Finntown in the 1920s and 30s was a bit like a leftist fantasy mixed with a touch of “Portlandia”…

June 12, 2014

In 2007, when John Amman was deciding whether or not to buy an apartment in the Alku, a tidy, unassuming four-story brick building on a quiet block in Sunset Park, he ticked off all of the usual boxes: cost, location, proximity to the subway.

But–the most important reason came from his son.

“Basically, I bought the place because my son liked [it] so much,” Amman said.

He had no idea that his new home occupied a little-known but important piece of housing lore in New York City – that the Alku, built in 1916, is the first not-for-profit cooperative apartment building in New York City, and perhaps the entire country.

“I work for a labor union, and it was kind of serendipitous, stumbling on this place that’s like the oldest worker’s co-op,” Amman said. “So I feel a kind of visceral connection to the idea of how we do things here, that as a cooperative we make decisions together.”

He’s recounting this story as he and a few other residents of the building are working to renovate a recently-vacated ground-floor apartment in the building. Taking a break from plastering a wall, Amman said that after living in the Alku for more than seven years, he feels a “very strong sense that people own their apartments but we really own them collectively, and we all have a stake in this place, together.”

In New York City, co-ops today are more known for their strict (and some would argue overly discriminating) boards with price tags that can reach in the millions of dollars, but the origins of the cooperative housing model are actually more proletarian.

The Alku was built by a group of Finnish socialists, part of the once-vibrant Finnish community that lived in the neighborhood. But the story of this building and the dozens of Finnish-built co-ops that followed it, have largely been forgotten.

“These were all built by the Finns,” Saasto said, pointing at it and other apartment buildings down the block that encircle the park. “Whenever you had a bunch of Finns together, eventually there was a co-op of some sort.”

Robert Saasto is someone who wants to change that. “The Finns came here starting in the late 1800s, and between 1910 and 1925, the immigration flood was tremendous,” Saasto said.

A tall, rangy man with a slight, hard-to-place accent, the 66-year-old Saasto now lives in Long Island, where he’s a practicing attorney. But he grew up in Sunset Park, born to Finnish immigrant parents who moved to New York City after World War II.

He has dedicated his adult years to keeping memories of Finntown alive — and in particular, those of the co-ops where he and his extended family lived for decades.

Saasto’s standing in front of one of them, the Sunset Home Association on Seventh Avenue, its name written in tidy gold letters above the entryway.

“These were all built by the Finns,” Saasto said, pointing at it and other apartment buildings down the block that encircle the park. “Whenever you had a bunch of Finns together, eventually there was a co-op of some sort.”

To Saasto, the Alku, the Sunset Home Association, and the other Finnish co-ops that dot the neighborhood represent the lasting legacy of the Finnish in Sunset Park.

“We brought the co-ops into the United States,” he said, noting that at the time, the idea of not-for-profit cooperative housing was so new that there weren’t any laws on the books to regulate them. “We had the concept before anybody thought of it.”

The story of how the co-ops came to be is rooted in the radical politics of early Finnish immigrants.

“Everything was done for the people,” said Saasto of early Finntown residents. “I call it socialism. And that’s the way they were.”

