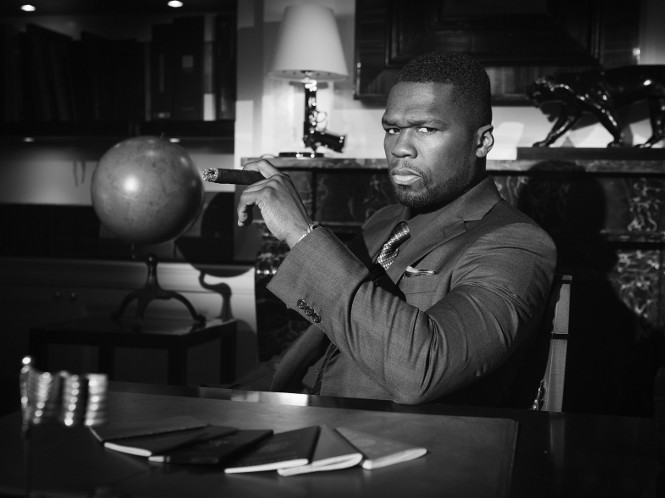

In a way, Curtis Jackson is a link to the era of black American immigration to South Jamaica, the violence that befell those who came, and the strange marriage of drugs and music that followed. He may be the last.

October 16, 2012

I am riding my bicycle through South Jamaica, Queens, searching for places where 50 Cent hustled. On Rockaway Boulevard, I glide through red lights, past the small West Indian restaurants and Bangladeshi clothing stores. I stop at 145-40, where, in 1998, police executed a search warrant for a young Curtis Jackson at the flophouse where he had a room. Now renovated and available for rent, it bears no sign of ever being a residential building. To the right is a 99 cent store; two stores down to the left the Tax Sister advertises her services. A middle-aged black couple walks slowly down the block towards me. The woman’s hair, gelled to her head, is shiny. The man, eating potato chips, fills out a wide black t-shirt. His beard is unruly. I ask them if they are surprised 50 Cent was arrested here. “Well, they say he was from around here,” she murmurs. Her partner, still munching, stops momentarily as if he is going to speak, but doesn’t. As a parting question, I ask them if things have changed around here. “Sure have!” interrupts a limping passerby who has caught the last of our exchange. The three of them continue down the block.

I end up on 135th Avenue and Guy R. Brewer Boulevard, across from Rochdale Village, a set of private apartment buildings easily mistaken for projects. This is the block he raps the most about. In his autobiography, From Pieces To Weight: Once Upon A Time In Southside Queens, he describes what happened here after he left a drug rehabilitation program: “On the first day of leave, I was back on Guy R. Brewer Boulevard—back on the strip.” In 2001, after surviving nine shots and sudden abandonment by his record label, he defiantly released his own mix tape, Guess Who’s Back. In the intro he raps “in six months, I sold a million gold tops [crack] on Guy Brew.” Two high school girls slap box at the bus stop. The Chinese food joint and the dry cleaners each have a few customers. An aging blue van is parked with its door open. A doughy man in a blue shirt and trucker hat sits inside the van playing chess with someone seated on a crate on the curb. A folding table is between them. I approach the chess crowd on my bicycle. Save the warbled reggae trailing Jamaican dollar vans that race the avenue, there is no music playing. No addicts or sellers are visible. There is also no vibrancy. For better or for worse, the nineties are definitely over.

From Boo-Boo To 50

Before Curtis Jackson III became 50 Cent—a rap artist whose debut album sold more than ten million records—everyone called him Boo-Boo. His mother Sabrina was fifteen when she gave birth to him in 1975. Brina, as she was known, sold drugs from an apartment on Old South Road in South Jamaica, Queens, to support him. At age twenty-three, Brina was murdered, and Boo-Boo found himself under the care of his grandparents. He was told his mom would not be coming home.

Competing with others in the house, Boo-Boo often got the short end of the stick. “My sneakers would be torn, my clothes dirty, and my skin ashy,” he penned in his autobiography. At weekend parties, his drunken uncles would send the chubby eleven-year-old to pick up Fat Alberts—cocaine packed in tinfoil. Deprived of attention and in such close proximity to drugs, he surreptitiously began selling cocaine to his uncles himself.

