“To occupy this space, this body, is disorienting and at times disturbing, because you are never quite sure whose gaze truly sees you beyond the projections and assumptions and desires.”

January 16, 2019

“No [onscreen] lovers can ever marry me,” says Anna May Wong, the first Chinese American star in Hollywood, when interviewed in Movie Classic in 1931. Speaking baldly on the tacitly enforced prohibition against interracial romance in films at the time, Wong also draws attention to the double injury of losing leading roles to white actors in yellowface: “If they got an American actress to slant her eyes and eyebrows and wear a stiff black wig and dress in Chinese culture, it would be allright. But me? I am really Chinese. So I must always die in the movies, so that the white girl with the yellow hair may get the man.” Here, Wong acknowledges in rather stinging terms her own compromised position in Hollywood’s cultural production of American orientalism, along with the contradictions inherent in the silver screen’s racial imaginary: as a Chinese American woman, she embodies both the eroticized and exoticized object of male desire and the white distrust of the inassimilable Oriental other. Indeed, for much of her film career, Wong took on supporting roles as foreign seductresses, dragon ladies, and mistresses onto which Hollywood mapped its attitudes and appetites for racial difference.

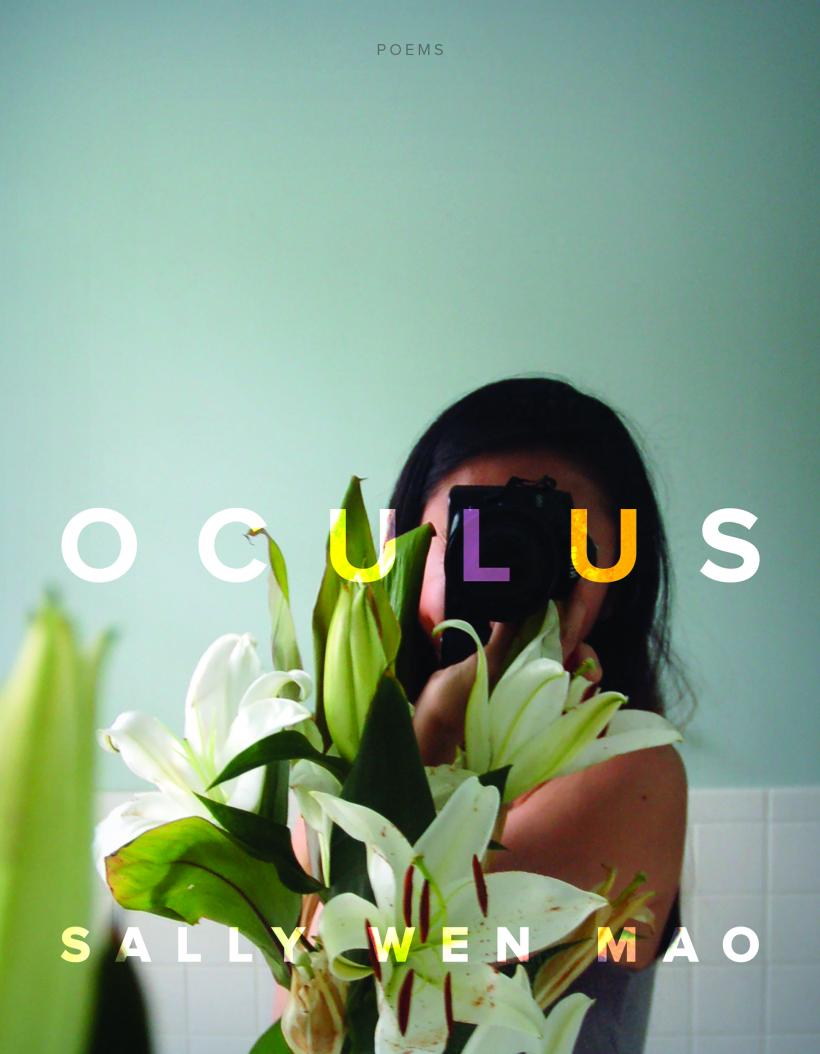

In Sally Wen Mao’s electrifying second poetry collection, Oculus (Graywolf, 2019), Anna May Wong, along with other historical and fictional women of color, is resurrected and recast to startling effect. In poems that show Wong time-traveling and inhabiting a spectrum of filmic and real life roles, Mao gives vivid voice to the woman behind the flattened stock figures on the Hollywood screen. In doing so, Mao turns a keen eye toward the strictures of representation, the construction of whiteness, and the destabilizing pleasures of shape-shifting. The Anna May Wong poems form a spine for Oculus, but elsewhere in this tightly cohesive collection, poems meditate on the constraints of visibility and the psychic costs of spectatorship in formally inventive and linguistically wild ways. Marvelous, too, is the velocity of time travel and the quicksilver swerves between cultural references in these poems—Mao shuttles us from Afong Moy to Janelle Monae to visions of a cyborg future in a matter of a few pages, and in each case, resists and reverses the oppressive gazes women of color have long been subject to and felt constrained by. “In this life I have worshipped so many lies. / Then I workshop them, make them better, ” declares the speaker in the poem “Occidentalism,” early on in the collection. In Oculus, Mao has workshopped and revitalized the ways we think about visibility and its inverse, along with the mercurial self and its embodiments.