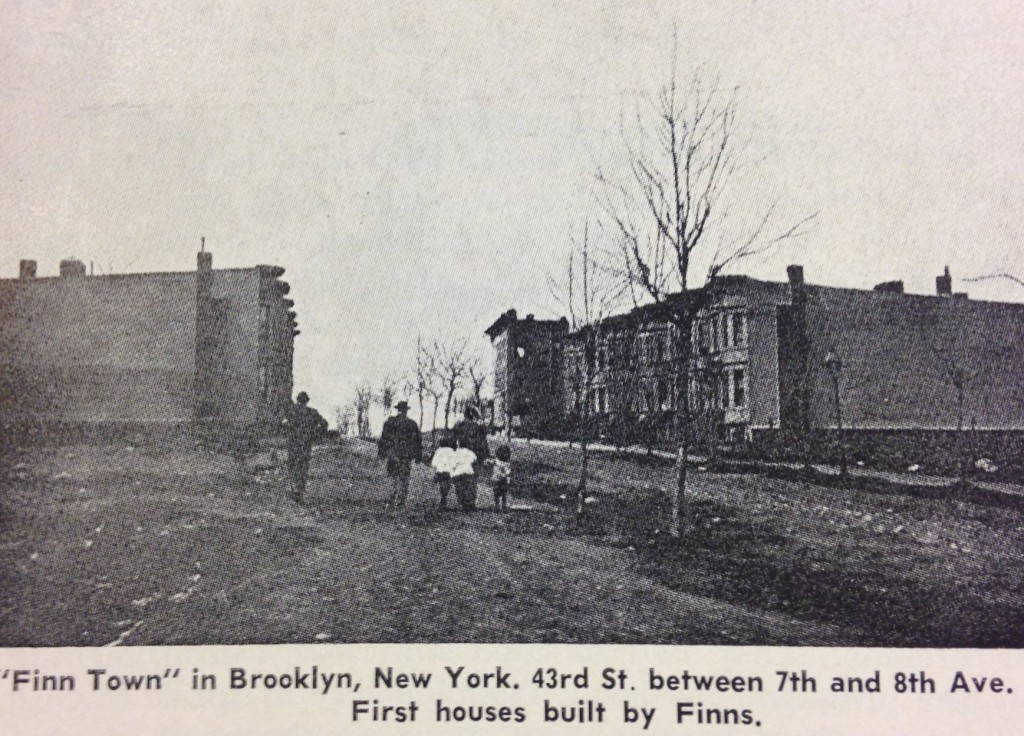

Brooklyn’s Finntown

Today, not much remains that would tip off a casual bystander to Sunset Park’s Finnish past. One block in the heavily Chinese part of the neighborhood has been renamed Finlandia Street, a small plaque tucked away in front of a Spanish-language church that commemorates its Finnish origins, and a few buildings with Finnish names, etched in the stone lintels above the entryways.

But Finntown was once a vibrant community that at its height numbered more than 10,000 residents, clustered around Eighth Avenue just south of the eponymous park that gives the neighborhood its name, living mostly in the co-ops they built.

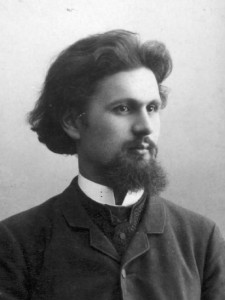

And if one person can be said to have spurred the creation of the co-ops, it would be Matti Kurikka, the charismatic editor of the Brooklyn-based New Yorkin Uutiset newspaper shortly after the turn of the 20th century, and a passionate devotee of a particular strain of utopian socialism. A leader in the growing socialist movement in Finland, he came to Sunset Park in 1909 to take the helm of the paper.

By the time Kurikka arrived, Finntown had already been firmly established — its earliest residents had come in the late 1800s, fleeing persecution from the Russian czar and lured to Sunset Park by the promise of jobs on Brooklyn’s bustling waterfront. Almost three decades later, it had become a small but burgeoning neighborhood of about 2,000 residents.

Kurikka was already well-known in Finntown as the founder of Sointula, or “Place of Harmony,” a short-lived Finnish utopian commune in British Columbia.

A fanatic in the truest sense of the word, his vision for a new world was based on the principle of co-operation, which, he wrote, “is the one that will rescue humanity by demonstrating its practical possibilities, after which people will establish new Sointulas until the world is full of them.”

As Onni Kaartinen, a leader in the Finnish American Communist Party movement, wrote in A History of Finnish American Orgs, it was Kurikka’s fiery speeches expounding on the possibilities of co-operation that sparked the discussions among Finntown residents of cooperative living.

His ideas found fertile ground, as Finntown was becoming a hotbed for radical politics, buoyed by new immigrants who, like Kurikka, had also been involved in socialist movements in Finland. There were so many, that they were simply known as “Red Finns,” said Peter Kivisto, a sociologist at Augustana College in Illinois, who has studied the history of Finnish immigration.

They practiced “a very pragmatic kind of socialism, a very bread and butter kind of socialism,” Kivisto explained.

But a small group of Finntown leftists and their families, inspired in part by Kurikka’s vision of co-operation, decided to go a different route, one that would be literally and figuratively groundbreaking.

Other working-class communities in the turbulent years before and during World War I went on rent strike and burned effigies of their landlords to protest poor living conditions and exorbitant rents.

But a small group of Finntown leftists and their families, inspired in part by Kurikka’s vision of co-operation, decided to go a different route, one that would be literally and figuratively groundbreaking. They would build their own homes instead, based on a cooperative model where ownership would be shared equally among all the residents, with the goal being not profit, but affordable housing.

According to Katri Ekman, a former resident of Finntown and a co-author of A History of Finnish American Organizations in Greater New York, the idea of the co-ops in Sunset Park originated with the Brooklyn Finnish Socialist Club and its members over evening conversations at their storefront on Eighth Avenue.

