As pure Tibetans, they seem to have a more direct connection to whatever their cause is…But in my case, I would be there thinking, I don’t have the genuine drive in a way. I was supporting the cause, but at the same time, I saw myself differently.

October 8, 2013

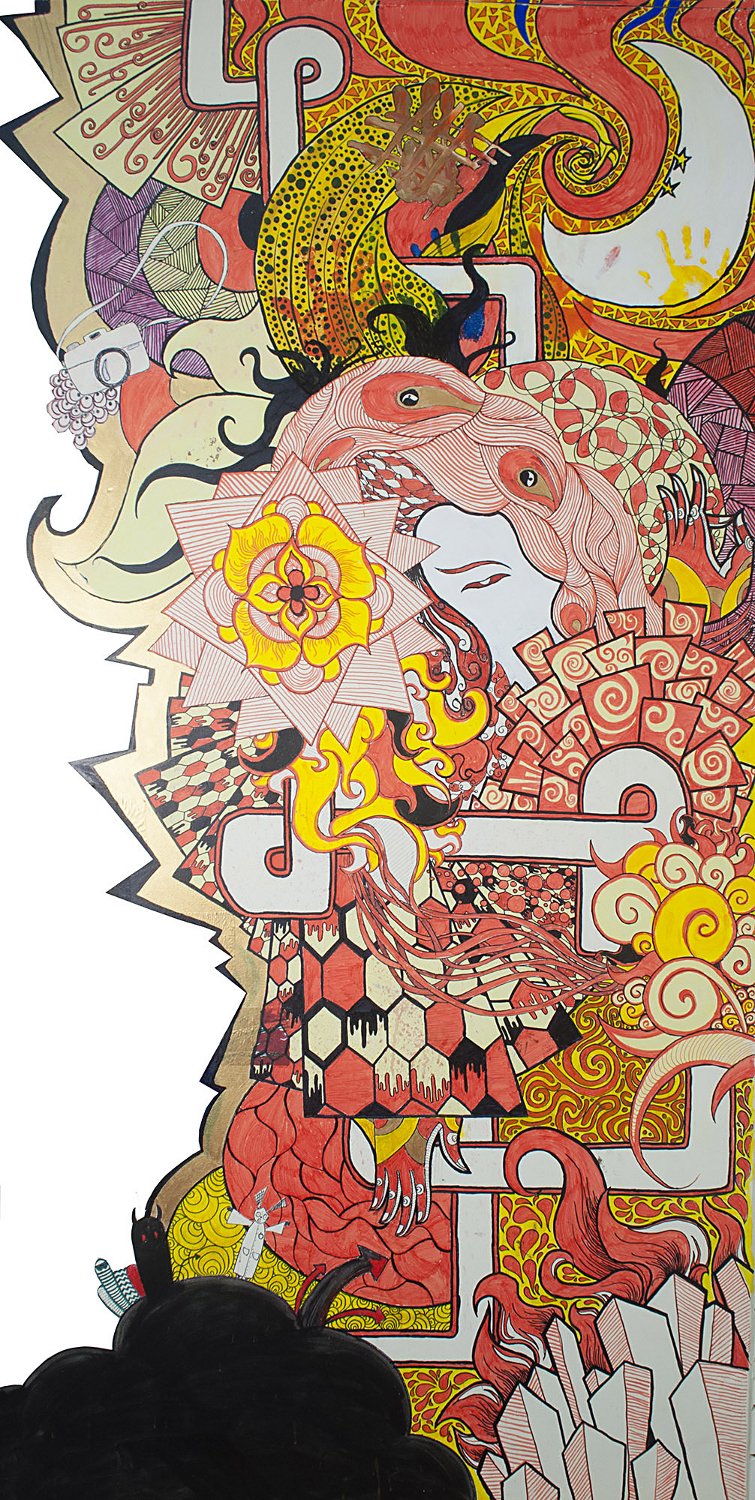

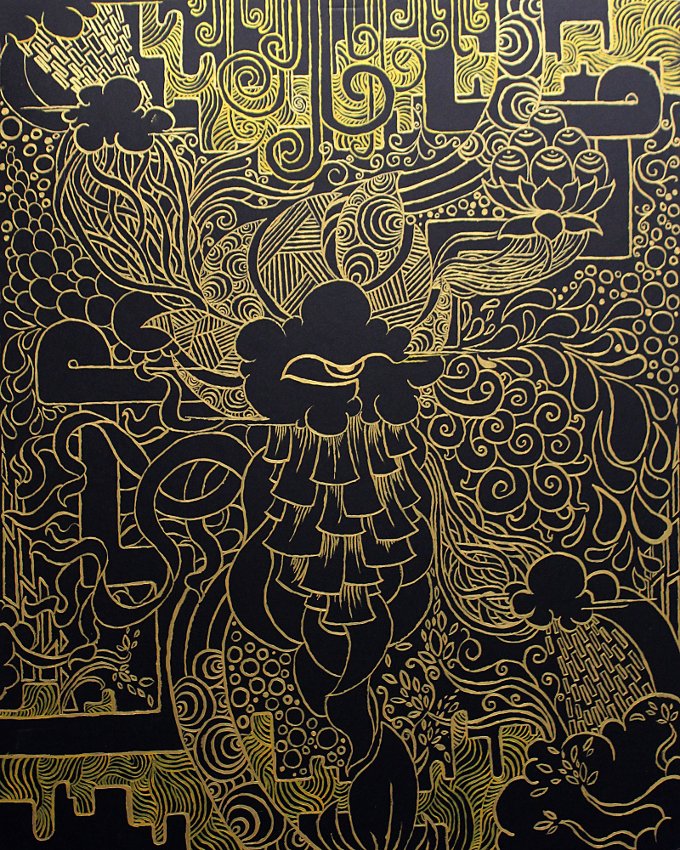

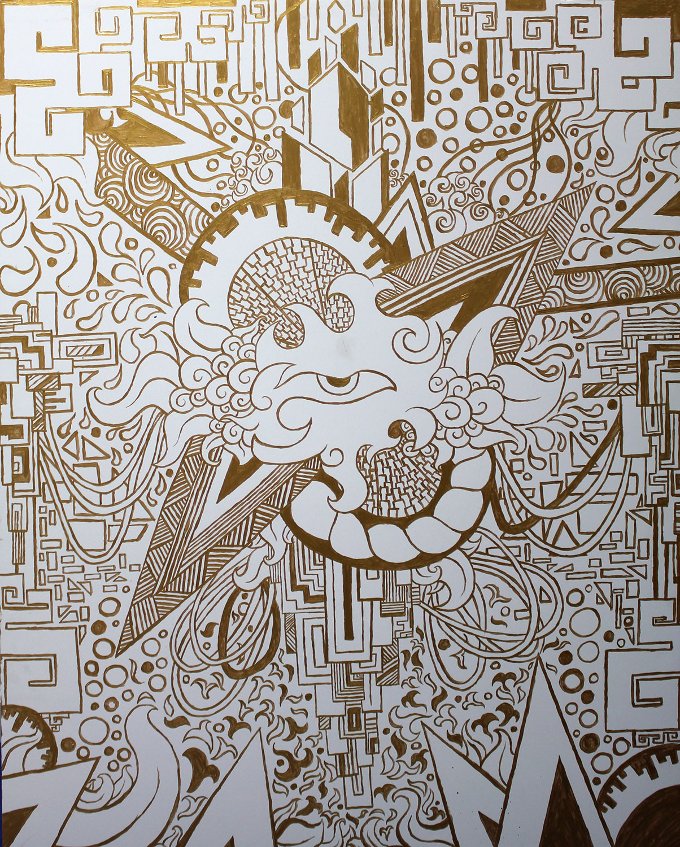

Meeting people on the Internet seems to be Kunsang Gyatso’s forte. I found the 25-year-old artist on the Tibetan Arts Collective website, whose founder, Thupten Kalsang, reached out to Gyatso upon discovering his work. The curated space features Tibetan artists from around the world. Gyatso’s paintings are colorful, large-scale abstract landscapes, drawing influences from Rothko, de Kooning, Buddhist thangka art and Brooklyn artist Jason Sho Greene. We met at Himalayan Yak, a popular Jackson Heights restaurant for traditional Tibetan and Nepali fare. Over cups of chai, Gaytso spoke about Tibetan identities borne outside of the pervasive Tibetan-in-exile narrative. Gyatso’s own ethnic group, the Yolmo, is a Tibetan ethnic minority that emigrated from Nepal in the 1800s.

Gyatso’s work is a vivid abstraction of his deeply spiritual upbringing. As a young man, he lived in the mountains on the outskirts of Kathmandu for a year, reading Buddhist meditation and philosophy. At 19, he was the youngest student retreating there, much closer in age to many of the monks who had self-immolated in protest to the Chinese government. Eventually, two years later, he followed his family to Queens, after his father, a traditional Buddhist artist, made his move to the U.S.

Where does your work stand in relationship to traditional Tibetan art forms and contemporary art?

