In 2019, No-No Boy is bigger than it’s ever been. But the book that was saved was always haunted by the books that were lost.

November 18, 2019

Editor’s note: This week on The Margins we are publishing several essays exploring the legacy of John Okada’s 1957 novel No-No Boy. Look out for the others in the coming days.

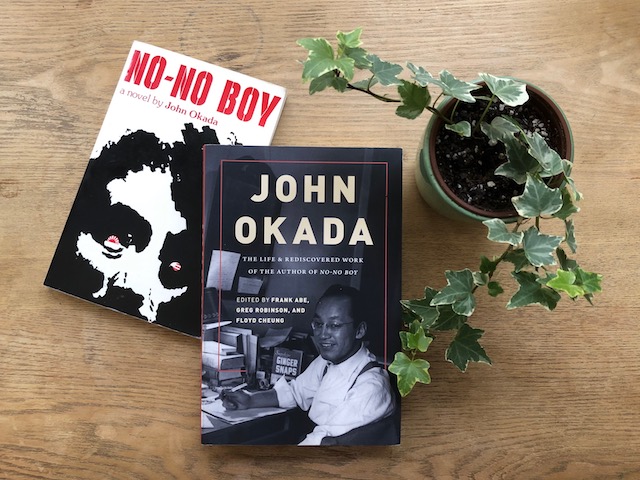

Once upon a time, in the poet Lawson Inada’s telling, it was simply “the book.” Published in 1957, John Okada’s No-No Boy had been largely forgotten when Jeffery Chan ran across it in a J-Town bookstore in 1970. It passed, hand-to-hand, within a scruffy group of aspiring Asian American literati that included Frank Chin, Shawn Wong, and Inada. Unable to interest publishers in a reprint, they reissued the novel themselves in 1976, as the Combined Asian American Resources Project (CARP).

At that point, it became their book, a novel that shaped and was shaped by the CARP mythos, whose sales established proof-of-concept for the republication of other works. Working with Wong, the University of Washington (UW) Press developed a deep catalog of lost classics, taking over the Okada reprint in 1979 and keeping faith with Asian American literature ever since.

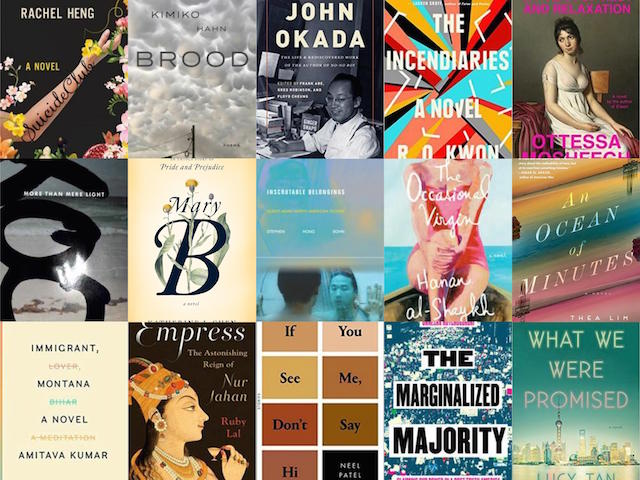

Now, a new chapter has opened in the novel’s long and eventful afterlife. Last year, UW Press published John Okada: The Life & Rediscovered Work of the Author of No-No Boy, edited by Frank Abe, Greg Robinson, and Floyd Cheung—a collection that both reaffirms CARP’s mission of literary recovery and frees Okada to stand on his own historical terms. This spring, Penguin Classics published a controversial competing edition of No-No Boy, which was later withdrawn from distribution in the US. The UW Press edition remains a top seller. In 2019, No-No Boy is bigger than it’s ever been.

But the book that was saved was always haunted by the book that was lost.

◻︎◻︎◻︎

In The Grey Album: On the Blackness of Blackness, the poet, critic, and archivist Kevin Young writes eloquently about the idea of a shadow book—a book that you know of but that doesn’t actually exist, whether because it’s no longer extant, or never came to fruition, or is merely a figment of the imagination of another text.

Young is concerned specifically with black aesthetic traditions, but the idea of a shadow book resonates with Asian American literature, and with any literature produced under conditions of social subordination. The history of Asian American literature is inexorably, inexorcisably haunted by what could have been—a library of shadow books.

In the case of John Okada, I can identify at least three.

