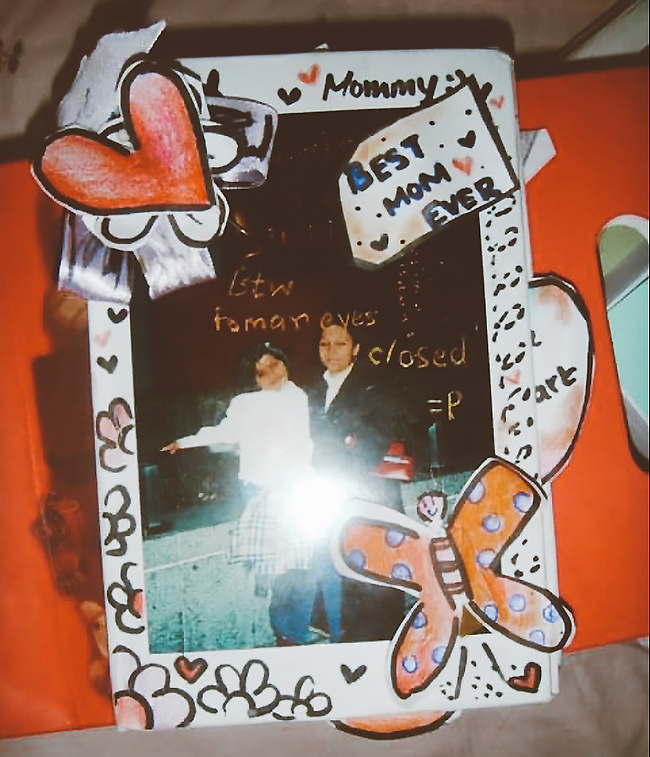

Women like my mother don’t post their lives online. Often, their stories remain untold and undocumented.

August 26, 2021

to my dear ma

to my dear ma

“After my divorce, I stopped buying groceries during the day. I would try to go when there were no people around, it became a quest to see how quickly I could get my items from the store and come back without making eye contact with anyone. I didn’t want to give someone the chance to recognize me or try to chat.” My mother, Sume, recalls.

The world, as we know, has not been kind to women. Especially immigrant women and independent women. And as I reflect on my mom’s life so far, it is not lost on me that such is the reality (or far worse) for many women that come to America in pursuit of a better life, not for themselves, but for their husbands and children.

Ironically, I was happy when my parents got divorced. I remember them coming back from the lawyer’s office; they barely said a word. There was a strange lull in the house but for the first time in months, the house was quiet. It meant I no longer had to stay up long nights to hear them quarrel. I no longer had to bear witness to the crying, the negotiating, the whispering and the hysterical yelling. I almost felt free. Of course, I did not realize at the moment the impact it would have on the next few years of my life. Or theirs.

Just three years ago, my mom and I had left Bangladesh to move into my dad’s neatly drawn one-bedroom apartment in Jackson Heights, NY. I remember my mom finding an empty row of seats in the back of the plane and there I slept, in the ungodly reddish glow of Aisle 33. Something about my mother’s lap comforted me; she squeezed my shoulder gently. I always wondered what she was thinking, I wondered if she knew.

Finally, a few days ago, I asked her what was going on in her mind at the time and there was a flash of distant sadness on her face. “I was both excited and sad. It wasn’t about the American dream for me—it was the chance to live in the same house as my husband after six years of living apart from each other. But a part of me was sad because I knew he had already given up.”

Women like my mother don’t post their lives online: they live offline, they eat offline, they struggle offline. Often, their stories remain untold and undocumented. Most immigrant women leave their home countries in search of a better life for their husbands and children, not for themselves. They give up all that is familiar to come to a foreign land and befriend their husbands’ friends’ wives and live their husband-orchestrated lives.

While there are people only now talking about how hard South Asian immigrant men have it, we fail to mention the magic workers behind the scenes who each have their own unique story. We further fail to mention the women who leave their husbands and try to navigate their way around our communities. But if we continue to dismiss the stories of these individuals who keep the traditional household together and serve as the connective tissue between most fathers and their children—we will continue to teach the incoming generation of immigrant women that this is the status quo. That a woman’s role in society, especially as seen in immigrant households, is to live only for others and not for themselves.

to my strong ma

to my brave ma

One night at dinner, my mom revealed her life in Bangladesh was not particularly joyous. In fact, the combination of losing her mother as an infant and growing up with a less-than-affectionate stepmother always made her yearn for a different life. She dreamt of falling in love with the man she’d call her husband and share laughs over a cup of cha. Fast forward a few years, she began to understand that would not be her reality. She moved to New York at the age of 25 for her husband but little did she know that in three years, she’d be alone.

The school moms would watch her race me to P.S.69 every morning, with my backpack in one hand and my lunch in the other. I still remember glancing up at her from my donut and seeing the furrowed brows on my mother’s beautiful face and wind in her hair. She’d often keep to herself and only talk to the other moms if they approached her. It was not because she thought she was better than them, little did they know she was too occupied trying to save her marriage and not letting the world know in the process. The same women later would say, “That woman always put up such an act, like she was such a good mother, running her daughter to school every morning. If she was such a good mother, why would her husband leave her?”