I haven’t really learned traditional Tibetan art formally, but since my dad was working with that, I’ve gone into his books, asked for his instruction. He does traditional art for Tashi Choling, a Buddhist center based in Oregon. But for me, it was more of a casual learning experience. Back in Nepal, I was studying business, economics–it was for a lack of a good art school…But after I came here, I saw the possibility, in a way. I went to Laguardia Community College. At first, I thought I would study graphic design. It was actually in between studying, I [got into] photography, black and white photography, and that was when working in the darkroom–something in the process—my perspective changed a bit. I wanted to paint, make drawings. And not just for a commercial purpose.

One hundred and twenty-one self-immolations of young Tibetan monks have occurred since 2009. Do these tragic political protests make their way into your work?

My work tends to be more personal rather than reflecting the social situation. All these happenings, it does influence me. I do respect their act [of self-immolating], in a way. But it’s something that should not have happened. It’s hard to say, [if] these things really translate into my works, but they have a subtle effect. I see creating political work as a possibility, but at the moment I have other ideas that I’m working on…But actually, now that I’m thinking about it…I did this one painting, when about 20 people had self-immolated, at that time. This piece is called Om in Desperation. Om is pretty universal, considered the formal sound humans produce. Here the figures are dripping away, escaping. I was going through the news. All these immolations were taking place in Tibet, but this one time, this guy immolated himself in Boudha (in Nepal). I grew up there. It got to me.

Have you collaborated with artists from Tibet or Nepal?

In 2011, I met artists from Nepal and Tibet. We started this art group called “Project Art,” and we did our first exhibition at Space Womb.

That was the first time within our community here, that there was an art exhibition. I’m not with the group anymore. There was conflict…too many members. A series of mine, “Beyond Bodies,” explored the Buddhist concept of non-attachment. The first exhibition helped an NGO called Adhikaar. It’s for Nepali women, but there’s involvement of Tibetans too.

What are you working on at the moment? Any shows coming up?

One series is based on my mom; she’s really loud. She uses a lot of curse words. There are these words in my native language. Nongyo–broken. Bindu–trash. Thungna, is a rag you use to wipe shit. It’s interesting, it’s hard to translate to English and make it sound [that] bad. I’m also taking black and white photographs and drawing over them. Personal photographs of myself. Colors I get from traditional thangka paintings. Very vibrant, orange, green. I’m working on a series based on the Buddhist rosaries–they have 108 beads. It connects to three concepts. 1 is everything, 0 is emptiness, 8 is like the mathematical symbol for eternity. I have a show in Delhi in 2014, through Thupten (founder of Tibetan Art Collective).

How do you think people born in Tibet view Yolmos? Do people assume you’re born and raised in Tibet?

I speak fluent Tibetan. Most people think I’m Tibetan. I’m not really Tibetan, it’s always a process of explaining. Tibetans see [Yolmos] as very religious, that’s what I’ve heard at least. Both my parents are really religious. Yolmo people are basically residents of Nepal. Over time, they began to identify themselves more as Nepali citizens. If you were to ask–Tibetan people see Yolmo people more as Nepali citizens, when it comes to political terms. Yolmo people, as a group, are not really connected to the political situation there. My connection with Tibetan people has been stronger. A lot of my friends are Tibetans [living-in-exile]. It’s because I went to a Tibetan school in Nepal, all through nursery to the 10th grade. As pure Tibetans, they seem to have a more direct connection to whatever their cause is and everything. But in my case, I would be there thinking, I don’t have the genuine drive in a way. I was supporting the cause, but at the same time, I saw myself differently.

How do you relate to the different Tibetan and Nepali communities here?

I’m exposed to so many spaces in Queens, Sunnyside, Jackson Heights, Long Island City. Around here [in Jackson Heights] people are more traditional. Say someone dies in Nepal, they still gather here, say offerings. There are dharma centers around here, I’m not sure where they are, but they’re around. [laughs] I’m still in touch, adhering to the cultural values. Everything goes back to the Buddhist philosophy. I try to apply to my everyday life. Simple acts of generosity. Always looking at people with a positive mind, not with doubt. One of the things I see in NY, people are always doubtful of other strangers. I don’t have expectations about how my work should stand in community. Everyone knows that Tibet is taken over by China—everyone just throws Tibetans into that. They’re almost stuck in that mentality in a way. [But] in other ways, there’s a culture that’s growing. Like living in India, or in exile. There’s this concept of Tibet that most Westerners have–oh, it’s this land of peace, religious Buddhist people, but beyond that, there’s the actual living of Tibetans outside of Tibet. They’re not constantly praying 24/7.