From those conversations came a plan: an initial group of six families each chipped in $500 (almost $11,000 in today’s dollars); $12,000 was borrowed from other neighborhood residents in the form of what were known as “comrade loans”; and the remaining $25,000 they needed came in the form of a bank loan they would repay over the years.

The Alku and Alku Toinen were a revelation..these Finnish-built cooperatives boasted five rooms each, modern conveniences like hot water, showers, and gas stoves, and decorative touches like marble window sills.

The families themselves quickly set to work on building what would become the Alku, or “New Beginning.” In 1916, the Alku was completed, followed shortly after by the Alku Toinen — more than a decade before the Amalgamated Clothing Workers Union built in 1927 what is commonly (and mistakenly) referred to as the first not-for-profit cooperative housing built in New York City.

The Alku and Alku Toinen were a revelation — at a time when most working-class families were crowded into tenements often lacking even the basics in sanitation, these Finnish-built cooperatives boasted five rooms each, modern conveniences like hot water, showers, and gas stoves, and decorative touches like marble window sills.

People from outside of Finntown marveled at the two buildings and the fact that working-class families could own their own home. In 1919, a New York Tribune reporter, Inis Weed, wrote of the two co-ops, “A family on a day’s wages owning the apartment in which it lives? But seeing is believing. There they stand, two four-story brick apartment houses, with attractive entrances, wide groups of windows, and areas affording a flood of light for every room” – and all for $27 a month.

Leaders in the housing movement took note, and the Finnish became widely recognized as pioneers in the cooperative movement in New York City…

Encouraged by the success of the Alku and the Alku Toinen, other apartment buildings built along the cooperative model quickly followed. By 1927, a little more than a decade later, there were almost 30 Finnish-owned co-op buildings in Sunset Park, with maintenance costs that were less than half of the rent of apartments in privately owned buildings.

Leaders in the housing movement took note, and the Finnish became widely recognized as pioneers in the cooperative movement in New York City, with government officials pointing to the apartments they built as models of working-class housing.

“Why is it that the Finns can put up houses on the cooperative plan and we cannot?” asked Clarence Stein, Chairman of the State Commission on Housing and Regional Planning, in 1924.

And in 1937, New York City Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia praised the Finnish, writing, “If more would follow your example, the problem of slum clearance could be solved more speedily and decent housing conditions could be provided for all people.”

Encouraged by the success of the housing they built, members of the Finnish Socialist Club applied the co-op model to other businesses, starting a cooperative bakery at 43rd and Eighth Avenue. The bakery was followed by a restaurant, meat market, grocery store, and even a poolroom and mechanics garage, all on the same five blocks on Eighth Avenue. With thousands of members, they did brisk business – in 1922, it was reported by the US Department of Labor that in total, they had revenues of $260,000, the equivalent of $4 million today.

Finntown in the 1920s and 30s sounds a bit like a leftist fantasy mixed with a touch of “Portlandia:” a host of cooperative, member-owned businesses lining Eighth Avenue, where residents could buy their daily necessities of milk, bread, and meat, and dozens of co-op apartments that were the luxury condos of their day, built by and for working-class immigrants.

The socialist dream that a New York activist from the time wrote about – “production for use, not profit,” as “co-ops of America take over more and more of the means of production” – was being realized in Finntown, and the co-op apartments were its most envied and emulated manifestation.

A Neighborhood in Decline

82-year-old Mauno Laurila belongs to the last generation that remembers Finntown as it once was. Immigrating to the US in 1950 at the age of 18, he landed initially in Harlem, which at the time had the second-largest Finnish community in New York City. He eventually made his way to Sunset Park after serving with the US military during the Korean War.

While the community had already shrunk from its height during the period between the two world wars, in Laurila’s memory, the neighborhood was still bustling, and the co-ops were still full of Finnish residents.

“It was a good, safe place to live. At that time, we felt like we had our own city there, in Brooklyn,” Laurila reminisced over the phone. “It was a very close-knit community. You heard Finnish spoken on the street corner, everyone knew each other.”

He and his family lived in a co-op building bordering the park that was known colloquially as the Sweatdrop — “It was one of the last ones, so they really sweated to build it,” Laurila joked — and became heavily involved in the life of Finntown. Laurila joined the board of the Imatra Society, a three-story community center complete with a bar and sauna, that hosted lively dances, theater performances, and dinners.

“There was always a lot of things going on. Different organizations had their meetings there. There was the Finnish male chorus. In mid-summer, we had bonfires there. It was always full of people. He also became president of the Uutiset newspaper, where his wife Anja also worked as a typesetter and columnist.