—Jenny Xie

Read an excerpt from Oculus, “The Diary of Afong Moy” on The Margins.

Jenny Xie

Reading Oculus, I was arrested by the poems’ treatment of what it means to be embodied—especially what it means to inhabit a racialized and feminine body—and the brutal constraints of being caught in someone else’s line of sight. These poems meditate strikingly on the burdens of being beheld, of existing as spectacle and fetish object, and of having one’s life unfold publicly. At the same time, Oculus takes up the historical invisibility and muteness of the Asian American body, along with the paucity of visual narratives afforded to it. Can you speak a little to the tension between the spectrums of visibility in the book?

Sally Wen Mao

You describe it perfectly—in the American context, the racialized feminine Asian body is both a spectacle and an absence, coveted and reviled at the same time. The duality of this has always interested me: Asian women’s bodies, and marginalized bodies in general, have always existed at the intersection of attraction and revulsion. Afong Moy, the first Asian woman to arrive on American soil in 1834, was described as both a fairy and a freak when she was displayed in an exhibition literally among Oriental objects to a paying white audience of spectators. And when she disappeared from the picture, it was only because the advertisers wanted to bring another Asian woman from Canton to display again—so in that sense, there was room only for one person to be the “visible” one. The reality is that representation always implies a kind of invisibility, muteness.

To occupy this space, this body, is disorienting and at times disturbing, because you are never quite sure whose gaze you can trust, whose gaze truly sees you beyond the projections and assumptions and desires. You’re not even sure you can trust your own desire, because you wonder how much of that is an internalization of all your deficiencies and failures to conform to someone else’s fantasies.

In Oculus, I try to break down and respond to the visual narratives that do exist—as I’m sure you know, these narratives are incredibly limited. The paucity of visual narratives only cast a sharper edge on what exists, which is a very salacious and demented distortion—in some cases, complete fabrication—of actual Asian and Asian American women’s lives.

JX

I agree that representation “implies a kind of invisibility, muteness.” In the poems from the book that take on the personas of Afong Moy and Anna May Wong, we see representation both circumscribes agency and allows for a demonstration of it. From the disfigurements of representation—the flattening of Moy into a display object and Wong into stock roles of Chinese seductresses and dragon ladies—you draw the energy to reanimate, reclaim, and reimagine. The poems re-narrate the experiences of these women, in some sense, or speculate as to what their trajectories and stories could have been. What was the process behind writing from these voices? What kind of research did you engage in, and how did you settle on the timbre and tone of their voices?

SWM

Both Afong Moy and Anna May Wong came into the spotlight in America while in their teens, and their narratives were very much controlled by white people. Separated by nearly a century, Afong Moy came to the U.S. at the age of 19 in 1834 and Anna May Wong starred in her first film at 17 years old in 1922. Anna May Wong may have had a little more agency–in my research I found a lot of first-person material from Anna May Wong, who was outspoken and charismatic. Her medium was also film, some of which I can access and watch, while Afong Moy was a human exhibition, inherently ephemeral.

There are no first-person research materials on Afong Moy. Every record of Afong Moy is from the perspective of a white person looking at her. This dynamic interests me: when researching, I was keenly aware of a white male gaze that controls the image of these women, in essence subduing their voices and their stories. Anna May Wong enacted the Orientalist fantasies of many white male directors, and Afong Moy was an Oriental spectacle literally sold for consumption, hired by a pair of American merchant brothers. For so long, white people have been unapologetically misrepresenting and capitalizing on the lives and experiences of “others,” and this authority is not questioned. In translating my research to the poems, I deliberately considered what it actually meant for these women to be token bodies placed on display for a rapt audience who at the same time actively discriminated against them. For Anna May Wong’s voice, I looked through old columns she wrote for the New York Herald Tribune and biographies, and wrote the poems from there.

