A half-century of NYCs Chinatown history through the windows of the “Friendship Store”

October 13, 2021

Half a century ago, deep in Manhattan’s Chinatown, my father threw open the doors to a small shop on Catherine Street and sliced open the Iron Curtain. The store, crammed with imported groceries, its walls plastered in revolutionary posters, was on a mission to introduce the United States to exotic goods from a remote land: China. With its grand opening in September of 1971, the modest storefront was the only Chinatown retailer specializing in rare mainland imports like traditional crafts, dried fungi, herbal medicine, Mao’s Little Red Book, and records of the revolutionary anthem “The East is Red.”

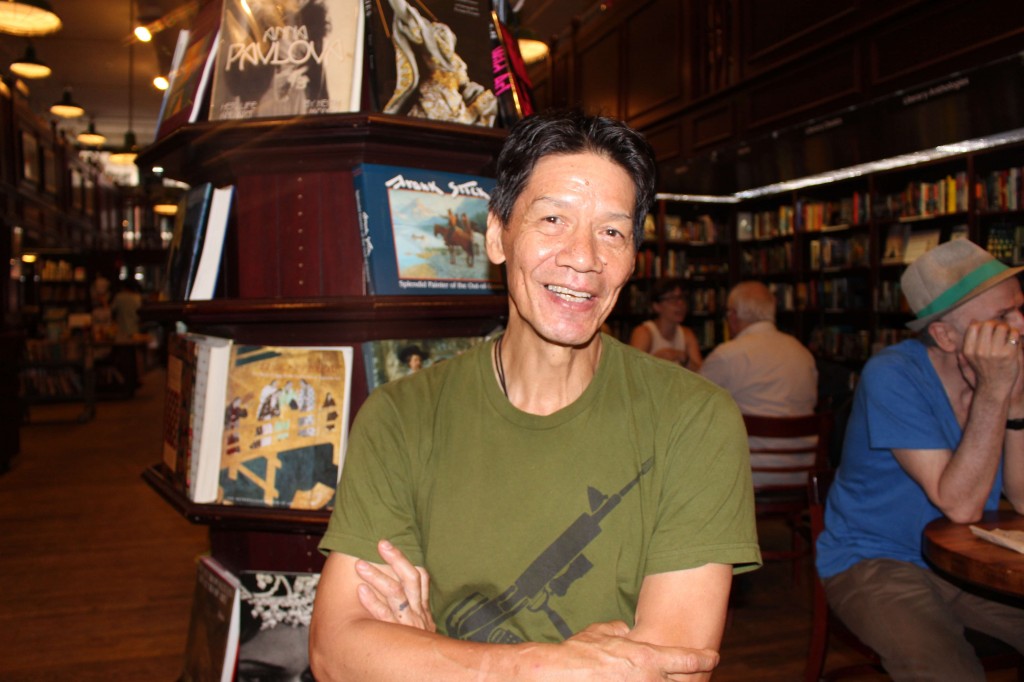

The simple inventory belied the store’s fraught political presence in Chinatown. The neighborhood was at the time a Western outpost in a diaspora that had been separated from the mainland by the Iron Curtain for about a generation, and the United States had not yet formally reopened diplomatic relations with China. The local Chinese immigrant business community was largely aligned with Taiwan, controlled by the exiled Nationalist party since the revolution in 1949. Broadcast news reporters covered the store’s opening as a harbinger of a prospective thaw of U.S.–China relations. That November, the Christian Science Monitor featured a photo of my father, Ming Yi Chen, as a smiling, bespectacled Taiwan-born chemistry doctorate-turned-shopkeeper in his early 30s, next to a shot of a socialist-realist poster on the wall declaring, “Keep Your Country in Your Heart, and the Whole World in Mind.”

To herald a new era for China and Chinatown, the store was named 四新 or “Four News” (after the Maoist slogan exhorting people to banish old ways and embrace “new customs, new culture, new habits, new ideas”), before it was rebranded as Pearl River Mart a few years later. The venture was founded on a whim by my father and a few other left-leaning immigrant comrades, including a Chinese translator at the United Nations and a veteran Chinatown laundry labor activist. In 1971, in the midst of the Vietnam War and an explosion of protest across the country, Chinatown seemed like it was ripe for change.