For Frank Chin and his CARP co-conspirators, the shadow book was Okada’s second novel, and the tale of its loss lent force to the critical mythologies they constructed to help conjure an audience for Asian American literature. They went searching for the author in 1971, but missed him by a matter of months. Dorothy Okada, John’s wife, explained that he’d died, and she’d moved into an apartment and gotten rid of all his effects.

Among the items now lost were papers, childhood photos, and all the drafts, notes, and materials he’d accumulated in years of work on a second novel. Where No-No Boy considered the defining experience of the second-generation Nisei—the dilemma of compulsory loyalty in the teeth of World War II incarceration—John’s second novel was to center on their parents, the Issei. Dorothy had assisted him in his research. The young writers couldn’t believe it was gone.

In a famous 1976 essay, appended to CARP’s reprint of No-No Boy, Frank Chin narrates his reaction as a gratuitous fantasy of gendered violence. I wanted to kick her ass around the block, he wrote. In person, he was respectful, and CARP took care to copyright their edition of No-No Boy in her name. Over the years, Chin’s retellings focused on another detail. Dorothy told him that UCLA had turned down John’s papers, a story he spun into an indictment of his old nemeses, the Japanese American Citizens League and Asian American studies programs. In the new collection, Frank Abe politely corrects him—Dorothy had contacted an unrelated department at UCLA—but for Chin, the tale of the lost novel was always just a parable about how Asian America neglects its writers.

But what did it mean to Dorothy?

For those familiar with Japanese American history, her decision to dispose of her husband’s effects evokes a recurring scene in literary and historical narratives of the war. Set in the period of terror between Pearl Harbor and camp—that season of family separation, when the FBI began rounding up Issei community leaders—the scene is generally told from the perspective of Nisei children. As they watch, their parents burn or bury family heirlooms, papers and printed material in Japanese, records, toys, and any objects that government agents might deem suspiciously foreign.

These stories are often interpreted as allegories of cultural heritage, with the narrative itself offered in the place of irredeemable loss. But imagined from the Issei vantage, the meaning shifts. The destruction of what is most precious can be understood as an act of commemoration against all hope, consecrating to memory what is placed beyond the reach of the living.

A Kibei from Hawai‘i, Dorothy Okada presumably wouldn’t have direct experience of such a scene, but her account of her decision to Chin glosses it succinctly: I thought, well, I have him in my heart and I have him in my head, what more evidence do I need? Read within a collective history, her act may appear either as a traumatic repetition of the scene, decades later, or as what Tamiko Nimura, reflecting on Marie Kondo, identifies as “a form of release” from Japanese American hoarding practices that express “intergenerational trauma.”

In the end, barring some miraculous reemergence from an unknown archive, the shadow book of the Issei remains lost, sealed in the space between Dorothy and John. It is not merely a tale of immigrant striving, or of the gap between a generation defined as aliens ineligible to citizenship and their US-born children, upon whose tenuous claims to the rights of citizenship their own fate depended. It also bears the tale of a marriage, of all the gendered ambitions and disappointments that could or couldn’t be contained within that economic and legal and social form, and of whatever possibilities of love or friendship that might rationalize or escape it.

However you might read this shadow book, it asks you to consider Dorothy, not as a villain or victim or fool, but as a protagonist in her own right.

◻︎◻︎◻︎

Months before the release of No-No Boy in 1957, a 33-year-old John Okada revised his résumé. Married with children, he’d only recently left a career as a librarian for the defense industry, and in an accompanying personal statement, he assured prospective employers that his forthcoming novel represented a mere avocation—no obstacle to a heavy workload.

In his own words, Okada sought to seal the figure of the novelist within an impenetrable archetype of the 1950s family man: devoted husband, proud father, workaholic breadwinner. Perhaps, he mused in the personal statement, I have been endowed with a larger capacity for normalcy than most people.

Quiet as it’s kept, that’s a paradox. To have an abnormal capacity for normalcy seems logically impossible, until you realize that John Okada posits “normalcy” as performance, an anxious disavowal of the drama and strangeness that defines a life, or a marriage. His phrasing, unnecessarily elegant for a business letter, presumes you already know this, while steering your attention away from that insight’s consequences.

It’s also a characteristically Nisei thing to say, if you can learn how to read it.

It doesn’t require too much imagination to recognize this self-portrait as haunted. And because any story about a shadow book is necessarily the story of a haunting, of a mysterious agency that has eluded capture in print, tracing this haunting may lead you to a second shadow book, distinct from Okada’s Issei novel.