In 1988, rookie policeman Edward Byrne was killed in cold blood in South Jamaica while guarding a witness. It became national news. Overnight, the police swept down on the neighborhood searching for hit men associated with Fat Cat, the local Godfather. Their presence temporarily shut down the open-air drug market. Curtis watched as hustlers adjusted, increasing the sophistication and strategy in their sales. He learned quick: “If the ‘hood was cocaine, then the rookie cop’s murder was like baking soda. And an angry police force was the fire that cooked up new hustlers. Hustlers like me.” Slowly, he was able to buy a motorcycle, and then a car. It began to seem like a career.

At age nineteen, life began to catch up with him. He was arrested twice in two weeks for crack sales. He then learned from his grandmother that his mother had been murdered. Soon after that, his girlfriend became pregnant. The thought that he could succumb to the streets—as his mother did—and leave his child unprotected, forced him to take stock. “I wanted to be there to be a part of child’s life,” he writes. Inspired by hustler-turned-star Notorious B.I.G, Jackson looked to rap as an escape route. Using the name 50 Cent—the moniker of a brazen, deceased Brooklyn stick-up kid —he befriended Queens hip-hop legend Jam Master Jay. Jay helped him move from his clever freestyles to songs with structure. He landed 50 a guest appearance on an early Onyx record, and eventually got him a record deal through Sony.

The Shooting

His first solo release was the provocative but comical “How To Rob,” in which he imagines himself robbing successful rappers. Other songs soon leaked, including “Ghetto Qu’ran.” It seemed like his exit plan was working. What he hadn’t considered was how dangerous public persona could be. On May 24, 2000, while Jackson was in a car in front of his grandmother’s house, a stranger approached him from behind and started shooting at close range. He was hit nine times. Jackson drove himself to Jamaica Hospital, narrowly escaping death: one bullet knocked out a tooth; another hit his hip. He would forever slur and limp.

The media speculated that the shooting was connected to “How To Rob”—rivals Wu-Tang Clan and Big Pun had issued threats in response. In his autobiography, Jackson is deflective, suggesting that the shooting was linked to his days dealing dope. “The situation with those shots going off didn’t have anything to do with hip-hop.” According to Ethan Brown, author of Queens Reigns Supreme: Fat Cat, 50 Cent and the Rise of the Hip-Hop Hustler (2005)—an unprecedented study of the connection between eighties drug traffickers and Queens rap stars—the trouble was over “Ghetto Qu’ran.” In it, 50 exposed the South Jamaica cocaine underworld of his childhood, naming names and adding more than his two cents.

Today, remnants of that deadly underworld exist as quiet corners. At night, on South Road and 150th Street, young prostitutes weave in and out of the shadows. The daylight reveals a block of closed businesses, including a defaced funeral parlor. On Sutphin Boulevard and 116th Avenue, ranch-style houses fit snugly together on narrow streets. Retirees idle against cars, and crabapple trees nod sleepily into traffic. Nearby, towering housing projects emerge like a short range of red hills, encircled by dozens of police cameras. If cocaine trafficking continues, it does so indoors.

Supreme Team and Fat Cat

During Jackson’s early teens, however, New York convulsed with spasms of unchecked violence. South Jamaica, then home to one of the most ruthless and cash-rich gangs, was a neighborhood where drugs and guns were openly brandished and millions of dollars collected. For Lorenzo “Fat Cat” Nicholas, the Godfather of South Jamaica, the now-deserted two-story building on 150th Street once functioned as headquarters. His elderly mother held court there, moving millions in heroin and cocaine. The Supreme Team, run by Kenneth “Supreme” McGriff (or ‘Preme), was Cat’s major muscle on the street. They lorded over Baisley Housing Projects and controlled crack distribution in developments across Queens, including Queensbridge Houses in Long Island City. Brina, Jackson’s mother, sold drugs independently near Fat Cat’s building. [She never sought Cat’s protection: a brave—and perhaps fatal—choice.]

The Supreme Team crew was ruthless. They killed dozens—rivals, wayward members, and lucrative suppliers—including four Colombian suppliers who were lured into Baisley and bludgeoned to death. They were sloppy and took little care to hide their tracks. Fat Cat was ultimately arrested in the backroom of his headquarters, surrounded by guns; Supreme at his cream-colored vinyl-sided stash spot on 116th Avenue, his face covered in the cocaine he was trying to flush.

With Fat Cat and ‘Preme knocked down, it was only a matter of time before the Supreme Team crew dissolved. However their legacy—of swagger, wealth, and power—continued to make an impression on a generation of black children whose parents had left oppressive conditions in the South for a difficult New York. Nasir Jones aka Nas, the iconic rapper from Queensbridge Houses, belonged to said generation. On “Memory Lane,” a cut from his 1993 debut album Illmatic, he raps:

I hung around the older crews while they sling smack to dingbats

They spoke of Fat Cat/ that nigga’s name made bell rings, black

Some fiends scream/ about Supreme Team/ a Jamaica Queens thing

Uptown was Alpo, son/ heard he was kingpin, yo.

