Through the radio speakers / I hear a woman shivering. I think of my friend, newly pregnant, / also on her way to work, how she’ll twist a ring off her swollen finger.

February 22, 2021

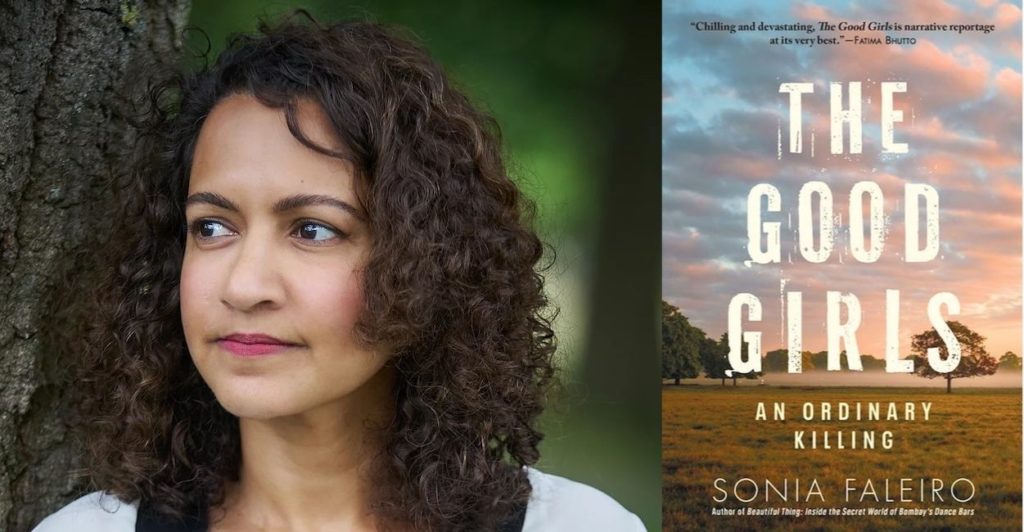

Editor’s Note: The following essay is part of the notebook #WeToo, a collection of work published both in the Journal of Asian American Studies and in part here on The Margins. Together, this body of work provides language and theory for lived-experiences of sexual violence in what is usually dismissed as privileged, unafflicted model-minority life. The #WeToo collection is edited by erin Khuê Ninh and Shireen Roshanravan. Accompanying the series on The Margins is artwork by Catalina Ouyang.

The following essay includes mention of sexual violence and rape culture. Please take care while reading.

Read more from the series here. And continue reading work from the full collection in the February 2021 issue of the Journal of Asian American Studies, which you can purchase here.

Such luck, I think—driving to work, wheels skidding

to a hard stop when a chipmunk darts in front of my car,

pauses, then scurries back into the browning shrubs.

Motionless in that moment, the possibility of one

outcome gives way to another. Then breath, then the voices

on the radio, then they’re saying my name—no, the name

of Dr. Christine Blasey Ford, who has entered the Senate Chamber,

taken a seat. I look around at the empty street, press the pedal.

In exaggerated whispers, the reporters blithely describe her, surprised

she’s not a “surfer girl,” as a woman “under a lot of pressure.”

I’m late for work, unusual for me, but earlier this morning

had heard from a friend about another friend, that her husband

has left her, just months after their marriage and announced pregnancy.

What terrible luck, I said, then wanted to take back, not sure if “luck”

was the right word. This news, and the news on the radio, skirt

each other in my mind, strike sparks when they get close.

Then this: in college, I waitressed at a Korean-owned sushi restaurant

in an unassuming strip mall where I would arrive straight

from class, apply lipstick and eyeliner using a simmering pot

of miso soup as a mirror next to the chefs knifing clean the fish,

sloughed scales sharp and translucent like chips of glass.

It was luck that had gotten me the job, or so I believed—

over eighteen and authentically Japanese (half, anyway)

and enough comprehension of Korean (the other half) to get by

in the kitchen. Korean enough to not question tossing salt

on the front stoop to chase away bad luck,

like that night a man walked into the restaurant,

lifted his hoodie just enough to reveal the triangle butt

of a gun tucked into the waistband of his jeans,

then walked out with our fishbowl of dollar tips.

My boss’s mother, the cook, ran from the kitchen hurling

fistfuls of salt, cursing the gods, her son, and me.

I admit I was distracted by the greasy swastika inked

across the man’s throat, can still see the wound’s wet.

Then, not so much bad luck but still rude, one time an ahjumma

from my boss’s gye group tossed a crumpled napkin at me,

which hit my chest before landing on a tray I was carrying.

And many customers would, at some point as we ferried

platters of raw fish to their tables ask us

where we were from, where we learned to speak

English. Once, a table of white men asks to make me

a deal: they’ll bring me a pie if I say, “Me love you long time.”

They’re older than me, but not by much; they wear trucker-style caps

backwards, the mesh pressing into their pale, fleshy foreheads.

I remember then the sound of their laughter, then their faces reddening,

then the odor of sweat and hormones and stale beer, and the words

spilling out my mouth before I had full comprehension:

“What kind of pie?” It was a joke, I thought, or think I thought,

but their howls sent a phantom finger down my spine.