In 1929, the US tightened immigration from Finland, restricting new immigrants to less than 600 per year; this coincided with the Great Depression, forcing many to leave Brooklyn to look for work elsewhere.

But the seeds of Finntown’s decline had already been sown decades earlier, portending its eventual end. In 1929, the US tightened immigration from Finland, restricting new immigrants to less than 600 per year; this coincided with the Great Depression, forcing many to leave Brooklyn to look for work elsewhere. Internal divisions and government repression began weakening the Finnish left (and the left in the US in general). The cooperative businesses were gone by the time Laurila moved to the neighborhood, as post-war economic shifts forced them out of operation, unable to compete with the rise of chain stores and mass production.

By the 1970s, Finnish churches had sold their buildings and land to others, more businesses had closed, and Finnish residents, like many white New Yorkers, were continuing to flee Sunset Park and the city for the suburbs of Long Island, New Jersey, and elsewhere.

“Brooklyn’s Finntown [is] losing its flavor,” proclaimed a headline in the New York Times in 1972, which estimated that there were only 1,500 Finnish Americans left in Sunset Park…

“All the young people moved out, so I saw it coming,” Laurila said. In 1991, he and his wife also left the co-ops and Finntown, moving to Connecticut.

Outsiders also noted that Finntown was a neighborhood in decline. “Brooklyn’s Finntown [is] losing its flavor,” proclaimed a headline in the New York Times in 1972, which estimated that there were only 1,500 Finnish Americans left in Sunset Park, most of whom were elderly single women and widows living in the co-op apartments. The closing bell for Finntown came in 1997, when Imatra Hall was sold.

It had fallen into debt, and its membership had dwindled. Fati Svahn, the then-president of the New York Uutiset, estimated to a reporter in 1996 that there were only 100 Finnish families left in the neighborhood. Even the Finnish government, which had buoyed the coffers of the Imatra Society through its lean times, declined to give money to keep it afloat, with the Consul General of Finland saying that “it has fulfilled the task that it started.”

Saasto, by then the president of the Imatra Society board, led the effort to sell the building.

“The old timers wanted to keep it. The old people were like, we have to continue sisu, it’s a Finnish word, meaning ‘hold on against all odds,’” he said. “I became the guy who was mediating a lot, and eventually they got enough people to agree to sell it. It was a battle.”

By the mid-90s, what was once Finntown was already being called Brooklyn’s Chinatown, its bakeries now selling pineapple buns rather than korpus.

With no new immigrants from Finland coming in to give fresh life to the neighborhood, Finntown continued to fade away, leaving behind vacant apartment buildings and storefronts.

Mary Gallagher, who bought an apartment in the Alku in 1980, is someone who remembers that time.

“Oh, it looked like a holy horror. It was really a disaster area!” she said, describing the neighborhood when she first moved in.

“Eighth Avenue was very rundown, all the Scandinavians, the old ones passed away and the young ones moved away,” she recalled, a hint of her native Ireland still in her voice. “Especially the stores, they were locked up, closed up. The business was gone. It took it a few years for it to really, really come back.”

New immigration did eventually breathe life to Sunset Park and Eighth Avenue. A wave of Puerto Rican residents had already moved to the western portion of the neighborhood in the 70s; on their heels then came the newer immigrants who moved to New York after the 1965 immigration reforms lifted restrictions on Asian and Latin American countries, residents that dominate the neighborhood today.

By the mid-90s, what was once Finntown was already being called Brooklyn’s Chinatown, its bakeries now selling pineapple buns rather than korpus.

“There was a sauna here. My parents went there. There was a tailor, a cleaner,” he remembered. He shook his head. “It’s all gone now.”

“This was all Finns,” Saasto said, standing at the corner of 40th Street and Eighth Avenue. He’s pointing out where Finnish businesses used to be, storefronts that now cater to a mostly Chinese clientele — a video game retailer, an awning and sign company, a real estate broker’s office with listings spelled out in Chinese characters.

“There was a sauna here. My parents went there. There was a tailor, a cleaner,” he remembered.

He shook his head. “It’s all gone now.”

However, the coops they built remain. And, at least for the Alku, its legacy as not-for-profit housing is just that, a legacy. While the Alku still operates as a co-op, there are no longer any restrictions on how much residents can sell their apartments for.

And recent sales prices reflect this: according to property records, one apartment in the Alku sold for $230,000 in 2005; eight years later in 2013, two others sold for more.

Their history, too, has now become a selling point with real estate agents. According to Amman, “People who are coming in and buying are increasingly realizing the history of the co-op. The last few buyers knew that this was the oldest co-op in the country.”