Afong Moy’s voice was imagined on my part, so I took the facts (for example, she was pressured to show her bare bound feet against her wishes) and constructed a voice from these records. In the newspaper stories that described her, her otherness was so emphasized that no one considered what her perspective may have been, how she processed whiteness. I tried to reframe it so that the whiteness becomes just as much of a spectacle—in the poems she is aware she is being looked at, but she is also observing. Both Afong Moy and Anna May Wong had to navigate the border between pride and humiliation, the emotions that arise from being the objects of fascination, desire, and dehumanization. I think this is not so different from the experiences of contemporary Asian American women, whose experiences have been impacted by stereotypes that formed over history and time. The context of this history is important, and so I hope my poems have excavated this.

JX

I love hearing about your process behind constructing the Afong Moy and Anna May Wong sequences, which are some of my favorites from the book. I think the reversal you stage, of reframing their stories to underscore whiteness as spectacle, comes across brilliantly. Can I ask what went into your decision to voice these poems from the first-person? You address many historical and cultural figures in this book—Nam June Paik, Ruan Lingyu, Faye Valentine from Cowboy Bebop—but some of these other poems (“Provenance: A Vivisection,” “Dirge with Cutlery and Furs,” “The Death of Ruan Lingyu”) take on the second-person perspective—another intimate vantage point. Why first-person for some, and second or third person for others?

SWM

Using the first person to take on the voice of a historical figure or anyone else beyond the immediate self is audacious, and it carries responsibility. A persona poem is a way to funnel the author’s own emotions into another experience, another vessel, in order to achieve some kind of communion. I don’t always need to use persona. The second person allows me to have more direct or imagined conversation with my subjects, imagine some kind of interaction across time, space, possibility. I try to be deliberate about which poems use the first person and which poems don’t, so I’m careful with choosing these voices. An earlier draft of the poem “No Resolution” used to be in first person from the perspective of the subject, who experienced a tragedy, but I decided to change it to third person from my perspective, and that to me felt like the most honest way of examining a difficult situation or emotion that I haven’t experienced before. With the third person, I can acknowledge the delicateness of her human experience and forge a connection.

JX

Speaking of forging connections, many of these poems feel like correspondences with women—historical and fictional—whom you feel affinity with, or appear to claim kinship with. I was moved, too, by the book’s dedication (“to all my sisters”). I’m curious how a sense of audience, even if it’s just an audience of one, enters into your process. Does it?

SWM

A sense of audience does enter the process. Many of us, women of color especially, don’t feel truly seen on a day-to-day basis. That aloneness can be debilitating. I know many women who struggle but feel the need to put on a “face” that is more acceptable or palatable and accept their dehumanization as the norm. In a sense, the book’s resistance to the white heteropatriarchal gaze is to transform the gaze and turn it back to ourselves, an inward, empathetic look at the self. In that sense, “sisters” applies to any marginalized person who has felt this struggle of hypervisibility and invisibility, anyone who has grappled with and suffered from the desire to be seen.

JX

I feel many poems in the book map out the intersections between the white heteropatriarchal gaze, the Oriental other, and the glassy eye of the camera, the live-feed video-cam, or the screen. In what ways were you thinking about spectatorship in this book, which is bound up in the performance of a self?

SWM

Yes, it’s a tricky boundary between spectacle and image. The former implies exploitation, being the unwilling object of a gaze, and the latter implies self-presentation, a performance of self. The image is a familiar obsession that predates social media. The ambiguity when the performance of self becomes self-destructive, or when performance of self becomes pathological. That gray area interests me as a poet because it’s so wrapped up in everyday life now that it’s almost mundane. So much of this performance is tied to feelings of worth and value; in essence, it becomes ongoing, an entire existence all on its own—an online presence, an uninterrupted performance of self. No one knows what is truly authentic, or how to define that anymore, and this interests me. When and how does the image truly affirm? Is it possible to represent the self at all?

JX

What is the vision of the future in this book, if there’s a coherent vision? I found the technocultural threads wondrous—robots, cyborgs, mutant odalisques, teledildonics!—especially as they contrasted with long gazes into the historical past.

SWM

I’m not sure if there is a coherent vision of the future in this book, other than a kind of foolish, guarded hope that somehow technology doesn’t fail us, that we are truly progressing, we don’t fail ourselves or each other. That somehow the traumas and wounds we seek to seal with personas (robots, cyborgs, social media) are healed in some way. In a way, perhaps it’s actually bleak, and the book argues that nothing has healed yet—and these old histories are dredged up because as women of color, we still experience their aftershocks, generations later. But the foolish hope is that perhaps if we truly take a step back, and look at ourselves, stripped of noise or performance or misgivings, we can hold each other in the light. That somehow, we can recognize each other as whole human beings, whose flaws and sorrows are valid, and dream up a better future together.