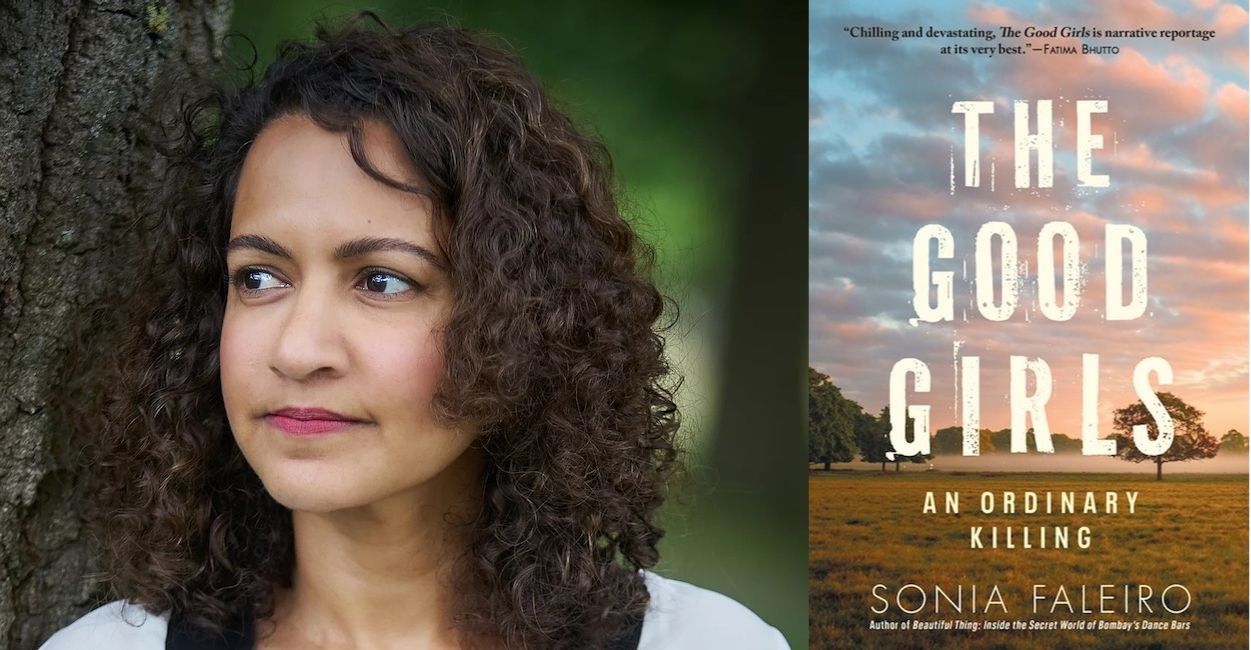

The investigative journalist and author of the true-crime book The Good Girls in an interview about honor, caste, and patriarchy in India.

March 22, 2021

Editor’s Note: The following feature includes mentions of sexual violence, rape, and murder. Please take care while reading.

There are so many ways for a woman to die in India. She can die in a temple, eight years old, drugged and gangraped. She can die while working in a field. She can die, set on fire, while traveling to testify at the trial of men accused of raping her. She can die on the side of a road, thrown off a bus after being gangraped.

The brutal rape and murder of Jyoti Singh [Nirbhaya] in Delhi in 2012 made headlines all over the world. Jyoti was on her way home in a bus after watching Life of Pi in the nation’s capital when she was gangraped, tortured and thrown off the bus. Her innocuous actions—inoffensive even by the high standards of a country prone to victim blaming—exposed, in the words of Indian investigative journalist Sonia Faleiro, “just how deadly public places were for women.” Faleiro, like many Indian women, was deeply affected by the depravity of the crime. Mulling over the culture of violence that besieged the city she knew so well, she thought, “Who were these men carrying out all these rapes, and why wasn’t anyone stopping them?” She sets out to answer this in her latest narrative nonfiction book. It is titled The Good Girls: An Ordinary Killing, but much about the deaths of two cousins, Padma and Lalli, at the center of Faleiro’s book is theatrical, from the image of the girls found hanging from a mango tree, clad in bright salwar kameez, swaying in the breeze, to the parental protests, internet infamy, media mania, and political pageantry that follows.

