidence of my work in big-box stores—proof that I’m not starving to death in New York—while not having to be burdened by knowing too much. Maybe it’d be too intimate for everyone.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.