For Chinatowners, many of whom had migrated before 1949, the store was a portal to an estranged homeland. Despite the celebration of the Maoist vision of the Four News, many of the items—imported via an indirect route through Hong Kong or Canada—were laden with memory and nostalgia. Bottles of Pearl River Bridge soy sauce (referring to a key waterway and trade hub in Guangdong Province, and the namesake of the store itself) and other preserved foods were pungent reminders of their ancestral home, and reflected how much tradition had persisted despite the mainland’s communist transformation.

On opening day, my father, one of the only staffers at the time, encountered a tense hush before the storefront: “A lot of Chinatown people stayed outside watching—they don’t want to come in,” he recalls. At the time, some pro-Taiwan residents saw Si Xin as a political threat (at one point, the store was vandalized by anti-communist protesters). Some had been told it was “a communist store.” There were rumors circulating that the store’s canned food would poison them, and that, more plausibly, shopping there might trigger an FBI investigation. So understandably, my father says, the onlookers were “curious, suspicious and scared.”

Curiosity won out in the end. After some trepidation, people began rushing in. Pearl River went on to flourish as a retail outlet for all things China. While the store was not created with a profit motive in mind, banking on the China trade turned out to be a good investment: business mushroomed after Nixon’s visit to China and, later, the normalization of trade relations led the business to expand massively and, by the next decade, move the store out of Chinatown.

Pearl River’s expansion was fueled by its growing number of non-Chinese customers—initially leftists who were fascinated with communist knickknacks like the people’s revolutionary jackets. My father sold a legion of Mao outfits to a cadre of radical Harvard students. Though the original intention was to cater primarily to the Chinese immigrant community, there was always a cosmopolitan ethos behind the enterprise. Nicknamed the “friendship store”—a reference to the state-sponsored boutiques in mainland China that catered to foreigners—the founders’ hope was that cultural exchange could build peace and bridge political divides, inside and outside of Chinatown.

“My feeling was that Americans always had a lot of fantasies about China,” my father says. “[They were] very excited about Chinese culture, Chinese products… these two countries were attracted to each other,” so they were bound to connect again. And that mutual attraction still holds amid the current geopolitical tensions and trade rivalry.

As more “lao fan” (affectionate slang for a Western “barbarian”) were drawn to the store, capitalist consumption, not ideological affinity, became the main driver of trade with mainland China. Pearl River embodied a uniquely American cultural hybrid of commercial and political enterprise: Some shopped in solidarity with China and left with a bagful of cute tchotchkes, others came to buy groceries and acquired a new view of mainland China. Whether they supported Mao’s dictatorship or not, customers could see from the washcloths, chili sauces, and cotton slippers that the People’s Republic was made up of real people, whose lives swirled with familiar textures, colors, and tastes.

The Christian Science Monitor quoted my father and his first wife, another cofounder: “The ideas of communism are so distorted in this country. They should be more open to both sides—capitalism and communism. They each have good things and bad.”

Though he wasn’t entirely aware of it at the time, my father’s original mission of cultural diplomacy intersected with two transformations unfolding in Manhattan’s Chinatown. Following the liberalization of immigration controls in 1965, the neighborhood absorbed an influx of family-based migration, which spurred the transition of the community from a self-contained, service-based economy—dotted with restaurants and hand laundries—into an urban manufacturing hub, with hundreds of garment factories employing thousands of low-wage immigrant women. These women sewed cheap clothes under brutal conditions, just like the Eastern and Southern European migrant women who preceded them. For this new crop of Chinatown denizens, Pearl River was a family department store where a whole household could be outfitted with Chinese products—the silk comforters on their beds, porcelain tea sets and glass thermoses, Bigen hair dye in infinite shades of black, ginseng roots, and embroidered baby shoes.