After my shift, my boss handed me a wad of cash,

said the group had “tipped big,” to buy myself a hamburger

on the drive home. I counted the bills in my car, under a streetlamp

in the parking lot, all those soy sauce-stained one-dollar bills.

I think of myself then, nineteen years old, alone in a dark parking lot,

money fanned across my lap. Nothing but unearned luck has kept me

safe and alive these thirty-three years, a dumb, gift-luck

whose mouth I pry open every morning for inspection.

But not this morning. Through the radio speakers

I hear a woman shivering. I think of my friend, newly pregnant,

also on her way to work, how she’ll twist a ring off her swollen finger.

I think of the tattooed man’s eyes—what I thought was desperation

but maybe was not, was maybe hate, or power, or fear, or even

hunger—how I couldn’t hold his gaze, my eyes unable to resist

the twisted omen he’d chosen to stab into his flesh.

*

When I was nineteen, alone in that dark parking lot, dollar bills spread

on my lap, thinking (of all things) about a hamburger, I failed to notice

the white pickup truck that will pull out after me, follow me down

each side street, the red laughter of the men in my rearview mirror,

and for a breathless moment I recognize how this scene is narrowing

to that one outcome, how it feels inevitable, like the easing on

of a mask for a role I had been destined to play. But no. But what luck.

I lost them, made it to the anonymity of the freeway where I maneuvered

through five lanes of easy traffic, the chorus of identical brake lights

a radiant red shield. Despite the betrayal of my own mouth, through

no good choices of my own, I survived. But is there no other word

for it than luck, or as my mother would later say, bok, fortune—

in her eyes, something you’re either born with,

or not. Such luck to get home safe

when so many do not; is there really no other word?

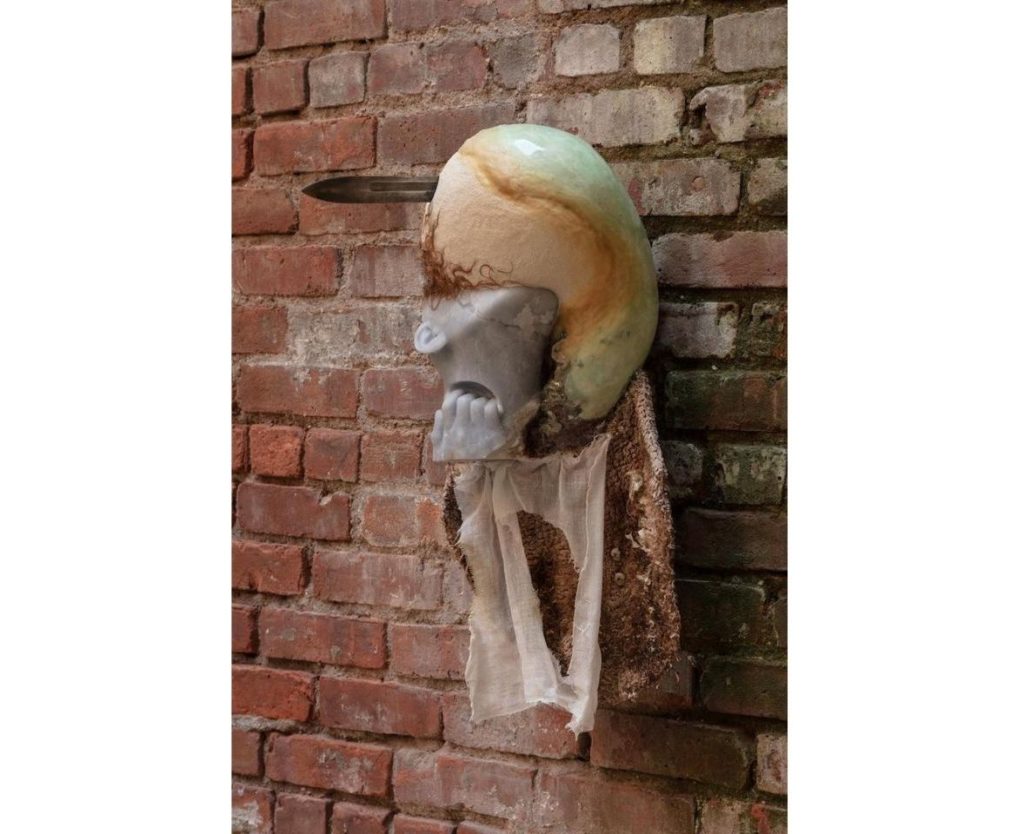

Pictured above, by Catalina Ouyang, exhibition view from DEATH DRIVE JOY RIDE:

The work DEATH DRIVE JOY RIDE (2018) drew connections between Ouyang’s research and writing on Chinese fox spirits, Medusa, diaspora, hybridity, mobility, girlhood, ancestral ghosts, and the American dream; she was exploring modes of finding/building community in myth-making and fantasy against a backdrop of late capitalism and ecological disaster. A central installation featured a found truck camper shell repurposed as a table, covered with ingredients in traditional Chinese medicine.