Indian law proscribes news outlets, writers, and journalists from publicly divulging the identity of rape victims due to the unbearable stigma that accompanies the crime, the specter of which can haunt families and loved ones for generations. Faleiro calls the girls Padma and Lalli, to remember the full humanity of these lives lost, to identify them in the statistics that obscure their existence, past the laws that protect and dehumanize in the same breath. So constantly together were they, that people called them PadmaLalli, like one person. PadmaLalli delighted in watching a play, PadmaLalli swept the courtyard, PadmaLalli dreamed, Padma lived, Lalli existed.

For five years Faleiro travelled from her home in London to Delhi, and then six hours to Katra-Sadatganj, in Uttar Pradesh where the hanging occurred, singularly determined to get the facts. Who killed Padma and Lalli? And because sexual violence was assumed, who raped them?

Faleiro’s oeuvre reveals a rigorous pursuit of the truth that is profoundly moving. In Beautiful Thing: Inside the Secret World of Bombay’s Dance Bars (2011), she shadows Leela, a dancer whose job is in danger—like 75,000 others—when the state of Maharashtra banned dance bars. While the murky glamour of the story drew the nation’s attention to it like flies to fruit, Faleiro knew that the story would slip away from the newspapers. “I couldn’t wrap my head around the fact that 75,000 women had their jobs taken away in a country where women’s employment numbers are already deplorable,” she told me over Zoom on a wintry February morning. “I couldn’t accept how casually we treat other people, and I was very distressed by the fact that we would forget something that I thought was unforgettable.”

Faleiro was devastated to see the same casual attitude in 2014 informing what became widely known as the Katra case. With the tenacity of a marathon runner, and the delicate precision of an embroiderer, Faleiro crafts an intricate true crime narrative that illuminates what it means to be a poor woman in India, the price of honor and shame, and the claustrophobic smother of caste and patriarchy. Her work is molded with care, her storytelling full of tender nuance.

Faleiro conducted hundreds of interviews with the girls’ families, the villagers, law enforcement, and medical personnel, revealing an investigation that was compromised by nearly everybody—including the girls’ families—with disastrous effects. While thousands of girls were reported abducted and murdered in Uttar Pradesh in 2014—the year Padma and Lalli went missing—the state was woefully unequipped to investigate these occurrences. In a particularly stomach-churning account, for example, Faleiro observes how Lala Ram, a sweeper entrusted with the post-mortem, used knives and hammers he purchased at a bazaar, and a set of scales he bought from a vegetable vendor.

There was, tragically, a quotidian quality to the girls’ deaths, which is why Faleiro designates it “An Ordinary Killing.” Conside how Uttar Pradesh has been anointed the murder capital of India, and in 2014 more than 12,000 people were kidnapped or abducted in that state alone. The girls’ families were well-aware that their destitution rendered them invisible, and they learned of the power of public outrage and protest from Nirbhaya. So they kept vigil by the tree their children hung from, refusing to let the bodies be brought down for one day and one night.

They were right. When the photos of the girls’ dangling bodies took over the internet, all of India’s systemic support apparatus materialized around them: from the press, to politicians and the police. “What offering support to grieving families in India essentially means is that politicians will give you money, if the case is high-profile,” Faleiro told me. “You’ll attract well-meaning social activists and lawyers, who for a certain time will be engaged with your case. But in terms of other support, like grief counsellors, they are such foreign things. Even our idea of how we provide support is uniquely and disturbingly Indian: your child has died, take money.”

But do these support systems inadvertently affect cases like this, and if so, how?

“The narrative that it ends up creating isn’t useful, it doesn’t really help the family,” Faleiro said. “One of the first things the media said about this case is that politicians were turning the village into an election rally, ‘politicizing’ the situation and the family’s grief. But that showed a lack of understanding of village life. The first crop of politicians didn’t turn up in Katra of their own volition, they were asked to come by the family. The support systems in India that are meant to assist the poorest aren’t fully functional. For them to work, you need the help of a politician, their mobile number. Then the politician provides short term assistance by calling up a school, or a hospital, or the police, and that’s meant to satisfy you. And that’s what you’re satisfied with because you know the system will not change.”

To assuage the public and the press, the police scrambled to deliver justice. But such was its nature: “Of the five men who were arrested, three people managed to escape from custody and get all the way to a bus station. A sweeper conducts the postmortem. But I would argue that things cannot go better in India, this investigation is the best it could’ve been. This is the tragedy,” said Faleiro.