But it was 50 Cent, perhaps because of his South Jamaica roots and his mother’s involvement with drugs, whose musical career became most embroiled in the legacy of the cocaine eighties. As a teen he had trained at a gym run by Black Just, a Supreme Team member, and he watched Team members run Baisley, near where he himself sold crack. By this time Supreme was already locked up and his violent nephew, Gerald “Prince” Miller, ruled. A decade later, 50 wrote about those years in “Ghetto Qu’ran.”

When you hear talk of the Southside you hear talk of the team/

See niggas feared Prince and respected ‘Preme/

For you slow motherfuckers Imma break it down iller/

see ‘Preme was the businessman and Prince was the killer.

Back on the street after a long stint in Elmira State Prison, Supreme had allied himself with 50’s music rivals Murder Inc. He felt 50’s lyrics tarnished and diminished him, and it has been alleged that he ordered the hit. In his autobiography, My Infamous Life, Prodigy of Mobb Deep states without hesitation, “Preme…got 50 shot up”—adding, “fuck Supreme.”

It is difficult to piece together an exact history from the different narratives. Even though Brown chased down court documents to build his case in Queens Reigns Supreme, he was dismissed by 50 Cent, who said “the writer ain’t in South Jamaica, Queens…he don’t understand nothing he talking about.” Predictably, others have challenged 50’s version of events.

South Jamaica and the Great Migration

The code of honor would persist and deeply influence all those who lived in Edgefield. Honor, along with violence, was part of the region’s heritage.

—All God’s Children, Fox Butterfield

Friction between a rising rap superstar and fading coke don might now seem strange, but it arose from two different neighborhood eras colliding. During the Great Migration, African Americans who came to South Jamaica—harshly described by author Ethan Brown as a “lower class hell”—found few opportunities in an area already marked as poor, and black. Some early arrivals found some city jobs (both ‘Preme and Fat Cat’s parents were MTA workers) but by the early eighties, many had been driven into the drug trade. After a decade-and-a-half, the unsustainable, cannibalistic business of sacrificing one portion of a community to feed another had exhausted itself. The rap business had matured, and Queens groups like the Lost Boyz, Mobb Deep, and Capone-n-Noreaga dug deep into the stories and tragedies of the guns and cocaine era to fashion their music.

Queens was a tertiary destination for Southern migrants. “People [migrated] from places like Florida, South Carolina, and Georgia, with some from Alabama. Migrants would have first moved to Harlem, and later to central Brooklyn. When that got too crowded, or when families accumulated enough means, they eventually relocated to Queens and Long Island to escape the overcrowding,” says Josh Guild, professor of history and black studies at Princeton University. South Jamaica, however, offered none of the hope of nearby Hollis or Long Island.

Although hip-hop aesthetics did much to mask the southern roots of its progenitors—such as adopting European sneaker brands and Black Muslim numerology (“It’s about the modern,” says Guild)—neighborhoods like Jamaica retained much of the migrant character. Even now, small-town churches protrude from buildings, nestle in corners, and emerge from unexpected places along Sutphin Boulevard. Restaurants serving “South Carolina style” can still be found. 50 Cent often used slang and drawl that comported with his Southern competitors. In the introduction to his VH1 special “The Origin of Me”, he tells his grandmother: “When I be talking sometime I use South Carolina slang… I get that from you.”

Even the urban, northern violence of the eighties had its origins in the hyper-violent world of the nineteenth-century South—the white South. In All God’s Children (1995), Pulitzer-prize winning author Fox Butterfield traces the lineage of Willie Bosket, considered the most violent prisoner in the New York correctional system (Bosket committed 200 crimes, including several murders, before he was fifteen). Butterfield discovers that Willie’s black ancestors lived in Edgefield, South Carolina, known then as “bloody Edgefield.” There, the white population murdered each other at astonishing rates, in gun duels and surprise attacks. After Emancipation, they terrorized blacks to maintain their social position. Willie’s ancestors took up guns to defend themselves against this threat, then kept their guns as a way of life. Bosket’s great-grandfather, Pud reportedly said to a foe he trounced, “Don’t step on my reputation. My name is all I got, so I got to keep it.”