In a New York Times article, Priyanka Upadhyaya, a licensed clinical psychologist and clinical instructor at the Department of Psychiatry at NYU Langone Health, indicated that many South Asian women live separate lives from their partners, but choose not to legally divorce, as there are many advantages to staying married—social, emotional, and economic. Upadhyaya has counseled South Asian American clients who, because of their divorces, now receive far fewer social invitations or, worse, have been shunned by family members or risk a shrinking of their professional networks. My mother took the risk.

Women unfairly bear the brunt of divorces in the South Asian community. For whatever reason my parents’ marriage fell apart, I am glad they have both found their separate ways in life. However, the community does not seem to have moved on. There were of course some supportive friends that had come forward and helped my mom after my dad and I moved back to Bangladesh.

But for most of society, they were more preoccupied with why this woman became husbandless than to think of giving her support. Our minds are consumed by the “oohs” and the “ahs” of the situation rather than thinking of ways to aid those in need financially or emotionally. It affects the children too. I remember one middle school teacher in Bangladesh saying to another, “Aaisha is a child of divorce, she comes from a broken family. Can’t blame kids these days, they don’t get real guidance.” It was not the first time I heard someone reduce my existence to the subject of some aunty’s gossip but I still burst into tears hearing it come from a teacher, for no other reason than knowing my parents are the best parents in this world. They just were not good at their relationship.

to my resilient ma

to my beautiful ma

Within a week of my departure to Bangladesh, my mom decided it was too hard to live in the same place and booked a one-way flight to California. And there over the next few months, she was diagnosed with depression. She looks at me with subdued eyes, “I didn’t have the luxury of addressing my depression, I was overwhelmed trying to figure out where the next month’s rent was coming from.” But unable to find work in San Pedro, she returned to New York. But why return to a place where one is judged when “their husband leaves them” and every fabric of their being is questioned?

In Madhulika Khandelwal’s “Becoming American, Being Indian,” she writes that Jackson Heights fails to represent the various changes and growth that women experience when it comes down to the role played by South Asian women in American media, politics, STEM, and the business world. “This little ethnic community is a business center that often portrays women through dress, jewelry, and Bollywood posters. These forms of portrayal tend to fantasize and stereotype South Asian females, depicting them as materialistic, delicate homemakers.”

As a South Asian woman myself, my journey starts by learning about my mother’s experience as a woman in this society. In doing so, I am also beginning to understand the following: Immigrant women come to Jackson Heights and never leave Jackson Heights. Because this becomes all that they know, a home away from home. In a city with 8.4 million people, foreign currency, and a complicated transportation system—Jackson Heights becomes a solace to immigrant women. A safe haven with no concern for thick accents nor language barriers, cash-only stores, and access to their own people.

According to the 2000 Census, the top reason for choosing a particular neighborhood was to live with their own community (37.3 percent of survey respondents). My mother still shops from the same grocery store as she did when she first moved into our apartment on 71st. She buys all her electronics from the same store by Roosevelt station. She speaks the same language as the shopkeepers, as the person who files her taxes and as the man who advises her on health insurance. And when she is trying to parallel park next to Apna Bazaar on a Sunday, she knows her fellow Bangladeshi will come to her aid and guide traffic.

She tells me, “Aaisha, no matter what these people have wondered about me—I find comfort in knowing if something were to happen to me in the middle of the night, I know exactly who to call from down the block. If something happens to me on the street, I can easily communicate with passersby. I can’t imagine doing that anywhere else.”

Not only will people help her, she is also empowered to pay it forward. She gives directions to the elderly lost on their way to the mosque and shows up to campaign for Democrats. Perhaps that is why my mother chooses to stay by Jackson Heights. She chose to stay when she worked three part-time jobs in the city to put herself through a second degree. She chose to stay when she had to move apartments every year with rising rent. She chose to stay when she lived in someone’s basement and she also chose to stay with three other single women in a cramped living room. Jackson Heights, like New York, may beat you down but it will always take you in.

to my dear ma

to my dear ma

I was curious to hear how my mom was okay with making her story public, if she was ready to deal with what people around her would say. To my pleasant surprise, albeit keeping with her character, she replied “I no longer care what the world thinks about me, this life has taught me to be fearless. In fact, I want to share my story. So anyone who has gone through it or is going through it right now can know there is a future for all of us.”

Since the autumn of her divorce, my mom has gone on to live in California, Dhaka, and New York. She now holds two Bachelors’ and one Master’s degrees and has even worked three part-time jobs at one point to support herself. She has helped other South Asian women living alone, provided financial and immigration advice to neighbors and has remained my sounding board for all major decisions. She lives with my stepfather in Queens, and is at home taking care of my beautiful 5-year-old sister.

I tell her story to surface the stories of Bangladeshi women who live offline, away from the public eye: the wives of cab drivers who don’t speak English but have left their homes and everything they hold familiar for the sake of a fruitful marriage; the divorced women who share rent in a one-bedroom with four strangers; the mothers that take care of their children, cook meals for their husbands and work part-time at a Subway.

Her story is not singular but is a reflection of the unique challenges of immigrant women as they attempt to assimilate into their new communities, independent of their husbands.