Another development that paralleled the growth of the Chinese immigrant community was the emergence of “Asian American” identity among younger, American-born descendants of immigrants. In the early 1970s, the Civil Rights and Third World Marxist movements inspired descendants of Asian immigrants to generate a movement of their own. Their identity—uniting across racial and ethnic lines, across diasporas and between generations—was forged out of solidarity on two fronts: opposition to imperialism, and social justice for immigrant communities. Chinatown became a laboratory for organizing and volunteer initiatives, such as a groundbreaking community health fair. Young academics with the Chinatown Study Group surveyed the neighborhood’s economic deprivation. The artist collective Basement Workshop produced revolutionary prints. Militant Marxists I Wor Kuen fashioned themselves after Mao’s Red Guard.

Since it was mostly the creation of intellectuals in the Chinese diaspora and not Americans of Asian descent, Pearl River was not part of the Asian American movement. But it was a symbolic space and cultural resource for those early Asian American activists. Festooned with Maoist poster art and People’s Liberation Army–inspired garb, the store embodied leftist solidarity in the Chinese diaspora.

Working-class Chinese immigrants, pro-mainland intelligentsia-turned-entrepreneurs, and Asian American activists were separate strands of Chinatown’s social fabric. However, they braided together in their drive to seed new forms of community in a generations-old neighborhood at the frontier between tradition and radicalism.

During the 1980s and 1990s—when I grew up hanging around in the store—Pearl River’s customer base began to evolve from mostly Chinese immigrants to tourists and non-Asian shoppers. Accordingly, the store moved out of Chinatown’s core, from Catherine to Elizabeth Street, and later to SoHo and Chelsea, driven by skyrocketing rents as well as the realization that its main footfall was not coming from within Chinatown proper.

While China became unabashedly capitalist, Pearl River evolved into a dazzling pan-Asian emporium full of brocade fashions, rattan birdcages, and gummy snacks—the Red China regalia is now largely limited to some tongue-in-cheek Mao agitprop art and cotton caps. Chinatown’s radicalism has softened as well. As the fractious 1970s yielded to the neoliberal era of the 1980s, the neighborhood’s political landscape became less defined by the Asian American movement’s grassroots interventions, and more dominated by institutionalized community development and social service organizations.

Yet it feels like Chinatown and its cultural infrastructure needs the ethos of radical solidarity more than ever today. The COVID-19 pandemic has woven China, Chinatown, and the Asian American community more tightly together, both in fear and resilience. The disease former President Trump called the “China virus” became a badge of stigma and contributed to economic devastation in Chinatowns and Chinese-owned businesses across the country, which also coincided with a surge in anti-Asian attacks. As Asian American activists organized against anti-Asian violence during the pandemic—setting up mutual aid and grassroots support networks to protect communities traumatized by the pandemic—many also mobilized in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter protests under the banner of Asians for Black Lives.

Chinatown, as a social and political space, has survived hardships before, of course: the collapse of the garment industry with the surge of globalization and outsourcing in the 1990s, the turmoil of September 11 and its aftermath in downtown Manhattan. But the period from which we can draw the most useful lessons for today may be 1971—when Pearl River opened—a year of uncertainty and renewal for a diaspora shattered by geopolitical conflict, but, through cosmic historical forces, destined to come back together again.

Today, pandemic-era Chinatown remains beset with the same challenges as when Si Xin was founded: poverty, discrimination, and poor housing and labor conditions. But a generation of new activist groups is organizing in and around the enclave to rehabilitate and uplift working-class immigrant communities. The Chinatown Art Brigade protests gentrification with radical installations, CAAAV is organizing Chinatown tenants to fight exploitative landlords; other organizations (including some that Pearl River has partnered with for fundraising) are working to promote local restaurants and other small businesses that suffered during the pandemic lockdowns.

Though my father started the store without firm plans in mind, he says, “at the time, we thought it was exciting, because you start from nothing and [be] kind of a pioneer.” He thought it might last three years if they were lucky. The lucky streak has so far lasted half a century. This fall, after a year and a half of misfortune, Pearl River celebrates its 50th anniversary.

The “friendship store” is no longer a political lightning rod in Chinatown, but its survival is a testament to the enduring aspirations and contradictions that have led up to this moment in Asian American life—the fusion of enterprise, politics, and culture that anchors immigrant communities, to be replenished by each new generation that returns to locate its future in its history.