The connection to the bloody conflicts in South Jamaica a century later is more than theoretical. Fat Cat and his enforcer Pappy Mason were born in Alabama. In “The Origin of Me,” when 50 returns to his grandmother’s ancestral home to search out his roots, he goes to Edgefield—the same small and hyper-violent South Carolina town Butterfield studied.

The struggle between 50 and Supreme—who himself had begun to produce music—was a struggle for the control of a new economy; between a don who wanted to tell stories, and the storyteller who would become don. In a way, 50 is a link to the era of black American migration to South Jamaica, the violence that befell those who came, and the strange marriage of drugs and music that followed. He may be the last.

The Last Link

Back on my bicycle, I am circling home on Guy R. Brewer, the main boulevard in South Jamaica, Queens. I notice that the African American presence in South Jamaica seems to be receding. Newer storefronts are continental African, Jamaican, Latino, and Guyanese. A robed family gathers in the yard of a house, dancing to unfamiliar music. As I veer onto a back road, I encounter Sikh workers crouched in the hot sun, renovating an unfinished house. “It is not anecdotal,” says Guild. “The descendants of African Americans who came primarily from places like the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida are going back.” Some made it out, others succumbed; but for the many who moved here, rising costs associated with redevelopment, stagnation, and continued police harassment are making other locations more attractive.

50 made it out. He lives in Connecticut in a mansion formerly owned by Mike Tyson. After his shooting, he partnered with Eminem. They used his near-death experience and sense of humor to create a story millions bought. It is an amazing story, made more so by the humorless, unstable streets of his teens.

I end up on 150th Street, and make one last stop across the street from Fat Cat’s old lair. The shuttered building has been long asleep, but leaning on my handlebars, I try to imagine the scene here in 1985. A swirl of frail addicts and hungry dealers dressed in corduroy and flaring pants; Fat Cat’s mom leaving to go home to Ozone Park after a long day; dreadlocked Pappy Mason, hand on his gun, seething as he watches his boss being led away by police. On his way to Brina’s apartment, Boo-Boo would have passed here.

For a moment, I glimpse the intense world 50 Cent drew so heavily upon, that infused his music and shaped him. But South Jamaica has changed, and so has hip-hop. The 2007 conviction and life sentence of Kenneth “Supreme” McGriff for (amongst other things) the murder of rapper Eric “E Money Bags” Smith was the final act in an extended drama of cocaine and hip-hop in Queens; the final, bloody nail in that coffin.

Perhaps, in the future, the rhymes out of South Jamaica will be from children of immigrants, like Nicki Minaj (born Onika Maraj), the superstar whose family arrived from Trinidad in 1987, when she was five. Although her music incorporates dance and reggae—and avoids crime references—she represents her neighborhood fiercely (“grew up in Baisley/ South Jamaica, Queens and it’s crazy” she raps in “Moment for Life”).

As African Americans families from Queens leave New York, the stories and styles that flourished in South Jamaica might appear elsewhere, in new incarnations. Waka Flocka Flame, a young rap star from Atlanta, reminds interviewers that he was born in Queens in 1986. He left for Georgia in fifth grade. “Y’all know ya’ll my kin folk…back down to Baisley projects” he raps to 50 Cent in “Keep It Real.” Bimmy, a former lieutenant in the Supreme Team, is Flocka’s uncle.

At the beginning of “Ghetto Qu’ran,” 50 asks a rhetorical question, “What y’all niggas know about the dirty South?” He is preparing the listener; a subaltern history of South Jamaica is to follow. He names kingpins and victims and chronicles heroism and betrayal. His awareness of his Southern roots, his close proximity to the Supreme Team, and his unexpected rise and redemption in the Queens hip-hop scene imbue both his writings and his music with significance beyond their immense commercial value. Even as the community changes, it will be his poetry and memories against which people will compare the stories; his lyrics against which they—as author Ethan Brown does—will compare the official facts.

In front of Fat Cat’s deadened headquarters, enveloped by three decades of forgotten history, I think of some of his other lyrics, this time, from “Many Men”:

I’m the diamond in the dirt/ and I ain’t been found

I’m the underground king/and I ain’t been crowned

When I rhyme/ something special happen every time.

Because of these special rhymes, we know much more about the “dirty South.” We know about the complex forces at play; we know about those who failed; and we know about those—like him—who succeeded in the crucible of South Jamaica.

Read more on Open City: Queens Stand Up: The Essential Reading Guide on Hip-Hop’s Forgotten Borough