John Okada deserves credit for framing his book around the character of a resister—but he missed the opportunity to portray the depth and breadth of principled protest by incarcerated Japanese Americans.

November 20, 2019

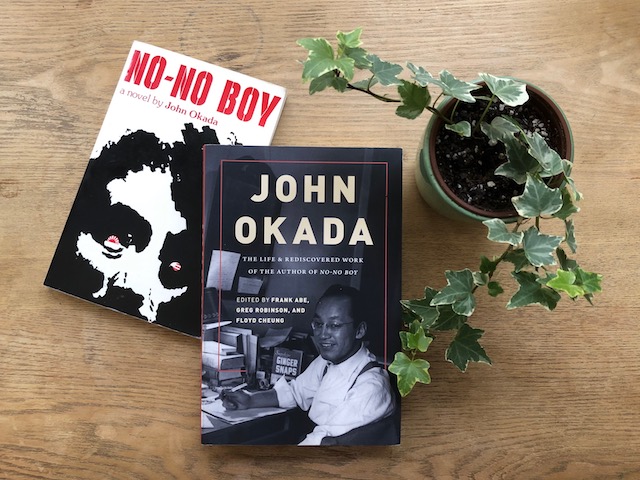

Editor’s note: This is one of several essays on The Margins exploring the legacy of John Okada’s 1957 novel No-No Boy. Read the others here.

Few works of fiction portray the Japanese Americans who protested World War II. For that reason, readers can be forgiven for assuming that the protagonist of John Okada’s No-No Boy, Ichiro Yamada, is representative of all Nisei resisters. He is not, and this presents a problem in reading the book within the context of a history that is far more nuanced.

I want to examine the differences between several different types of protest against the wartime concentration camps, and to show how one book regrettably reinforced several persistent myths about Japanese American resistance to incarceration: that those who protested were disloyal to the United States; that those who protested made the wrong decision for themselves and their families; and that those who protested were motivated by self-hatred.

In his novel, John Okada knowingly or unknowingly confused two distinct types of Nisei resistance. Ichiro, in the novel, is pejoratively called a “no-no boy,” and the author gave this epithet to the title of his book. This form of resistance emerged in 1943, when the U.S. Army and War Relocation Authority undertook a mismanaged registration process for Japanese Americans. In response to two contentious questions—designed to assure the public that the Army would only accept volunteers who were certified as loyal to the United States—12,000 men and women answered “no.” (For women, the question was adapted for service in the Women’s Auxiliary Corps.) This questionnaire was also used to clear those in the general camp population for release from camp if they had outside sponsors at a college or job.

Among the Nisei, anxieties arose over whether answering “yes” to question 27, which asked about willingness to serve in the armed forces of the United States, meant a person was automatically volunteering for the army. Also problematic was question 28, which asked a compound question of swearing allegiance to the United States and forswearing allegiance to the Japanese emperor: a “yes” implied that the respondent had once sworn an allegiance to the emperor of Japan that they never had. For those who answered “no” to these poorly-written questions, the unintended consequence was to create, on paper, a class of so-called “disloyals” who could then be easily segregated from the rest. They were shipped off to the Tule Lake Segregation Center. The Japanese American community itself bought into the notion that these men and women were “disloyal” and came to refer disdainfully to segregees as “no-nos.”

But a second form of mass protest emerged a year later, in January 1944, when the army reinstituted the draft for the Nisei in camps. These young draft resisters had answered “yes-yes” to the loyalty questionnaire (those who qualified their answers received individual hearings) and were therefore deemed “loyal”; however, they refused to report for induction while imprisoned in a concentration camp until their rights were first restored and their families released from camp. In all, 315 were convicted of violating the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940 and sentenced to an average of three years in a federal penitentiary, alongside people with serious criminal convictions. They were pardoned by President Truman on December 23, 1947.

These two types of protesters, draft resisters and “no-nos,” were not one and the same. As depicted in Okada’s novel, Ichiro is clearly a draft resister who served two years in a federal penitentiary, yet throughout the story he is described as the “no-no boy” from which the book takes its name.