When Faleiro went to the village on the fourth anniversary of the girls’ death, a cloud of sorrow hung over the family. “What is there to say, it happened so long ago,” Padma’s stepmother said to Faleiro. Other villagers—friends, teachers—echoed the sentiment: so long ago. “I think it comes from a place of deep despair,” Faleiro told me. “This place of: I can be unfixable in my grief, or I can just do what needs to be done. Who is going to milk the buffaloes, and tend to the fields? Life doesn’t just stop.”

But what is justice for Padma and Lalli’s families?

“In any circumstance [like this], justice is an investigation—scientific and objective—into the how and why of a crime. You may not accept it, but you believe it because of the science behind it,” said Faleiro. “But here, it would’ve been very difficult to get the [girls’] families to believe any investigation because it would’ve meant overcoming generations of mistrust. They feel in their bones that majority-caste people, upper-caste people, the police are determined to grind them down. And they’re fully justified in believing that because it is what happened to them. Under these circumstances, even if you present them with the best scenario—a thorough and scientific investigation—it’s unlikely they would have believed the outcome.”

This systemic mistrust runs deep in India, with women feeling perpetually betrayed by machinery that is meant to protect them. Victim-blaming is the norm, and law enforcement is so reviled that a 2015-16 governement study estimated that 99 percent of sexual assault cases go unreported. In a frantic flurry in the aftermath of Nirbhaya, the Indian Central Government meted out a series of reforms, like directing states to establish Fast Track Courts to deal with sexual assault offences. But there has been no uniformity in its implementation.

As for punishment, the sentence for rape was enhanced from seven years to imprisonment which could extend for life, and even the death penalty, despite studies showing that it isn’t an effective deterrent. When the men convicted in the Nirbhaya case were hanged to death in Tihar jail in Delhi, the country celebrated, bloodlust sated. National discourse around sexual violence remains submerged in a patriarchal well, with women denied personhood, existing in the Indian imagination only as mothers, daughters, sisters, and wives. “I don’t think the conversation around rape has changed all that much,” Faleiro said. “Aside from the attention that crimes against women are getting, I haven’t seen other changes. And without comprehensive change, justice is always going to be a piecemeal issue.”

As for the attention that women’s issues had in the aftermath of Nirbhaya, that too has dispelled under strongman Narendra Modi, despite his 2014 “zero tolerance” policy towards violence against women. An Oxfam India report early this year found that the Nirbhaya Fund—a $13 billion endowment to reduce violence against women—has been undermined by red tape, underspend, a lack of political will, and patriarchy.

Gender rights activists note the emphasis on protecting women’s honor rather than empowering them to exercise their rights is a major challenge. Honor so often is code for caste. In the opening chapter, Faleiro observes that 95 percent of Indians marry within their caste, and those who don’t attract attention. While official records in 2015 stated that 28 honor killings were reported around the country, everyone knew the numbers were in the hundreds, if not thousands.

Predictably, “honor” plays a role in the Katra case too. Padma, it turned out, had a phone—Faleiro notes that some villages in Uttar Pradesh banned unmarried women from using phones, portals as they are to a larger world, especially as a spate of “dishonorable” elopements were occurring around their hamlets. It also turned out that Padma used this phone to liaise with a boy from a different caste, with whom she began a sexual relationship.

This subject matter—honor—added another foggy layer obscuring Faleiro’s efforts. “One can fight over goats and boundary lines, but not over matters of honor because that is a life and death issue,” Faleiro said. “So, if you’re discussing a matter of honor, people will be guarded, because good relations are the bedrock of village life. The thinking goes: maybe the case will be solved, maybe not. Maybe we’ll know what happened, maybe not. But we have to live in this village, our children will live here, our grandchildren will live here, good relations must be maintained.”

In a place where “reputation was skin,” it is the maintenance of these “good relations” that makes a woman’s life everybody’s business. When villager, Rajiv Kumar, spied one of the girls with a phone to her ear, he grew angry, and contemplated informing their families of this transgression. It was his duty, after all. But telling them wasn’t without consequence for him—their parents might accuse him of slander—or the girls, for if word got out who would marry them? Ultimately, the accusation he levied: “the girls…are romancing someone” proved fatal. As Faleiro writes heartbreakingly, “It had been over for Padma the moment she was found with a boy, her salwar at her ankles. And for Lalli, too, by association. ”

What should have been a two-year project took Faleiro five, since she was navigating a track pockmarked with systemic obstacles. She told me that to report on true crime in India is to start with literally nothing. “I reported a story about a father in Uttar Pradesh whose children got trafficked to Nepal,” she recounted. “I went to India, then Nepal, but neither police station had case files, even though it had just happened. One of them actually said, ‘the mice must have eaten it!’ The level we are operating at is that basic.”