This shadow book, fictional and fictionalized, shares its title and subject with Abe, Robinson, and Cheung’s John Okada. The author’s own biography suggests the makings of a novel that would realize his literary ambitions, while exceeding the scope of his extant works. It’s the Great (Japanese) American Novel Okada might have written: the story of a representative Nisei turned midcentury Everyman.

There’s John Okada, back from the war, a young veteran taking creative writing classes at the University of Washington, and heading to Manhattan for an MA in English from Teachers College. There he is, married, paying the bills as a librarian in sleepy Seattle and booming Detroit, and jumping careers to become a technical writer for Chrysler Missile and Hughes Aircraft, and an advertising copywriter in sunny LA.

He works too hard and smokes too much, sure, but look: he’s got a house in the suburbs and two kids in college, and the dream people talk about, who’s going to say he hasn’t made it? The war is just a distant memory. He’s forty-seven years old. Then one day his heart gives out.

He went in the house to do his taxes and he died.

All the clocks in the house stopped, Dorothy said, even his wristwatch.

The rambling itinerary of Okada’s postwar biography animates the great themes of midcentury American life, like some lost novel about an earnest striver, adrift in the military-industrial complex and Mad Men-era ad agencies. This is the shadow book of American empire, recast with a Nisei hero.

How could this be? After everything that happened to Okada and other Japanese Americans during the war, who could have imagined a sequel like this?

◻︎◻︎◻︎

To understand John Okada’s postwar life, you need to understand the peculiar history of Japanese American rehabilitation, which begins earlier than you might think.

In this story, the wartime experience is broken in two. The first phase—from the FBI roundups to the forced removal of all citizens of Japanese ancestry, alien and non-alien to temporary detention facilities—continued a prewar history of Asiatic exclusion. But the second phase pioneered a logic of racial liberalism, of benevolent intentions and innocent power, which would dominate the postwar era. This phase was established by the War Relocation Authority (WRA), which oversaw the permanent camps and sought to rehabilitate the incarcerated, sifting disloyal no-nos from salvageable citizens.

The model subject of rehabilitation was either a student or a soldier, and Okada was both. After only three weeks at Minidoka, Okada left for Nebraska’s Scottsbluff Junior College, one of the first participants in a student resettlement program. Next, he volunteered for the Military Intelligence Service, flying twenty-four missions out of Guam, before continuing his service in postwar Occupied Japan.

In this story, it is rehabilitation, rather than forced removal, that defines Japanese American incarceration. Arguably more traumatic and consequential, its endpoint is forever in question. Was rehabilitation achieved by the Ex parte Endo Supreme Court decision, and the closing of the camps? Truman’s 1946 White House ceremony honoring of the sacrifices of Nisei soldiers? The New York Times’ proclamation of model-minority success in 1966? The passage of redress under Reagan in 1988? There is no conclusion, because this rehabilitation continually reenacts a testing of loyalty to prove birthright citizenship—the very process it purports to end.

Recall that the name by which the US government summoned Japanese American citizens, the non-alien, is a euphemism, a fudge, and a paradox. It’s a variety of the category it negates—the non-alien, if it exists, is a type of alien. Like the construction “no-no boy,” it’s a double negative—not-not a citizen. More precisely, the non-alien is a citizen whose rights are cancellable on racial grounds.

The instability of this figure was more than the law or the nation could bear to perceive, and so a substitute was needed, the Japanese American (no and no, again). The rehabilitation of the Japanese American, which is ongoing, establishes loyalty and innocence—beyond the shadow of a doubt—as the conditions of citizenship and the vindication of rights. In so doing, it disavows the non-alien, whose punishment was never predicated on guilt or proof, but on doubt. To rehabilitate the Japanese American is to deny that the non-alien ever existed, restoring national innocence by disappearing the conditions of the crime.

These days, the non-alien is everywhere and nowhere, the threat that must be contained at the border and the terror of vulnerability that makes you comply, but anywhere its existence is not denied, it is denied the ability to speak. Its liberation would require nothing less than the abolition of citizenship.

The non-alien haunts all the shadow books of Japanese American life and letters, including the lost novel on the Issei that Dorothy Okada disposed of, and the unwritten novel of John Okada’s own life.

But there is one more shadow book to consider. Like a cartoon depiction of vision disoriented by a blow to the head, it appears in the oscillation between the other two, never quite resolving itself. This third shadow book is narrated and authored by the non-alien—a position from which one cannot speak—and it is unrepresentable.

Its title is No-No Boy, and the task you are given now is to learn how to read it.