◻︎◻︎◻︎

When I first read No-No Boy, I was disappointed to discover that it fails to capture the motives driving real-life resisters. Frank Emi was a leader of the organized draft resistance by the Fair Play Committee at the camp at Heart Mountain; Jim Akutsu and Frank Yamasaki were friends of Okada’s from Seattle who resisted the draft at Minidoka. All three were troubled by Ichiro’s inability to articulate the American patriotism that lay at the heart of the real resistance. Emi was unable to relate to the character of Ichiro and suspected the author of a pro-military bias, as Okada had volunteered for the Military Intelligence Service:

He’s a good writer, pretty verbose, but he writes about Ichiro from his standpoint as a veteran. And he must have a very anti-resister feeling to portray Ichiro as a whining, self-pitying, weak-kneed person. The resisters that I know are very firm in their belief that they did what was right and they don’t take any guff that he had to take. Especially that portion where his so-called friend at first got to the point where he started spitting on him. I think any of our resisters would have probably hauled off and smacked him.

With renewed interest in the novel, Jim Akutsu welcomed the opportunity to tell his own story, but he resented the suggestion that he was the source for Ichiro. Okada “writes of me not as a strong person but as a weakling,” Akutsu complained. Yamasaki also rejected the portrayal of Ichiro; he saw the character’s lack of self-esteem as a reflection of Okada’s own. Bill Nishimura, a “no-no” who was a former prisoner of the Colorado River WRA camp (commonly referred to as Poston), the Tule Lake Segregation Center, and the Santa Fe and Crystal City Department of Justice camps, never wanted to read the book. Heart Mountain resister Yosh Kuromiya at first had the same reaction, but changed his mind.

I was puzzled to discover that Frank Chin, Lawson Inada, et al. regarded John Okada as an outstanding Nisei writer, so I read and re-read No-No Boy several times in the hope of discovering what I had missed. I still haven’t grasped the real message of the book. Nonetheless, I now regard John Okada as an extraordinary pioneer of Asian American literature.

◻︎◻︎◻︎

Ichiro’s life was entwined with that of his immigrant mother, who clung to the kachigumi (winning group) belief that demanded continued loyalty to the emperor, despite word of Japan’s surrender. It is only natural for an immigrant to retain love of one’s native country, especially if the new host country bars them from naturalized citizenship—and it was easy for the government to denounce Japanese American protest as a pro-Japan element disloyal to the United States.

Japanese American protesters were ostracized and misunderstood even by their fellow Nisei. The Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), the only national leadership for the Nisei, waived the right of Nisei to protest their evictions, collaborated with the government during the incarceration, and urged the segregation of what it called “troublemakers.”

In reality, the loyalty advocated by the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee (FPC) was loyalty toward the United States Constitution, not to the government or to white acceptance. The FPC took up the American tradition of civil disobedience, a point explicitly stated in the FPC’s manifestos:

Without any hearings, without due process of law as guaranteed by the Constitution and Bill of Rights, without any charges filed against us, without any evidence of wrongdoing on our part, one hundred and ten thousand innocent people were kicked out of their homes, literally uprooted from where they have lived for the greater part of their life, and herded like dangerous criminals into concentration camps with barbed wire fences and military police guarding it, AND WHEN WITHOUT RECTIFICATION OF THE INJUSTICES COMMITTED AGAINST US NOR WITHOUT RESTORATION OF OUR RIGHTS AS GUARANTEED BY THE CONSTITUTION, WE ARE ORDERED TO JOIN THE ARMY THRU DISCRIMINATORY PROCEDURES INTO A SEGREGATED COMBAT UNIT! Is that the American way? NO!

By contrast, the valor of the Nisei soldiers inducted from the camps addressed none of the constitutional issues raised by the mass incarceration. What their record accomplished was to restore the public’s faith in the loyalty of Japanese Americans, and serve the public relations campaign by the government and JACL to win racial acceptance for the Nisei after the war. JACL national director Mike Masaoka exhorted the Nisei to prove their loyalty by being “ready and willing to die” in a “baptism of blood,” a self-sacrifice that had less in common with constitutional principles than with the fervor of samurai in Japan who carried out the orders of their lord without question, even unto death.