To be an investigative journalist in India is to be singularly tenacious in ones’ pursuit of the truth, an elusive, slippery thing. “You can choose to take a quote from a police officer, a lawyer, the victim’s family, the accused’s family and conclude your piece. But what are the chances that you’re ever going to find out anything real?” asked Faleiro.

To get to the facts while reporting The Good Girls, then, Faleiro had to be acutely aware of the environment in which she was operating, and to act with tact. “One has to understand that an individual can’t usually speak for themselves,” she said. “They exist as a part of large groups—families, villages—and are careful about not causing offence. What they say and mean can be two different things. Once you understand this, you see the enormity of the challenge you are up against.”

Since 2014—the year that Modi was first elected—the government has exercised control over the media in many ways, from pressuring advertisers to ordering tax investigations on news outlets. The government has also consistently discredited journalists, dismissing them as peddlers of fake news. This made Faleiro’s task even harder. “When I was reporting Beautiful Thing, people respected the fact that I was a journalist, that meant something. And since 2014, to be a journalist is to be despised and understandably so given cable news TV,” said Faleiro. “It’s perfectly possible to pick up a newspaper, or switch on a news channel, and not know what is happening in the country, or to be offered an alternate reality. People in villages don’t have a TV, they don’t read the papers, and yet it is filtered all the way to them that the media is untrustworthy and malicious. What they said [in The Good Girls] about the police is also what they believe about the media, which is the media will twist your words.”

Ethical standards for journalists are less stringent than in the United States, and the Indian media often exploits this to make bombastic stories of sensitive incidents. In The Good Girls, Faleiro chronicles the media’s unconscionable behavior, from outing the caste of the girls—erroneously—to reconstructing the alleged crime, depicting a woman being strangled as two male actors pulled apart her legs.

In Modi’s second term, the Indian press has been in the throes of a crisis, with journalists being subjected to outright violence. In these times, Faleiro’s exacting details and investigative deep dives are ever more precious. “There is a place for this sort of detailed, intimate, sensitive reporting [that you encounter in The Good Girls] that is entirely, 100 percent fact-based,” she said with cautious optimism. “People may consume all sorts of news and believe things that aren’t true, but the yearning to know the truth never goes away. And when they do finally come upon the truth, it becomes more valuable.”

The final truth of Faleiro’s investigation—who are the men who visit horrific violence on Indian women?—is an excoriating indictment of a culture of violence, how every head of the systemic hydra is rotten, feeding off the poor, the caste-oppressed, the women in a ruthless pursuit of self-interest. “I wouldn’t say it was men, or just men,” said Faleiro. “As for Padma and Lalli…We all did it.”

With the current political climate in India in which journalists’ critical coverage of Modi’s government is met with violence and censorship, we asked Sonia Faleiro to recommend publications and news outlets in India to subscribe to and support:

“Article14 addresses threats to and failures of justice and deficiencies in the legal system, tracks successes that can be built upon and discerns trends and patterns that require to be brought to the widest public attention. It takes its name from arguably the most important fundamental right conferred by the Constitution of India: ‘The State shall not deny to any person equality before the law or the equal protection of the laws within the territory of India.’”

“Alt News is an independent fact-checking website that is committed to debunking misinformation, disinformation, and mal-information that it encounter on a daily basis on social media as well as mainstream media. In addition to fact-checking, Alt News also covers news which the mainstream media often skips or provides inadequate coverage to, such as caste-based atrocities, religious discrimination, labour struggles, farmer struggles etc.”

“The Caravan is India’s first long-form narrative journalism magazine. It was relaunched in 2010 as a journal of politics and culture dedicated to meticulous reporting and the art of narrative. Since then, The Caravan has established itself as one of the country’s most respected and intellectually agile magazines, and set new benchmarks for Indian journalism.”

“Khabar Lahariya is India’s only independent feminist grassroots news network. Working out of 13 districts in Bundelkhand in the states of Uttar Pradesh & Madhya Pradesh, with an all-women team of reporters and editors from Dalit and other marginalized communities, Khabar Lahariya works on socio-economic-cultural transformation of the mediascape by its very presence and hardcore investigative journalism.”