◻︎◻︎◻︎

Okada touches upon a third form of mass protest in the story of Mike, a character who angrily renounced his U.S. citizenship and applied for expatriation to Japan. The government conveniently enabled this action in 1944 by passing the Denaturalization Act, allowing citizens to renounce their birthright in time of war, followed by Proclamation 2655, enabling the government to deport such renunciants as enemy aliens. Between December 1944 and April 1946, the U.S. Attorney General approved 5,589 requests for renunciation, nearly all of them from segregees at Tule Lake. However, when interrogated by the government during the war or interviewed by historians and journalists afterward, most of those who renounced indicated they did so not out of loyalty to Japan, but under the duress of an unjust incarceration. This was their protest against a government that had evicted them from their homes, placed them in concentration camps, then demanded that they or their sons or brothers or husbands potentially sacrifice their lives fighting in a segregated U.S. Army unit. The demoralized renunciants resented the fact that their allegiance to the government had not been returned.

This idea of the “reciprocal obligation of allegiance” was raised in a class-action lawsuit, McGrath v. Abo. An appellate judge, William Denman, restored the citizenship of many who had been deported, and wrote: “Absent protection, allegiance is no longer obligatory. Absent protection, allegiance becomes, again, a matter of choice.” Absent protection, the Tuleans exercised their freedom to choose whether or not to remain citizens of the United States. Tadayasu Abo’s attorney, Wayne Collins, told his client that despite the scorn from others, he needn’t feel ashamed of renouncing his citizenship: “You did so because the government took advantage of you while it held you in duress and deprived you of practically all the rights of citizenship.” As law professor Patrick Gudridge puts it, “In renouncing citizenship, they proclaimed themselves constitutionally quintessentially ‘American.’”

All of these perspectives contrast sharply with the novel’s portrayal of Ichiro. Okada’s characters seem to struggle with being of Japanese descent, a message summed up by Kenji, the veteran: “Go someplace where there isn’t another Jap within a thousand miles. Marry a white girl or a Negro or an Italian or even a Chinese. Anything but a Japanese.” Okada peppers Ichiro’s dialogue with such phrases as “we made a mistake” or “there is no retribution for one who is guilty of treason.” Freddie, another draft resister, says, “You and me, we picked the wrong side.” Readers may well conclude—erroneously, in my opinion—that it was a mistake for Japanese Americans to protest during the war. I argue that if we look at other critics of Okada’s book, and of the time period, readers will not reach this conclusion. Stephen Sumida is an example of one such critic. In his piece in John Okada: The Life and Rediscovered Work of the Author of No-No Boy, Sumida says, “The novel began with Eto, posing as a war veteran, spitting on Ichiro the no-no boy. The novel ends with Ichiro comforting the distraught war veteran Bull. This trajectory, I believe, is the arc of the story and a measure of the inches or miles Ichiro has traveled on Japanese America’s and America’s road of ‘Rehabilitation.'” What Sumida is pointing out is that Japanese America and America, as a whole, cannot begin the healing process unless draft resisters and veterans acknowledge and accept one another’s experiences. Okada may well have wanted to symbolically show that the actions of the soldiers in battle were no more important than the draft resisters’ fight in the courtroom.

I believe that John Okada deserves credit for framing his book around the character of a resister, but he missed the opportunity to portray the depth and breadth of principled protest in the camp. By reinforcing the false constructions of loyalty continually created by the government through waves of eviction, segregation, Selective Service, and the push to expatriate the prisoners, the novel contributes to popular misconceptions about Japanese American resistance inside the camps, thus inadvertently doing the real resisters a great disservice.

We have to remember that not all Japanese Americans lost their sense of ethnic pride. After the war, many protesters took occupations in farming or gardening that enabled them to be their own boss. The Gardena Valley Gardeners Association, which counted many former Tuleans among its eight hundred members, promoted Japanese language and culture through an annual show, beautification programs to create traditional Japanese gardens throughout Southern California, and regular maintenance landscaping at Buddhist temples, Japanese language schools, community centers, and elder care facilities. Others used their bilingual fluency to act as bridges with then-fledgling Japanese companies such as Honda, Toyota, and Sony that wanted to do business in the United States. Unlike the self-hating characters in Okada’s fictional world, these people did not suppress their “Japaneseness.” They embraced it.

A version of this essay first appeared as “False Constructions of Loyalty: The Real Resistance Against Incarceration” by Martha Nakagawa in John Okada: The Life and Rediscovered Work of the Author of No-No Boy, eds. Abe, Frank, Greg Robinson, and Floyd Cheung, p. 277-283. © 2018. Reprinted with permission of the University of Washington Press.